Since the beginning of the motion picture industry, Western colonialism has been one of the themes, and at times one of the popular themes, of European and American movies. Cinema continued the nineteenth-century western European and American trend of telling romantic, exotic, and patriotic stories of expansion, conquest, and—increasingly—mission, or bringing the benefits of “civilization” to the “inferior races.” Such stories had earlier been told in paintings, popular books, museums, illustrated journals, juvenile literature, and comics. Over the decades of the twentieth century, films with “imperial” and “colonial” themes celebrated and glorified imperial adventures and colonial triumphs and crises. Popular movies projected more myth than reality regarding the nature of colonialism, particularly as experienced from the indigenous African and Asian perspectives.

After World War II (1939-1945), and particularly by the 1970s and 1980s, Western filmmakers began to portray colonial encounters in more complex and nuanced ways. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, cinema around the world, from the perspective of both filmmakers and audiences, remained drawn to the themes of Western colonialism and, particularly, the difficult issues and problems created by the colonial encounters between Europeans and non-Europeans.

Colonialism at the movies began at the dawn of the motion picture industry in the late 1900s. A fifty-second reel about the French colony of Annam (central Vietnam) in Indochina was made by Gabriel Veyre (1871-1936), a collaborator of the Lumiere Brothers (Auguste [1862-1954] and Louis Jean [1864-1948] Lumieere, the inventors of cinema in Europe) in 1897. This short, entitled Enfants annamites ramassant des sape-ques devant la pagode des dames, shows two French women giving money to a group of Vietnamese children who scramble and fight for every coin.

Only a small fraction of French films made in the 1920s and 1930s were colonial in subject or made in exotic locations. The Franco-Moroccan films of the 1920s respected local Berber customs, and the best “colonial” French films of the era, Le Sang d’Allah (The Blood of Allah, dir. Luitz Morat, 1922), Itto (dir. Jean Benoit-Levy, 1934), and Pepe le Moko (dir. Julien Duvivier, 1937) provided realistic and ethnographically informed representations of North Africans. Pepe le Moko was popular in the United States. It was remade by Hollywood as Algiers (dir. John Cromwell, 1938). These films helped establish the exotic casbah in the imagination ofAmericans and contributed to the success of Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca (1942). The American cartoonist Chuck Jones (1912-2002), who joined Warner Brothers in 1938, apparently was inspired by Pepe le Moko when he created his character Pepe Le Pew, who was debonair in a skunklike way.

French film critics constantly praised French filmmakers for their attention to actualitees—not unlike nineteenth-century art critics who praised the North African paintings of French artist Eugeene Delacroix (1798-1863) for their authenticity and transparency. French film critics, of course, reacted against the American and British “French Foreign Legion” films of the era, such as The Sheik (dir. George Melford, 1921), Son of the Sheik (dir. George Fitzmaurice, 1926), The Spahi (1928), and Beau Geste (dir. Herbert Brenon, 1926; and William Wellman’s 1939 remake). French filmmakers, however, made their share of colonial adventure stories that shored up the idea of empire and idealized the Foreign Legion as the “thin white line” defending civilization from the Arabs. David Henry Slavin counts fifty such films set in North Africa in the 1920s and 1930s that “legitimated the racial privileges of European workers, diverted attention from their own exploitation, and disabled impulses to solidarity with women and colonial peoples” (2001, p. 3).

The British, with an empire upon which the sun never set, had uncounted colonial topics and stories that provided themes for popular feature films from before World War I (1914-1918) to the 1950s. The British and Colonial Kinematograph Company began the production of films in 1908 and produced a number of movies in colonial locales. The British Board of Film Censors, beginning in 1912, insured that “controversial” issues were avoided and only “wholesome imperial sentiments”—as the dominion premiers agreed in 1926— would be disseminated in the three thousand cinemas operating in Britain in the late 1920s (MacKenzie 1999, p. 226).

In the mid-1930s the Hungarian-born British producer Alexander Korda (1893-1956) produced his “Empire Trilogy,” three popular films directed by his brother Zoltan Korda (1895-1961) that glorified the British Empire: Sanders of the River (1935), The Drum (1938), and The Four Feathers (1939). Sanders of the River, about a British district commander allied with an African chief played by the American actor Paul Robeson, so offended Robeson’s sense of racial stereotyping that he attempted unsuccessfully to buy the rights to the film and all prints to prevent its distribution. The Drum, about a native Indian prince who gave assistance to a Scottish army regiment to overcome a rebel tyrant, triggered Hindu-Muslim riots in Bombay in 1938.

