Throughout history, there have been various forms of social oppression of the weak by the powerful and rich. These include, among many other forms, the exploitation of the labor of peasants by ruling elites (feudalism, serfdom), peonage, and slavery. Slavery is one of the oldest institutions in human history. For millennia, in different countries and continents, people have been enslaved. Unwritten rules of war in ancient times permitted the enslavement of prisoners of war, who were made to perform all kinds of tasks. Records from classical antiquity show that the Assyrians, Phoenicians, Hebrews, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Persians, and Chinese all utilized slave labor. In the Middle Ages, both Christians from Europe and Muslims from North Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere enslaved each other during the struggle for supremacy between the Christian and Muslim worlds. Thus, in Europe, China, Japan, and Africa, slaves made important contributions to society.

The Atlantic slave trade, the trade that linked up Africa, the Americas, and Europe, differed from ancient slavery in one fundamental respect, though—it was predicated on race.

SLAVERY IN AFRICA

The nature of slavery in Africa has been the subject of much scholarly debate. Some scholars argue that slavery as practiced in Africa differed from slavery in the Americas in that slaves were not viewed as chattel and could be absorbed into the owner’s family over time. This perspective is found in the work of Suzanne Meirs and Igor Kopytoff, who see slavery in Africa as existing along a continuum. In their view, the slave’s position in traditional African society varied from total marginality to incorporation into the society or group. R. S. Rattray, who did field research in Asante in the 1920s, also belongs to this functionalist-assimilationist school of thought.

On the other hand, scholars like Claude Meillassoux, Paul Lovejoy, and Martin Klein belong to the economic paradigm school, which sees slavery in Africa as an economic institution predicated on the outsider status of the slave. They argue that as an outsider the slave had no rights and was only considered property. As a result, the slave could in no way become part of the owner’s family, and could only live on the margins of society.

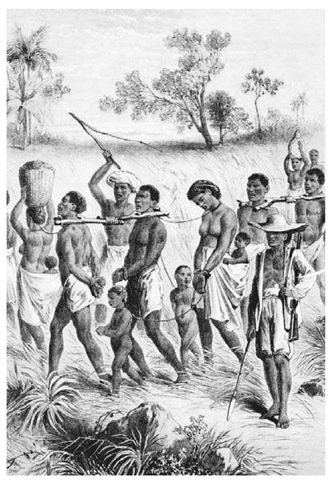

A Band of Captives Driven into Slavery. This illustration of slaves captured in Zanzibar was published in The Life and Explorations of David Livingston, LL.D. (1875)

FROM AFRICAN SLAVERY TO THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE

The gradual transformation of indigenous slavery into what became the largest intercontinental migration in history began with the trans-Saharan slave trade. The expansion of Islam into Africa led to the increased export of African slaves across the Sahara to the Mediterranean region and the Middle Eastern countries of the Persian Gulf. The wars of expansion into “infidel” territory that lasted several centuries enabled Muslim slave merchants to acquire Africans for enslavement. Some African slaves were used in the Mediterranean sugar islands, thus laying the basis for the plantation system that later developed in the Caribbean.

The number of Africans sent across the Sahara, while not as significant as the number of enslaved Africans sent across the Atlantic from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, actually increased after the era of Portuguese exploration began. What eventually led to the trans-Saharan trade petering out and the rapid growth of the Atlantic slave trade was the commercial revolution that occurred in Europe starting in the fifteenth century. This commercial revolution, which led to economic competition, was partly facilitated by a revolution in maritime technology in Europe between 1400 and 1600. Superior navigational and military technology gave Europe naval supremacy and enhanced the overseas activities and expansion of European states. Spain, Portugal, France, England, and Holland took advantage of these developments.

The Middle Passage. Sailors throw sick and dying slaves overboard during the Middle Passage, a term used to refer to the voyage of loaded slave ships across the Atlantic from Africa to the Americas.

In the fifteenth century, Europeans began to search for new sources of wealth—gold, land for sugar production, and new routes to the Far East, with its spices and silk. The Portuguese led the way and soon “discovered” the Atlantic coast of Africa. They quickly monopolized the production of sugar in the region by establishing sugar plantations worked by slave labor on the Atlantic islands of Madeira, Cape Verde, Sao Tome, and Principe.

