The human population has maintained relatively gradual growth throughout most of history by high, and nearly equal, rates of deaths and births. Since about 1800, however, this situation has changed dramatically, as most societies have undergone major declines in mortality, setting off high growth rates due to the imbalance between deaths and births. Some societies have eventually had fertility declines and emerged with a very gradual rate of growth as low levels of births matched low levels of mortality.

There are many versions of demographic transition theory (Mason 1997), but there is some consensus that each society has the potential to proceed sequentially through four general stages of variation in death and birth rates and population growth. Most societies in the world have passed through the first two stages, at different dates and speeds, and the contemporary world is primarily characterized by societies in the last two stages, although a few are still in the second stage.

Stage 1, presumably characterizing most of human history, involves high and relatively equal birth and death rates and little resulting population growth.

Stage 2 is characterized by a declining death rate, especially concentrated in the years of infancy and childhood. The fertility rate remains high, leading to at least moderate population growth.

Stage 3 involves further declines in mortality, usually to low levels, and initial sustained declines in fertility. Population growth may become quite high, as levels of fertility and mortality increasingly diverge.

Stage 4 is characterized by the achievement of low mortality and the rapid emergence of low fertility levels, usually near those of mortality. Population growth again becomes quite low or negligible.

While demographers argue about the details of demographic change in the past 200 years, clearcut declines in birth and death rates appeared on the European continent and in areas of overseas European settlement in the nineteenth century, especially in the last three decades. By 1900, life expectancies in ”developed” societies such as the United States were probably in the mid-forties, having increased by a few years in the century (Preston and Haines 1991). By the end of the twentieth century, even more dramatic gains in mortality were evident, with life expectancies reaching into the mid- and high-seventies.

The European fertility transition of the late 1800s to the twentieth century involved a relatively continuous movement from average fertility levels of five or six children per couple to bare levels of replacement by the end of the 1930s. Fertility levels rose again after World War II, but then began another decline about 1960. Some countries now have levels of fertility that are well below long-term replacement levels.

With a few exceptions such as Japan, most other parts of the developing world did not experience striking declines in mortality and fertility until the midpoint of the twentieth century. Gains in life expectancy became quite common and very rapid in the post-World War II period throughout the developing world (often taking less than twenty years), although the amount of change was quite variable. Suddenly in the 1960s, fertility transitions emerged in a small number of societies, especially in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia, to be followed in the last part of the twentieth century by many other countries.

Clear variations in mortality characterize many parts of the world at the end of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, life expectancies in countries throughout the world are generally greater than those found in the most developed societies in 1900. A much greater range in fertility than mortality characterizes much of the world, but fertility declines seem to be spreading, including in ”laggard” regions such as sub-Saharan Africa.

The speed with which the mortality transition was achieved among contemporary lesser-developed countries has had a profound effect on the magnitude of the population growth that has occurred during the past few decades. Sweden, a model example of the nineteenth century European demographic transition, peaked at an annual rate of natural increase of 1.2 percent. In contrast, many developing countries have attained growth rates of over 3.0 percent. The world population grew at a rate of about 2 percent in the early 1970s but has now declined to about 1.4 percent, as fertility rates have become equal to the generally low mortality rates.

CAUSES OF MORTALITY TRANSITIONS

The European mortality transition was gradual, associated with modernization and raised standards of living. While some dispute exists among demographers, historians, and others concerning the relative contribution of various causes (McKeown 1976; Razzell 1974), the key factors probably included increased agricultural productivity and improvements in transportation infrastructure which enabled more efficient food distribution and, therefore, greater nutrition to ward off disease. The European mortality transition was also probably influenced by improvements in medical knowledge, especially in the twentieth century, and by improvements in sanitation and personal hygiene. Infectious and environmental diseases especially have declined in importance relative to cancers and cardiovascular problems. Children and infants, most susceptible to infectious and environmental diseases, have showed the greatest gains in life expectancy.

The more recent and rapid mortality transitions in the rest of the world have mirrored the European change with a movement from infectious/environmental causes to cancers and cardiovascular problems. In addition, the greatest beneficiaries have been children and infants. These transitions result from many of the same factors as the European case, generally associated with economic development, but as Preston (1975) outlines, they have also been influenced by recent advances in medical technology and public health measures that have been imported from the highly-developed societies. For instance, relatively inexpensive vaccines are now available throughout the world for immunization against many infectious diseases. In addition, airborne sprays have been distributed at low cost to combat widespread diseases such as malaria. Even relatively weak national governments have instituted major improvements in health conditions, although often only with the help of international agencies.

