Definition

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas. The disease is often multisystem and requires the presence of involvement in two or more organs for a specific diagnosis. The finding of granulomas is not specific for sarcoidosis, and other conditions known to cause granulomas must be ruled out. These conditions include mycobacterial and fungal infections, malignancy, and environmental agents such as beryllium. While sarcoidosis can affect virtually every organ of the body, the lung is most commonly affected. Other organs commonly affected are the liver, skin, and eye. The clinical outcome of sarcoidosis varies, with remission occurring in over half the patients within a few years of diagnosis; however, the remaining patients develop a chronic disease that lasts for decades.

Etiology

Despite multiple investigations, the cause of sarcoidosis remains unknown. Currently, the most likely etiology is an infectious or noninfectious environmental agent that triggers an inflammatory response in a genetically susceptible host. Among the possible infectious agents, careful studies have shown a much higher incidence of Propionibacter acnes in the lymph nodes of sarcoidosis patients compared to controls. An animal model has shown that P acnes can induce a granulomatous response in mice similar to sarcoidosis. Other studies support the possibility of an atypical mycobacterium, although these have yet to be confirmed by blinded studies with adequate controls. Recent studies have demonstrated the presence of a mycobacterial protein [Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase-peroxidase (mKatG)] in the granulomas of some sarcoidosis patients. This protein is very resistant to degradation and may represent the persistent antigen in sarcoidosis. Environmental exposures to insecticides and mold have been associated with an increased risk for disease. In addition, health care workers appear to have an increased risk. Some authors have suggested that sarcoidosis is not due to a single agent but represents a particular host response to multiple agents. An interesting approach to finding the etiology of sarcoidosis is to correlate the environmental exposures to genetic markers. These studies have supported the hypothesis that a genetically susceptible host is a key factor in the disease.

Incidence and Prevalence

Sarcoidosis is seen worldwide, with the highest prevalence reported in the Nordic population. In the United States, the disease has been reported more commonly in blacks than whites, with the ratio of blacks to whites ranging from 3:1 to 17:0.Women appear to be slightly more susceptible than men. The lower estimate is the result of a recent study from a large health maintenance organization in Detroit. The earlier American studies finding the higher incidence in blacks may have been influenced by the fact that blacks seem to develop more extensive and chronic pulmonary disease. Since most sarcoidosis clinics are run by pulmonologists, a selection bias may have occurred. Worldwide, the prevalence of the disease varies from 20-60 per 100,000 for many groups such as Japanese, Italians, and American whites. Higher rate occurs in Ireland and Nordic countries. In one closely observed community in Sweden, the lifetime risk for developing sarcoidosis was 3%.

Sarcoidosis often occurs in young, otherwise healthy adults. It is uncommon to diagnose the disease in someone under age 18. However, it has become clear that a second peak in incidence develops around age 60. In a study of >700 newly diagnosed sarcoidosis patients in the United States, half the patients were ^40 years at the time of diagnosis.

Although most cases of sarcoidosis are sporadic, a familial form of the disease exists. At least 5% of patients with sarcoidosis will have a family member with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis patients who are Irish or American blacks seem to have a two to three times higher rate of familial disease.

Pathophysiology and Immunopathogenesis

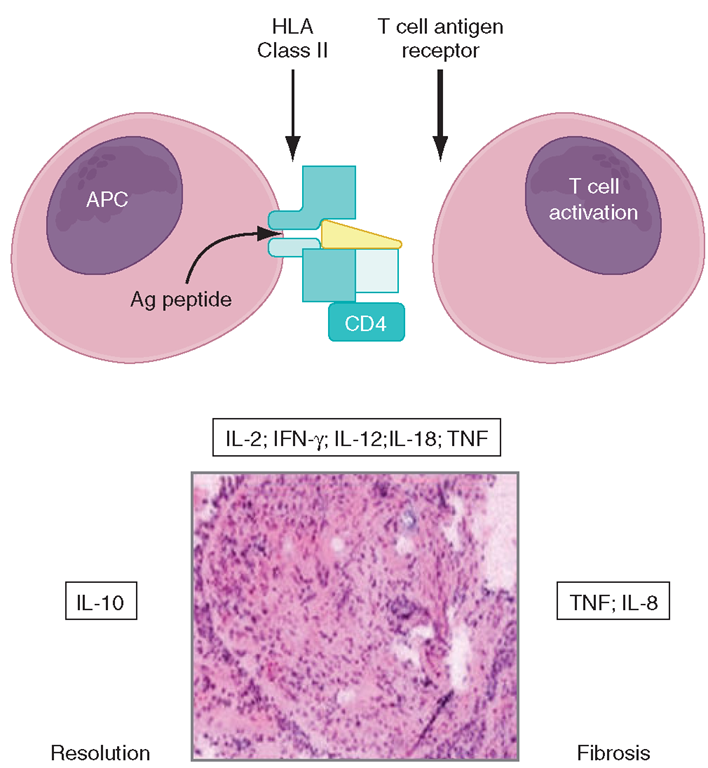

The granuloma is the pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis. A distinct feature of sarcoidosis is the local accumulation of inflammatory cells. Extensive studies in the lung using bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) have demonstrated that the initial inflammatory response is an influx ofT helper cells. In addition, there is an accumulation of activated monocytes. Figure 13-1 is a proposed model for sarcoidosis. Using the HLA-CD4 complex, antigen-presenting cells present an unknown antigen to the helper T cell. Studies have clarified that specific HLA haplotypes such as HLA-DRB1*1101 are associated with an increased risk for developing sarcoidosis. In addition, different HLA haplo-types are associated with different clinical outcomes.