When the Reconquista diminished the number of captives available by largely ending warfare between the Christian and Islamic worlds, the Portuguese resorted to kidnapping, raids, and purchases from African traders in order to obtain slaves for the sugar plantations. Prince Henry the Navigator made their job easier by sanctioning the import of Africans—the first party of ten was sent to Portugal in 1441 (to be Christianized and for use in mission work). In addition, Pope Nicholas V (14471455) issued a papal bull granting Alphonso V of Portugal the right to enslave non-Christians captured in “just” wars in any regions that the Portuguese might discover.

Spain sought to challenge Portuguese supremacy and thus commissioned Christopher Columbus, whose voyages of exploration led to the 1492 contact with America and the subsequent exploitation of the hemisphere’s aboriginal peoples.

SLAVERY IN THE NEW WORLD

Slaves were only imported to the New World in great numbers after other sources of labor proved inadequate. The new commercial enterprises first used forced aboriginal (“Indian”) labor, but this approach met with little success for a number of reasons. First, the aboriginal lifestyle was not adapted to systematic agriculture. Second, Indians who escaped from the plantations could easily melt into the countryside. Third, Indians were very susceptible to European diseases and died in large numbers.

The persistent need for labor also led to the use of indentured servitude. Indentured servants, largely from Europe, were given free passage to the Americas and in return, worked for plantation owners for a fixed number of years (usually seven), after which they were freed from all obligations. However, indentured servitude proved inadequate as a source of labor because the labor it provided was temporary. Also, competition for labor in Europe made the cost of indentured servants high.

The Portuguese, the Spanish, and the English soon realized the advantages of using African slaves in the New World. Africans had had a longer period of contact with Europeans, and thus did not die of European diseases at the same alarming rate as the Indians, who were encountering diseases like syphilis for the first time. As transplants from Africa, it was harder for them to successfully escape. Because the Portuguese had used Africans as slaves in their Atlantic Islands, Europeans were also already familiar with the sources of African slave labor.

THE SOURCES OF AFRICAN SLAVES

Several studies have revealed that a large number of African slaves were acquired through warfare and that indeed warfare was the major cause of enslavement. As J. E. Inikori and others have shown, the high point of the Atlantic slave trade coincided with a period during which a large quantity of guns were being imported into Africa. Many wars were initiated for the purpose of acquiring slaves, but even wars whose origin had nothing to do with the Atlantic slave trade could produce large numbers of slaves. For example, the Yoruba civil wars, though inspired by political conflicts, became the largest single source of slaves during the last decades of the trade.

A different perspective has been offered by J. D. Fage, who argues that slaving wars and raids were not the outcome of the export slave trade, and would have occurred even without the trade. According to Fage, “the motive of warfare and raiding in Africa . . . was not to secure slaves for sale and export, but to secure adequate quantities of this resource and diminish the amounts available to rivals.”

Besides warfare, other means of enslavement included raids and kidnapping. While recognized as illegal, slave-raiding parties roamed the countryside and snatched unsuspecting youth. One of the most famous enslaved Africans who was snatched in this way was Olaudah Equiano.

The judicial system was another vehicle through which people were enslaved. Some leaders exploited the judicial system by feeding people accused of heinous crimes like murder into the Atlantic slave trade.

EFFECTS OF THE TRANSATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE ON AFRICA

Scholars have long debated the impact of the transatlantic slave trade on Africa. Some, such as David Eltis, maintain that the impact of the trade on Africa was minimal; others claim the impact was profound. Different scholars focus on different aspects of the trade—including its economic impact, its political impact, its social impact, and a host of demographic issues.

THE ECONOMIC IMPACT

Among the most prominent of the scholars who argue that the slave trade led to the underdevelopment of the continent are Walter Rodney and J. E. Inikori. According to Rodney (1972), when the European slave trade removed millions of children and young adults, it robbed Africa of the most productive segment of its population. Furthermore, the slave trade and the wars it engendered created a climate of uncertainty and fear. As a result, economic development was rendered almost impossible in the areas affected by the trade. Many local industries that once existed no longer flourished. For example, many West African metallurgical and textile industries were partly ruined by the slave trade.

