The zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL)

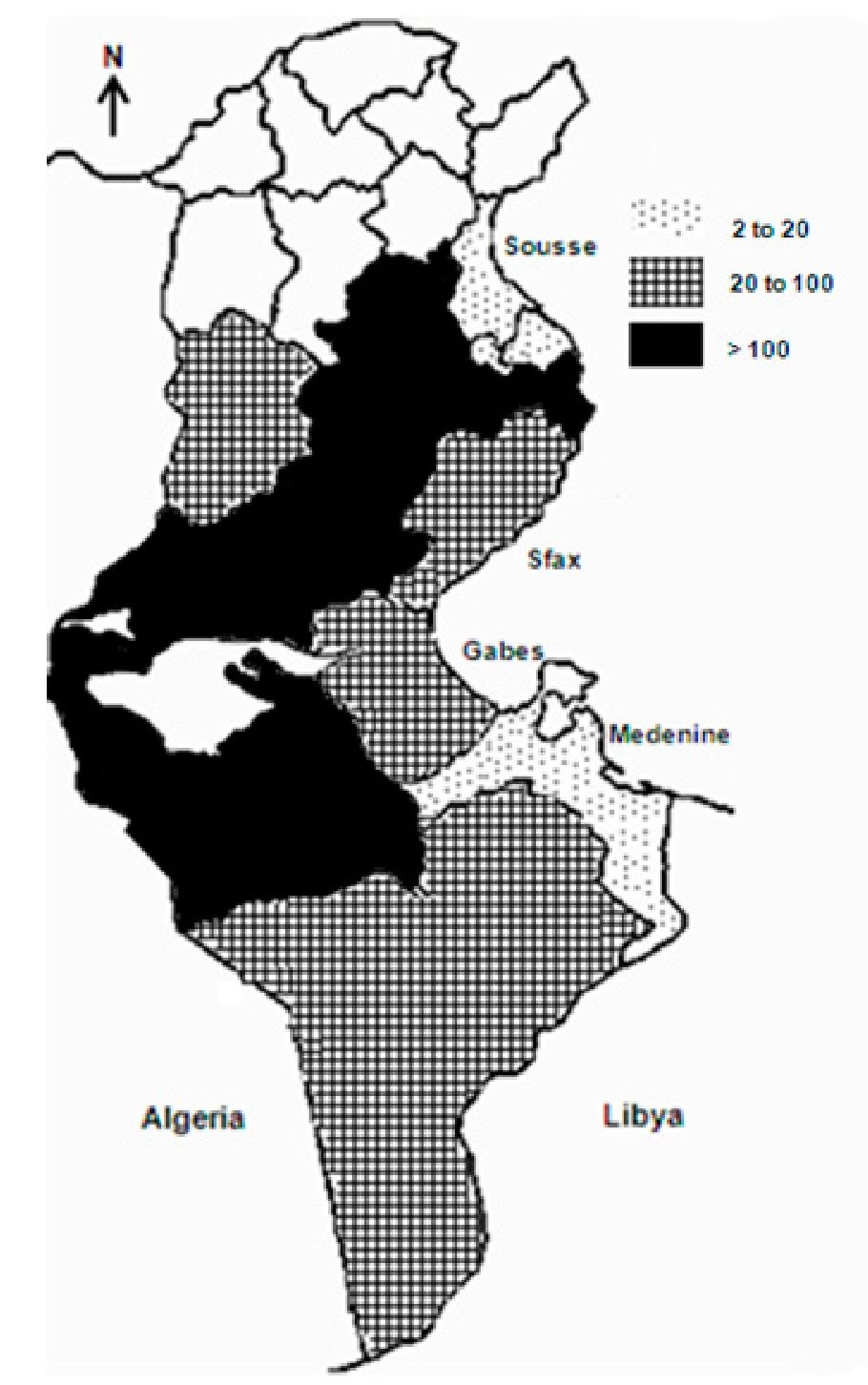

ZCL is by far the most frequent and the most widely distributed form of CL in Tunisia where it constitutes a major public health problem. It is endemo-epidemic in extended areas of central and southern Tunisia (Figure 5). It is caused by L. major and transmitted by the zoo-anthropophilic Phlebotomus papatasi sandfly which is mainly encountered and caught in and around the rodent burrows, and less in and around human habitations (Ben Ismail et al., 1987b, 1987c; Ben Rachid et al., 1992; Ghrab et a!., 2006; Helal et al., 1987). The reservoirs are rodents of the Psammomys and Meriones genera. The main one is P. obesus, a prolific diurnal rodent that is very abundant in arid and subsaharian areas. Its feeding requirements consist exclusively of chenopodiaceae (Salicornia, Salsola, Atriplex) that mainly grow in sandy, humid and salty soils unsuitable for agricultural purposes (Ben Ismail et al., 1987a; Ben Rachid et al., 1992; Fichet-Calvet et al., 2003). Psammonys infection rate may reach 100 %. The hygrophilic nocturnal rodents, Meriones shawi and Meriones libycus act as secondary reservoirs and are responsible of the spread of the disease because of their migratory habits. Meriones are granivorous and build their burrows in jujube trees (Zizyphus) surrounding cereal fields and often cause important agricultural damage (Ben Ismail & Ben Rachid, 1989; Ben Rachid et al., 1992). All Leishmania strains isolated so far from humans, rodents and phlebotomine vectors are of the zymodeme MON 25 (Aoun et al., 2008; Ben Abda et al., 2009; Ben Ismail et al., 1986; Haouas et al., 2007).

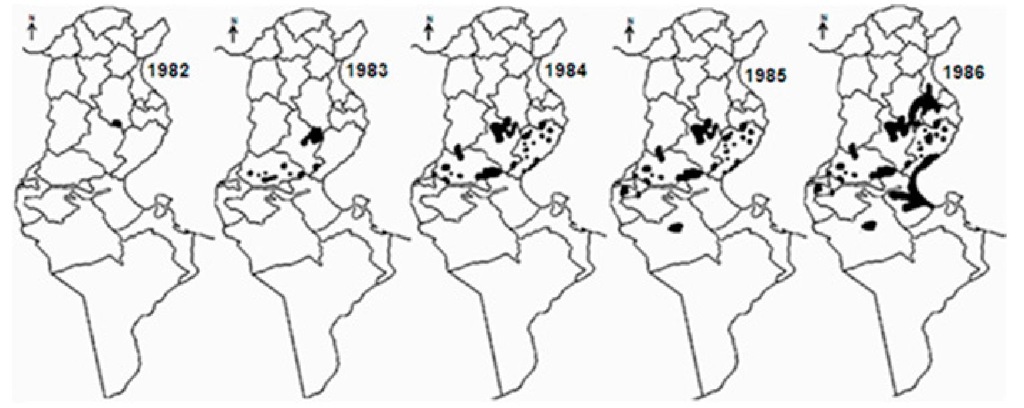