Nevertheless, mortality levels are still higher than those in many rich societies due to such factors as inadequate diets and living conditions, and inadequate development of health facilities such as hospitals and clinics. Preston (1976) observes that among non-Western lesser-developed countries, mortality from diarrheal diseases (e.g., cholera) has persisted despite control over other forms of infectious disease due to the close relationship between diarrheal diseases, poverty, and ignorance—and therefore a nation’s level of socioeconomic development.

Scholars (Caldwell 1986; Palloni 1981) have warned that prospects for future success against high mortality may be tightly tied to aspects of social organization that are independent of simple measures of economic well-being: Governments may be more or less responsive to popular need for improved health; school system development may be important for educating citizens on how to care for themselves and their families; the equitable treatment of women may enhance life expectancy for the total population.

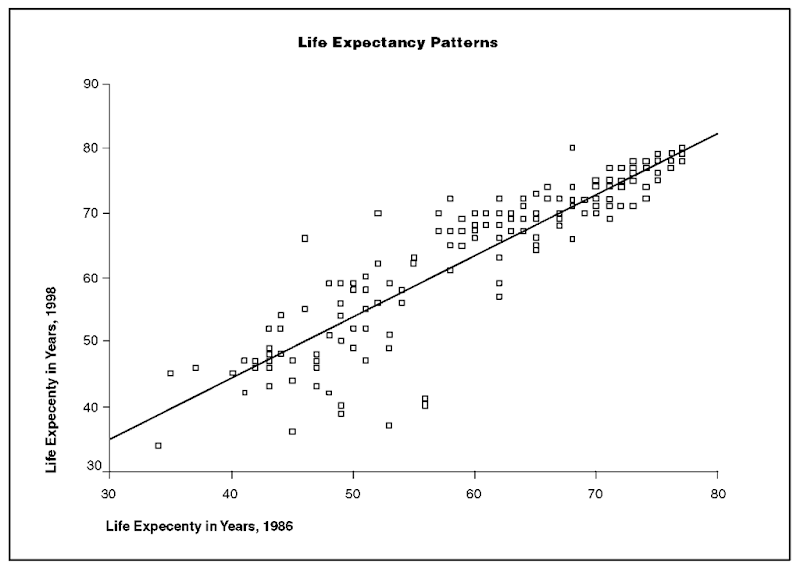

Recent worldwide mortality trends may be charted with the help of data on life expectancy at age zero that have been gathered, sometimes on the basis of estimates, by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), a highly respected chronicler of world vital rates. For 165 countries with relatively stable borders over time, it is possible to relate estimated life expectancy in 1986 with the same figure for 1998. Of these countries, only 13.3 percent showed a decline in life expectancy during the time period. Some 80.0 percent had overall increasing life expectancy, but the gains were highly variable. Of all the countries, 29.7 percent actually had gains of at least five years or more, a sizable change given historical patterns of mortality.

An indication of the nature of change may be discerned by looking at Figure 1, which shows a graph of the life expectancy values for the 165 countries with stable borders. Each point represents a country and shows the level of life expectancy in 1986 and in 1998. Note the relatively high levels of life expectancy by historical standards for most countries in both years. Not surprisingly, there is a strong tendency for life expectancy values to be correlated over time. A regression straight line, indicating average life expectancy in 1998 as a function of life expectancy in 1986 describes this relationship. As suggested above, the levels of life expectancy in 1998 tend to be slightly higher than the life expectancy in 1986. Since geography is highly associated with economic development, the points on the graph generally form a continuum from low to high life expectancy. African countries tend to have the lowest life expectancies, followed by Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. Europe has the highest life expectancies.

The African countries comprise virtually all the countries with declining life expectancies, probably a consequence of their struggles with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), malnutrition, and civil disorder. Many of them have lost several years of life expectancy in a very short period of time. However, a number of the African countries also have sizeable increases in life expectancies.

Asian and American countries dominate the mid-levels of life expectancy, with the Asian countries showing a strong tendency to increase their life expectancies, consistent with high rates of economic development.

