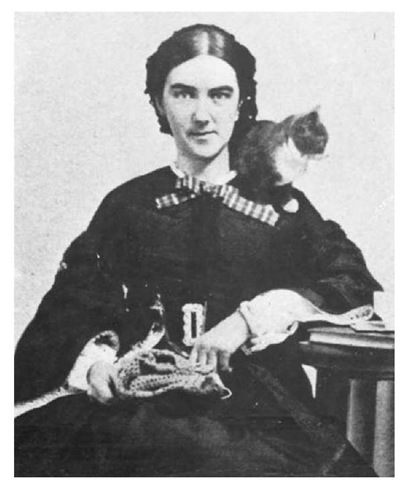

Ellen Swallow Richards is considered the mother of euthenics, or the study of environmental improvement as a means of human improvement, as well as of ecology and home economics. She taught housewives practical ways to use science to improve their families’ health. She was also the first woman to graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where she remained for the rest of her career, and the first woman in the United States to earn a bachelor of science degree in chemistry.

Ellen Henrietta Swallow was born on December 3, 1842, in Dunstable, Massachusetts. Her mother, Fanny Gould Taylor, was a teacher, as was her father, Peter Swallow. She helped her parents tend their farm and keep their grocery store, and in return they educated their only daughter at home, until her intellectual appetite outstripped their ability to feed it. At that point, the family moved to the nearby town, home to Westford Academy, which she attended. After graduating in 1863, she taught in Littleton, Massachusetts, where she worked various other jobs (nursing, tutoring, storekeeping, cooking, and housecleaning) to save money for furthering her education.

In September 1868, at the age of 26, Swallow enrolled at Vassar, a women’s college, where she studied astronomy under Maria Mitchell and applied chemistry under Charles Farrar. She completed its four-year curriculum in two years to become a member of Vassar’s first graduating class, earning her bachelor of arts degree in 1870. Seeking further education in chemistry, she became the first woman to enroll at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in January 1871. MIT dubbed her studies as the "Swallow experiment," considering her a kind of guinea pig testing the educability of women. In 1873, she submitted a thesis entitled "Notes on Some Sulpharsenites and Sulphantimonites from Colorado" to become the first woman in the United States to earn a bachelor of science degree in chemistry.

That same year, Swallow isolated a new metal, vanadium, from iron ore, and composed a thesis on this research to earn a master of arts degree from Vassar College. She was granted an Artium Omnium Magistra by MIT, which retained her as an untitled and unsalaried instructor and laboratory assistant. She continued her studies, though MIT voted at that time to disallow women from receiving doctorates. However, her achievement did convince the institute to vote, on May 11, 1876, in favor of allowing women to officially enroll at MIT. The year before, she had married Robert Hallowell Richards, the head of MIT’s department of mining engineering, on June 4, 1875.

Ellen Swallow Richards appealed to the Women’s Education Association of Boston to fund a women’s laboratory at MIT, which was established in 1876. Serving as an assistant to lab director John M. Ordway, she instructed a small group of women in chemical analysis, industrial chemistry, mineralogy, and biology. MIT closed the women’s laboratory in 1883 (allowing all its students to matriculate into the regular curriculum), but the next year, it opened a new laboratory for the study of sanitary chemistry. As the lab’s principal instructor, Richards taught air, water, and sewage analysis.

Ellen Swallow Richards is considered the mother of home economics.

In 1881, Richards collaborated with Marion Talbot to form the Association of Collegiate Alumnae (now the American Association of University Women, or AAUW). She published her first book, The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning: A Manual for House-keepers, in 1882, following up with Food Materials and Their Adulterations in 1885 and Home Sanitation in 1887. That year, she commenced a two-year survey of Massachusetts’s inland waters, analyzing some 40,000 water samples. Her study raised concern over the management of the environment, exposing more human damage than had been suspected. She fused these concerns with the more practical concerns of "home economics," or the management of the household, to found a discipline that she called ecology, though the title met with resistance (Melvill Dewey refused to include ecology in his classification system).

In Boston in 1890, Richards founded the New England Kitchen to teach women about proper food hygiene. Nine years later, she organized a conference on home economics at Lake Placid, New York; nine years after that, in 1908, she helped establish the American Home Economics Association, serving as president for its first two years. She even underwrote the publication of the association’s Journal of Home Economics. She published almost a dozen books in the 20th century, including new editions of Food Materials and Their Adulterations in 1906, and The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning in 1910, as well as Euthenics: Science of Controllable Environment in 1910.

In 1910, Richards finally became a doctor when Smith College granted her an honorary doctorate. She died of heart disease in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, the next year, on March 30, 1911.