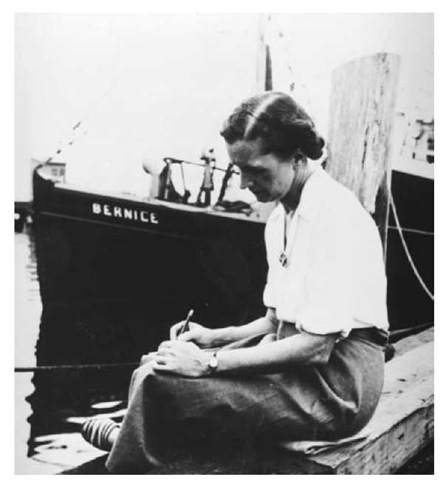

Rachel Carson combined a professional knowledge of science (she trained as a marine biologist) with poetic writing skill to create best-selling books about the sea. Her impact on history, however, resulted from a book she did not really want to write: a warning that unless human exploitation of the environment was curbed, much of nature might be destroyed. Carson’s book Silent Spring introduced the idea of ecology to the American public and almost single-handedly spawned the environmental movement.

Rachel Carson was born in Springdale, Pennsylvania, on May 27, 1907. Her father, Robert, sold insurance and real estate. Her family never had much money, but the 65 acres of land around their home near the Allegheny Mountains was rich in natural beauty, which her mother, Maria, taught her to love. "I can remember no time when I wasn’t interested in the out-of-doors and the whole world of nature," Carson once said.

When Carson entered Pennsylvania College for Women (later Chatham College) on a scholarship, she planned to become a writer. A biology class with an inspired teacher made her change her major to zoology, however. She graduated magna cum laude in 1929 and obtained another scholarship, to do graduate work at Johns Hopkins University. She also began summer work at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole. Massachusetts. Carson had always loved reading about the sea, and Woods Hole gave her a long-awaited chance not only to see the ocean but also to work in it. She obtained a master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins in 1932.

Carson taught part-time at Johns Hopkins and at the University of Maryland for several years. Then in 1935 her father died suddenly and her mother moved in with her. A year later her older sister also died, making orphans of Carson’s two young nieces, Virginia and Marjorie. Carson and her mother adopted the girls.

Needing a full-time job to support her family, Carson applied to the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. In August 1936 she was hired as a junior aquatic biologist—one of the first two women employed there for anything except clerical work. Elmer Higgins, Carson’s supervisor, recognized her writing ability and steered most of her work in that direction. He rejected one of her radio scripts, however, saying it was too literary for his purposes. He suggested that she make it into an article for Atlantic Monthly, and it appeared as "Undersea" in the magazine’s September 1937 issue.

The result,Under the Sea Wind, appeared in November 1941. Critics liked it, but the United States entered World War II a month later, and book buyers found themselves with little interest to spare for poetic descriptions of nature. The book sold poorly.

Carson continued her writing for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, created in 1940 when the Bureau of Fisheries and the Biological Survey merged. She became editor in chief of the agency’s publications division in 1947. In 1948, she began work on another book, drawing on information about oceanography that the government had obtained during the war. That book, The Sea Around Us, described the physical nature of the oceans. It was more scientific and less poetic than Carson’s first book. Published in 1951, it became an immediate best-seller, remaining on the New York Times list of top-selling books for a year and a half. It also received many awards, including the National Book Award and the John Burroughs Medal.

Suddenly Rachel Carson found herself famous and, for the first time, relatively free of money worries. In June 1952, she quit her U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service job to write full-time. A year later she built a home on the Maine coast, surrounded by "salt smell and the sound of water, and the softness of fog." She shared it with her mother; her niece, Marjorie; and Marjorie’s baby son, Roger. When Marjorie died in 1957, Carson adopted Roger and raised him.

Carson’s third book, The Edge of the Sea, described seashore life. Published in 1955, it sold almost as well as The Sea Around Us and garnered its own share of awards, including the Achievement Award of the American Association of University Women. The book that gave Rachel Carson a place in history, however, was yet to be written. It grew out of an urgent letter that a friend, Olga Owens Huckins, sent to her in 1957 after a plane sprayed clouds of the pesticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) over the bird sanctuary that Huckins and her husband owned near Duxbury, Massachusetts. Government officials told Huckins that the spray was a "harmless shower" that would kill only mosquitoes, but the morning after the plane passed over, Huckins found seven dead songbirds. "All of these birds died horribly," she wrote. "Their bills were gaping open, and their splayed claws were drawn up to their breasts in agony." Huckins asked Carson’s help in alerting the public to the dangers of pesticides.

Silent Spring appeared in 1962. It took its title from the "fable" at the book’s beginning, which pictured a spring that was silent because pesticides had destroyed singing birds and much other wildlife. The health of the human beings in her scenario was imperiled as well. This was the only fiction in the book.

Carson’s book did more than condemn pesticides. These toxic chemicals, she said, were just one example of humans’ greed, misunderstanding, and exploitation of nature. "The ‘control of nature is a phrase conceived in arrogance born of the . . . [belief] . . . that nature exists for the convenience of man." People failed to understand that all elements of nature, including human beings, are interconnected, and that damage to one meant damage to all. Carson used the word ecology, from a Greek word meaning "household," to describe this relatedness.

Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring is often cited as the inspiration for the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

The reporter Adela Rogers St. Johns wrote that Silent Spring "caused more uproar . . . than any book by a woman author since Uncle Tom’s Cabin started a great war." The powerful pesticide industry claimed that if Carson’s supposed demand to ban all pesticides—a demand she never actually made—were followed, the country would plunge into a new Dark Age because pest insects would devour its food supplies, and insect carriers such as mosquitoes would spread disease everywhere. The media portrayed Carson as an emotional female with no scientific background, ignoring her M.S. degree and years as a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist. Many scientists took Carson’s side, however. President John F. Kennedy appointed a special panel of his Science Advisory Committee to study the issue, and the panel’s 1963 report supported most of Carson’s conclusions.

Rachel Carson died of breast cancer on April 14, 1964. The trend she started, however, did not. It resulted in the banning of DDT in the United States and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Most importantly, it reshaped the way that the American public viewed nature.