Rheumatologic Evaluation of the Elderly

The incidence of rheumatic diseases rises with age, such that 58% of those >65 years will have joint complaints. Musculoskeletal disorders in elderly patients are often not diagnosed because the signs and symptoms may be insidious, overlooked, or overshadowed by comorbidities. These difficulties are compounded by the diminished reliability of laboratory testing in the elderly, who often manifest nonpathologic abnormal results. For example, the ESR may be misleadingly elevated, and low-titer positive tests for rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) may be seen in up to 15% of elderly patients. Although nearly all rheumatic disorders afflict the elderly, certain diseases and drug-induced disorders (Table 17-2) are more common in this age group. The elderly should be approached in the same manner as other patients with musculoskeletal complaints, but with an emphasis on identifying the potential rheumatic consequences of medical comorbidities and therapies. OA, osteoporosis, gout, pseudogout, polymyalgia rheumatica, vasculitis, drug-induced SLE, and chronic salicylate toxicity are all more common in the elderly than in other individuals. The physical examination should identify the nature of the musculoskeletal complaint as well as coexisting diseases that may influence diagnosis and choice of treatment.

Physical Examination

The goal of the physical examination is to ascertain the structures involved, the nature of the underlying pathology, the functional consequences of the process, and the presence of systemic or extraarticular manifestations. Knowledge of topographic anatomy is necessary to identify the primary site(s) of involvement and differentiate articular from nonarticular disorders. The musculoskeletal examination depends largely on careful inspection, palpation, and a variety of specific physical maneuvers to elicit diagnostic signs (Table 17-3).For such joints, there is a greater reliance upon specific maneuvers and imaging for assessment.

Examination of involved and uninvolved joints will determine whether pain, warmth, erythema, or swelling is present. The locale and level of pain elicited by palpation or movement should be quantified. One example would be to count the number of tender joints on palpation of 28 easily examined joints [proximal interpha-langeals (PIPs), metacarpophalangeals (MCPs), wrists, elbows, shoulders, and knees] (with a range of 0-28). Similarly, the number of swollen joints (0-28) can be counted and recorded. Careful examination should distinguish between true articular swelling (caused by synovial effusion or synovial proliferation) and nonarticular (or periarticular) involvement, which usually extends beyond the normal joint margins. Synovial effusion can be distinguished from synovial hypertrophy or bony hypertrophy by palpation or specific maneuvers. For example, small to moderate knee effusions may be identified by the “bulge sign” or “ballottement of the patellae.” Bursal effusions (e.g., effusions of the olecranon or prepatellar bursa) are often focal, periarticular, overlie bony prominences, and are fluctuant with sharply defined borders. Joint stability can be assessed by palpation and by the application of manual stress.

TABLE 17-3

|

GLOSSARY OF MUSCULOSKELETAL TERMS |

|

Crepitus |

|

A palpable (less commonly audible) vibratory or crackling sensation elicited with joint motion; fine joint crepitus is common and often insignificant in large joints; coarse joint crepitus indicates advanced cartilaginous and degenerative changes (as in osteoarthritis) |

|

Subluxation |

|

Alteration of joint alignment such that articulating surfaces incompletely approximate each other |

|

Dislocation |

|

Abnormal displacement of articulating surfaces such that the surfaces are not in contact |

|

Range of motion |

|

For diarthrodial joints, the arc of measurable movement through which the joint moves in a single plane |

|

Contracture |

|

Loss of full movement resulting from a fixed resistance caused either by tonic spasm of muscle (reversible) or to fibrosis of periarticular structures (permanent) |

|

Deformity |

|

Abnormal shape or size of a structure; may result from bony hypertrophy, malalignment of articulating structures, or damage to periarticular supportive structures |