One of the favorite colonial stories, a 1902 novel by the British author A. E. W. Mason (1865-1948) about the courage of a former British soldier during the Sudan campaign of 1898, The Four Feathers was first made into a film during World War I and was remade by Zoltan Korda in 1939. The 1939 film presented the Sudanese enemy, the Arab dervishes, and the African ”Fuzzy Wuzzies” as mindless warriors in the service of a madman. These and other British films with colonial themes of the 1930s offered little justification for empire other than, writes Jeffrey Richards, ”the apparent moral superiority of the British, demonstrated by their adherence to the code of gentlemanly conduct and the maintenance of a disinterested system of law and justice” (quoted in Nowell-Smith 1996, p. 364). (Mason’s 1902 novel has appeared on film seven times, including a 2002 version by the Indian director Shekhar Kapur. Kapur’s film, unlike the previous ones, injected a dose of anti-imperialism in its double perspective of how British imperialism affected the subordinate native people and the British and native soldiers who enforce foreign rule.)

Italy’s film industry during the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) in the 1920s and 1930s was intended to create statist, nationalist, and imperialist propaganda, as Mussolini noted when he paraphrased Russian Communist leader V. I. Lenin (1870-1924): ”For us cinema is the strongest weapon” (quoted in Nowell-Smith 1996, p. 354). In fact, however, official, ”fascist” films constituted only a small percentage of Italian productions between 1930 and 1943. Fascist filmmakers, however, did produce movies about Italy’s ”African mission” with Squadrone bianco (White Squadron, dir. Augusto Genina, 1936) and Sentinelle di bronzo (Bronze Sentries, dir. Romolo Marcellini, 1937). The great costume drama and epic Scipione I’Africano (Scipio the African, dir. Carmine Gallone, 1937) reminded Italian audiences that Italian (Roman) soldiers had conquered Africa before and would do so again.

The Nazi state in Germany through the Ministry of Propaganda made many more films than the Italian fascist state, but there was little interest in overseas imperialism. Of the more than one thousand feature films produced in Germany between 1933 and 1945, few dealt with subjects other than Germany. La Habanera (dir. Douglas Sirk, 1937) and Germanin (dir. Max Kimmich, 1943), about Latin America and Africa respectively, focused on fever, sickness, and premature death.

The Soviet Union, officially anti-imperialist, made internationally recognized avant-garde films in the 1920s, but under Joseph Stalin (1879-1953) in the 1930s and 1940s production declined, as did quality. During World War II and the buildup to the war, Soviet cinema fell back on Russian imperial themes to promote nationalism and support for the state. Kutuzov (dir. Vladimir Petrov, 1944) presented Mikhail Kutuzov (1745-1813), the general who saved Russia from the Napoleonic invasion, as a loyal Russian and brilliant strategist. The great Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948) in Ivan grozny (Ivan the Terrible, part 1, 1945) depicted the sixteenth-century czar as a troubled character but great national hero. The film was begun on Stalin’s request, but the dictator viewed it as a critique as his own autocracy and banned it. During the Stalin years, the Soviet republics were permitted to make their own film epics about national heroes (Bogdan Khmelnitsky [dir. Igor Savchenko, 1941] in Ukraine, for example), but the Soviet censors made sure that these were heroes who had never fought against Russian oppressors.

By 1929 over 80 percent of the world’s feature films came from the United States, and most of those from Hollywood, California. The United States had long viewed itself as an anti-imperialist nation, despite its expansion across the transcontinental West, its seizure of Native American lands and Mexican provinces, and its late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century adventures in overseas acquisitions of Hawaii, Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and the Panama Canal Zone. American filmmakers, and apparently American audiences, were not interested in any American ”empire” other than the ”Wild West” and cowboys and Indians.

