(1911-1993)

The man once known to his readers as “the Dumas of the pulps,” Richard Sale was one of the top journeymen writers in the 1930s and 1940s. He was not a superstar like Max brand or Edgar Rice burroughs, but his name was on countless magazine covers in the golden age of the pulps. Sale guaranteed to developers a reliable supply of first-rate fiction and to readers the certainty of an hour or two well spent. He was barely out of his teens when his name started appearing in Detective Fiction Weekly, Dime Detective, Argosy, Bluebook, Thrilling Mystery, Double Detective, and more.

“From the start . . . even as a small kid,” he told this author, “I sold some stuff to the New York Herald Tribune. Poems, and I mean bad. But I had no other ambition except to write.” Sale studied journalism at Washington and University, in Lexington, Virginia. While still at school, he began sending out stories to magazines. He sold one to Street & Smith’s College Stories: “I got $100 and that was a lot of money in those Depression days.” He sold a second story with a school setting, and then got nothing but rejections for two years. He left school before graduating, got married, and worked for a couple of New York newspapers, but mostly devoted himself to trying to make a living from his fiction. Before long it happened. His stories for the pulps started selling—and selling. In a 10-year period Sale published around 500 stories, nearly one a week. But at his busiest, Sale’s schedule was actually more grueling than that. “A story a day. A story was 3,000 words, 5,000 words. It depended how it flowed. I’d do it in a day, sometimes it carried over to the next day. If you were doing novelettes, that would be 12,000 words and that would carry over into the next day . . . First draft was a last draft,” he said. Sale took his place among the speed demons of the pulps, the legendary million-words-a-year men like Brand, Arthur J. Burks, and Lester dent. Sale wrote mysteries, exotic adventures, horror and terror tales, air war stories, and sea stories week after week, throughout the depression and into the first years of World War II. “You couldn’t sit around and wait for ideas to come. Sometimes you’d sit there and just look around the room and pick an object . . . Or think of something impossible and then solve it.” Sale was such a reliable storytelling machine at this time that an editor thought nothing of grabbing him in the hallway as he was leaving the developer’s office and demanding a publishable story on the spot: “He needed a story in a hurry. Emergency. So he sat me down and I knocked out a 3,000-word story. I came up with a story about what goes through a man’s mind when he drifts down in a parachute. Turned out to be a good story. I gave him the story, went to the window and they issued me a check right then and there and I went home.”

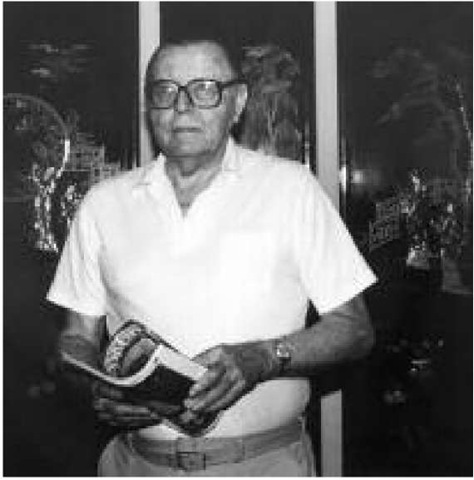

Richard Sale, “the Dumas of the pulps”

Sale became best known to pulp readers for his series of stories about a tough-talking newspaperman, Joe “Daffy” Dill. Pulp writers were always looking to get a series going. “If a character caught on,” he recalled, “then you knew they would ask for more. A popular series sold a lot of copies. They’d get letters from readers asking for more about so-and-so.” Sale had some firsthand knowledge of the big city news hawks of the day, and built upon the popular archetype of the front page reporter—tough, fast-moving, wisecracking, amiably ruthless. Published by Detective Fiction Weekly, the Dill stories (occasionally supplemented by spinoff stories about Dill’s Weegee-like pal, photographer Candid Jones) were told in a first-person, vernacular voice, and moved like lightning. Until the final shootout and crime-solving denouement, nearly all of Dill’s narration and dialogue was slangy sarcasm—he even answers the phone with a bantering, “Your nickel!” This sort of thing was done to death in the detective pulps, but Sale’s brash skill kept the Dill stories fresh and funny.

