1930-

Born on November 16, 1930, in Ogidi (southeastern Nigeria), Albert Chinualumogu (Chinua) Achebe is one of Africa’s best-known writers. Isaiah Okafor Achebe, a Church Missionary Society catechist, and his wife, Janet, named their fifth child Albert, after Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria. In college, Albert dropped his ”Christian name” for his Igbo name, Chinualumogu (”may God fight for me”)—Chinua, for short. He became a fighter himself through his writings—fighting to rectify the distortions in colonial narratives of Africa and her peoples in the works of writers such as Joyce Cary and Joseph Conrad; and fighting to expose and challenge what is wrong with postcolonial Nigeria—specifically, the failure of leadership.

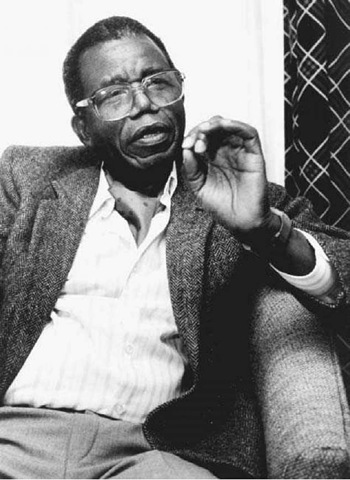

Chinua Achebe. One of Nigeria’s best-known authors, Achebe established an international reputation with his 1958 novel Things Fall Apart, which explores Nigeria’s response to British colonialism during the late 1800s.

Chinua Achebe’s long, brilliant career includes many years in broadcasting, teaching, publishing, and creative writing. Rejecting the art for art’s sake school of thought, Achebe insists that art has social value and function and the artist has a role to play in social change. He sees the writer as a teacher, moral voice, truth-teller, and social critic (Morning Yet on Creation Day, Hopes and Impediments, and The Trouble with Nigeria), and as a storyteller and a guardian of the word and memory (Anthills of the Savannah).

A versatile writer who has published short stories, essays, and poetry, Achebe is best known for his novels, which are written with a simplicity that is both elegant and poetic. Achebe’s first and best-known novel, Things Fall Apart (1958)—which takes its title from W. B. Yeats’s ”The Second Coming”—is set in an Igbo village of the late 1800s and captures the violence, disruption, and humiliation of colonialism. It posits the inevitability of change in cultural encounters, and argues for the necessity to negotiate and reconcile with change. His second novel, No Longer at Ease (1960), continues to probe the consequences of cultural collision and conflict, particularly the dilemma, ambiguity, and contradictions faced by those at the crossroads of cultures.

Achebe is a wordsmith for whom the use and abuse of language is a central concern. Not surprisingly, he joined the language question debates that exploded in African literary circles four decades ago. Disagreeing with those who insist that African writers write in indigenous languages, Achebe advocated the use of colonial languages, but in such a way that they are able to carry the weight and force of the African landscape, worldview, and imagination.

At seventy-four, Chinua Achebe speaks with the same moral clarity and writes with the same force and consistency as he did over four decades ago, when his first novel contributed to set the stage for what we know today as postcolonial literature. In 2004 Achebe was awarded Nigeria’s second-highest honor, but in an open letter to the Nigerian president, Achebe turned down the honor in protest: ”I write this letter with a heavy heart. … Nigeria’s condition today under your watch is, however, too dangerous for silence. I must register my disappointment and protest by declining to accept the high honor awarded me.”