Cotton, a plant of the mallow family, produces fibers that can be woven into cloth. It has been valued since antiquity and its cultivation was an important factor stimulating European colonialism in regions of Asia, Africa, and the Americas; it is still a major trade commodity. Numerous species of cotton exist, but four are of commercial importance: Gossypium arboreum (native to Asia), G. herbaceum (native to Africa), and G. hirsutum and G. barbadense (both native to the Americas). Cotton plants originated in tropical regions, but are now grown worldwide in a variety of climate zones where adequate heat and water are available. The cotton plant produces capsules, called bolls, in which seeds are surrounded by a fluffy fiber, or lint. Cotton producers generally divide cotton into two types: short-staple cotton, which has shorter fibers about one inch long, and long-staple cotton, which has fibers reaching two inches in length. Long-staple cotton is more valuable, as it produces a higher quality cloth. Most cotton grown today produces white or cream-colored fibers, but many other colors, including yellow and brown, also exist. Cotton cloth is comfortable in hot climates and is insect resistant, easily washable, lightweight, and easily dyed. Cotton seeds have a variety of industrial applications, including being used in the manufacture of oils, soaps, detergents, cosmetics, fertilizers, and animal foods.

Cotton was known and used in ancient Egypt, India, China, and the Americas. Europeans probably learned about the value of cotton garments as a result of British and French commercial activities in India in the seventeenth century. Cotton fibers brought back from India led to the establishment of a cotton textile industry in Britain, especially in the city of Manchester. Cotton textile producers originally faced restrictions placed on them by the government at the behest of wool growers, who realized that cotton cloth would compete with woolens. These restrictions were largely unsuccessful, however, as the public increasingly demanded cotton cloth. Cotton in seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century England was spun at home as a cottage industry, but with the Industrial Revolution production began to shift to large industrial mills. New spinning techniques and new mechanical looms stimulated the growth of the cotton textile industry by making cotton production easier and less expensive. The invention of the cotton gin by the American Eli Whitney in 1793 allowed cotton seeds to be easily removed mechanically, eliminating the slow and laborious process of removing the seeds by hand and lowering the cost of cotton production.

To sustain the increased levels of production made possible by industrialization, the British needed new sources of cotton. Both Egypt and the American South emerged as important centers of cotton cultivation supplying British textile mills. India was also a producer, though its cotton was generally considered to be of lower quality, and lack of adequate infrastructure in India made export difficult. The demand for cotton and the resultant need to secure cotton supplies prompted British imperial expansion, and made Egypt and the American colonies especially important. The same applied to the French, who established cotton plantations in their own colonies in the West Indies and in West Africa.

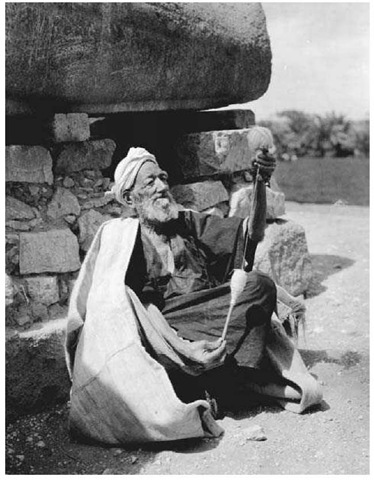

Spinning Cotton, 1920s. This elderly Egyptian man spins cotton by hand using a simple, centuries-old spinning technique.

COTTON AND THE RISE OF MODERN EGYPT

Cotton was essential in the rise of modern Egypt, which became a major cotton-producing region in the nineteenth century and continues to be a major producer today. The rise of Egypt’s cotton industry was largely due to Muhammad ‘Ali (there are various spellings of his name), ruler of Egypt from 1805 to 1848. Muhammad ‘Ali’s consolidation of Egyptian power and his early modernizing policies have earned him the name ”Father of Modern Egypt.”