The western dominated American cinema from the silent period through the 1950s. Not unlike French and British colonial films, American westerns contrasted white civilization and Indian ”savagery,” as well as the conflicts within newly settled colonial societies. Many American western films, beginning with The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1913) directed by D. W. Griffith (1875-1948), present the advance of the frontier as a triumph of character and heroism. Not all westerns before the 1960s and 1970s, however, were vehicles for anti-Indian propaganda. Hundreds of early silent films were based on the popular Wild West shows of Buffalo Bill, Broncho Billy, Tom Mix, and others that had genuine Indian performers who provided the attraction of an exotic and cliched past. A number of feature films, from Griffith’s The Squaw’s Love (1911) to Howard Hawks’s Broken Arrow (1950) and John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), presented sympathetic portraits of Indian life and relations with whites, and complex observations on the nature of American racism. The famed ”Cavalry Trilogy” directed by John Ford (1895-1973)— Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950)—was scathing in its portrayal of U.S. Indian agents, cavalry officers, and other whites who took advantage of the Apaches or misunderstood them.

Americans were as interested in the adventure and romance of the British and French overseas empires as the British and French were themselves, although American films set in the French and British empires

BOLLYWOOD

The roots of India’s Mumbai-based cinema industry, informally known as Bollywood, stretch back to July 7, 1896, when the Lumiere Brothers showed six silent short films at a Bombay hotel. However, Dhundiraj Govind Phalke (Dada Saheb Phalke) has been recognized as setting the industry in motion with the production of Raja Harishchandra. Introduced in Bombay on May 3, 1913, this film was the country’s first totally indigenous silent feature. Silent films soon proved popular, in part because they provided entertainment that transcended the barriers to communication created by India’s great diversity of languages.

A formal film industry structure emerged in Bollywood during the 1920s, and by the 1930s the organization of India’s cinema industry very much resembled the manner in which Hollywood was organized in the United States, with studios directly employing actors and directors. This structure eventually changed due to the influence of independent producers.

Silent films quickly gave way to pictures with sound during the early 1930s. The Imperial film company released Alam Ara, India’s first “talkie,” on March 14, 1931. In addition to creating indigenous language barriers, talkies also isolated India from Western films, allowing Indian films to flourish. A number of productions that addressed social injustice were produced during the 1930s, and the industry continued to create significant films during the 1940s.

The 1950s marked the so-called “golden age” of Bollywood. As the Economist noted in its September 15, 2001, issue, in a review of Nasreen Munni Kabir’s book, Bollywood: The Indian Cinema Story: “Back in the 1950s film makers such as Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor, and Guru Dutt rode on a wave of intellectual dynamism that had been whipped up by the raising of the Indian flag at independence. These directors were happy to take on realistic themes, such as caste, morality and the place of women in a fast-changing world.”

During the 1960s color films emerged, and Bollywood began to concentrate heavily on the production of escapist, romantic pictures. Some have characterized the Indian films of this decade as being produced mainly with box office receipts and distributors in mind. Directors like Ritwik Ghatak, Satyajit Ray, and Mrinal Sen pioneered the New Indian Cinema in reaction to such films, by focusing on the production of more artistic pictures with social significance.

During the 1970s big-budget Bollywood productions tended to focus on the themes of action and revenge, even as New Cinema productions continued to be released. Some have argued that Bollywood reached an all-time low during the 1980s, which they see as an era marked by films of poor quality. After declining in number during the 1970s, roles for female actresses virtually disappeared. The 1990s saw a trend toward “glamorous realism,” which brought a return to romantic films and the reemergence of strong roles for female actresses. In addition, the introduction of satellite and cable television created new entertainment options and new venues for music drawn from Indian films.

By the early twenty-first century, Bollywood had produced, since its humble origins, roughly 27,000 feature films and many more short films. Bollywood continues to produce more than 100 films per year. were often more attuned to non-European sensibilities. In 1916 Hollywood made Anatole France’s novel Thais (1890) into The Garden of Allah (dir. Colin Campbell). This story about very little, a man and a women abandoning their religion and seeking their selves in the North African desert, was remade in 1927 (by Rex Ingram) and in 1936 (by Richard Boleslawski) in the United States, apparently because of the popularity of the exoticism and romance of the desert.

The Sheik (1921), the film that made the Italian-born actor Rudolph Valentino (1895-1926) a star, involves a London socialite traveling across the Sahara, where she is attacked by bandits. She is rescued by Sheik Ahmed Ben Hassan (Valentino), and the English lady and the Arab sheik fall in love. North Africa also served as the setting for Beau Geste, an adaptation of a British story about three English Geste brothers and the French Foreign Legion. This story, set in French North Africa, highlighted the virtues of English and French manliness and brotherhood in the context of relentless Arab attacks.

