When the Jesus movement moved from Palestine to the Greco-Roman world Africa became one of the major centers of Christianity, before the Islamic incursion in the seventh century, which disrupted the growth of African Christianity.

EARLY CONTACT WITH AFRICA

When the Portuguese first made contact with Africa in the fifteenth century, they were in search of four things. Number one, they were in search of a sea route to the spice trade in the Far East because Muslims controlled the land route through the Levant and the breadbasket in the Maghrib. Second, the Portuguese wanted to participate in the lucrative Trans-Saharan gold trade. Third, they initiated the “Reconquista” project to recover Iberian lands from the Muslims. Finally, they sought to reconnect with the mythical Christian empire of Prester John for the conversion of the heathens. The Portuguese monarch secured papal bulls, granting him powers to appoint clerical orders in the shoe-string empire discovered between 1460 and1520, stretching from Cape Blanco to Java. But Portugal was a small country and lacked the manpower to control and evangelize large territories. They occupied the islands and coastal regions of Africa, and traded from their feitoras (trading posts). Cape Verde Islands became the center of missionary enterprise and a refueling depot. Iberian Catholicism was a religion of ceremonies and outward show, formal adherence supplanted strong spiritual commitment. Court alliances used religion as an instrument of diplomatic and commercial relationship.

A missionary impact that insisted upon the transplantation of European models remained fleeting, superficial, and ill-conceived. Evangelization succeeded among the mestizo, mixed-race, children of the traders. Incursions into the kingdoms of Benin and Warri (part of present-day Nigeria) soon failed as the Portuguese found pepper from India more profitable to trade in. The only enduring presence of Christianity was in the Kongo-Soyo kingdoms (in present-day Angola), lasting until the eighteenth century.

In this region, some of the indigenous population was ordained to the priesthood, especially the children of Portuguese traders and some of the servants of white priests; however, the force of the ministry weakened with the changing pattern of trade, internal politics, and the disbanding of the Jesuits. A charismatic indigenous response to Iberian Christianity was manifested in the popularity of Vita Kimpa, a girl who claimed possession by St. Anthony and was martyred. Celebrated cases such as the conversion of the Monomotapa, the chief of Mashonaland in present-day Zimbabwe, were soon overshadowed by the counter-insurgence of the votaries of the traditional cults.

Iberian presence on the East African coast was dogged with competition from Indians and Arabs. The thirteen ethnic groups of Madagascar warred relentlessly against the Portuguese, while the Arabs of Oman recaptured the northern sector. Finally, other European countries challenged Portugal for a share of the lucrative trade that had turned primarily into slave trading. Memories of Iberian missionary exploits of yesteryear are broken statues and a syncretistic religion, Nana Antoni, in Cape Coast.

MISSIONARIES IN THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES

In the eighteenth century, twenty-one forts dotted the coast of West Africa because of intense rivalry; some had chaplains, many did not. These were poorly paid with shoddy trade goods. The Dutch and Danish experiments that employed indigenous chaplains (Quaque, Amo, Protten, Capitein) equally failed. The gospel bearers enslaved prospective converts. In the next century, abolitionism and evangelical revival catalyzed the revamping of old missionary structures and the rise of a new volun-tarist movement. Spiritual awakenings emphasized the Bible, the event of the cross, conversion experience, and a proactive expression of faith. Evangelicals mobilized philanthropists, churches, and politicians against the slave trade, to be replaced by treaties with the chiefs, legitimate trade, a new administrative structure, and Christianity as a civilizing agent.

Various groups of black people campaigned for abolition: in America, liberated slaves became concerned about the welfare of the race and drew up plans for equipping the young with education and skills for survival; Africans living abroad, like Ottabah Cuguano and Olaudah Equiano, wrote vividly about their experiences; and entrepreneurs like Paul Cuffee (1759-1817), a black ship owner and businessperson, created a commercial enterprise between Africa, Britain, and America.

Motives for abolition varied: religion, politics, commerce, rational humanism, and local needs each played a role. In England, the Committee of the Black Poor complained about the increasing social and financial problems caused by the number of poor liberated slaves. In America, those who fought on behalf of the British forces in the American Revolution (1775-1781) were relocated in Nova Scotia. They complained about their excruciating conditions. They had absorbed the liberal constitutional ideals of individual enterprise, personal responsibility, equality before the law, and freedom to practice one’s religion as the Republicans against whom they had fought. In the West Indies, “Maroons” had successfully rebelled against their slave owners and established communities of free people.

