The first Afrikaner(s) were settlers, mainly of Dutch origin, who established themselves in the Cape of Good Hope region. Their descendants controlled South Africa for a long time and were the architects of the racist system that prevailed there until the 1990s. Initially, the Afrikaner were known as Boers, a word that means “farmer,” “peasant.” The Afrikaner speak Afrikaans, a language derived from Dutch with some contributions from German and French, the latter a legacy of the Huguenots who sailed to Africa in the seventeenth century to escape Europe’s religious wars. Traditionally, the great majority of Afrikaner have been members of the Dutch Reformed Church, one of the pillars of Afrikanerdom. Afrikaner identity was formed through a gradual indigenization that dissolved connections with the former motherland: hence the choice to use terms for themselves and their language that signaled that their destiny as individuals and a nation was rooted in Africa.

BEGINNINGS

The first Dutch community in the Cape was set up by the Dutch East India Company in 1652 under the command of Jan van Riebeeck, who was instructed to build a fort and a resupply station for ships traveling to and from Batavia (present-day Indonesia), the headquarters of Dutch possessions in Asia. In principle there was no intention to establish a colony, but increasing food needs and the favorable climate pushed settlers to farm and occupy more land. While extending settlements and spreading farther afield, the Boers encountered the communities of Bantu-speaking farmers. Much more developed and intimidating than the Khoikhoi and San—cattle-breeders and hunter-gatherers living in the region around the Cape, whom the Afrikaner had easily outnumbered—the Bantu formed a barrier to further Afrikaner expansion. The eighteenth century saw warfare on the border of Afrikaner-controlled territory that precariously divided whites and blacks. The Afrikaner expanded their possessions across the Fish River at the expense of the southern Nguni (Xhosa). Because the metropolitan power was far away and its representatives almost absent, the Boers developed a unique culture centered on independence, patriarchal authority, and firm hierarchization (the agricultural economy was based on slave labor and most of the servants, artisans, and laborers were slaves). They believed themselves to have been charged with a semi-divine duty to civilize Africa. The turning point in the history of the Afrikaner was the occupation of the Cape by the British during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1806 Britain replaced Holland as the colonial power and nine years later the occupation of the Cape was ratified at the Congress of Vienna.

THE GREAT TREK

Despite their common European background, rural Dutch and urban English settlers were separated by a cultural divide. This was bound to have great political significance. The British were not willing to let the Afrikaner manage their affairs autonomously and shaped the institutions of the country in a way that the Afrikaner found odious and untenable. The abolition of slavery was the final affront to Afrikaner habits. In order to escape obtrusive British administration, the Boers decided to resettle outside the colonial boundaries. The massive emigration northeastward that resulted, carried out in organized groups with ox-driven wagons, is known in Boer mythology as the Great Trek. It is conventionally dated to 1838. The Boers’ aim was to establish a new motherland. After battling and expropriating resources from the black tribes they encountered, the Voortrekkers founded two republics: the Transvaal or South African Republic (with Pretoria as the capital city) and the Orange Free State (with its capital in Bloemfontein). In the iconology of the civil religion constructed by Afrikaner, the Great Trek was the revolution: the liberation from British imperialism and the advent of a new nation.

However, Cape authorities and arch-colonial lobbies both in Britain and in Africa were determined to wipe out the Boer republics, daringly founded in a region under the paramount influence of the British. The conventions British emissaries signed with the Transvaal Voortrekkers in 1852 and with the representatives of the Free State in 1854—the latter a formal recognition of Afrikaner independence—were just a postponement of the unavoidable collision, ultimately precipitated by the discovery of the diamonds of Kimberley and of the immense gold fields in the Witwatersrand (Transvaal). In 1870 the European population of the territories occupied by the Voortrekkers numbered about 45,000. The republics’ autocratic regime was soon seriously challenged by an industrial and urban boom and by the flood of cosmopolitan Europeans in search of fortune. The British backed the claims of foreigners (Uitlanders) over the franchise and other rights of Afrikaners and thus caused a dispute with President Paul Kruger of Transvaal, champion of Afrikaner nationalism and inflexible warden of an anachronistic regime reserved for a pure elite of “founders.” The outcome was full-fledged war.

Hostilities erupted in 1899 after Kruger, wanting to act before the arrival of fresh troops from India and Europe, delivered an ultimatum to the British government. In spite of the resolute heroism of the Boer army and the Boer people in general (women and children were amassed in camps by the British in order to separate fighters from their family and social environment), British military forces succeeded in defeating the Boers. The Boer republics ceased to exist with the Treaty of Vereeniging, signed in 1902; Transvaal and Orange merged with the Cape Colony and Natal was absorbed into the South African Union under British control. The Anglo-Boer (or South African) War marked the end of the petty Boer nationalism personified by Kruger. It signaled the birth of a new Boer consciousness, one better suited to coping with development and modernity. The blacks, not the British, were now the enemy of the Afrikaner; for their part, the British accepted the revision or abrogation of the few rights enjoyed by black Africans as the price of ending the devastating war.

FROM APARTHEID TO DEMOCRATIC SOUTH AFRICA

The volk (the Afrikaner nation) survived the military catastrophe: in their self-conception, if the British were the colonial officials and owners of the mines, the Afrikaner were the authentic representatives of the soul of unified South Africa. The sophisticated and multifaceted apartheid regime—the system of racial segregation and discrimination imposed by the Afrikaner’s Nationalist Party after its victory in the 1948 elections—was a sort of apotheosis in the story of a people supposedly elected by God to carry out a very special mission in Africa. D. F. Malan was the first of a series of Afrikaner leaders (including H. F. Verwoerd, B. J. Vorster, P. W. Botha, and others) committed to creating Afrikanerdom by crushing or subduing black African aspirations to liberty, equality, and power. The British segment of South Africa’s white population never fully endorsed the rationale for this extreme form of racism (though racism as a system was significant to the growth of South African capitalism), but they were unable to or did not really want to combat apartheid. All the heads of government and state in South Africa were Afrikaner from 1910, when independence was proclaimed, up to Nelson Mandela in 1994, when apartheid was formally abolished. The year 1994 also saw the country’s first universal elections and the triumph of the African National Congress (ANC), the party that had built the antiracist movement by mobilizing black Africans and people of any race who rejected racism. After 350 years of colonialism, the ANC’s victory established majority rule for the first time in South Africa’s history.

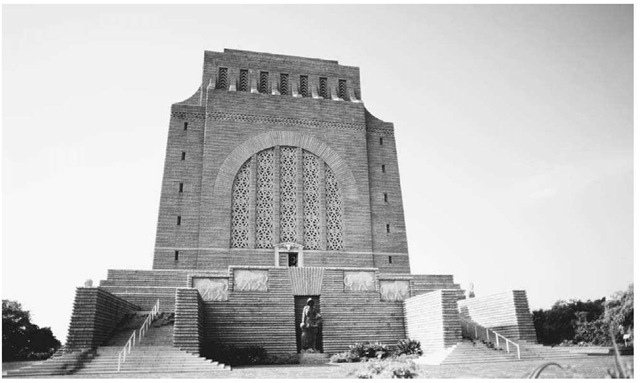

Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria, South Africa. Pretoria ‘s Voortrekker Monument, designed by Gerard Moerdijk and inaugurated in 1949, honors the original Afrikaner settlers of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State.