|

Enthesitis |

|

Inflammation of the entheses (tendinous or ligamentous insertions on bone) |

|

Epicondylitis |

|

Infection or inflammation involving an epicondyle |

Subluxation or dislocation, which may be secondary to traumatic, mechanical, or inflammatory causes, can be assessed by inspection and palpation.Joint swelling or volume can be assessed by palpation. Distention of the articular capsule usually causes pain and evident swelling. The patient will attempt to minimize the pain by maintaining the joint in the position of least intraar-ticular pressure and greatest volume, usually partial flexion. For this reason, inflammatory effusions may give rise to flexion contractures. Clinically, this may be detected as fluctuant or “squishy” swelling, voluntary or fixed flexion deformities, or diminished range of motion—especially on extension, when joint volumes are decreased. Active and passive range of motion should be assessed in all planes, with contralateral comparison. Serial evaluations of the joints should record the number of tender and swollen joints and the range of motion, using a goniometer to quantify the arc of movement. Each joint should be passively manipulated through its full range of motion (including, as appropriate, flexion, extension, rotation, abduction, adduction, lateral bending, inversion, eversion, supination, pronation, medial/lateral deviation, plantar- or dorsiflexion). Limitation of motion is frequently caused by effusion, pain, deformity, or contracture. If passive motion exceeds active motion, a periarticular process (e.g., tendon rupture or myopathy) should be considered. Contractures may reflect antecedent synovial inflammation or trauma. Joint crepitus may be felt during palpation or maneuvers and may be especially coarse in OA. Joint deformity usually indicates a long-standing or aggressive pathologic process. Deformities may result from ligamentous destruction, soft-tissue contracture, bony enlargement, ankylosis, erosive disease, or subluxation. Examination of the musculature will document strength, atrophy, pain, or spasm. Appendicular muscle weakness should be characterized as proximal or distal. Muscle strength should be assessed by observing the patient’s performance (e.g., walking, rising from a chair, grasping, writing). Strength may also be graded on a 5-point scale: 0 for no movement; 1 for trace movement or twitch; 2 for movement with gravity eliminated; 3 for movement against gravity only; 4 for movement against gravity and resistance; and 5 for normal strength. The examiner should assess for often-overlooked nonartic-ular or periarticular involvement, especially when articular complaints are not supported by objective findings referable to the joint capsule.The identification of soft-tissue/nonarticular pain will prevent unwarranted and often expensive additional evaluations. Specific maneuvers may reveal common nonarticular abnormalities, such as a carpal tunnel syndrome (which can be identified by Tinel’s or Phalen’s sign). Other examples of soft-tissue abnormalities include olecranon bursitis, epicondylitis (e.g., tennis elbow), enthesitis (e.g., Achilles tendinitis), and trigger points associated with fibromyalgia.

Approach to Regional Rheumatic Complaints

Although all patients should be evaluated in a logical and thorough manner, many cases with focal musculoskeletal complaints are caused by commonly encountered disorders that exhibit a predictable pattern of onset, evolution, and localization; they can often be diagnosed immediately on the basis of limited historic information and selected maneuvers or tests. Although nearly every joint could be approached in this manner, the evaluation of four common involved anatomic regions—the hand, shoulder, hip, and knee—are reviewed here.

Hand Pain

Focal or unilateral hand pain may result from trauma, overuse, infection, or a reactive or crystal-induced arthritis. By contrast, bilateral hand complaints commonly suggest a degenerative (e.g., OA), systemic, or inflammatory/immune (e.g., RA) etiology.

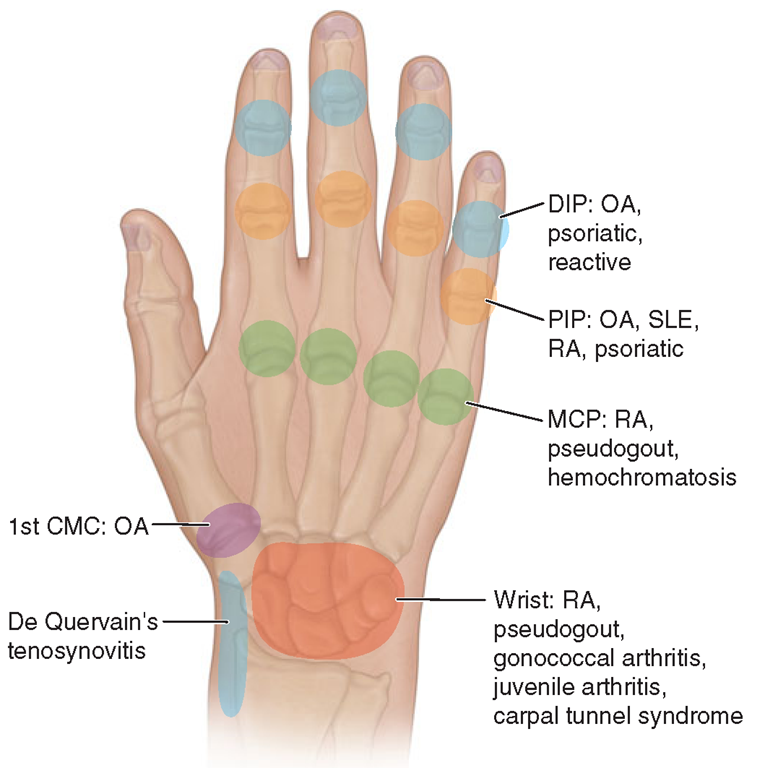

FIGURE 17-4

Sites of hand or wrist involvement and their potential disease associations. (DIP, distal interphalangeal; OA, osteoarthritis; PIP, proximal interphalangeal; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; CMC, carpometacarpal.)

