Parenting or child rearing styles are parents’ characteristic, consistent manner of interacting with their children across a wide range of everyday situations. Research on parenting styles has demonstrated their influence on children’s developmental outcomes, including academic skills and achievement, aggression, altruism, delinquency, emotion regulation and understanding, moral internalization, motivation, peer relations, self-esteem, social skills and adjustment, substance abuse, and mental health.

CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

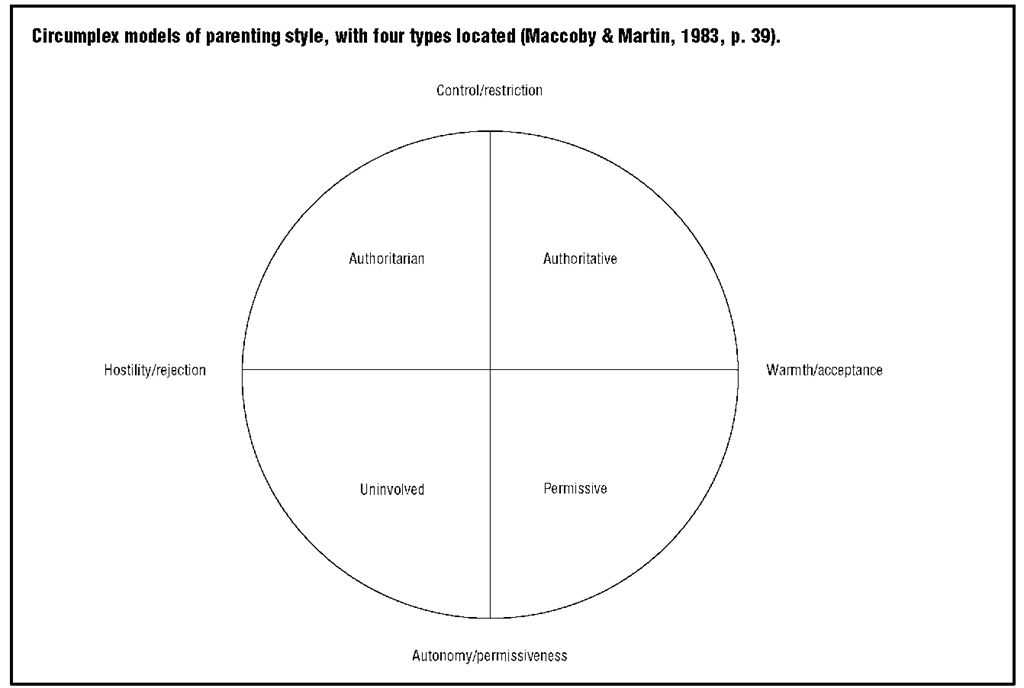

Researchers have developed three primary ways of classifying parenting styles. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Earl Schaefer and Wesley Becker proposed circumplex models of parenting. Their models have in common two independent dimensions proposed as important in understanding parenting style (see Figure 1). One dimension involves parents’ emotional or affectionate attitude toward the child; the other, parents’ exertion of control over the child’s behavior. Because each dimension forms a continuous measure, parents’ individual styles may be mapped anywhere within the circumplex.

The system developed by Jeanne Humphries Block in the mid-1960s is multifaceted. Block noted that the structure of parenting or childrearing styles may vary across groups of parents; thus, defining a universal set of parenting dimensions may be neither desirable nor possible. Nonetheless, like Schaefer and Becker, Block’s work has identified dimensions related to parental control or restriction of children’s behavior, and to parents’ emotional attitude or responsiveness to the child. Additionally, Block noted that the degree to which parents find child-rearing to be satisfying and are involved with their child, among other dimensions, may be important in understanding parenting styles and their influence on children’s outcomes. In the late 1980s, William Roberts and Janet Strayer conducted further work with Block’s measurement system that suggested five dimensions: (1) parents’ warmth and closeness rather than coolness and distance; (2) parental strictness and use of punishment; (3) parental encouragement of children’s boldness and maturity; (4) parents’ enjoyment of and involvement in parenting; and (5) parents’ encouragement or discouragement of children’s emotional expressions. Composition of these dimensions differed somewhat between mothers and fathers.

In the late 1960s, Diana Baumrind formulated a typology including three distinct parenting styles: authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive. These parenting styles vary according to parents’ demand that their children meet standards for behavior and their responsiveness to their children’s needs. Authoritative parents are high in both demand and responsiveness. They communicate to their children about expectations and standards in a warm and responsive manner. Authoritarian parents are highly demanding but are neither warm nor responsive to their children’s behavior. Their expectations and demands are communicated with little to no rationale or warmth. Permissive parents are moderate in responsiveness and warmth and low in demand, tending to accept children’s impulses. There is an absence of parental enforcement of expectations or standards for children’s behaviors.

Figure 1

In 1983 Eleanor Maccoby and John Martin integrated extant theory and research and proposed four parenting styles, differing along the two dimensions of control or demand and warmth or responsiveness that are held in common in all three preceding systems and incorporating parental involvement into those dimensions. Maccoby and Martin’s reconceptualization proposes three styles similar to Baumrind’s typology, and in addition a fourth style, uninvolved or neglectful parenting, which is characterized by both a low degree of parental demand that the child meet behavioral expectations and by low warmth and responsiveness to children’s needs (see Figure 1). These parents may appear distant and uninterested in their children, or may respond to children in a manner designed only to end children’s requests rather than to help their child develop. These four parenting styles are generally used.

