Wai-ta-hanui

New Zealand’s oldest known tribe, said to have arrived more than 2,000 years ago. Of the original 200 tribes that dominated the islands, only 140 mixed descendants were still alive in 1988. The Waitahanui were supposed to have been prodigious mariners who navigated the world in oceangoing sailing ships, and raised colossal stone structures, of which the Kaimanawa Wall is the last surviving example. Also known as the Waitaha, or Urukehu, the “People of the West” were fair-skinned, hazel-eyed redheads, who came from a splendid kingdom overwhelmed by the sea.

Wai-Tepu

The Brazilian Indians’ forefather, who arrived long ago after his island home in the Atlantic Ocean caught fire. As he and his family sailed away to South America, their burning homeland collapsed under the sea. His name, “Mountain of the Sun,” implies volcanic Mount Atlas. Wai-Tepu’s story suggests the final destruction of Atlantis.

Wakt’cexi

In Native American oral traditions of the Upper Midwest, a horned giant who gathered up survivors of the Great Flood and carried them to safety on the eastern shores of Turtle Island (North America).

Wallanganda

A monarch who built the first cities in the Lemurian kingdom of Baralku, according to chronologer Neil Zimmerer.

Wallum Ollum

The “Red Record” is a preserved oral tradition of the Lenni Lenape, or Delaware Indians. It tells of the Talega—”strangers” or “foreigners”—who arrived on New England shores after a deluge overwhelmed their homeland across the Atlantic Ocean: “All of this was long ago, in the land beyond the great flood.Flooding and flooding, filling and filling, smashing and smashing, drowning and drowning” (topic 2, line 7).

Led by Nanabush to the North American coast, the survivors formed a new state with their “Great Sun” as monarch. He ruled over “lesser suns,” nobles, “honored men,” and the vast majority of native peasants and laborers contemptuously known as “stinkers.” The Talega eventually intermarried with these “stinkers,” and their “sun kingdom” dissolved into chaos, leaving behind impressive earthworks in abandoned ceremonial centers. Thus, the so-called “mound builders” are depicted as Atlanteans (the Talega) by the Delaware Indians.

The same story is related by a Shawnee dance ceremoniously performed in Oklahoma forest groves. The Mayas’ flood hero, as described in the cosmological epic, the Popol Vuh, arrived in Yucatan following a deluge that overwhelmed his island kingdom across the Atlantic Ocean. It was called Valum, which appears to be a Mayan contraction of Wallum Ollum—doubtless one and the same location.

Washo Deluge Story

The Washo are a native California people who recounted an early golden period of their ancestors. For many generations, they lived in happiness on a far away island, at the center of which was a tall, stone temple containing a representation of the sea-god. His likeness was so huge, its head touched the top of “the dome.” This part of the Washo account is found, perhaps surprisingly, in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, and virtually reproduces Plato’s description in Kritias of the Temple of Poseidon at the center of Atlantis, where a colossus of the sea-god was “so tall his head touched the roof.” It seems no less remarkable that the Washo,whose material culture never exceeded the construction of a tepee, would have even known about an architectural feature as sophisticated as a dome.

Their deluge story tells that violent earthquakes caused the mountains of their ancestral island to catch fire. The flames rose so high they melted the stars, which fell to Earth, spreading the conflagration around the world. Some fell into the sea, and caused a universal flood that extinguished the flames, but threatened humanity with extinction. The Washo ancestors tried to escape the rising tide by climbing to the top of the sea-god’s temple, but were changed into stones. This transformation is reminiscent of the Greek Deluge, in which Deucalion and his wife, Pyrrha, threw stones over their shoulders; as the stones struck the ground, they turned into men and women—an inverse of the Washo version.

Wegener, Alfred L.

Austrian founder of the continental drift hypothesis, which transformed established notions of geology more than any other theory in modern times. While Wegener was advocating his ideas in the early 20th century, he was no less ridiculed by his scientific contemporaries for insisting that Plato’s Atlantis was a victim of the same violent earth changes associated with plate tectonics.

Wekwek

In the North American Tuleyone Indian deluge account, Wekwek, in the guise of a falcon, was sent by a sorcerer to steal fire from heaven. But the gods pursued Wekwek, who, in his fright, dropped a burning star to Earth, where it sparked a worldwide conflagration. The Coyote-god, Olle, extinguished the flames with a universal flood.

The celestial catastrophe associated with the destruction of Atlantis appears in this Tuleyone account.

Westernesse

One of three versions of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Atlantis. (See Numinor)

Wesucechak

Alaska’s Cree Indians of the Subarctic Circle preserve traditions about a catastrophic flood that destroyed most of the world long ago. Wesucechak was a shape-shifting shaman who escaped the flood he caused when he got into a fight with the water-monsters who murdered his brother, Misapos.

Widapokwi

The Yavapai Indians of the American Southwest preserve a folk memory of Lemurian origins in their most important mythic figure, the Creatrix, or “Female Maker.” Long ago, all humanity dwelt in an underworld, from which the colossal Tree of Life grew to pierce the sky. But when the time came for men and women to emerge into the outer world, they neglected to close the hole through which they passed after them. The ocean gushed out, flooding the whole world to drown most of mankind. Widapokwi survived by riding out the cataclysm in a “hollow log,” in which she had provisioned herself with a great number of animals. After the waters subsided, she used these creatures to repopulate the Earth.Mu was synonymous for the Tree of Life.

Wigan

As told by the Ifugao, a Philippine people residing high in the cordillera of Luzon, Wigan and his sister, Bugan, were lone survivors of the Great Flood. The Ifugao version is similar to Babylonian and other accounts which describe an unusual period of extreme drought immediately prior to the deluge, accompanied by a sudden darkness, the result of volcanic eruptions and/or meteorite collisions.

Wigan and Bugan, as in accounts of flood heroes everywhere, floated safely to the top of the world’s tallest mountain. But here its name suggests the destruction of Mu: Amuyao.

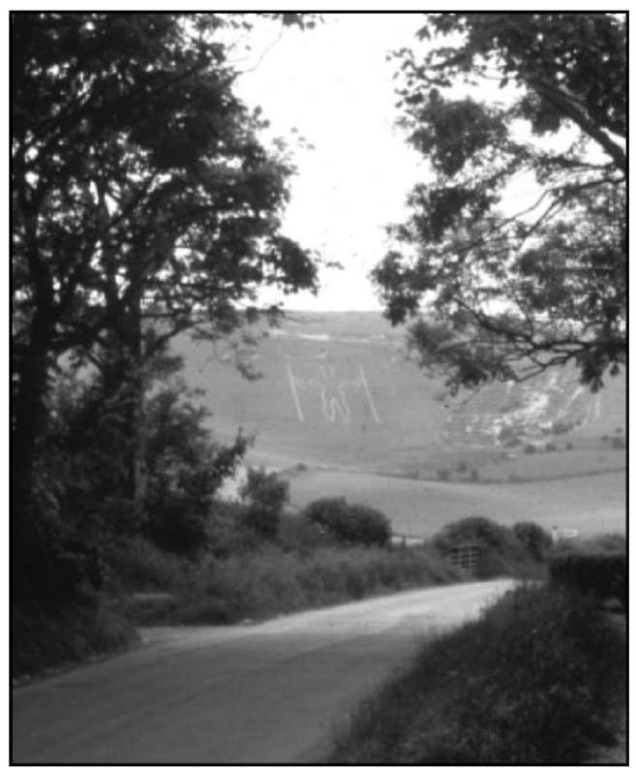

Wilmington’s Long Man, in the south of England, has Atlantean counterparts in North and South America.