Apartheid (ap-ar-taed) is an Afrikaans word meaning “separation” or literally “apartness.” It was the system of laws and policy implemented and enforced by the “white” minority governments in South Africa from 1948 until it was repealed in the 1990s. As the idea of apartheid developed in South Africa, it grew into a tool for racial, cultural, and national survival.

While apartheid became official state policy only in 1948, its social and ideological foundations were laid by the predominantly Dutch settlers in the seventeenth century. Apartheid’s body of laws, arising from legislation passed in the years following the 1910 unification, helped define it as a legal institution enforcing separate existence for South Africa’s races. Not until the late 1980s did it crumble under pressure from international condemnation and Nelson Mandela’s appeal to freedom and democracy in South Africa. Nevertheless, the ultimately failed system was one many Afrikaners and Europeans in southern Africa believed in, and it is important to appreciate how this racial and cultural policy developed.

The arrival of the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC) at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 ushered in the first wave of colonial change for the region. As the relationship between Europeans and Africans developed, the VOC came to expect cooperation and subjugation from its Khoikhoi and Khoisan neighbors. Relations had been fairly equal at first, but a growing European population, as well as the requirements of foreign trade, increased demand upon the native Africans for resources, including the Khoikhoi’s prized cattle. This demand could not be met, and native ranchers who formerly held contracts with the company were forced into its service. In addition to cattle trading, cattle rustling also occurred on both sides, and the company began fencing off VOC property, physically separating itself from African neighbors and thereby introducing the first racial divisions. Africans were still allowed within company boundaries, but only if they were slaves or there to conduct business.

This process continued to intensify, and over time Africans found themselves increasingly dependent upon the VOC for survival. They adopted European customs and came to be dominated by European ideas and culture. Regardless of these changes and the fact that many settlers intermarried with the Khoikhoi, the Europeans did not consider the Africans to be equal. Moreover, these developing notions of apartheid were not limited to Euro-African relationships. The VOC could be a stern taskmaster. It expected its workers to labor strictly in the interest of company venture. Over time, however, some of the more entrepreneurial employees yearned for a life apart from their service to the VOC. They felt the urge to settle down and raise families, and while the company allowed them to develop plots of land beyond the company boundaries, the VOC vigorously sought to contract with them for agricultural products. The wealthier free-burghers, as these independent farmers were called, managed to win the choicest contracts, leaving their poorer neighbors distrustful of the VOC’s methods. Corruption among company officials, and the need to tax and administer the freeburghers, further inflamed tensions already growing between the two camps.

A Segregated Lavatory in South Africa. A group of men stand in front of a lavatory in apartheid-era South Africa with separate entrances for “European ” and “non-European” men.

Added to this were the cultural ramifications of the presence of a developing freeburgher community. As more employees and settlers arrived at the Cape, neo-Calvinism took root, enabling the VOC-recognized Dutch Reformed Church to build a local following. Cape Town had developed into a frontier community, with a varied population and myriad ideas. The more devout Calvinists were offended by a culture not aligned with the teachings of the church, and sought an existence separate from the debauchery of the growing town.

This moral conflict, combined with the Calvinist belief in a pure, divinely selected society, influenced many to leave. Administrative corruption also drove settlers out, and so the Cape settlement spun off new communities. One cannot understate the importance of this need to exist apart from the larger society. People were driven to create lives free from outside oppression in any form. Religion certainly played an important role, but so did this frontier mentality that space and opportunities were unlimited.

Britain’s arrival to the region only enhanced this dynamic culture of separateness. After revolutionary France aided Dutch liberals with the creation of the Batavian Republic, Britain moved to protect the Cape from republican Dutch and French annexation. The Cape was an ideal refueling stop on the way to India, and France’s acquisition of it would have been a strategic blow to Britain’s naval supremacy. Britain’s presence was only temporary, however, and the new administrators found it more efficient to maintain the established VOC methods of control. Britain quit the Cape in 1803 after making peace with France, but returned again in 1806 and established itself as the de facto power in the region. A formal assumption of control followed in 1814.

With its reappearance in 1806, Britain introduced its own administrative system, one that proved much more efficient than the VOC’s. Tax revenues increased, and as a result more settlers, or Boers (farmers), considered themselves to be at the mercy of an oppressive power. The British also introduced a circuit court system (the Black Circuit) that brought justice to the outlying regions, specifically to those settlers who had removed themselves from the confines of Cape Town. It also brought justice to the Africans, who began to bring suit against their employers for wrongdoing.