ZCL was first described in 1882 in and around Gafsa oases, and termed "clou de Gafsa" (Deperet & Bobinet, 1884). From this date and up to the beginning of the 20th century, many additional outbreaks were reported in the same area. Then, the disease continued to occur on a very sporadic mode, and nearly disappeared (Chadli et al., 1968; Vermeil, 1956). In 1982, a large outbreak arose in Nasrallah delegation (Kairouan governorate), near to the recently completed Sidi-Saad dam (Ben Ammar et al., 1984). From there, the disease rapidly spread to cover large rural and sub-urban parts of the central and south-western neighbouring governorates, so that, by 1986, 10 governorates were involved (Figure 6). In season 1991-1992, ZCL extended further south-east to Medenine and Tataouine governorates. All along the outbreak, Sidi Bouzid, Gafsa and Kairouan governorates have remained the leading areas in terms of incidence (Anonymous). However, from the early 1990s and up to date, Tataouine, Tozeur, Médenine, Kébili, Gabès, Sfax and Kasserine have emerged as active and stable foci (Figure 5). In the last few years, some level of ZCL spread towards the north (Siliana, Béja, Le Kef, Tunis and Zaghouan governorates) was registered, which is somewhat surprising (Ben Abda et al., 2009).

The number of annual recorded cases rapidly grew from 182 cases in 1982 to > 18000 cases by 1987, > 65000 cases by 1999. Up to date, > 120000 cases were reported and the epidemic is still going on. It should be mentioned however, that the actual number of cases is supposed to be underestimated and would exceed 150000 cases (Chahed et al., 2002). The number of annual recorded cases greatly varied and ranged from 1129 cases in 1995 to > 15000 in 2004, with an average of 4700 cases/year (Figure 7).

Fig. 5. Distribution of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis according to incidence ( expressed as 0/ 00 000).