The distribution or pattern of joint involvement is highly suggestive of certain disorders (Fig. 17-4). Thus, OA (or degenerative arthritis) may manifest as distal interphalangeal (DIP) and PIP joint pain with bony hypertrophy sufficient to produce Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes, respectively. Pain, with or without bony swelling, involving the base of the thumb (first carpometacarpal joint) is also highly suggestive of OA. By contrast, RA tends to involve the PIP, MCP, intercarpal, and carpometacarpal joints (wrist) with pain, prolonged stiffness, and palpable synovial tissue hypertrophy. Psoriatic arthritis may mimic the pattern of joint involvement seen in OA (DIP and PIP joints), but can be distinguished by the presence of inflammatory signs (erythema, warmth, synovial swelling), with or without carpal involvement, nail pitting or onycholysis. Hemochromatosis should be considered when degenerative changes (bony hypertrophy) are seen at the second and third MCP joints with associated chondrocalcinosis or episodic, inflammatory wrist arthritis.

Soft-tissue swelling over the dorsum of the hand and wrist may suggest an inflammatory extensor tendon tenosynovitis possibly caused by gonococcal infection, gout, or inflammatory arthritis (e.g., RA).The diagnosis is suggested by local warmth, swelling, or pitting edema and may be confirmed when pain is induced by maintaining the wrist in a fixed, neutral position and flexing the digits distal to the MCP joints to stretch the extensor tendon sheaths.

Focal wrist pain localized to the radial aspect may be caused by De Quervain’s tenosynovitis resulting from inflammation of the tendon sheath(s) involving the abductor pollicis longus or extensor pollicis brevis (Fig. 17-4). This commonly results from overuse or follows pregnancy and may be diagnosed with Finkelstein’s test. A positive result is present when radial wrist pain is induced after the thumb is flexed and placed inside a clenched fist and the patient actively deviates the hand downward with ulnar deviation at the wrist. Carpal tunnel syndrome is another common disorder of the upper extremity and results from compression of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel. Manifestations include paresthesia in the thumb, second and third fingers, and radial half of the fourth finger and, at times, atrophy of thenar musculature. Carpal tunnel syndrome is commonly associated with pregnancy, edema, trauma, OA, inflammatory arthritis, and infiltrative disorders (e.g., amyloidosis). The diagnosis is suggested by a positive Tinel’s or Phalen’s sign.With each test, paresthesia in a median nerve distribution is induced or increased by either “thumping” the volar aspect of the wrist (Tinel’s sign) or pressing the extensor surfaces of both flexed wrists against each other (Phalen’s sign).

Shoulder Pain

During the evaluation of shoulder disorders, the examiner should carefully note any history of trauma, fibromyalgia, infection, inflammatory disease, occupational hazards, or previous cervical disease. In addition, the patient should be questioned as to the activities or movement(s) that elicit shoulder pain. Shoulder pain is referred frequently from the cervical spine but may also be referred from intrathoracic lesions (e.g., a Pancoast tumor) or from gall bladder, hepatic, or diaphragmatic disease. Fibromyalgia should be suspected when glenohumeral pain is accompanied by diffuse periarticular (i.e., subacromial, bicipital) pain and tender points (i.e., trapezius or supraspinatus).The shoulder should be put through its full range of motion both actively and passively (with examiner assistance): forward flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation. Manual inspection of the periarticular structures will often provide important diagnostic information. The examiner should apply direct manual pressure over the subacromial bursa that lies lateral to and immediately beneath the acromion. Subacromial bursitis is a frequent cause of shoulder pain. Anterior to the subacromial bursa, the bicipital tendon traverses the bicipital groove. This tendon is best identified by palpating it in its groove as the patient rotates the humerus internally and externally.