Rodney argues further that African industries were hurt by the type of imports that came with the slave trade. European imports into Africa did not stimulate the production process, but, rather, were items that were rapidly consumed or stored away. He adds that most of the imports were of the worst quality—cheap gunpowder, crude pots, and cheap gin. Inikori concurs, maintaining that the uncontrolled importation of cheap textiles and other manufactured goods from Europe and Asia retarded the development of manufacturing in Africa.

Henry A. Gemery and Jan S. Hogendorn (1979) conclude that the Atlantic slave trade caused not only enormous social dislocation, but also long-term economic decline in West Africa. They argue that when all costs are counted—social, political, and psychological— the welfare of West African society as a whole deteriorated markedly over the centuries of its involvement in the trade.

On the other hand, a number of scholars have argued that the economic impact of the Atlantic slave trade on Africa was minimal. Basil Davidson, for example, refutes the claim that indigenous industries collapsed. He points out that even after the trade was in place, Africans continued to weave textiles, smelt and forge metals, practice agriculture, and employ the manifold techniques of daily life.

In support of this view, A. G. Hopkins (1973) points out that as far as West Africa is concerned, no general evidence has been presented to support the claim that foreign imports led to the decline of local industries. To the contrary, he asserts that, ”many indigenous manufactures, such as cloth and pottery, remained important, and it seems likely that the market was enlarged” (p. 121). He argues further that there is no evidence that the export of labor from Africa was one of the major causes of underdevelopment. Most of the slaves taken, he claims, were peasants lacking technical or entrepreneurial skills. He does agree, however, that in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, ”when the economy began to expand very rapidly, there was undoubtedly a serious shortage of labor in West Africa, and it could be argued that at that point the pace of advance would have been faster if the slave trade had not retarded the population” (p. 122).

THE POLITICAL IMPACT

While some scholars maintain that the political impact of the slave trade on African society was minimal, most scholars now agree its impact was profound. One of the major political repercussions of the slave trade is related to the practice of exchanging firearms for slaves, which in turn led to an organization of force aimed at capturing more slaves to trade for more guns. According to some scholars, the slave trade and the importation of guns led to the expansion of militaristic states like Oyo and the subsequent devastation of the regions surrounding them. Due to this militarization, guns became important for national survival and prosperity, and because guns could only be bought with slaves, militaristic African states found themselves trapped in a ”gun-slave-gun cycle.” While some states acquired slaves in order to get more guns, other states sold slaves to get guns in order to protect themselves.

Inikori (1977) quantified the trade in firearms in some parts of West Africa and argued that there is a strong relationship between guns and the acquisition of slaves. Similarly, R. A. Kea and Richards point to the large volume of firearms imported into West Africa in the eighteenth century and the impact of these guns on interstate warfare, economic life, relations between Africans and Europeans, and the political organization of states along the Gold and Slave Coasts. Dahomey is often cited as a classic example of a militaristic state that expanded through the gun-slave-gun cycle. Dahomey maintained a slave-trade economy through a royal monopoly, exchanging slaves for guns. However, Werner Peukert (1978) points out, the bulk of the recent evidence seems to imply that there is nothing to suggest that Dahomey was completely subject to the influence of the Atlantic slave trade.

A number of scholars, including Paul Lovejoy, maintain that the export slave trade also indirectly increased the incidence of wars by exacerbating socioeconomic and political tensions within and between African states. Similarly, Inikori forcefully argues that ”the export slave trade helped to create values, political and social structures, economic interests, social tensions, and intra-group or inter-territorial misunderstandings . . . which encouraged warfare” (1982, p. 20).

|

The Alantic slave trade ARRIVALS IN AMERICA, 1451-1700 Destination |

Imports |

|

Europe |

50,000 |

|

Atlantic Islands |

25,000 |

|

Sao Tome |

100,000 |

|

Spanish America |

367,500 |

|

Brazil |

610,000 |

|

English Colonies |

263,700 |

|

French Colonies |

155,800 |

|

Dutch Colonies |

20,000 |

THE DEMOGRAPHIC IMPACT

Scholars have long debated the question of how many people were sent from Africa to the New World. Philip D. Curtin’s pioneering work, The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census (1969), estimates that the number of slaves sent to the Americas and other parts of the Atlantic basin from 1451 to 1870 was 9,566,100. Although his figures challenged old estimates, which ranged from 15 million to 50 million, Curtin nonetheless concluded that the impact on the continent was profound.