The annual incidence showed the same fluctuations. It ranged between 3 0/ 00 000 in the less affected areas and > 500 in Kairouan, and > 1000 in Gafsa and Sidi Bouzid in 2004 (Anonymous). These fluctuations are at least in part related to the dynamics of rodents’ populations. It was demonstrated that the distribution of P. obesus is of paramount importance in the epidemiology of the human disease (Ben Ismail et al., 1987a; Ben Ismail & Ben Rachid, 1989; Ben Salah et al., 2007; Fichet-Calvet et al., 2003). On the other hand, control programmes are undoubtedly very effective and beneficial in terms of incidence. Indeed, a rodent control project, consisting of ploughing lands with growing chenopods and reafforestation with acacia and other plants was launched in 1992 in Sidi Bouzid city and suburbs that resulted in a dramatic decrease in the incidence of the disease in the area; but the intensity of the epidemic grew again as soon as the control programme stopped (Figure 7). From the mid 2000s, similar control measures have been carried out again in Sidi Bouzid and then in Sidi El Heni delegation which is the main transmission focus in Sousse governorate, and led to an obvious decrease of incidence in both foci.

The ongoing outbreak that started in 1982 near the Sidi-Saad dam may be explained by the interruption, as a result of the construction of the dam, in the flooding that frequently occurred in the area and used to decimate a high proportion of rodents every year. In addition, the enrichment of the area’s ground water helped the chenopodiaceae to grow abundantly, thereby increasing the food source of Psammomys. On the other hand, Atriplex, a plant grown in large quantities as a sheep fodder is much appreciated by Psammomys. Furthemore, humidity created by the dam is highly suitable for the sandflies.

Fig. 6. Spread of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis during the period 1982- 1986

Fig. 7. Annual number of reported zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis cases at the national level from 1982 up to 2010.

One of the characteristics of ZCL is its marked seasonal occurence as most cases are observed between october and january (Ben Ismail & Ben Rachid 1989; Ben Rachid et al., 1992). Clinically, ZCL most often presents as multiple, inflammatory ulcers on the face and the limbs that usually scar in less than 6-8 months, and affects all ages with a median of 24 years (Ben Abda et al., 2009; Ben Ismail & Ben Rachid, 1989; Chaffai et al., 1988; Masmoudi et al., 2007; Zakraoui et al., 1995).

Visceral leishmanasis (VL)

VL has been known to sporadically occur in Tunisia, since 1903 where the first case of mediterranean VL was described in a child living in the suburbs of Tunis. The disease is caused by Leishmania infantum, mostly zymodeme MON 1 and to a lesser extent zymodemes MON 24 and MON 80 (Aoun et al., 2001, 2008; Bel Hadj et al., 1996, 2000, 2002; Ben Ismail et al., 1986; Haouas et al., 2005; Kallel et al., 2008b). It is transmitted by Phlebotomus perniciosus sandfly, and the dog is the exclusive reservoir, with an infection prevalence rate ranging from 5% to 26 % (Ben Ismail et al., 1986; Ben Rachid et al., 1992; Bouratbine et al., 1998).

Since 1903, 2449 VL cases were reported in Tunisia (Table 2).

|

Period |

Nb cases |

Median/ year |

|

1903-1956 |

151 |

2.8 |

|

1957-1967 |

142 |

12.9 |

|

1968-1981 |

178 |

12.7 |

|

1982-1989 |

578 |

72.3 |

|

1990-2000 |

720 |

65.5 |

|

2001-2010 |

680 |

68.0 |

|

Total |

2449 |

22.7 |

Table 2. Number of visceral leishmaniasis cases reported in Tunisia (1903-2010)