In 1787 the British government founded Sierra Leone as a haven for liberated slaves, but the colony nearly foundered because of inhospitable climate, poor soil, and attacks from local chiefs. In 1792, the Nova Scotians were dispatched to Sierra Leone, followed by the Maroons in 1800. They arrived with their own Baptist and Methodist spiritualities before any British missionary society was founded, and with a clear vision to build a new society under the mandate of the gospel that avoided the indigenous chiefs, who had been compromised through the slave trade. They set the cultural tone of industry and caused a mass evangelization of thousands of freed slaves in Sierra Leone between 1807 and 1864.

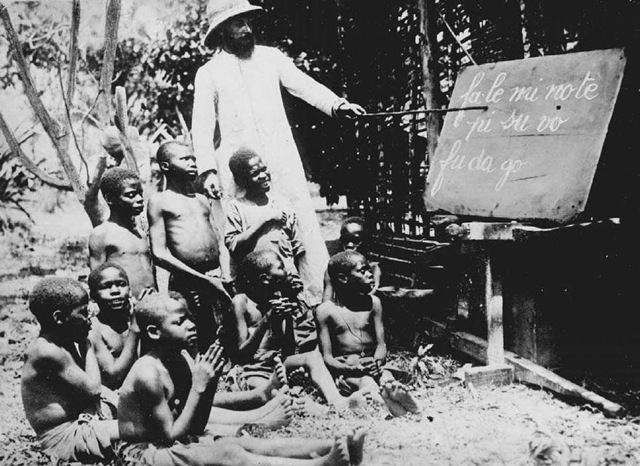

Reading Lesson in the Congo. A class of boys learns to read the local language in 1930 at the Jesuit school of Kwango in the Belgian Congo.

These freed slaves became agents of missionary enterprise throughout the west coast, serving variously as educators, interpreters, counselors to indigenous communities, negotiators with the colonial agents, preachers, traders, and leaders of public opinion in many West African communities. Others served in the Niger Mission. Samuel Adjai Crowther, made a bishop in 1864, signified their achievement. Furthermore, the American Colonization Society recruited enough African Americans to found Liberia in 1822, and from this period until the 1920s African Americans were a significant factor in the missionary enterprise to Africa.

African Christianity exploded because of an increase in the number of missionary bodies, men and women voluntarily sustained by all classes of society in various countries. The appeal of the gospel increased with education, translation of the scriptures into indigenous languages, and charitable institutions such as medical care and artisan workshops. These forces domesticated the message and equally changed the character of Christian presence.

As America warmed to foreign missions in the 1850s, it brought enormous energy, optimism and vigor, and human resources. The reasons included availability of technological power, civil and religious liberty at home, and other racial theories such as chosenness, covenant, burden, responsibility, civilization, manifest destiny— ideas that linked missions to the imperial ideology. The Roman Catholics revamped their organization and fund-raising strategies for missions in such a way that the rivalry with Protestants influenced the pace and direction of the spread of the gospel.

However, these changes coincided with new geopolitical factors: competing forms of European nationalism had changed the character of the contact with Africa from informal commercial relations into formal colonial hegemony. The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 partitioned Africa and insisted on formal occupation. It introduced a new spirit that overawed indigenous institutions and sought to transplant European institutions and cultures. Collusion with the civilization project diminished the spiritual vigor of the missionary presence and turned it into cultural and power encounters. This explains the predominant strategy of the missionary movements in southern Africa of forming enclaves and tight control of ministry that spurned the cultural genius of the people. The Catholic missionary presence in the Congo colluded with the brutality of King Leopold until an international outcry in 1908 forced him to sell the colony to Belgium. The abusive Portuguese presence in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, and Cape Verde Islands would later provoke an anti-clerical and Marxist response after the forced decolonization.

Indeed, the dominant aspect of the story became forms of African Christian initiatives, hidden scripts, and resistance to the system of control. First, malaria-bearing mosquitoes killed many white missionaries, compelling the recruitment of West Indian blacks for missions. Second, as missionaries sowed the seed of the gospel, Africans appropriated and read the translated scriptures from an indigenous, charismatic worldview. Native agency became the instrument of growth, giving voice to the indigenous feeling against Western cultural iconoclasm and the control of decision making in the colonial churches. Using the promise in Psalm 68:31 that Ethiopia shall raise its hands to God, Ethiopianism became a movement of cultural and religious protest. It preached emancipation and the hope that Africans would bear the burden of evangelization and build an autonomous church devoid of denominations and free of European control.