Unfortunately, Figure 1 does not include the republics of the former Soviet Union, since exactly comparable data are not available for both time points. Nevertheless, there is some consensus among experts that life expectancy has deteriorated in countries such as Russia that have made the transition from communism to economically-unstable capitalism.

WHAT DRIVES FERTILITY RATES?

The analysis of fertility decline is somewhat more complicated analytically than mortality decline. One may presume that societies will try, if given resources and a choice, to minimize mortality levels, but it seems less necessarily so that societies have an inherent orientation toward low fertility, or, for that matter, any specific fertility level. In addition, fertility rates may vary quite widely across societies due to factors (Bongaarts 1975) that have little relationship to conscious desires such as prolonged breastfeeding which supresses reproductive ovulation in women, the effectiveness of birth control methods, and the amount of involuntary foetal abortion. As a result of these analytic ambiguities, scholars seem to have less consensus on the social factors that might produce fertility than mortality decline (Hirschman 1994; Mason 1997).

Figure 1

Coale (1973), in an attempt to reconcile the diversity of circumstances under which fertility declines have been observed to occur, identified three major conditions for a major fall in fertility:

1. Fertility must be within the calculus of conscious choice. Parents must consider it an acceptable mode of thought and form of behavior to balance the advantages and disadvantages of having another child.

2. Reduced fertility must be viewed as socially or economically advantageous to couples.

3. Effective techniques of birth control must be available. Sexual partners must know these techniques and have a sustained will to use the them.

Beyond Coale’s conditions, little consensus has emerged on the causes of fertility decline. There are, however, a number of major ideas about what causes fertility transitions that may be summarized in a few major hypotheses.

A major factor in causing fertility change may be the mortality transition itself. High-mortality societies depend on high fertility to ensure their survival. In such circumstances, individual couples will maximize their fertility to guarantee that at least a few of their children survive to adulthood, to perpetuate the family lineage and to care for them in old age. The decline in mortality may also have other consequences for fertility rates. As mortality declines, couples may perceive that they can control the survival of family members by changing health and living practices such as cleanliness and diet. This sense of control may extend itself to the realm of fertility decisions, so that couples decide to calculate consciously the number of children they would prefer and then take steps to achieve that goal.

Another major factor may be the costs and benefits of children. High-mortality societies are often characterized by low technology in producing goods; in such a situation (as exemplified by many agricultural and mining societies), children may be economically useful to perform low-skilled work tasks. Parents have an incentive to bear children, or, at the minimum, they have little incentive not to bear children. However, high-technology societies place a greater premium on highly-skilled labor and often require extended periods of education. Children will have few economic benefits and may become quite costly as they are educated and fed for long periods of time.

Another major factor that may foster fertility decline is the transfer of functions from the family unit to the state. In low-technology societies, the family or kin group is often the fundamental unit, providing support for its members in times of economic distress and unemployment and for older members who can no longer contribute to the group through work activities. Children may be viewed as potential contributors to the unit, either in their youth or adulthood. In high-technology societies, some of the family functions are transferred to the state through unemployment insurance, welfare programs, and old age retirement systems. The family functions much more as a social or emotional unit where the economic benefits of membership are less tangible, thus decreasing the incentive to bear children.

Other major factors (Hirschman 1994; Mason 1997) in fertility declines may include urbanization and gender roles. Housing space is usually costly in cities, and the large family becomes untenable. In many high-technology societies, women develop alternatives to childbearing through employment outside their homes, and increasingly assert their social and political rights to participate equally with men in the larger society. Because of socialization, men are generally unwilling to assume substantial child-raising responsibilities, leaving partners with little incentive to participate in sustained childbearing through their young adult lives.

No consensus exists on how to order these theories in relative importance. Indeed, each theory may have more explanatory power in some circumstances than others, and their relative importance may vary over time. For instance, declines in mortality may be crucial in starting fertility transitions, but significant alterations in the roles of children may be key for completing them. Even though it is difficult to pick the ”best” theory, every country that has had a sustained mortality decline of at least thirty years has also had some evidence of a fertility decline. Many countries seem to have the fertility decline precondition of high life expectancy, but fewer have achieved the possible preconditions of high proportions of the population achieving a secondary education.

EUROPEAN FERTILITY TRANSITION

Much of what is known about the process of fertility transition is based upon research at Princeton University (known as the European Fertility Project) on the European fertility transition that took place primarily during the seventy-year period between 1870 and 1940. Researchers used aggregate government-collected data for the numerous ”provinces” or districts of countries, typically comparing birth rates across time and provinces.