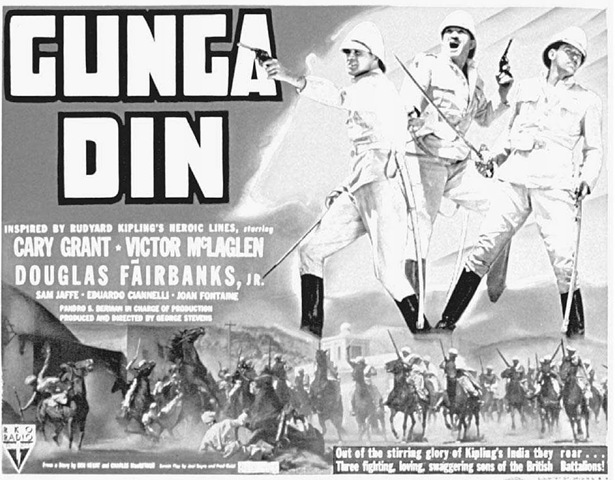

The 1930s became the golden age of British colonialism in Hollywood and the classic action-adventure spectacular. Henry Hathaway’s The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1934), a blockbuster success in America and Britain, is a melodrama about three British officers stationed in northwest India. This film set the civilized British soldiers against the ruthless and treacherous Afghan rebel Mohammed Khan, who tortured well-bred Englishmen. The success of Bengal Lancer brought more films like it: Clive of India (dir. Richard Boleslawski, 1935), Storm over Bengal (dir. Sidney Salkow, 1938), The Sun Never Sets (dir. Rowland Lee, 1939), Gunga Din (dir. George Stevens, 1939), and Stanley and Livingston (dir. Henry King, 1939).

Gunga Din Poster, 1939. Gunga Din, director George Stevens’s take on Rudyard Kipling’s smug commemoration of a loyal Indian water-bearer, portrays British soldiers as brave and heroic.

Gunga Din, George Stevens’s (1904-1875) take on the British author Rudyard Kipling’s (1865-1936) smug commemoration of a loyal Indian water-bearer, naturally portrays the British soldiers as brave and heroic. However, the anti-British enemy is noted to be lovers of ”Mother India” and therefore not mindless fanatics but believers in a worthy cause. Kipling’s multicultural theme, and the one often pushed by liberal American filmmakers, was found in the story of Gunga Din, who was a nobody and who in the end sounded his bugle, warned the troops, rescued his friends, and saved the day.

Prior to World War II, French, British, and American films rarely deviated from the accepted values and norms of their times regarding the framework of colonialism. Filmmakers took the dichotomy of civilized settlers and primitive natives for granted. However, not all films on colonial subjects followed these rules. The disintegration and liberation of the European colonial empires in the decades following 1945 transformed the way the West understood colonialism and therefore changed cinema’s view of colonialism. This change did not happen immediately. King Solomon’s Mines (dirs. Compton Bennett and Andrew Marton, 1950, a remake of the 1937 British film), Storm over Africa (dir. Lesley Selander, 1953), West of Zanzibar (dir. Harry Watt, 1954), Zulu (dir. Cy Endfield, 1963), and Khartoum (dirs. Basil Dearden and Eliot Elisofon, 1966) continued to portray the British colonial soldier or adventurer as the noble agent of “civilization.” The story of how Muhammad Ahmad, the Mahdi, an Islamic mystic, organized an army and drove the British out of the Sudan in 1885 is told in Khartoum. British General George Gordon (1833-1885), martyred in the campaign, was played by the handsome and heroic American actor Charlton Heston. The British actor Laurence Olivier, as the Mahdi, on the other hand, presented a lunatic religious fanatic, an Islamic stereotype that was reinforced in later movies from time to time.

By the 1960s, with the demise of most of the European empires, Western filmmakers had begun their passage into cinematic collective guilt, cultural self-condemnation, and moral instruction. La bataille d’Alger (The Battle of Algiers, 1966), an Italian film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo (b. 1919) about the anticolonial uprising against French colonialism in the capital of Algeria from 1955 to 1957, brought the bitter history of colonialism and anticolonialism to life in French cinemas and everywhere else. This documentary-style film won awards in Venice, London, and Acapulco largely because of its obvious political perspective, a defense and justification of the National Liberal Front (FLN), the Algerian insurrectionary organization. Bosley Crowther, writing the review for the New York Times, observed that Pontecorvo’s film was essentially about valor, “the valor of people who fight for liberation from economic and political oppression. And this being so, one may sense a relation in what goes on in this picture to what has happened in the Negro ghettos of some of our American cities more recently” (Crowther 1967/2004, p. 82).