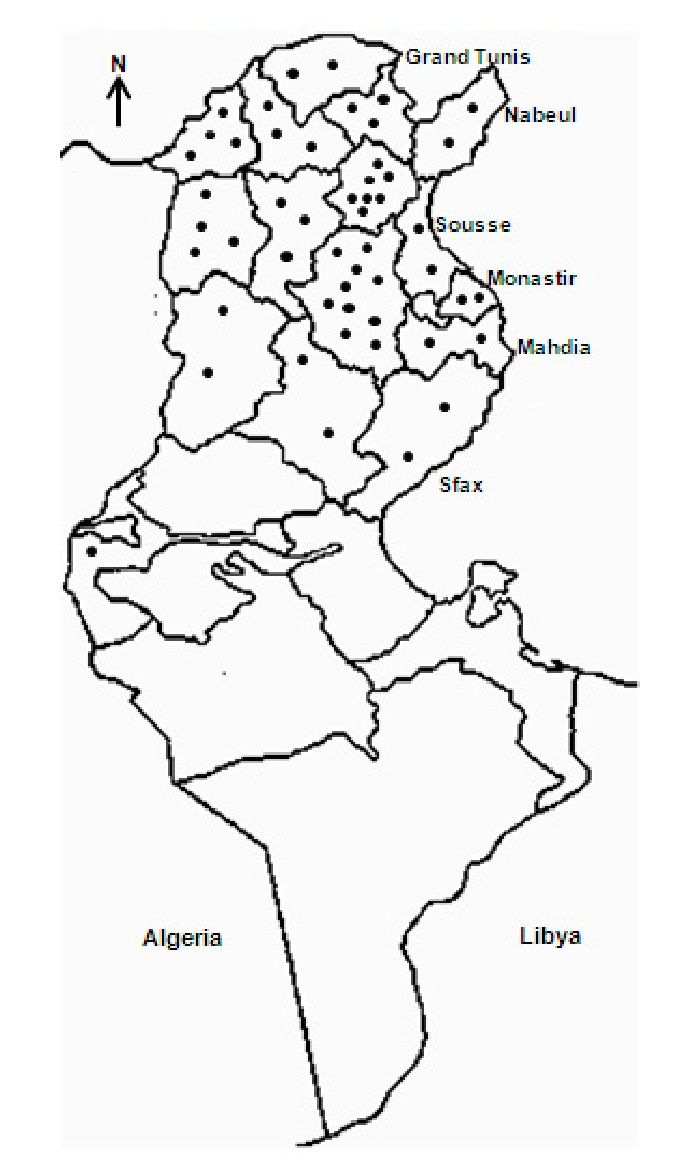

Up to 1981, incidence was low to moderate and nearly all cases were reported from Zaghouan, North-West (Le Kef, Béja, Jendouba, Siliana), Tunis and Sousse governorates, located in the humid, sub-humid and semi-arid zones (Anderson et al., 1934, 1938; Ben Ismail et al., 1986; Ben Rachid et al., 1983; Chadli et al., 1968; Khaldi et al., 1991; Nicolle, 1912; Vermeil, 1956). From the early 1980s, the incidence markedly increased and the disease progressed towards the south, mainly to Kairouan governorate and to a lesser extent to Sfax, Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine and Tozeur governorates, together with an increase in canine leishmaniasis (Ayadi et al., 1991; Bel Hadj et al., 1996; Ben Salah et al., 2000; Besbès et al., 1994; Bouratbine et al., 1998; Chargui et al., 2007; Pousse et al., 1995). Indeed, from the 1980s, the region of Kairouan emerged as a highly active VL focus, and by 1991-1992 it was recognized as the most active one, with 30 to 55 % of reported cases (Anonymous). The distribution of VL is given in figure 8. Highest number of cases was reported in 1922 (n = 130), 1993 and 2006 (n = 122), and 2005 (n = 120). It is worth mentioning that VL has nearly disappeared between 1974 and 1980, as a result of the anti-malaria campaign which included extensive insecticide spraying (Ben Rachid et al., 1983). The disease sporadically occurs in rural and to a lesser extent in suburban areas and mainly affects children under five years, cases in immunocompetent adults being less than 5 % (Ben Ismail & Ben Rachid, 1989; Ben Rachid et al., 1983; Besbès et al., 1994; Bouratbine et al, 1998; Hammoud et al., 2004; Pousse et al. 1995). In HIV Tunisian patients, VL is infrequent; it is best diagnosed by PCR (Kallel et al., 2007).

Fig. 8. Actual distribution of visceral leishmaniasis in Tunisia.

Materials and methods

The laboratory of parasitology of Sousse, the third major Tunisian city which is located in the central, coastal part of Tunisia, was first created in 1986. It can be considered as a central laboratory ensuring the diagnosis of parasitic diseases’ cases including leishmaniasis, sent by generalists, dermatologists, pediatricians or hematologists either from the same hospital or other hospitals mainly from governorates of central Tunisia like Kairouan, Sidi Bouzid and Mahdia. Results are usually sent back to the referring doctors so the patients can be managed as appropriate. Since its creation, the laboratory has been involved in the diagnosis of all forms of leishmaniasis.

For purposes of this retrospective study, VL and CL patients’ data, including age, sex, geographical origin and the likely place of contamination, clinical presentation and evolution without or after treatment were collected.

Diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis

The diagnosis of CL is usually achieved by the demonstration of amastigotes in Giemsa-stained smears from the fluid obtained by scraping the edges of the cutaneous lesion with a sterile lancet. In addition, the size of the identified Leishmania is carefully evaluated, because small amastigotes (< 3μ) are evocative of L. infantum and L. killicki rather than L. major whose amastigotes are larger. Over the last decade, lesions evocative of CL but found negative in direct examination were further submitted to PCR technique, known to be more sensitive.