Concurrent with his pulp work load, Sale began writing novels. The first, published in 1936, was a tale of hard-bitten prisoners escaping from Devil’s Island, Not Too Narrow, Not Too Deep, a strange combination of hard-boiled adventure and evangelism. “My wife was a Christian Scientist then,” Sale told me. “Not I, I was barely a Christian in that sense. But I took the core of what she believed and applied it . . . to make a positive Christian story. People have always said the character was supposed to be Jesus. I said no, it was about one Christian practicing Christianity.” The novel is a forgotten classic of early hard-boiled writing, memorable right from the terse, haunting first paragraph:

Nine out of ten of those coast fishermen who put in at St. Pierre and offer escape are rascals. I remember the horror I felt when I first learned that they trafficked in other men’s misery. They’d offer their boat for your escape. When you got on it and put out to sea they’d stab you in the back, and when you were dead they’d disembowel you, cut out the metal capsule with your precious money, and throw your body overboard where the sharks and barracuda made short work of it. You have to hide your money in your body, you see, because that is the only safe place you have.

Sale moved to Hollywood, hoping to break into the movies as a screenwriter. In the meantime he wrote a series of fast-paced crime novels with a film background. Sale used all the cliched ingredients of the popular Hollywood mystery, but he gave them an imaginative reshuffling. Lazarus No. 7 concerned a murderous movie star with leprosy and a studio doctor who resurrects dead dogs in his spare time. In Passing Strange, Sale took the notion of shallow Hollywood to new heights of black humor: when a surgeon is shot dead while performing a Ce-sarean section on a “two-time Oscar winner,” all the tinseltown press corps wants to know about is the celebrity mother and her new kid.

As he had hoped, Sale did find work in the movies. He and his then wife Mary Loos—a niece of the legendary pioneering screenwriter and bon vivant Anita Loos—peddled scripts to Republic and then Fox studios. Sale, a charismatic fellow with movie-star good looks himself, made a steady pursuit of big studio success and was soon producing and directing films as well as writing them. His first film, a Technicolor comedy western called A Ticket to Tomahawk (1950), contained an early appearance by Marilyn Monroe. Subsequent films that Sale directed were mostly light-hearted entertainments (for example, Gentlemen Marry Brunettes) (1955). He wrote but did not direct Suddenly, a tense suspense picture with Frank Sinatra as a would-be presidential assassin. His last directorial effort, and his best, was not light-hearted at all. Abandon Ship (1957) was a harrowing variation on Hitchcock’s 1944 film Lifeboat. Shot entirely on an English sound stage, Sale’s film managed to fully convey the agony of shipwreck survivors in an open sea. Under Sale’s direction, Tyrone Power, as the wretched ship’s captain forced to choose who must live and who must die, gave the best performance of his career.

Sale made a return to fiction with an inside look at sleazy Hollywood, a best-selling novel called The Oscar (which became a risible motion picture of the same name starring Stephen Boyd and Elke Sommer). He continued writing topics and movies to the end of his life. His epic spy novel, For the President’s Eyes Only, was masterful, as was his wintry western adventure, White Buffalo (which he subsequently adapted for the film version with Charles Bronson). He has been unfairly neglected in pop cultural chronicles in favor of pulpsters, crime writers, and filmmakers with a fraction of his talent. Sale’s was a remarkable ca-reer—a half-century of interesting, varied, and entertaining work.

Works

- Benefit Performance (1946);

- Cardinal Rock (1940);

- Destination Unknown (also published as Death at Sea) (1943);

- For the President’s Eyes Only (1971);

- Home Is the Hangman (1949);

- Is a Ship Burning (1937);

- Lazarus No. 7 (1942);

- Murder at Midnight (1950);

- Not Too Narrow, Not Too Deep (1936);

- Oscar, The (1963);

- Passing Strange (1942);

- Sailor, Take Warning (1942);

- White Buffalo (1980)