In that almost all births in nineteenth-century Europe occurred within marriage, the European model of fertility transition was defined to take place at the point marital fertility was observed to fall by more than 10 percent (Coale and Treadway 1986). Just as important, the Project scholars identified the existence of varying levels of natural fertility (birth rates when no deliberate fertility control is practiced) across Europe and throughout European history (Knodel 1977). Comparative use of natural fertility models and measures derived from these models have been of enormous use to demographers in identifying the initiation and progress of fertility transitions in more contemporary contexts.

Most scholars have concluded that European countries seemed to start fertility transitions from very different levels of natural fertility but moved at quite similar speeds to similar levels of controlled fertility on the eve of World War II (Coale and Treadway 1986). As the transition progressed, areal differences in fertility within and across countries declined, while the remaining differences were heavily between countries (Watkins 1991).

Although some consensus has emerged on descriptive aspects of the fertility transition, much less agreement exists on the social and economic factors that caused the long-term declines. Early theorists of fertility transitions (Notestein 1953) had posited a simple model driven by urban-industrial social structure, but this perspective clearly proved inadequate. For instance, the earliest declines did not occur in England, the most urban-industrial country of the time, but were in France, which maintained a strong rural culture. The similarity of the decline across provinces and countries of quite different social structures also seemed puzzling within the context of previous theorizing. Certainly, no one has demonstrated that variations in the fertility decline across countries, either in the timing or the speed, were related clearly to variations in crude levels of infant mortality, literacy rates, urbanization, and industrialization. Other findings from recent analysis of the European experience include the observation that in some instances, reductions in fertility preceded reductions in mortality (Cleland and Wilson 1987), a finding that is inconsistent with the four-stage theory of demographic transition.

The findings of the European Fertility Project have led some demographers (Knodel and van de Walle 1979) to reformulate ideas about why fertility declined. They suggest that European couples were interested in a small family well before the actual transition occurred. The transition itself was especially facilitated by the development of effective and cheap birth control devices such as the condom and diaphragm. Information about birth control rapidly and widely diffused through European society, producing transitions that seemed to occur independently of social structural factors such as mortality, urbanization, and educational attainment. In addition, these scholars argue that ”cultural” factors were also important in the decline. This is based on the finding that provinces of some countries such as Belgium differed in their fertility declines on the basis of areal religious composition (Lesthaeghe 1977) and that, in other countries such as Italy, areal variations in the nature of fertility decline were related to political factors such as the Socialist vote, probably reflecting anticlericalism (Livi-Bacci 1977). Others (Lesthaeghe 1983) have also argued for ”cultural” causes of fertility transitions.

While the social causes of the European fertility transition may be more complex than originally thought, it may still be possible to rescue some of the traditional ideas. For instance, mortality data in Europe at the time of the fertility transition were often quite incomplete or unreliable, and most of the studies focused on infant (first year of life) mortality as possible causes of fertility decline. Matthiessen and McCann (1978) show that mortality data problems make some of the conclusions suspect and that infant mortality may sometimes be a weak indicator of child survivorship to adulthood. They argue that European countries with the earliest fertility declines may have been characterized by more impressive declines in post-infant (but childhood) mortality than infant mortality.

Conclusions about the effects of children’s roles on fertility decline have often been based on rates of simple literacy as an indicator of educational system development. However, basic literacy was achieved in many European societies well before the major fertility transitions, and the major costs of children would occur when secondary education was implemented on a large scale basis, which did not happen until near the end of the nineteenth century (Van de Walle 1980). In a time-series analysis of the United States fertility decline from 1870 to the early 1900s, Guest and Tolnay (1983) find a nearly perfect tendency for the fertility rate to fall as the educational system expanded in terms of student enrollments and length of the school year. Related research also shows that educational system development often occurred somewhat independently of urbanization and industrialization in parts of the United States (Guest 1981).

An important methodological issue in the study of the European transition (as in other transitions) is how one models the relationship between social structure and fertility. Many of the research reports from the European Fertility Project seem to assume that social structure and fertility had to be closely related at all time points to support various theories about the causal importance of such factors as mortality and children’s roles, but certain lags and superficial inconsistencies do not seem to prove fundamentally that fertility failed to respond as some of the above theories would suggest. The more basic question may be whether fertility eventually responded to changes in social structure such as mortality.