Muhammad ‘Ali (ca. 1769-1849) was born in Albania. As a soldier in the Ottoman army, he rose through the ranks, eventually becoming governor of Egypt, which was then a part of the Ottoman Empire. An autocratic, ambitious, clever, and crafty person, he quickly became the ruler of a virtually independent Egypt, after eliminating the Mamluk rulers in 1811. Muhammad ‘Ali recognized that he could enhance Egypt’s independence by using profits generated by cotton exports to expand the military and develop infrastructure. He used cotton profits to finance military expeditions into Syria and other Ottoman territories and to establish industry in Egypt.

Muhammad ‘Ali encouraged European experts and technicians to settle in Egypt. Louis Alexis Jumel (17851823), a French textile engineer, came to Egypt in 1817 as the director of a spinning mill. A few years later Jumel discovered a cotton bush in a Cairo garden that was producing a superior kind of cotton, with a long staple and strong fiber. Jumel tried growing this cotton himself, and was successful in producing cotton of much greater quality than that previously grown in Egypt. Realizing that this new kind of cotton could revolutionize Egypt’s cotton industry and generate large profits for the Egyptian government, Muhammad ‘Ali financially supported Jumel’s cotton research.

The new Jumel cotton was much in demand in Europe. Under Muhammad ‘Ali’s orders, Egyptian peasants, called fellahin, began extensively planting Jumel cotton in the delta of the Nile River. The government monopolized the cotton industry, buying raw cotton directly from the growers and selling it directly to European traders. Muhammad ‘Ali also organized irrigation projects, provided credit and seed to the peasants, and brought in additional technicians from Europe. Cotton growing required a lot of labor (as did ginning), but under an authoritarian government the peasants had little choice but to accept the orders to grow cotton; the peasants, however, also realized that they too could profit from growing cotton. Muhammad ‘Ali tried importing American Sea Island cotton, which was considered the world’s best in quality, but this experiment was not successful, as the American plant did not grow well in Egypt (and actually caused an overall decline in cotton output as new fields were dedicated to it). Eventually, however, Sea Island cotton was successfully crossed with the Jumel variety.

By 1836 cotton accounted for 85 percent of Egypt’s revenue generated from agricultural commodities, and cotton industries employed about 4 percent of the population, or about two hundred thousand people, during the 1830s. Muhammad ‘Ali also constructed factories in Cairo to gin, spin, and weave cotton, bringing him into conflict with the British, who wanted Egypt to produce only raw cotton and feared that textile manufacture would compete with their own cotton mills. Muhammad ‘Ali attempted to impose an import substitution policy in Egypt, to protect Egyptian industries, to limit the importation of foreign textiles, and to achieve a favorable balance of trade, but after Egypt’s unsuccessful military ventures in Syria, he was forced to agree to the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1838, which abolished free trade and undermined Egyptian industry. Muhammad ‘Ali was successful in Syria until the Great Powers, especially Great Britain and France, decided he was becoming too powerful and set out to clip his wings by intervening militarily. Against the Ottomans he had done very well.

Egypt gradually became incorporated into the greater European economic system as a supplier of raw materials. The cotton boom of 1861 to 1866, during the American Civil War, raised prices and increased production. Cotton cultivation had four major effects on the Egyptian state. First, it changed the nature of agriculture, shifting the focus to export crops and especially cotton. Second, it changed Cairo’s relationship with the rest of the country, as the capital became an industrial center and purchaser of cotton, even as governmental decentralization gave the provinces greater political autonomy. Third, it integrated the Egyptian economy into the European one. Fourth, it increased state profits and allowed Egypt to engage in industrialization and modernization. Overall, cotton production helped Egypt assume a greater level of economic independence and control than was typical for colonized states, and helped bring about its current position as a leading Arab country.

