1587-1629

Jan Pietersz Coen, twice governor-general of the Dutch East Indies, was born in the city of Hoorn, in the province of Holland, on January 8, 1587. Raised in a strict Calvinist environment, he received a commercial training in the firm of the Flemish merchant Justus Pescatore (Joost de Visscher) at Rome. In 1607 he entered the service of the Dutch United East India Company (VOC). Rising quickly through the ranks, in 1613 Coen was appointed bookkeeper-general of all company settlements in Asia and president of the VOC establishments at Banten and Jakarta in West Java. In 1614 he became director-general, the highest company official in Asia next to the governor-general. In April 1618 Coen was appointed governor-general by the board of directors, called the HeerenXVIIor Gentlemen Seventeen.

In 1614, even before he became governor-general, Coen had submitted a series of recommendations to the board of directors in his Discoers toucherende den Nederlantsche Indischen Staet (Discourse on the State of the Dutch East Indies). First, he advocated aggressive action against European competitors and indigenous rulers. Whereas his precursor, Governor-General Laurens Reael (1616-1619), had been cautious in the establishment of the spice monopoly as desired by the Gentlemen Seventeen, Coen had little consideration for the interests of the indigenous population. Second, Coen called for the settlement of Dutch colonists as ”freebur-ghers” in certain parts of company territory. These European settlers could subsist on agriculture, manufacturing, and trade (though only in less lucrative commodities not monopolized by the company). In case of emergency, the ”freeburghers” could also support the company militarily. Third, Coen urged the company to participate in the intra-Asiatic trade, and claimed that its profits could completely finance the purchase of commodities destined for Europe. Coen was particularly interested in the Chinese overseas trade. To achieve these goals, Coen called on the Gentlemen Seventeen to dispatch more capital and ships than they had done so far in order ”to prime the pumps.”

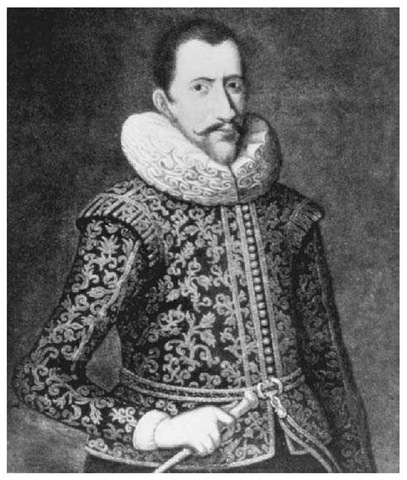

Jan Pietersz Coen. The governor-general of the Dutch East India Company during the early seventeenth century, shown here in an eighteenth-century portrait.

During his first term as governor-general (1619— 1623), Coen’s primary goal was to realize the company’s wish to establish a central administrative and commercial headquarters in Asia. At the time, Banten was the main commercial center on the island of Java. Relations with the local ruler of Banten, however, were tense, and competition with English and Chinese rivals fierce. Coen gradually moved more company goods to the warehouses at nearby Jakarta, where the VOC had had an establishment since 1610. In 1618 the English founded a trading post opposite the Dutch settlement. Coen responded to this ”affront” by fortifying the VOC establishment without the consent of the local ruler. Learning that the English had captured a Dutch ship, Coen had the English settlement razed to the ground. In the ensuing hostilities, the small Dutch garrison was able to maintain itself due to divisions amongst its Jakatran, English, and Bantenese rivals. Returning with a large relief fleet, Coen put the city of Jakarta to the torch. On its ruins rose like a phoenix the VOC capital of Batavia, soon known as the ”Queen of the East.”

The second item on Coen’s agenda was to attain a nutmeg and mace monopoly for the VOC. The Banda Islands in eastern Indonesia were the world’s sole production area. Exclusive agreements with the Bandanese, however, were not observed, partly because the company was unable to provide the inhabitants with sufficient food and clothing. Coen opted for the iron fist approach and in 1621 appeared with a large force in the Banda Sea. Following the capture of the islands, the entire population, an estimated 15,000 Bandanese, either perished—at the hands of the Dutch or through starvation—or were enslaved. The depopulated islands were divided into spice gardens, worked by European freeburgher ”gardeners” and slaves imported from elsewhere across the Indian Ocean basin.

Finally, Coen also had a shot at the China trade. By attacking Portuguese Macao and Spanish Manila, Coen hoped to redirect Chinese shipping to Batavia. Several blockades of Manila proved fruitless. An attack on Macao in 1622 ended in disaster, though a fort was established on the Pescadores off the Chinese mainland. The Chinese authorities, however, ignored Dutch demands concerning the junk trade. Company attacks against Chinese ships and coastal settlement proved counterproductive, and the VOC was forced to withdraw from the Pescadores to Taiwan.

At his own request, Coen returned to the Dutch Republic in 1623. He was feted and appointed company director of the Hoorn chamber. In a Memorie (Memorandum), Coen drew up regulations for trade by the Dutch ”freeburghers” in Asia, largely corresponding with the ideas he had first expressed in 1614. The Gentlemen Seventeen approved the memorandum and, duly impressed, successfully requested Coen to accept a second term as governor-general.

Coen’s second term as governor-general (16271629) was dominated by the two sieges of Batavia in 1628 and 1629 by the ruler of Mataram in the interior of Java. Having conquered the bulk of the island, Sultan Agung (r. 1619-1646) demanded Dutch assistance against or free passage of his forces across company territory en route to Banten. Coen rejected the demand, which led to two abortive sieges of Batavia. During the second siege, however, Coen suddenly died, probably due to cholera, on September 21, 1629.

Jan Pietersz Coen, initially admired as the founder of the Dutch colonial empire in the East, has more recently been vilified as ”the butcher of Banda.” Admittedly, the harsh policies of ”Iron Jan” were condemned even by some of his contemporaries. Coen’s ”grand design,” however, was largely in accordance with prevalent mercantilist thought. In general, the company’s board of directors, influenced by like-minded empire-builders such as the Rotterdam director Cornelis Matelieff, shared Coen’s oft-quoted maxim ”do not despair, and do not spare your enemies” {Dispereert niet, ontsiet uwe vyanden niet).