French audiences, along with other Europeans and Americans, were outraged by the provocations, torture, and killings that The Battle of Algiers attributed solely to the colonial police and the French army. The terrorism of the FLN is explained by the planting of a bomb by the police in a crowded apartment building. Although the police and the army committed many abuses and crimes in the war, this particular event was a fabrication of the filmmaker. The insurrection began in August 1955 when the FLN launched a campaign to murder every French civilian and official in the country. FLN death squads killed men, women, and children, and immediate French reprisals led to mass arrests and more murders. This war, a bloodbath of atrocity and reprisal that began in 1955 and continued until the cease-fire of 1962, killed more than eighty thousand French settlers and soldiers and many hundreds of thousands of Muslim Algerians. Neither The Battle of Algiers nor the more commercial American film Lost Command (dir. Mark Robson, 1966) provided any kind of nuanced or even historically reliable and complete picture of this tragic war.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the sins of European colonialism were being compounded with those of the American war in Vietnam in British and American films. Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), a film about the British war against Russia in the Crimean Peninsula in the 1850s, abandoned the heroics of both the 1854 poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) and Michael Curtiz’s 1936 American film on the same subject. In Richardson’s version, the doomed Light Brigade is a symbol of everything wrong with Victorian England: jingoism, elitism, ideological blindness, and strategic bungling.

Zulu Dawn (dir. Douglas Hickox, 1979), the pre-quel to 1964′s Zulu, depicted the Battle of Isandhlwana of 1879, which was the worst defeat of the British army in Africa. This anti-British epic contrasted the peaceful yet heroic Zulu (as suggested by the title) with the arrogant and stupid British. Director Hickox (19291988) and screenwriter Cy Endfield (1914-1995) compared the British in Africa to the Nazis. Prior to the British invasion of Zululand, the colonial governor is made to say, “Let us hope that this will be the final solution to the Zulu problem” (quoted in Roquemore 2000, p. 373).

American westerns by the 1970s presented the white man as the savage antihero and the Indian as the respectable and courteous husband, brother, citizen, and leader. Little Big Man (1970), directed by Arthur Penn (b. 1922), tells the story of Jack Crabb, the sole survivor (perhaps) of George Armstrong Custer’s “Last Stand” in the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory. Penn demystifies a vain and neurotic Custer and sadly allows the audience to see the extinction of the Cheyenne (who call themselves ”human beings”) through the story and eyes of Jack.

The propagandistic Soldier Blue (dir. Ralph Nelson, 1970) focused on the U.S. Cavalry’s 1864 Sand Creek massacre in Colorado. The murderous glee of most of the racist soldiers was reflected in the outrage of the one appalled hero. This film, like Little Big Man, made visual references to the Vietnam War and American ”atrocities,” such as the infamous My Lai massacre of March 1968. The ultimate triumph of this cinematic revisionism was Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990), a three-hour epic about the Lakota Sioux that portrayed the Indians as peaceful, sophisticated, and above all civilized people in contrast to the violent, incompetent, and barbaric white soldiers. This beautiful atonement for Hollywood’s too many ”Injun” insults won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The ”evils of civilization” and the ”conquest of paradise” themes continued to be explored through fabulous cinematography 1492: Conquest of Paradise (dir. Ridley Scott, 1992) and The New World (dir. Terrence Malick, 2005).

One of the most important themes in colonial studies, as well as in colonial films, is the allure of the “other” or the exotic, that is, the attraction or enticement of colonial culture and the temptation of “going native.” The usual or “normal” assumption that the other culture is offensive, savage, unsophisticated, and generally uncivilized is reversed when a hero or heroine adopts not only the outward signs and customs of the foreign and colonial culture, but in the most personal, physical, and emotional manner “becomes” the other. We see this with Costner’s Lieutenant John Dunbar, who easily abandons his soldierly, white, and American identity in order to become “Dances with Wolves,” the husband of “Stands with a Fist” and a member in good standing of one band of the Lakota Sioux.

