The London Missionary Society (LMS), established in 1795, was one of a number of voluntary foreign missionary societies formed throughout Western Europe at the end of the eighteenth century. The evangelical revivals that inspired lay humanitarian activity at home, coupled with an increased sense of Britain’s moral responsibilities to populations in its growing empire, led to the wave of foreign missions that crested across the nineteenth century. The founders of the LMS had been preceded by the founders of the Baptist Missionary Society (1792), and were followed by evangelical colleagues who established organizations in Scotland and England—in Scotland, the Edinburgh and Glasgow Missionary Societies (both 1796), and in England, the Society for Missions to Africa and the East (1799), which from 1812 was known as the Church Missionary Society. The LMS joined with the Commonwealth Missionary Society to become the Congregational Council for World Mission in 1966, and that organization evolved into the Council for World Mission in 1977.

The nondenominational founding principles of the Missionary Society, as the LMS was known until it was renamed in 1818, were preserved throughout its institutional history despite the fact that the organization quite quickly became almost exclusively associated with the Congregational Churches in Britain. Membership of the society was based on annual subscription. Members met annually in May to deliberate, to vote on administrative decisions, to be introduced to and send off new missionaries and those on furlough, and to celebrate the life and work of the institution. The formal administrative work of the LMS was undertaken by a voluntary Board of Directors, administration was managed by a Home Secretary, and a Foreign Secretary exchanged personal and business correspondence with the missionaries employed by the society all over the world. In 1810 this core organizational structure was expanded to include a growing number of committees, some region-specific, which oversaw the increasingly complex work. These included an Examinations committee—the work of which was to screen and train mission candidates. In 1875 this group was joined by a Ladies’ board, which functioned until 1891, when it was replaced by a ladies’ examination committee after women were allowed to join the Board of Directors. These central committees were also supported by a network of voluntary local auxiliary groups, organized and supported mostly by women, that disseminated information about missions and raised the funds—in small increments—needed to support administrative and mission work. What seems clear is that women’s decision-making power, both in Britain and in foreign work, lay in their ability to exercise skill in working within what was a male-dominated institutional organization. As such, women operated through familial and social networks, and when attempting to influence decision making were bound by the necessity of avoiding the sort of direct confrontations they were certain to lose.

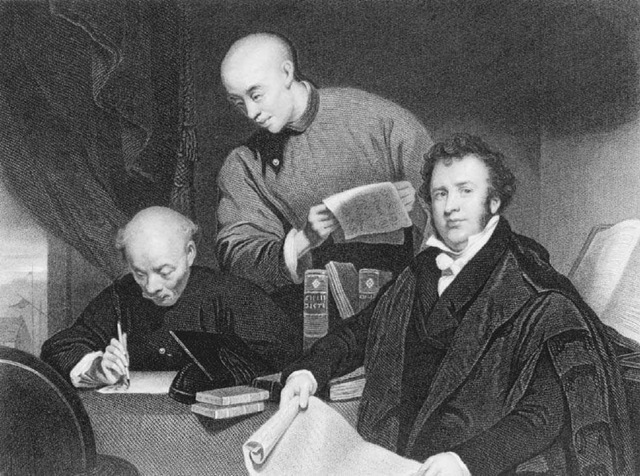

Robert Morrison (1782-1834). The Scottish missionary Robert Morrison (right), the first Protestant missionary in China, is shown in the early 1800s with Chinese assistants as they prepare Morrison’s translation of the Bible.

The LMS sent its first missionaries abroad in 1796, to Tahiti, and by 1945 it had sent 1,800 men and women to engage in foreign mission work. LMS missions to the South Seas were marked by the establishment of small but vibrant Christian communities, like those that resulted in the self-governing church in Papua. They were also marked by dramatic events, such as the fate that befell John Williams, who joined the mission in 1817 and became one of the LMS’s most famous martyrs. Williams’s criticism of existing LMS practices, his broad travel and dynamic evangelism, and his violent death in Erromanga in 1839 made him an inspiration to future mission workers; the society subsequently named a series of seven missionary boats after him, and wooden ship-shaped boxes labeled ”the John Williams” were used by mission workers collecting the change that supported mission work. A mission venture was established in eastern Siberia in 1818 when two missionaries and their wives traveled to Irkutsk to evangelize the Buryat before moving on to work with Mongols in China. Other missions were established in Greece and Malta, in North America, and to the Jews in London during this era.

The main fields of LMS activity across the nineteenth century were India, China, Southeast Asia, the Pacific, Madagascar, Central and Southern Africa, Australia, and the Caribbean. The LMS hired a significant number of Scottish missionaries throughout its history. Because Scots tended to be better educated than their English colleagues, they made up the majority of the Society’s medical missionaries and provided the hearts and hands for work in the east, where better-trained candidates were deemed necessary to counter the arguments of Hinduism and Islam. LMS work in India was first begun in 1798 outside of Calcutta; work was initiated after that in western India, and then in southern India, in 1805. LMS work in China was begun by Robert Morrison, who arrived in Canton (Guangzhou), the only port open to foreigners, in 1807; he and the colleagues who followed him focused on translation and publishing. However, the Qing Imperial government was successful in refusing Westerners entry to the rest of China until the mid-nineteenth century, and it was not until after 1843 that LMS workers began to slowly work their way into mainland China. LMS missionaries were present in the early days of the Sierra Leone settlement, but sustained LMS activity in Africa began in 1799 in Southern Africa, and spread north. A series of LMS missionaries in Southern Africa offered an important and sustained critique of settler actions, colonial activity, and imperial policy; David Livingstone, the society’s most famous popular missionary, traveled north from there in his famous journeys as missionary and explorer. In each of the territories the LMS operated in, a combination of preaching, institution-building, and social outreach work was met by a variety of responses ranging from acceptance to adaptation, to outright rejection.

Both because of and in spite of the efforts of mission societies like the LMS, Christian churches were established throughout the world that exhibited beliefs and practices quite distinct from anything found in the West. Since their establishment, many of these churches have developed to a size and with a dynamism that has outstripped the Western church.