Even after admitting some problems with previous traditional interpretations of the European fertility transition, one cannot ignore the fact that the great decline in fertility occurred at almost the same time as the great decline in mortality and was associated (even if loosely) with a massive process of urbanization, industrialization, and the expansion of educational systems.

FERTILITY TRANSITIONS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

The great majority of countries in the developing world have undergone some fertility declines in the second half of the twentieth century. While the spectacularly rapid declines (Taiwan, South Korea) receive the most attention, a number are also very gradual (e.g. Guatemala, Haiti, Iraq, Cambodia), and a number are so incipient (especially in Africa) that their nature is difficult to discern.

The late twentieth century round of fertility transitions has occurred in a very different social context than the historical European pattern. In the past few decades, mortality has declined very rapidly. National governments have become very attuned to checking their unprecedented national growth rates through fertility control. Birth control technology has changed greatly through the development of inexpensive methods such as the intrauterine device (IUD). The world has become more economically and socially integrated through the expansion of transportation and developments in electronic communications, and ”Western” products and cultural ideas have rapidly diffused throughout the world. Clearly, societies are not autonomous units that respond demographically as isolated social structures.

Leaders among developing countries in the process of demographic transition were found in East Asia and Latin America, and the Carribbean (Coale 1983). The clear leaders among Asian nations, such as South Korea and Taiwan, generally had experienced substantial economic growth, rapid mortality decline, rising educational levels, and exposure to Western cultural influences (Freed-man 1998). By 1998, South Korea and Taiwan had fertility rates that were below long-term replacement levels. China also experienced rapidly declining fertility, which cannot be said to have causes in either Westernization or more than moderate economic development, with a life expectancy estimated at seventy-one years and a rate of natural increase of 1.0 percent (PRB 1998).

Major Latin American nations that achieved substantial drops in fertility (exceeding 20 percent) in recent decades with life expectancies surpassing sixty years include Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Mexico, and Venezuela. All of these have also experienced substantial changes in mortality, education, or both, and economic development.

Unlike the European historical experience, fertility declines in the post-1960 period have not always sustained themselves until they reached near replacement levels. A number of countries have started declines but then leveled off with three or four children per reproductive age woman. For instance, Malaysia was considered a ”miracle” case of fertility decline, along with South Korea and Taiwan, but in recent years its fertility level has stabilized somewhat above the replacement level.

Using the PRB data for 1986 and 1998, we can trace recent changes for 166 countries in estimated fertility as measured by the Total Fertility Rate (TFR), an indicator of the number of children typically born to a woman during her lifetime. Some 80.1 percent of the countries showed declines in fertility. Of all the countries, 37.3 percent had a decline of at least one child per woman, and 9.0 percent had a decline of at least two children per woman.

The region that encompasses countries having the highest rates of population growth is sub-Saharan Africa. Growth rates generally exceed 2 percent, with several countries having rates that clearly exceed 3 percent. This part of the world has been one of the latest to initiate fertility declines, but in the 1986-1998 period, Botswana, Kenya, and Zimbabwe all sustained fertility declines of at least two children per woman, and some neighboring societies were also engaged in fertility transition. At the same time, many sub-Saharan countries are pre-transitional or only in the very early stages of a transition. Of the twenty-five countries that showed fertility increases in the PRB data, thirteen of them were sub-Saharan nations with TFRs of at least 5.0.

In general, countries of the Middle East and regions of Northern Africa populated by Moslems have also been slow to embark on the process of fertility transition. Some (Caldwell 1976) found this surprising since a number had experienced substantial economic advances and invited the benefits of Western medical technology in terms of mortality reduction. Their resistance to fertility transitions had been attributed partly to an alleged Moslem emphasis on the subordinate role of women to men, leading them to have limited alternatives to a homemaker role. However, the PRB data for 1986-1998 indicate that some of these countries (Algeria, Bangladesh,Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Syria, Turkey) are among the small number that achieved reduction of at least two children per woman.