COTTON IN THE AMERICAN SOUTH

The development of English cotton mills in the seventeenth century stimulated the demand for raw cotton, and Britain attempted to ensure supplies by encouraging plantations in British colonies. The American South was highly suitable for cotton growing. Up until the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, only the long-staple, or American Sea Island, cotton (G. barbadense) was profitable. This cotton could only be grown in the hot and humid coastal areas of the Carolinas and Georgia. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 allowed the short-staple cotton, G. hirsutum, to be easily deseeded and thus cheaply produced. This type of cotton grew well in interior regions of southeastern and western North America, and its increased production soon led to the confiscation of Native American lands and stimulated extensive settlement in such states as Alabama and Mississippi, which became centers of the cotton industry. Because cotton production required cheap labor, African slavery became the basis of the production system. The expansion of the cotton industry increased the demand for slaves.

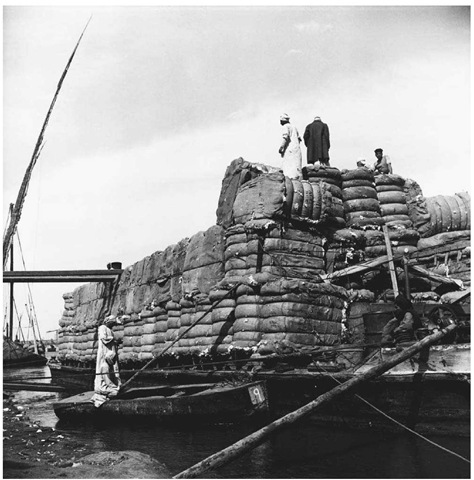

Egyptian Cotton Ready for Transport on the Nile River. Large bales of cotton are loaded on a barge at the banks of the Nile River in Egypt in the 1950s.

Cotton was important in the development of the United States as an industrial power. In New England states such as New Hampshire and Massachusetts, entrepreneurs established their own cotton mills, producing textiles that competed with those of Britain. New England competed with Britain both for the supply of raw cotton and for markets for cotton textiles. New England cotton mills provided employment and, as output increased, European immigration was encouraged to meet the demand for new mill workers. Cotton profits were also used to stimulate other industries, helping the United States to become an industrial country not long after its independence.

Though cotton had an important role in the formation of American industries, it was also a source of conflict. Mills were located in northern states; production in the South was dependent on slave labor. The conflict over slavery in the United States was largely stimulated by cotton and was a major cause of the Civil War (1861— 1865), although much cotton was also produced by those not owning slaves. The expansion of cotton production in states of the lower Mississippi Valley also stimulated conflict over the question of whether or not these new states should allow slavery, as did Northern protective tariffs on these states’ textile products. During the Civil War the North blockaded Southern ports, so that cotton could not be exported to Britain. This action drove up the worldwide price of cotton, and Egypt was one of the main beneficiaries of an increased price.

After the Civil War, the cotton industry was in a difficult position, as crops had been destroyed by war, the plantation system had broken down, and slavery was abolished. In the 1880s industrial cotton mills began to relocate from New England to Southern states, taking advantage of lower wages. By 1929 over half of the country’s cotton mills were in the South. In 1894 the boll weevil, a small insect that attacked cotton plants, devastated much of the Southern cotton industry, contributing to the region’s increasing poverty. Cotton production began shifting to Texas and California, which today are the two leading producing states, by 1930, and was dominated increasingly by large agribusinesses, rather than family farms. Cotton’s difficulties continued into the 1980s, with the development of new synthetic textiles and the relocation of many mills to Asia. Within the past few decades, however, cotton has experienced a resurgent demand: Prices have risen and production has increased as consumers return to natural fibers.

Cotton was an important crop during the colonial era and remains one today. It is used for such textiles as the denim used in jeans, important in American and global clothing fashions. It helped stimulate economic development in places such as Egypt, whereas in other areas, such as the American South, it retarded economic growth while allowing milling regions such as Britain and New England to prosper. Overall, cotton played a key role in stimulating Western imperial expansion and industrialization.