For many settlers, the circuit court was a violation of their rights. This violation was reaffirmed in 1815 when a farmer, Frederick Bezuidenhout, was charged with assaulting his servant. He resisted arrest and was shot. When his brother attempted to raise a rebellion, the British hanged him and four accomplices. For the Boers this British response was clear proof that they could not be trusted, especially as they had sided with the Africans. Such an act was impossible to fathom for a people who believed in racial purity and superiority. Already the British had aided the Xhosa in their ongoing wars with the Cape settlers. Now it appeared that the authorities were dispensing African justice.

It was in this way that the relationship between the Boers and the British developed throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Although many Boers left the Cape during the period of the Great Trek (1835— 1843), Britain’s reach extended into settlements in Natal and north of the Orange River. In the 1850s Britain recognized the establishment of the two Boer republics of the Orange Free State and Transvaal. This did not stop the British from meddling in Boer affairs, however, and by 1902 the opponents had fought two wars, the second of which (1899-1902) cost Britain over £200 million and opened a seemingly permanent rift between the two cultures.

The Boers, by then known also as the Afrikaners, began to refer to a ”century of wrong,” citing ongoing British oppression, as well as the fresh wounds caused by the war and the British concentration camps. Once again, Afrikaner culture was threatened. However, the British government in Westminster recognized the danger in imposing harsh peace terms upon the Boers. The government wanted a peaceful empire. In addition to paying for the damage caused in the war, therefore, the British put off any discussion of African suffrage and civil rights until self-government was established. At that time, South Africans themselves could decide the suffrage question.

While the Cape maintained its theoretically colorblind franchise law, the Afrikaner territories opted for racial domination. Upon establishing the Union of South Africa in 1910 (a sovereign imperial dominion),

Afrikaners finally were in control of their own destiny. In the coming decades apartheid would become increasingly formalized. Its future depended upon the path that Afrikaner politics and culture would follow, and the 1920s and 1930s witnessed the battle between the moderates and the conservatives for state control.

Jan Smuts, a one-time Transvaal state attorney and commando leader, had become a great friend of Britain. As prime minister, Smuts favored a pragmatic state administration, choosing to work with the empire for the benefit of South Africa. More conservative Afrikaners believed a complete separation from Britain was essential, but the moderates held sway, and South Africa supported Britain in the two World Wars. Many of the conservatives, if not openly hostile to Britain, assumed a position of neutrality, although there were those who identified with National Socialism’s racial theories.

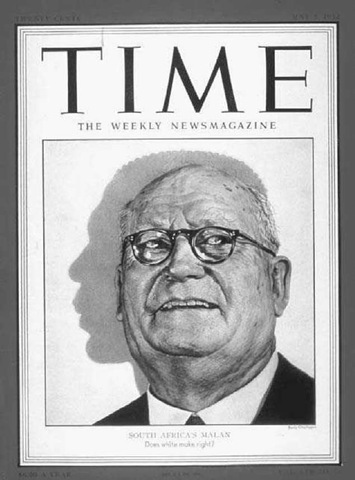

The moderation disappeared in 1948 when Daniel Malan’s Reunited National Party defeated Smuts’s government. Malan appealed to those Afrikaners who believed it was time that South Africa concentrated on its own development. Moreover, Smuts had loosened controls upon the flow of African labor to aid the war effort, and Malan now focused upon the evils of race mixing and the threat to a stable Afrikaner labor force. The new government formally enacted apartheid as state policy in 1948, and there followed a series of legislation targeting the non-white community.

Legislators envisioned a pure society, and drew on notions of unity and racial exclusivity when drafting new apartheid legislation. Laws promoting these principles were not new, for the 1913 Land Act stipulated who could and could not own certain lands. After the 1948 election, however, such legislation provided the new infrastructure of the Afrikaner state. The population was recategorized under the Population Registration Act of 1950, which spawned the issue of a new list of documents, and the creation of official, nationally recognized racial groups (White, Coloured, Asian, Bantu, and Others). With racial separation came physical separation as well, culminating in the Group Areas Act in 1950. The Group Areas Board identified zones based on race, clearing specific areas of families and entire communities for use by other groups. No longer would different races live in the same neighborhoods.