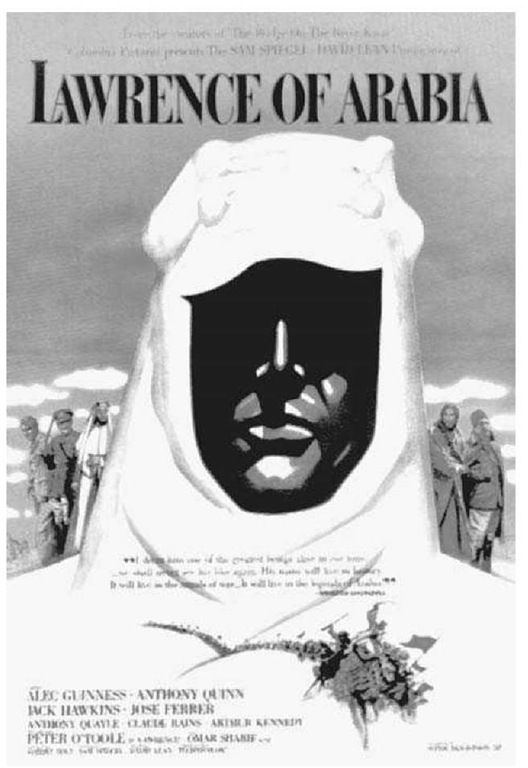

One of the classic films of British colonialism, indeed one of the classic films of all time, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962), is the story of an eccentric British officer, T. E. Lawrence (1888-1935), who joined forces with Arab tribesmen during World War I and became a legendary man of the desert. Peter O’Toole’s Lawrence was, like his Arab allies, a magnificent warrior, both courageous and enigmatic. Lean also shows Lawrence as the fallible westerner, whose good intentions for Arab independence allowed his confidence to turn into arrogance and bloodlust. Although Lean and scriptwriter Robert Bolt had no difficulty presenting the Turks as vicious enemies, their portraits of the Arabs were as attractive yet indistinct as the desert cinematography. The vain and weak Prince Feisal who led the tribes of the peninsula was played by Alex Guinness as cagey, educated, and wise.

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed a new wave of what would generally be called rich and complex colonial stories in the movies. Not since the 1930s had English-speaking movie houses seen so many colonial stories about India and Africa. Staying On (dir. Silvio Narrizzano, 1981), Heat and Dust (dir. James Ivory, 1982), Gandhi (dir. Richard Attenborough, 1982), A Passage to India (dir. David Lean, 1985), Out ofAfrica (dir. Sydney Pollack, 1985), The Mission (dir. Roland Joffe, 1986), Dien Bien Phu (dir. Pierre Schoendoerffer, 1991), Indochine (dir. Regis Wargnier, 1992), L’Amant (The Lover, dir. Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1992), and the 1984 British television series The Jewel in the Crown were beautiful, passionate, and popular films about colonial relationships. In most of these films, the nature of colonialism and the colonial relationship is viewed from the perspective of a European. In Indochine, for example, French colonialism in Vietnam from the 1930s to the 1950s is seen through the eyes and experience of a privileged daughter of a rubber plantation owner, Eliane de Vries (played by the French actress Catherine Deneuve). When Eliane adopts a Vietnamese orphan and is radicalized by the Communist revolution, the audience is taken on the journey of anti-French sentiment that pushed the Vietnamese into rebellion, revolution, and the war against the French.

Lawrence of Arabia Poster, 1962. One of the classic films of British colonialism, Lawrence of Arabia depicts T. E. Lawrence as the fallible westerner, whose good intentions for Arab independence allowed his confidence to turn into arrogance and bloodlust.

The rest of the world—North Africans, Arabs, Latin Americans, Africans, Indians, Asians, and others—have been making films since the beginning of filmmaking. French-Moroccan filmmakers in the 1920s and 1930s made dozens of quality films about contemporary life and history. In many parts of the world, and not simply in colonies, early filmmaking was the result of joint productions between Europeans and locals. States created national studios to support local directors and screenwriters and to finance national productions. In Algeria, for example, the newly independent revolutionary state set up Casbah Films in 1962, led by Yacef Saadi, which coproduced The Battle of Algiers. By the 1950s and 1960s, films from the so-called third world, such as Bharat Mata (Mother India, dir. Mehboob Khan, 1957) from India and Bab El Hadid (Cairo Station, dir. Youssef Chahine, 1958) from Egypt, were becoming recognized around the world.