REVIVAL IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

In the twentieth century, a network of educated Africans was woven across West Africa to evangelize and incultu-rate an African Christianity. Typical of their ideology was Ethiopia Unbound by the Gold Coast lawyer Casely Hayford and The Return of the Exiles by Wilmot Blyden of Liberia. David Vincent rejected his English name, reclaimed the Yoruba name Mojola Agbebi, wore only African clothes, and left the white religious establishment by founding the Native Baptist Church without foreign aid. Products of missionary enclaves in Southern and Central Africa did the same; some were attracted to the black ideology and charismatic spirituality of the American African Methodist Episcopal Church. Racial tension thickened as World War I (1914-1918) approached. Both World War I and World War II (1939-1945) intensified African confidence, quest for education, and charismatic responses to the gospel. Four types of spiritual movements were prominent in the postwar eras, with Pentecostalism gaining prominence in the mid- to late twentieth century.

Christianity Adapted to the Local Culture. Often a diviner from the traditional religion appropriated some aspects of Christian symbols and the Christian message to create a new synthesis that was able to respond to the needs of the community. In seventeenth-century Kongo, Kimpa Vita started as an nganga, traditional diviner, a member of the Marinda secret cult, to claim possession by a Christian patron saint, St. Anthony. People perceived her as an ngunza or Christian prophetess; but the authorities executed her as a witch. Nxele and Ntsikana achieved an identical status among the Xhosa in the nineteenth century in spite of their differences. Nxele preached about one God for the whites and another for the blacks, and explained the massive European migration into the southern hemisphere as a punishment for killing their God’s son, a potential danger for the Xhosa. He turned his half-digested Christianity into a resistant religion. Ntsikana advised his people to ignore Nxele’s militant notions but apply the gospel to cure the moral challenges in the primal religion, and build an organized, united community so as to preserve the race in the face of the incursions of land-grabbing Europeans. Religious revivalism contested the political threat by the religion of invading white immigrants.

Prophet-Driven Christianity. A prophet emerged from the ranks of the Christian tradition emphasizing the ethical and pneumatic components of the canon to intensify the evangelization of the community or contiguous communities. Sometimes, the tendency was to pose like an Old Testament prophet sporting a luxurious beard, staff, flowing gown, and the cross. Some would-be prophets inculturated aspects of traditional religious symbols or ingredients of the culture, and supplanted the indigenous worldview with the Christian. The examples include Wade Harris, whose ministry started in 1910; Garrick Braide, who operated between 1914 and 1918; Joseph Babalola, who left his job as a driver in 1928 in West Africa; and Simon Kimbangu, whose ministry lasted through one year, 1921, in the Congo. Each was arrested by the colonial government and jailed: Harris remained under house arrest until death; Braide died in prison in 1918; Kimbangu’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and exile at the intervention of two Baptist missionaries. He died at Elizabethville in 1951. Babalola was released through the plea of some Welsh Apostolic agents.

The Indigenous Church. A wave of African indigenous churches arose all over Africa at different times before World War I and especially during the influenza epidemic of 1918. Dubbed as Aladura in West Africa, Zionists in Southern Africa, and Abaroho in Eastern Africa, some caused revivals, others did not; but they tended to emerge from mainline churches by recovering the pneumatic resources of the translated Bible. They deployed traditional Christian religious symbols. Soon differences appeared based on the dosage of traditional religion in the mix: the nativistic forms were neopagan; the vitalistic used occult in the quest for power; the revivalists clothed primal religion in Christian garb; the messianic leader presumed to be one or the other of the Trinity. Sunday and Sabbath worshippers emerged among them. Scholars note their creativity and enduring contributions to African Christianity. They served as political safe havens for the brutalized Africans.

Charismatic Movements. Sometimes charismatic movements arose within churches challenging doctrine, polity, liturgy, and ethics, and those churches seeking to enlarge the role of the Holy Spirit within their faith and practices. Hostile church leaders often excluded the attackers who wanted to form new churches or ministries, while charismatic movements remained within the churches. Some were short-lived revival movements; others became permanent. Examples include the Ibibio Revival that occurred within the Qua Iboe Church in eastern Nigeria in 1927; the Kaimosi revival that occurred within the Friends Africa Mission/Quakers in western Kenya in 1927; the Balokole revival that swept through the Anglican church in eastern Africa from 1930; and the Ngouedi revival that occurred among the Swedish Orebro Mission in 1947 and resulted in the Evangelical Church of Congo (EEC).