Movement between towns and cities had been required prior to the Abolition of Passes and Co-ordination of Documents Act (1952), but the new legislation mandated birth, residency, employment, marriage, and travel permits for all Africans. In 1953 the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act ensured that all services available to Afrikaners were also available to the other races. Although ”separate but equal” was the theory, the reality was a marked difference in the quality and cleanliness of amenities. This reality was made painfully obvious in the Bantu Education Act (1953). The government provided race-specific educational institutions, along with curricula designed to meet racial needs. In the Afrikaner state, necessary topics of study included Afrikaans and Christianity.

Daniel Francois Malan (1874—1959). Malan, the prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954 and one of the primary architects of the apartheid system, appeared on the cover of the May 5, 1952, issue of Time magazine.

Apartheid reached the epitome of its influence under H. F. Verwoerd’s leadership (1958-1966). As prime minister, Verwoerd pulled South Africa out of the Commonwealth, declaring the state a republic in 1961. He introduced the Homeland or “Bantustan” system, whereby the South African government recognized self-governing, and eventually fully independent, African states within the nation’s borders. Verwoerd took to heart the notion of separateness, and he preached a message of two streams of development, with the Afrikaner and African societies existing equally (in theory) and independently of each other. Often it was the less desirable land that comprised the newly independent African states. In 1971 the government completed the process with the

Black Homeland Citizenship Act, which rescinded homeland residents’ South African citizenship.

Although Verwoerd hoped that delegation of civil authority would free Afrikaners from managing millions of Africans, thereby helping to bring about that elusive, purely Afrikaner society, the Bantustans would serve to undercut the government’s power in the years to come. Moreover, Verwoerd’s death in 1966 signaled the beginning of apartheid’s slow decline. While the system still had another two decades of life, it was increasingly undercut by an emerging progressivism.

Apartheid’s peak in the 1960s coincided with the dissolution of European empires. The 1960s was the ”decade of independence,” and apartheid appeared increasingly as a tired, discredited system. Even as African colonies elsewhere in Africa prepared for sovereignty, the white South African government was arresting African nationalists, including Nelson Mandela, and trying them for treason. Nationalist organizations, such as the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), espoused socialism, reinforcing the National Party’s argument that it was defending the state against militant revolutionary elements. This was an effective argument in a society traditionally concerned with white domination of the labor market. That African nationalism had become an increasingly divided movement in the 1950s and 1960s only made the National Party’s job easier. The division, however, also forced a conversation among African nationalists, who began to hone their message in the 1970s.

Apartheid’s last hurrah came in the mid-1980s under P. W. Botha (prime minister, 1978-1984; president, 1984-1989). He wavered between a reluctant acceptance that the white-dominated state could not last in its current form, and a last-ditch battle to resurrect apartheid’s exclusive culture. Botha faced Afrikaner liberals, African nationalists, and foreign governments on the left, and disenchanted reactionaries on the right. The latter were leaving the National Party to join the Conservatives. Botha held the advantage in the mid-1980s, however, for African nationalists continued to face internal divisions over their movement’s direction. Moreover, homeland leaders wanted nothing to do with African nationalism, because it threatened their sovereignty within apartheid South Africa. As the ANC attempted to undercut its opposition, Botha imposed a state of emergency in 1985 to contain a growing African insurgency. Boycotts and work stoppages had the desired effect, however, and, combined with the power of foreign sanctions, began to bring about the collapse of the apartheid government.

President F. W. de Klerk (president, 1989-1994) replaced Botha in 1989 and attempted to introduce limited reforms to improve conditions for minorities without removing Afrikaners from positions of power. Negotiations with the ANC proved that approach to be unrealistic, and de Klerk found himself forced by internal and external pressure to release Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990. As Paul Kruger symbolized the Boers’ steadfastness, so did Mandela personify the African struggle. It was Mandela and the ANC, and not de Klerk, who had the political momentum. The last vestiges of apartheid crumbled as the ANC guided the terms of the negotiations. Mandela was both adept and reasonable, seeking not to punish the Afrikaners, but rather to enable Africans to assume their rights as the majority population. Mandela’s election to presidency in April 1994 sealed the fate of apartheid.

Although it is identified with white oppression in South Africa, apartheid also defined the Afrikaner struggle to maintain racial and cultural purity in a harsh land. The Boers competed with everyone, even themselves, to live the life in which they believed.