Colonial themes have appeared in many films from the third world, although, perhaps surprisingly, this topic has never been dominant. In the non-Western cinema, as in the West, filmmakers and audiences are drawn to a wide variety of stories. Films on colonialism from the third world, like those from the West, can be divided into two groups: the many films that feature nationalist and politicized lectures on the evils of colonialism, and the fewer eloquent stories that reveal the weakness of the seemingly strong empires and the strength of the apparently oppressed people. Satyajit Ray (1921-1992), India’s best-known director, took the second approach in Shatranj Ke Khiladi (The Chess Player, 1977). The French-Egyptian production Al-Wida’a ya Bonaparte (Adieu Bonaparte, dir. Youssef Chahine, 1985) is an intimate focus on Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1798 Egyptian campaign; the film translates colonial relations into the homosexual love affairs of a Frenchman and two Arab brothers. Private dramas acquire political dimensions that, given the context of colonialism, alter even the best intentioned of human contacts.

The movie Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India (dir. Ashutosh Gowariker, 2001), a nearly four-hour period film set in 1893, is a masterpiece from Bollywood (the Bombay-based Indian film industry) by Bombay’s hottest movie producer and actor, Aamir Khan. Set in the little village of Champaner near a British cantonment, the villagers discover that they must pay twice the amount of lagaan (land tax) because the local Indian prince does not eat meat. The arrogant British officer in charge demands complete obedience but is willing to make a bet: The soldiers will play a game of cricket with the villagers (who have never played the game). If the villagers lose, they must pay triple the tax. Khan, playing a young farmer, organizes the village and obtains the support and instruction of the British officer’s sister. What starts out as a gesture of pity evolves into an exotic love story. In the end, naturally, the simple villagers triumph over the sophisticated British at their own game, the weak beat the strong, and the oppressed obtain justice.

Although they had many opportunities, Khan and Gowariker did not paint the Indian villagers and the British soldiers with the broad ideological brush strokes that even the best filmmakers have been known to use, as can be seen in The Mission, Dances with Wolves, 1492: Conquest of Paradise, and The New World. In Lagaan, both villagers and British soldiers are portrayed as people, people with their particular problems and flaws. The audience is inspired by the villagers’ spirited efforts to build a cricket team, but also grateful to the filmmakers for refusing to slip into the easy path of portraying the ordinary British soldiers as racist and violent monsters.

As is true with many Bollywood pictures, Lagaan is a musical filled with singing and dancing and is perhaps one of the best movies yet made about Western colonialism. It is mostly in Hindi, with subtitles in English. Other films may be more important—Lawrence of Arabia, Gandhi, The Rising (dir. Ketan Metha, 2005)— but Lagaan blends the serious and humorous, a love story and the love of sports, the imperial colossus and the peasant village in the middle of nowhere, and interesting stories of individual characters.

Perhaps the greatest historical epic film ever produced in India is Metha’s The Rising, a telling of the Sepoy Revolt of 1857 (called the ”First War for Independence” by Indians) against the British East India Company. This film concentrates on the life of Mangal Pandey, the sepoy who started the rebellion, who is played by Aamir Khan.

For students and teachers, scholars and readers, and movie fans and history buffs, the world’s filmmakers have offered many movies about colonialism, far more than can be touched upon in this short entry. The adaptation of this relatively new art form to the historic events, classic stories, great personalities, moral dilemmas, and personal relationships of Western colonialism has produced great film epics, exciting dramas, exotic romances, good and bad propaganda, and much more. In the early twenty-first century, filmmakers have new technologies and special effects, as well as more money, to produce epics, and they have barely touched many of the great stories of modern colonialism and empire.

The desire to see colonial cinema, from the filmmakers of Hollywood and Bollywood, from the studios of France, Britain, and Mexico, as well as Senegal, China, and Egypt, is a continuing and widening challenge, like finding and reading good and interesting colonial history and historiography. Cinephiles search video and DVD shops and now the Internet, looking for both the classic colonial movies and the lesser-known Western and non-Western films that have explored colonial themes. Scholars are researching how ”empire cinema constructed the colonial world” (Chowdhry 2001), and professors are teaching courses in colonial cinema. Nearly every university in the United States offers courses in film studies, and courses on films about Western colonialism are not uncommon. It is a great time to be watching colonialism at the movies.