ASSESSMENT METHODS

Parent and child self-report and naturalistic observations have been used to assess parenting style. Q sort tasks, in which parents or outside observers (i.e., researchers, teachers) divide a set of statements into piles according to how characteristic they are of the parents’ typical style, have been popular in measuring parenting or childrearing style because they may reduce some self-report or observer bias. One area of controversy in measurement is whether parents should be assigned to mutually exclusive categories (typological approach) or whether parents’ extent of using each parenting style or dimension (dimensional approach) should be measured. For example, using the typological approach, a parent would be described as authoritative if most of his or her parenting behaviors fit that style, even if he or she showed frequent authoritarian and occasional permissive behaviors. Using the dimensional approach, the same parent would receive scores for each parenting style, high for authoritative, moderate for authoritarian, and low for permissive, reflecting the extent to which they were used. In 1994 Laurence Steinberg and colleagues described the typological approach as most appropriate for assessing short-term child outcomes because parents’ predominant style is emphasized. Conversely, because the dimensional approach includes measurement of all parenting styles, in their 1989 work Wendy Grolnick and Richard Ryan noted the advantage of investigating independent and joint effects of parenting styles on children’s outcomes.

RELATIONS TO CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOMES

Parenting styles are often used in investigating diverse developmental outcomes, such as academic competence, achievement, self-esteem, aggression, delinquency and substance abuse, moral reasoning, and social adjustment. Research suggests that authoritative parenting is conducive to optimal development. Specifically, children reared by authoritative parents demonstrate higher competence, achievement, social development, and mental health compared to those reared by authoritarian or permissive parents. Negative effects of authoritarian parenting on children’s outcomes include poorer self-esteem, social withdrawal, and low levels of conscience. Permissive parenting has been related to negative outcomes such as behavioral misconduct and substance abuse. The worst outcomes for children are associated with neglectful parenting. This lack of parenting is associated with delinquency, negative psy-chosocial development, and lower academic achievement. Longitudinal research by Steinberg and colleagues supports these concurrent associations such that children raised by authoritative parents continued to display positive developmental outcomes one year following measurement of parenting style, whereas those raised by neglectful or indifferent parents had further augmented negative outcomes.

From Baumrind’s framework, in authoritative homes children’s adaptive skills are developed through the open communication characteristic of parent-child interactions. Parents’ clear expectations for children’s behavior and responsiveness to children’s needs provide an environment that supports children’s development of academic and social competence. Authoritative parenting does seem to be robustly associated with positive outcomes across ethnically and socioeconomically diverse populations, though the strength of the association varies.

Less clear is whether permissive and authoritarian parenting styles have negative effects on children’s development in varying contexts. In 1981 Catherine Lewis questioned whether the positive outcomes associated with authoritative parenting were due to the combination of demand and responsiveness, or rather to the warm and caring parent-child relationship. When a parent-child relationship has few conflicts, and therefore there is little need for parents to exert control over children’s behavior, permissive parenting might be as effective as authoritative parenting. Indeed, from an attribution theory framework, parents’ absence of controlling children’s behavior would be expected to lead to children’s internalization of behaviors and values. Research in the United States and in China in the 1990s and 2000s suggested that the combination of greater parental warmth or support and less parental control or punishment is related concurrently or retrospectively to positive outcomes such as self-esteem, prosocial behavior, socioemotional skills, and family harmony.

Lewis proposed that the firm but not punitive control characteristic of authoritative parenting might be more reflective of children’s willingness to obey than of parents’ style. In 1994 Joan Grusec developed a theoretical model that elaborated children’s role in accurately perceiving and choosing to accept or reject their parents’ communication of behavioral standards through disciplinary practices and parenting style. Few researchers have investigated such bidirectional child effects on parenting styles. An exception is Janet Strayer and William Roberts’s 2004 research, in which they statistically tested whether children’s anger elicited parents’ control and lack of warmth and found greater evidence for parenting style leading to children’s anger and thereby impacting children’s empathy.

Some research indicates a lack of negative or even positive outcomes for children whose parents are highly strict and authoritarian, depending on the family’s ethnicity (e.g., African American, Clark et al. 2002; Palestinian-Arab, Dwairy 2004). In 2004 Enrique Varela and colleagues found that it was not ethnicity per se (nor assimilation, socioeconomic status, or parental education), but rather ethnic minority status that was related to greater endorsement of authoritarian parenting by Mexican immigrant and Mexican American families living in the United States compared to both white, non-Hispanic families living in the United States and Mexican families living in Mexico. Varela and colleagues have called for research to examine ecological influences on parenting style and on the effects of parenting style on children’s outcomes.

Finally, reminiscent of Block’s perspective, some research suggests that additional or redefined parenting styles and dimensions may be necessary to understand parenting cross-culturally. Filial piety and individual humility, which involve emphasizing family or group obligations, achievements, and interests over individual goals and expressions, are two parenting values that have been identified in Hong Kong and mainland Chinese families. Peixia Wu and colleagues (2002) cautioned that, despite seeming similarities between Chinese parenting dimensions such as directiveness and maternal involvement and the demand and responsiveness characteristic of authoritative parenting, the meaning of the dimensions and their relations to one another seem to vary considerably between Chinese and American mothers. Thus, although parenting style may provide a useful framework for understanding developmental outcomes, it is critical to consider the meaning of parenting practices and styles within the family’s cultural context.