The macrophage/helper T cell cluster leads to activation with the increased release of several cytokines. These include interleukin (IL) 2 released from the T cell and interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) released by the macrophage. The T cell is a necessary part of the initial inflammatory response. In advanced, untreated HIV infection, patients who lack helper T cells rarely develop sarcoidosis. In contrast, several reports confirm that sarcoidosis becomes unmasked as HIV-infected individuals receive antiretroviral therapy, with subsequent restoration of their immune system. In contrast, treatment of established pulmonary sarcoidosis with cyclosporine, a drug that downregulates helper T cell responses, seems to have little impact on sarcoidosis.

FIGURE 13-1

Schematic representation of initial events of sarcoidosis.

The antigen-presenting cell and helper T cell complex leads to the release of multiple cytokines. This forms a granuloma. Over time, the granuloma may resolve or lead to chronic disease, including fibrosis.

The granulomatous response of sarcoidosis can resolve with or without therapy. However, in at least 20% of patients with sarcoidosis, a chronic form of the disease develops. This persistent form of the disease is associated with the secretion of high levels of IL-8.Also, studies have reported that in patients with this chronic form of disease, excessive amounts of TNF are released in the areas of inflammation.

It is sometimes difficult to determine early on the ultimate clinical outcome of sarcoidosis. One form of the disease, Löfgren’s syndrome, consists of erythema nodosum, hilar adenopathy on chest roentgenogram, and uveitis. Löfgren’s syndrome is associated with a good prognosis, with >90% of patients experiencing disease resolution within 2 years. Recent studies have demonstrated that the HLA-DQB1*0201 is highly associated with Löfgren’s syndrome. In contrast, patients with the disfiguring skin condition lupus pernio or cardiac or neurologic involvement rarely experience disease remission.

Clinical Manifestations

The presentation of sarcoidosis ranges from patients who are asymptomatic to those with organ failure. It is unclear how often sarcoidosis is asymptomatic. In countries where routine chest roentgenogram screening is performed, 20-30% of pulmonary cases are detected in asymptomatic individuals. The inability to screen for other asymptomatic forms of the disease would suggest that as many as a third of sarcoidosis patients are asymptomatic.

Respiratory complaints including cough and dyspnea are the most common presenting symptoms. In many cases, the patient presents with a 2-4 week history of these symptoms. Unfortunately, due to the nonspecific nature of pulmonary symptoms, the patient may see physicians for up to a year before a diagnosis is confirmed. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is usually only suggested when a chest roentgenogram is performed.

Symptoms related to cutaneous and ocular disease are the next two most common complaints. Skin lesions are often nonspecific. However, since these lesions are readily observed, the patient and treating physician are often led to a diagnosis. In contrast to patients with pulmonary disease, patients with cutaneous lesions are more likely to be diagnosed within 6 months of symptoms.

Nonspecific constitutional symptoms include fatigue, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Fatigue is perhaps the most common constitutional symptom that affects these patients. Given its insidious nature, patients are usually not aware of the association with their sarcoidosis until their disease resolves.

The overall incidence of sarcoidosis at the time of diagnosis and eventual common organ involvement are summarized in Table 13-1. Over time, skin, eye, and neurologic involvement seem more apparent. In the United

TABLE 13-1

|

FREQUENCY OF COMMON ORGAN INVOLVEMENT AND LIFETIME RISKa |

||

|

|

PRESENTATION, %h |

FOLLOW-UP, %c |

|

Lung |

95 |

94 |

|

Skin |

24 |

43 |

|

Eye |

12 |

29 |

|

Extrathoracic |

15 |

16 |

|

lymph node Liver |

12 |

14 |

|

Spleen |

7 |

8 |

|

Neurologic |

5 |

16 |

|

Cardiac |

2 |

3 |

aPatients could have more than one organ involved.

hFrom ACCESS study of 736 patients evaluated within 6 months of

diagnosis.

cFrom follow-up of 1024 sarcoidosis patients seen at the University of Cincinnati Interstitial Lung Disease and Sarcoidosis Clinic from 2002-2006.

States, the frequency of specific organ involvement appears 1 to be affected by age, race, and gender. For example, eye disease is more common among blacks. Under the age of 40, it occurs more frequently in women. However, in those diagnosed over the age of 40, eye disease is more common in men.