The debate over Curtin’s figures has divided scholars into different camps: those who accept Curtin’s estimates; those who essentially accept his conclusions, but argue that the estimates should be revised within a roughly 20 percent margin; and those who consider the estimates far too low to be meaningful. Paul E. Lovejoy (1982; 1983) and J. D. Fage (1978) are examples of scholars who have slightly modified Curtin’s figures, but not his conclusions. Inikori, by contrast, believes that Curtin’s estimate should be higher by about 40 percent. He argues (1982) that Curtin seriously underestimates the mortality rates of slaves between the time of their capture and their arrival in the New World; according to Inikori, at least 50 percent of slaves died before reaching the Americas.

There are also controversies about the demographic effects of slavery on African societies. Basil Davidson (The African Trade, 1961) and John Thornton (1977) argue that the demographic impact of the Atlantic slave trade on Africa was minimal. Thornton asserts that the population of the slave-exporting Sonyo province of the Kongo kingdom did not decrease. Similarly, J. C. Miller (1982) concludes that depopulation in Angola was less a consequence of trade than of periodic droughts, famines, and epidemics—natural disasters that caused population movements, which in turn fed the slave trade and replenished the populations of slave-providing regions.

On the other side of the debate, scholars like Fage, Rodney, Lovejoy, Inikori, Reynolds (1985), and Manning (1981; 1988) are convinced that the demographic impact was profound. In A History of Africa (1978), Fage argues that substantial numbers of lives were lost in Africa as a result of the violent means used to secure slaves, and that as a result West Africa experienced an overall decline in population. Manning’s simulation model (a statistical device used to measure demographic change under conditions of enslavement, slave trade, and slave exports) provides data that contradicts the findings of Thornton and Miller. For Western Africa, Manning’s analysis shows that population growth declined in response to the slave trade, particularly between 1730 and 1850. This trend was accompanied by a change in the sex ratio, in which the number of men fell to under 90 for every 100 women. Manning’s model suggests a cumulative decline of the West African population in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The region’s population in the early eighteenth century is estimated at twenty-two to twenty-five million with a growth rate of 0.3 percent throughout the era of the slave trade.

THE SOCIAL IMPACT

Patrick Manning (1981) shows that the ratio of males to females in the export trade affected marriage and birth rates in Africa. In support of this view, John Thornton (1983) points out that, among other things, imbalanced sex ratios altered the institution of marriage. While polygyny was already present in Africa at the time the trade began, the general surplus of women, he asserts, tended to encourage it and allowed it to become much more widespread. Claire Robertson and M. Klein, Inikori, and Lovejoy indicate that the ratio of women to men was generally 1:2. Be that as it may, gender imbalance had serious implications for population growth in many African states.

CONCLUSION

The Atlantic Slave Trade, the largest intercontinental migration in history, had serious implications for Africa as well as for those areas that received enslaved Africans. For one thing, it led to the emergence of African diaspo-ric communities in the ”New World.” For another, it created serious economic, political, and social problems in Africa. The loss of about 10 million African people severely hindered African development. The influx of firearms and the predatory activities of militaristic states and bands of individuals affected political development in many parts of the continent. The emergence of new lines of political allegiance and new political and economic elites altered centuries-old social formations. Finally, the gender imbalance that resulted from the slave trade affected African population growth. That the able-bodied segment of the population was the most desirable for slavers only worsened the demographic impact of the slave trade on Africa.

|

The Alantic slave trade |

|

|

ARRIVALS IN AMERICA, 1701-1800 |

|

|

Destination |

Imports |

|

Spanish America |

515,700 |

|

Brazil |

1,498,000 |

|

British Colonies |

1,256,600 |

|

French Colonies |

1,431,200 |

|

Dutch Colonies |

397,600 |

|

British North America/USA |

547,500 |

![tmp23E-19_thumb[1] tmp23E-19_thumb[1]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_LenCZlyza20/TSR7CETJbNI/AAAAAAAAJ_0/V-aLfMHKxh8/tmp23E19_thumb1_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)