1893-1976

Mao Zedong was born on December 26, 1893, in Shaoshan, Hunan Province, China, and died on September 9, 1976. Mao was the most influential leader and theorist of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

In the aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution, Mao, while staying in Beijing, started to study Russian Bolshevik theories and methods in a search for better ways to save a weak and divided China. The unsatisfactory settlement after World War I in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles concerning the transfer of German possessions in China to Japan triggered the anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement in China. This movement brought Mao closer to Marxism and Leninism.

Mao was one of the founders of the CCP, formed in July 1921. From 1924 to 1927, under the auspices of the United Front of the CCP and the Nationalist Party (Guomindang, GMD), Mao organized labor unions and peasant associations and participated in the Nationalist Revolution against warlords and foreign imperialists. Mao stressed the central role of peasants in rural class struggles. It remained the core of his belief that the semicolonial status of China—foreign meddling and mauling inside China, the resulting lack of industrial development and a strong urban proletariat class, the warlord government—meant that the Chinese revolution would have to take the form of poor peasants versus rich landlords in rural areas.

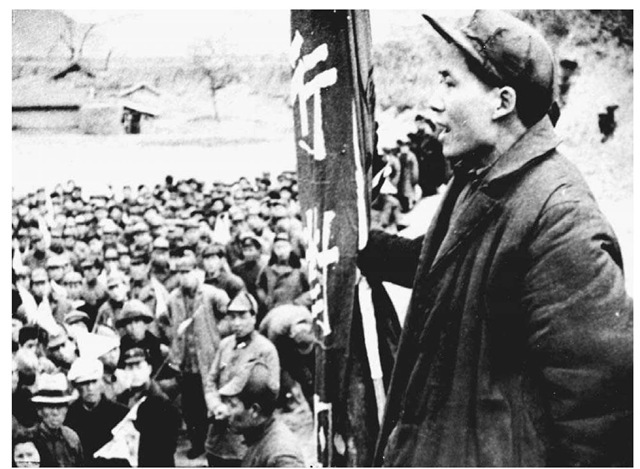

Mao Zedong, November 12, 1944. Mao Zedong (1893—1976), the future leader of Communist China, rallies a group of Chinese people to the Communist cause.

From 1927, when a breach between the CCP and GMD occurred, to 1934, Mao established rural bases in Jiangxi and Fujian provinces in southeast China, and engaged in guerrilla warfare to resist the superior GMD forces. From 1934 to 1935, the CCP Red Army was driven out of its rural soviets (CCP’s armed territories/ authorities in adoption of the name of the Soviet government) and forced to relocate to Yan’an, Shaanxi Province, in northwest China. The nearly 9,700-kilometer (6,000-mile) move became known as the ”Long March.”

In Yan’an, Mao consolidated his power and developed political, social, and economic models for the future China. After the eight-year war against Japan ended in 1945, civil war broke out between the CCP and the GMD, despite American attempts at mediation. The defeated GMD retreated to Taiwan, and the CCP’s victory in the civil war led to the founding of the PRC in 1949, with Mao as its chairman.

In spite of constant friction in its relationship with the Soviet Union (USSR), which eventually resulted in an open split in the early 1960s, Mao chose to follow Russia’s Stalinist system to implement socialism in the PRC—party supremacy in the government and the army, a state-planned economy with an emphasis on heavy industry, and agricultural collectivism. To achieve his goals, Mao initiated mass campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward (1958-1960, a disastrous social and economic movement that was intended to increase agricultural and industrial production through eradication of private land ownership, moral incentives, and mass labor) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976, a violent mass movement against the establishment, which brought about turmoil and enormous suffering to Chinese people).

Against the backdrop of the Cold War rivalry between the USSR and the United States, Mao’s China, sympathetic to North Korea’s pro-Moscow Pyongyang regime, went into the Korean War (1950-1953) in direct confrontation with the United States. In support of the GMD in Taiwan, the United States had adopted a non-recognition policy toward the PRC until the visit of American president Richard Nixon (1913-1994) to China in 1972 and the final normalization of Sino-American diplomatic relations in 1979.

From the early 1940s on, Mao’s revolutionary ideology and methodology were labeled ”Mao Zedong Thought.” Central to Mao Zedong Thought is his application of Marxist and Leninist theories of world proletarian revolutions to the actual conditions of China. Mao’s ”Three Worlds” idea (1974) played an important role in forming alliances in world affairs among the third world countries of Africa, most of Asia, and Latin America.

As for Mao’s legacy, some view him as an evil Chinese ”Lord of Misrule,” who was responsible for initiating tumultuous political, social, and economic changes that caused widespread suffering among millions of people. Some argue that Mao’s contributions to the Chinese nation—the restoration of China’s independence and sovereignty, the unification of China, and the construction of socialism—far exceed his errors. For ordinary Chinese, Mao remains an iconic figure, which attests that the Chinese have their own memories of their own past and their own leaders.