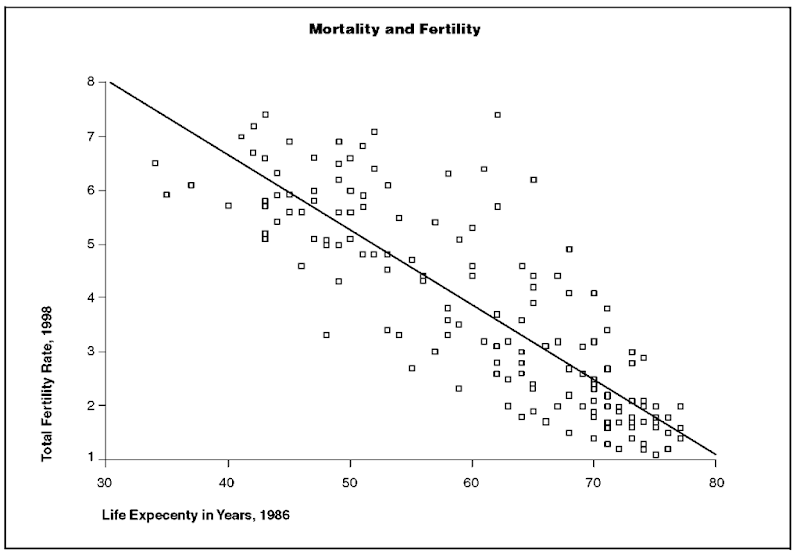

The importance of the mortality transition in influencing the fertility transition is suggested by Figure 2. Each dot is a country, positioned in terms of graphical relationship in the PRB data between life expectancy in 1986 and the TFR in 1998. The relationship is quite striking. No country with a life expectancy less than fifty has a TFR below 3.0. Remember that before the twentieth century, virtually all countries had life expectancies below fifty years. In addition, the figure shows a very strong tendency for countries with life expectancies above seventy to have TFRs below 2.0.

For a number of years, experts on population policy were divided on the potential role of contraceptive programs in facilitating fertility declines (Davis 1967). Since contraceptive technology has become increasingly cheap and effective, some (Enke 1967) argue that modest international expenditures on these programs in high-fertility countries could have significant rapid impacts on reproduction rates. Others (Davis 1967) point out, however, that family planning programs would only permit couples to achieve their desires, which may not be compatible with societal replacement level fertility. The primary implication was that family planning programs would not be effective without social structures that encouraged the small family. A recent consensus on the value of family planning programs relative to social structural change seems to have emerged. Namely, family planning programs may be quite useful for achieving low fertility where the social structure is consistent with a small family ideal (Mauldin and Berelson 1978).

While the outlook for further fertility declines in the world is good, it is difficult to say whether and when replacement-level fertility will be achieved. Many, many major social changes have occurred in societies throughout the world in the past half-century. These changes have generally been unprecented in world history, and thus we have little historical experience from which to judge their impact on fertility, both levels and speed of change (Mason 1997).

Some caution should be excercised about future fertility declines in some of the societies that have been viewed as leaders in the developing world. For instance, in a number of Asian societies, a strong preference toward sons still exists, and couples are concerned as much about having an adequate number of sons survive to adulthood as they are about total sons and daughters. Since pre-birth gender control is still difficult, many couples have a number of girl babies before they are successful in bearing a son. If effective gender control is achieved, some of these societies will almost certainly attain replacement-level fertility.

In other parts of the world such as sub-Saharan Africa, the future of still-fragile fertility transitions may well depend on unknown changes in the organization of families. Caldwell (1976), in a widely respected theory of demographic transition that incorporates elements of both cultural innovation and recognition of the role of children in traditional societies in maintaining net flows of wealth to parents, has speculated that the traditional extended kinship family model now predominant in the region facilitates high fertility. Families often form economic units where children are important work resources. The extended structure of the household makes the cost of any additional member low relative to a nuclear family structure. Further declines in fertility will depend on the degree to which populations adopt the ”Western” nuclear family, either through cultural diffusion or through autonomous changes in local social structure.

Figure 2

Taking the long view, the outlook for a completed state of demographic transition for the world population as a whole generally appears positive if not inevitable, although demographers are deeply divided on estimates of the size of world population at equilibrium, the timing of completed transition, the principal mechanisms at work, and the long-term ecological consequences. Certainly, the world population will continue to grow for some period of time, if only as a consequence of the previous momentum of high fertility relative to mortality. Most if not all demographers, however, subscribe to the view expressed by Coale (1974, p. 51) that the entire process of global demographic transition and the phase of phenomenal population growth that has accompanied it will be a transitory (albeit spectacular) episode in human population history.