Direct pressure over the tendon may reveal pain indicative of bicipital tendinitis. Palpation of the acromioclavicular joint may disclose local pain, bony hypertrophy, or, uncommonly, synovial swelling. Whereas OA and RA commonly affect the acromioclavicular joint, OA seldom involves the glenohumeral joint, unless there is a traumatic or occupational cause. The glenohumeral joint is best palpated anteriorly by placing the thumb over the humeral head (just medial and inferior to the coracoid process) and having the patient rotate the humerus internally and externally. Pain localized to this region is indicative of glenohumeral pathology. Synovial effusion or tissue is seldom palpable but, if present, may suggest infection, RA, or an acute tear of the rotator cuff.

Rotator cuff tendinitis or tear is a very common cause of shoulder pain. The rotator cuff is formed by the tendons of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis muscles. Rotator cuff tendinitis is suggested by pain on active abduction (but not passive abduction), pain over the lateral deltoid muscle, night pain, and evidence of the impingement sign. This maneuver is performed by the examiner raising the patient’s arm into forced flexion while stabilizing and preventing rotation of the scapula. A positive sign is present if pain develops before 180° of forward flexion. A complete tear of the rotator cuff is more common in the elderly and often results from trauma; it may manifest in the same manner as tendinitis but is less common. The diagnosis is also suggested by the drop arm test in which the patient is unable to maintain the arm outstretched once it is passively abducted. If the patient is unable to hold the arm up once 90° of abduction is reached, the test is positive. Tendinitis or tear of the rotator cuff can be confirmed by MRI or ultrasound.

Knee Pain

A careful history should delineate the chronology of the knee complaint and whether there are predisposing conditions, trauma, or medications that might underlie the complaint. For example, patellofemoral disease (e.g., OA) may cause anterior knee pain that worsens with climbing stairs. Observation of the patient’s gait is also important. The knee should be carefully inspected in the upright (weight-bearing) and prone positions for swelling, erythema, contusion, laceration, or malalignment. The most common form of malalignment in the knee is genu varum (bowlegs) or genu valgum (knock knees). Bony swelling of the knee joint commonly results from hypertrophic osseous changes seen with disorders such as OA and neuropathic arthropathy. Swelling caused by hypertrophy of the synovium or synovial effusion may manifest as a fluctuant, ballotable, or soft-tissue enlargement in the suprapatellar pouch (suprapatellar reflection of the synovial cavity) or regions lateral and medial to the patella.

Synovial effusions may also be detected by balloting the patella downward toward the femoral groove or by eliciting a “bulge sign.” With the knee extended the examiner should manually compress, or “milk,” synovial fluid down from the suprapatellar pouch and lateral to the patellae. The application of manual pressure lateral to the patella may cause an observable shift in synovial fluid (bulge) to the medial aspect. The examiner should note that this maneuver is only effective in detecting small to moderate effusions (<100 mL). Inflammatory disorders such as RA, gout, pseudogout, and reactive arthritis may involve the knee joint and produce significant pain, stiffness, swelling, or warmth. A popliteal or Baker’s cyst is best palpated with the knee partially flexed and is best viewed posteriorly with the patient standing and knees fully extended to visualize popliteal swelling or fullness.

Anserine bursitis is an often missed periarticular cause of knee pain in adults. The pes anserine bursa underlies the semimembranosus tendon and may become inflamed and painful following trauma, overuse, or inflammation. It is often tender in patients with fibromyalgia. Anserine bursitis manifests primarily as point tenderness inferior and medial to the patella and overlies the medial tibial plateau. Swelling and erythema may not be present. Other forms of bursitis may also present as knee pain. The prepatellar bursa is superficial and is located over the inferior portion of the patella. The infrapatellar bursa is deeper and lies beneath the patellar ligament before its insertion on the tibial tubercle.

Internal derangement of the knee may result from trauma or degenerative processes. Damage to the menis-cal cartilage (medial or lateral) frequently presents as chronic or intermittent knee pain. Such an injury should be suspected when there is a history of trauma or athletic activity and when the patient relates symptoms of “locking,” clicking, or “giving way” of the joint. Pain may be elicited during palpation over the ipsilateral joint line or when the knee is stressed laterally or medially. A positive McMurray test may indicate a meniscal tear. To perform this test, the knee is first flexed at 90°, and the leg is then extended while the lower extremity is simultaneously torqued medially or laterally. A painful click during inward rotation may indicate a lateral meniscus tear, and pain during outward rotation may indicate a tear in the medial meniscus. Lastly, damage to the cruciate ligaments should be suspected with acute onset of pain, possibly with swelling, a history of trauma, or a synovial fluid aspirate that is grossly bloody. Examination of the cruciate ligaments is best accomplished by eliciting a drawer sign. With the patient recumbent, the knee should be partially flexed and the foot stabilized on the examining surface. The examiner should manually attempt to displace the tibia anteriorly or posteriorly with respect to the femur. If anterior movement is detected, then anterior cruciate ligament damage is likely. Conversely, significant posterior movement may indicate posterior cruciate damage. Contralateral comparison will assist the examiner in detecting significant anterior or posterior movement.

