The African National Congress (ANC), the oldest black political organization in South Africa until it became multiracial in the 1990s, was founded on January 8, 1912, in Bloemfontein by chiefs, representatives of African peoples and church organizations, and other prominent individuals. The aim of the ANC was to bring all Africans together and to defend their rights and freedoms in a then racially divided South Africa.

The ANC was formed at a time of rapid change in South Africa. The organization began as a nonviolent civil rights group, but its tactics and strategy changed over time. The discovery of diamonds in 1867 and gold in 1886 transformed not only the social, political, and economic structure of South Africa, but the racial attitude of whites towards blacks. The contestations over mining rights, land, and labor gave rise to new laws that discriminated against the black population. Laws were designed to force Africans to leave their land and provide labor for the expanding mining and commercial agriculture industry. The most severe law was the 1913 Land Act, which prevented Africans from buying, renting, or using land except in the so-called reserves. Many communities or families lost their land because of the Land Act. Millions of blacks could not meet their subsistence needs off the land. The Land Act caused overcrowding, land hunger, poverty, and starvation.

The political activism of the ANC dates back to the Land Act of 1913. The Land Act and other laws, including the pass laws, controlled the movements of African people and ensured that they worked either in mines or on farms. The pass laws also stopped Africans from leaving their jobs or striking. In 1919 the ANC in Transvaal led a campaign against the passes. The ANC also supported a militant strike by African mineworkers in 1920. However, there was disagreement over the strategies to be adopted in achieving the goals set by the ANC. Some ANC leaders disagreed with militant actions such as strikes and protests in preference for persuasion, negotiation, and appeals to Britain. But appeals to British authorities in 1914 to protest the Land Act, and in 1919 to ask Britain to recognize African rights, did not achieve these goals.

In the 1920s, government policies became harsher and more racist. A color bar was established to stop blacks from holding semiskilled jobs in some industries. The ANC did not achieve much in this era. J. T. Gumede (1870-1947) was elected president of the ANC in 1927.

He tried to revitalize the organization in order to fight these racist policies. Gumede thought that communists could make a contribution to this struggle and he wanted the ANC to cooperate with them. However, in 1930, Gumede was voted out of office, and the ANC became inactive in the 1930s under conservative leadership.

The ANC was very prominent in its opposition to apartheid in the 1940s. The formation of the ANC Youth League in 1944 gave the organization new life and energy, and transformed it into the mass movement it was to become in the 1950s. The leaders of the Youth League, including Nelson Mandela (b. 1918), Walter Sisulu (1912-2003), and Oliver Tambo (1917-1993), aimed to involve the masses in militant struggles. They believed that the past strategy of the ANC could not lead to the liberation of black South Africans.

The militant ideas of the Youth League found support among the emerging urban black workforce. The Youth League drew up a Programme of Action calling for strikes, boycotts, and defiance. The Programme of Action was adopted by the ANC in 1949, the year after the National Party came to power on a pro-apartheid platform. The Programme of Action led to the Defiance Campaign in the 1950s as the ANC joined with other groups in promoting strikes and civil disobedience. The Defiance Campaign was the beginning of a mass movement of resistance to such apartheid laws as the Population Registration Act, the Group Areas Act and Bantu Education Act, and the pass laws.

The government tried to stop the Defiance Campaign by banning its leaders and passing new laws to prevent public disobedience. But the campaign had already made huge gains, including closer cooperation between the ANC and the South African Indian Congress, and the formation of a new South Africa Colored Peoples’ Organization (SACPO) and the Congress of Democrats (COD), an organization of white democrats. These organizations, together with the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU), formed the Congress Alliance.

The Congress Alliance called for the people to govern and for the land to be shared by those who work it. The alliance called for houses, work, security, and free and equal education. These demands were drawn together into the Freedom Charter, which was adopted at the Congress of the People at Kliptown on June 26, 1955. The government claimed that the Freedom Charter was a communist document and arrested ANC and Congress Alliance leaders and brought them to trial in the famous Treason Trial. The government tried to prove that the ANC and its allies had a policy of violence and planned to overthrow the state.

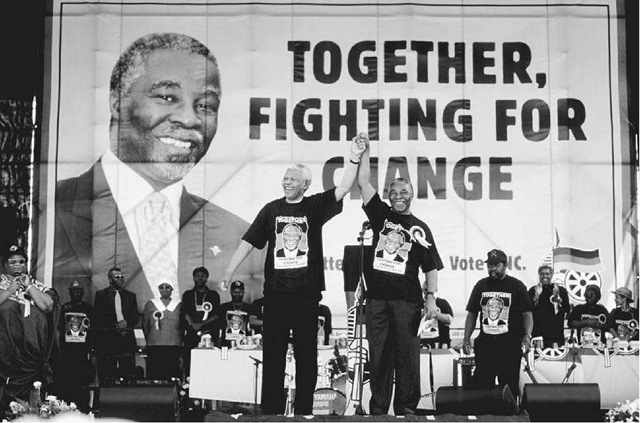

Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, February 28, 1999. South African president Nelson Mandela (left) stands with Deputy President Thabo Mbeki at a campaign rally in Soweto, South Africa. Mbeki succeeded Mandela as head of the ANC in 1997 and as president of South Africa in 1999.

The struggles of the 1950s brought blacks and whites together on a larger scale in the fight for justice and democracy. The Congress Alliance was an expression of the ANC’s policy of nonracialism. This was expressed in the Freedom Charter, which declared that South Africa belongs to all who live in it. But not everyone in the ANC agreed with the policy of nonracialism. A small minority of members, who called themselves Africanists, opposed the Freedom Charter. They objected to the ANC’s growing cooperation with whites and Indians, whom they described as foreigners. They were also suspicious of communists who, they felt, brought a foreign ideology into the struggle. The differences between the Africanists and those in the ANC who supported nonraci-alism could not be overcome. In 1959 the Africanists broke away and formed the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

Anti-pass law campaigns were taken up by both the ANC and the PAC in 1960. The massacre on March 21, 1960, of sixty-nine peaceful protestors at Sharpeville, near Johannesburg, brought a decade of peaceful protest to an end. The ANC was banned in 1960, and the government declared a state of emergency and arrested thousands of ANC and PAC activists. The following year, the ANC initiated guerrilla attacks. In 1964 its leader, Nelson Mandela, was sentenced to life in prison and the ANC leadership was forced into exile.

The ANC went underground and continued to organize secretly. An underground military wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe or Spear of the Nation, was formed in December 1961 to ”hit back by all means within our power in defense of our people, our future and our freedom.” The ANC continued to be popularly acknowledged as the vehicle of mass resistance to apartheid in the late 1970s and the 1980s. In spite of detentions and bans, the mass movement took to the city streets defiantly. In February 1990, the government was forced to lift the ban on the ANC and other organizations and signaled a desire to negotiate a peaceful settlement of the South African problem.

At the 1991 National Conference of the ANC, Nelson Mandela, who was released from prison in 1990, was elected ANC president. Oliver Tambo, who served as president of the ANC from 1969 to 1991, was elected national chairperson. The negotiations initiated by the ANC resulted in the holding of South Africa’s first democratic elections in April 1994. The ANC won these historic elections with over 62 percent of the votes. On May 10, 1994, Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the president of South Africa. Thabo Mbeki (b. 1942) succeeded Mandela as head of the ANC in 1997 and as president of South Africa in 1999.