The Pentecostal Movement. Excluded members of charismatic movements birthed contemporary Pentecostalism in Africa. The young people, nicknamed as aliki in Malawi, began to conduct large revival meetings in the 1960s but especially from the 1970s in many African countries. They traveled from one place to another, denouncing with fire and brimstone sermons the sinful-ness and evils of everyday urban life. The phenomenon became even more pronounced in the 1980s. They challenged the predominance of either voodoo or Islam or Roman Catholicism. Later, the movements in various countries linked through the activities of the students’ organization, FOCUS (Fellowship of Christian University Students), and the migrations of students within the foreign-language educational programs.

Most revivals occurred during the period between 1914 and 1950 when missionary control reigned supreme, colonial power and white settlers colluded, and labor problems and racial exploitation predominated. Charismatic religiosity provided a survival technique for Africans in the midst of the disquiet of those years and stamped African Christianity with an identity that contested missionary control and its monopoly of Christian expression.

CHANGES IN THE MID- TO LATE TWENTIETH CENTURY

In the same period of the early to mid-twentieth century, many religious forms flourished. The mainline denominations engaged in strong institutional development with schools, hospitals, and other charitable institutions; evangelized the hinterland areas; essayed to domesticate Christian values by confronting traditional cultures; and, in the Kikuyu case, triggered a rebellion that had enormous consequences. Education enabled many people to access newspapers and magazines and remain connected with Asia and Europe. A number of cultic and esoteric religious organizations advertised their wares in magazines and newspapers. It became the pastime of the literate few to scour newspapers and magazines for advertisements and mail orders for amulets, charms, rings, and other cultic paraphernalia from Asia to ensure success in examinations, gain promotion, and ensure security in the competitive and enlarged horizon of urbanity. Freemason and Rosicrucian lodges dotted the urban capitals of various countries.

Islam expanded more in the wake of improved transportation and commercial opportunities created by colonialism than many jihads would have accomplished. Since most of the African population still lived in the rural areas, traditional religion predominated many countries. Certain forces challenged missionary Christianity in Africa: the two world wars weakened missionary resources and encouraged black nationalism. The decolonization process that followed ineluctably produced new state ideologies that challenged the missionary heritage; religious nationalism compelled the mission churches to indigenize their structures and message. Missionary response to nationalism was informed by individual predilections, the negative racial image of Africans, and some liberal support. Regional variations abound as those in the settler communities responded with fright and the bulwark of apartheid laws.

The wind of change exposed the weak roots of the missionary infrastructure: few indigenous clergy, a dependency ideology, undeveloped theology, poor infrastructure, and above all little confidence in indigenous leaders. From the 1950s, some hurried to train indigenous priests and to ally with nationalists, because the educated elites were products of various missions and their control of power could aid their denominations in the virulent rivalry for territory. This strategy entangled Christianity in the politics of independence.

Matters went awry when the elites grabbed the politics of modernization, mobilized the states into dictatorial one-party structures, castigated missionaries for under-developing Africa, promoted neo-Marxist rejection of the dependency syndrome, and seized the instruments of missionary propaganda such as schools, hospitals, and social welfare agencies. The implosion of the state challenged the churches, but the failure of the states produced a rash of military coups and regimes, abuse of human rights, and economic collapse. Poverty ravaged many African countries. The militarization of societies intensified interethnic conflicts and civil wars. Refugee camps filled to the brim. Natural disasters such as drought in the Horn of Africa worsened matters. Part of the problem could be traced to weak leadership, and part to external forces that used the continent as fodder in the cold war, patronized dictators, exploited the mineral resources, and manipulated huge debts that have burdened and crippled many nations permanently.

African Christianity grew rapidly against the backdrop of poverty and the legitimacy crisis. As civil society was decimated, Christianity remained the survivor. Christian leaders were chosen in one country after another to serve as the presidents of consultative assemblies that sought to renew hope and banish the pessimism that imaged African problems as incurable. Other developments include: (1) African Christian theologies from the mid-1970s enabled a critique of inherited theologies; this sustained a black revolution against apartheid in South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe; and (2) the charismatic movements that exploded in the 1970s, and have continued to change shape in every decade, absorbing American prosperity preaching in the 1980s, and reverting to traditions of holiness and intercessory prayer in the 1990s. This form has a “fit” that answers to questions raised within the primal worldviews; it provides mechanisms for coping with economic collapse; it revitalizes and sets missionary message to work with inexplicable power of the Holy Spirit.

The missionary movement has charismatized the mainline churches, flowed from urban centers into rural Africa, engaged the public space, and experimented with new forms of ministerial formation. A third development is the rise of Christian feminist theology, challenging the churches to become less patriarchal. Through many publications and programs, churches are being compelled to ordain women and increase their participation in decision-making processes. Contemporary Africa resembles the early Christianity in the Maghrib.