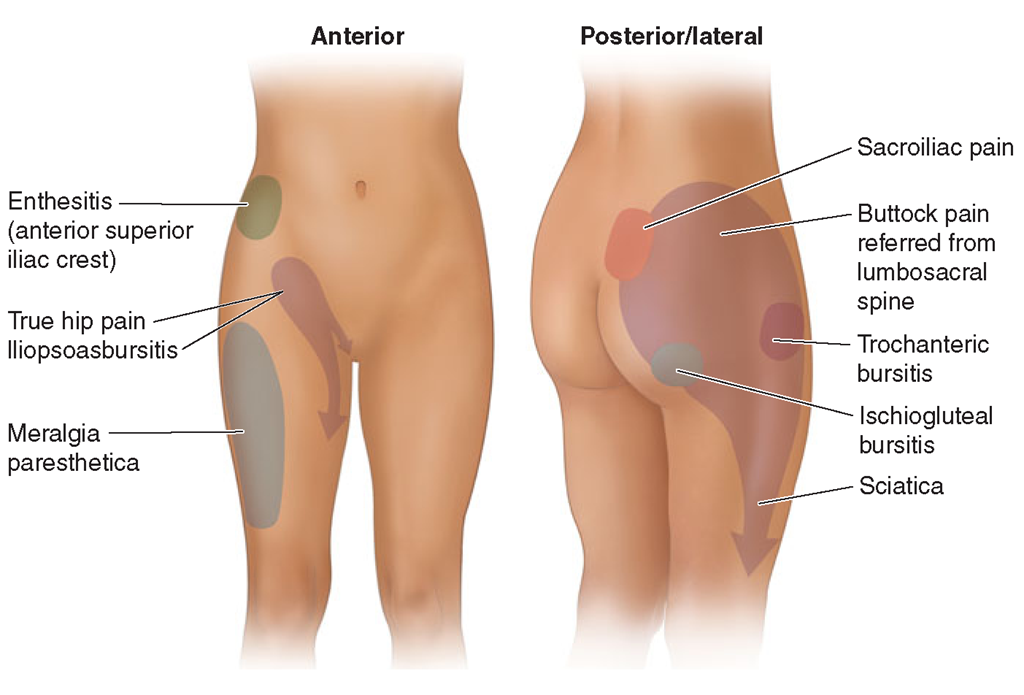

FIGURE 17-5

Origins of hip pain and dysesthesias.

Hip Pain

The hip is best evaluated by observing the patient’s gait and assessing range of motion. The vast majority of patients reporting “hip pain” localize their pain unilaterally to the posterior or gluteal musculature (Fig. 17-5). Such pain may or may not be associated with low back pain and tends to radiate down the posterolateral aspect of the thigh. This presentation frequently results from degenerative arthritis of the lumbosacral spine and commonly follows a der-matomal distribution with involvement of nerve roots between L5 and S1. Some individuals instead localize their “hip pain” laterally to the area overlying the trochanteric bursa. Because of the depth of this bursa, swelling and warmth are usually absent. Diagnosis of trochanteric bursitis can be confirmed by inducing point tenderness over the trochanteric bursa. Gluteal and trochanteric pain may also indicate underlying fibromyalgia. Range of movement may be limited by pain. Pain in the hip joint is less common and tends to be located anteriorly, over the inguinal ligament; it may radiate medially to the groin or along the antero-medial thigh. Uncommonly, iliopsoas bursitis may mimic true hip joint pain. Diagnosis of iliopsoas bursitis may be suggested by a history of trauma or inflammatory arthritis. Pain associated with iliopsoas bursitis is localized to the groin or anterior thigh and tends to worsen with hyperextension of the hip; many patients prefer to flex and externally rotate the hip to reduce the pain from a distended bursa.