Lung

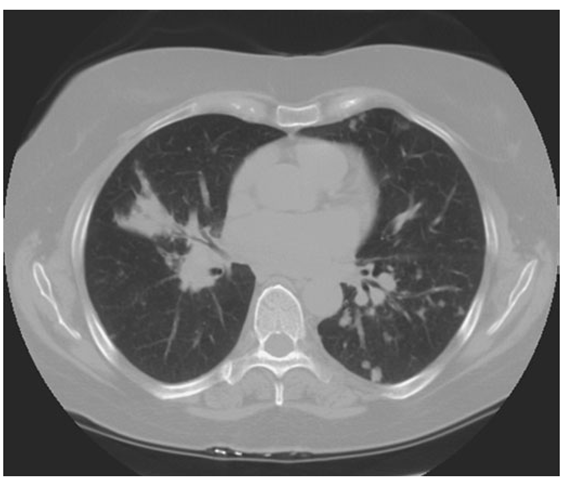

Lung involvement occurs in >90% of sarcoidosis patients. The most commonly used method for detecting lung disease is still the chest roentgenogram. Figure 13-2 illustrates the chest roentgenogram from a sarcoidosis patient with bilateral hilar adenopathy. Although the CT scan has changed the diagnostic approach to interstitial lung disease, the CT scan is not usually considered a monitoring tool for patients with sarcoidosis. Figure 13-3 demonstrates some of the characteristic CT features, including peribronchial thickening and reticular nodular changes, which are predominantly subpleural. The peribronchial thickening seen on CT scan seems to explain the high yield of granulomas from bronchial biopsies performed for diagnosis.

While the CT scan is more sensitive, the standard scoring system described by Scadding in 1961 for chest roentgenograms remains the preferred method of characterizing the chest involvement. Stage 1 is hilar adenopathy alone (Fig. 13-2), often with right paratracheal involvement. Stage 2 is a combination of adenopathy plus infiltrates, whereas stage 3 reveals infiltrates alone. Stage 4 consists of fibrosis. Usually the infiltrates in sarcoidosis are predominantly an upper lobe process. Only in a few non-infectious diseases is an upper lobe predominance noted.

In addition to sarcoidosis, the differential diagnosis of upper lobe disease includes hypersensitivity pneumonitis, silicosis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. For infectious diseases, tuberculosis and Pneumocystis pneumonia can often present as upper lobe diseases.

FIGURE 13-2

Posterior-anterior chest roentgenogram demonstrating bilateral hilar adenopathy, stage 1 disease.

FIGURE 13-3

High-resolution CT scan of chest demonstrating patchy reticular nodularity, including areas of confluence.

Lung volumes, mechanics, and diffusion all are useful in evaluating interstitial lung diseases such as sarcoidosis. The diffusion of carbon monoxide (DLCO) is the most sensitive test for an interstitial lung disease. Reduced lung volumes are a reflection of the restrictive lung disease seen in sarcoidosis. However, a third of the patients presenting with sarcoidosis still have lung volumes within the normal range, despite abnormal chest roentgenograms and dyspnea.

Approximately half of sarcoidosis patients present with obstructive disease, reflected by a reduced ratio of forced vital capacity expired in time interval t (FEVt/FVC). Cough is a very common symptom. Airway involvement causing varying degrees of obstruction underlies the cough in most sarcoidosis patients. However, airway hyperreactivity as determined by metha-choline challenge will be positive in some of these patients. A few patients with cough will respond to traditional bronchodilators as the only form of treatment. In some cases, high-dose inhaled glucocorticoids alone are useful.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is reported in at least 5% of sarcoidosis patients. Either direct vascular involvement or the consequence of fibrotic changes in the lung can lead to pulmonary arterial hypertension. In sarcoidosis patients with end-stage fibrosis awaiting lung transplant, 70% will have pulmonary arterial hypertension. This is a much higher incidence than that reported for other fibrotic lung diseases. In less advanced, but still symptomatic patients pulmonary arterial hypertension has been noted in up to 50% of the cases. Because sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension may respond to therapy, evaluation for this should be considered in persistently symptomatic patients.

Skin

Skin involvement is eventually identified in over a third of patients with sarcoidosis. The classic cutaneous lesions include erythema nodosum, maculopapular lesions, hyper- and hypopigmentation, keloid formation, and subcutaneous nodules. A specific complex of involvement of the bridge of the nose, the area beneath the eyes, and the cheeks is referred to as lupus pernio (Fig. 13-4) and is diagnostic for a chronic form of sarcoidosis.

In contrast, erythema nodosum is a transient rash that can be seen in association with hilar adenopathy and uveitis (Löfgren’s syndrome). Erythema nodosum is more common in women and in certain self-described demographic groups including Caucasians and Puerto Ricans. In the United States, the other manifestations of skin sarcoidosis, especially lupus pernio, are more common in blacks than whites.

The maculopapular lesions from sarcoidosis are the most common chronic form of the disease (Fig. 13-5). These are often overlooked by the patient and physician, since they are chronic and not painful. Initially, these lesions are usually purplish papules elevated up to 1 cm and <3 cm in diameter. They can become confluent and infiltrate large areas of the skin. With treatment, the color and induration may fade. Because these lesions are caused by noncaseating granulomas, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be readily made by a skin biopsy.

FIGURE 13-4

Chronic inflammatory lesions around nose, eyes, and cheeks, referred to as lupus pernio.

FIGURE 13-5

Maculopapular lesions on the trunk of a sarcoidosis patient.