1. Background

Most economists know from personal experience that their perspective on the economy is unpopular. When they teach introductory students or write a basic textbook, one of their main goals is to correct students’ misconceptions. What makes this task easier is that students usually share the same misconceptions. They resist the standard critique of price controls, doubt the benefits of free trade, and believe the economy is in secular decline. What makes this task harder, though, is that students usually resist efforts to correct their misconceptions. Even if they learn the material to pass the final exam, only a fraction are genuinely convinced. The position of the modern economic educator is, moreover, far from novel. The 19th-century experiences of Frederic Bastiat in France (1964) and Newcomb (1893) in the United States mirror those of Jeffrey Sachs (1994) in 20th-century Russia.

What often lends urgency to the economic educators’ mission is their sense that the popularity of mistaken economic beliefs leads democracies to adopt foolish economic policies. The world could be much better off if only the man in the street came to understand what economists already know. Bastiat exemplifies this mentality when he explains that bad economics… guides our cabinet ministers only because it prevails among our legislators; it prevails among our legislators only because they are representative of the electorate; and the electorate is imbued with it only because public opinion is saturated with it. (1964, p. 27)

Paul Samuelson put an optimistic spin on the same idea: "I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws — or crafts its advanced treaties — if I can write its economics textbooks." (Nasar, 1995, C1).

So there is a long tradition in economics of (a) recognizing systematic belief differences between economists and the public, and (b) blaming policy failures on these belief differences. In spite of its pedigree, however, this tradition is largely ignored in modern academic research in economics in general and public choice in particular. Most models of political failure assume that political actors — voters included — have a correct understanding of economics. Models that emphasize imperfect information still normally assume that agents’ beliefs are correct on average (Coate and Morris, 1995). Even though this assumption runs counter to most economists’ personal experience, it has received surprisingly little empirical scrutiny.

2. Evidence

Numerous surveys investigate the economic beliefs of the general public or economists. (Alston et al., 1992; Fuchs et al., 1998; Shiller et al., 1991; Walstad and Larsen, 1992; Walstad, 1997) These tend to confirm economists’ unofficial suspicions, but only indirectly. To the best of my knowledge, there is only one study that deliberately asks professional economists and members of the general public identical questions on a wide variety of topics. That study is the Survey of Americans and Economists on the Economy (1996, henceforth SAEE; Blendon et al., 1997), which queried 250 Ph.D. economists and 1,510 randomly selected Americans.

The SAEE overwhelmingly confirms the existence of large systematic belief differences between economists and the public. The differences are significant at the 1% level for 34 out of 37 questions (Caplan, 2002). Moreover, the signs of the disagreements closely match common stereotypes. The public is much more pessimistic about international trade, much more concerned about downsizing and technological unemployment, much more suspicious of the market mechanism, and much less likely to believe that the economy grew over the past twenty years. Stepping back, there appear to be four main clusters of disagreement: anti-foreign bias, make-work bias, anti-market bias, and pessimistic bias.

3. Anti-foreign Bias

On any economic issue where foreigners are involved, the public tends to see exploitation rather than mutually advantageous trade. Thus, most of the public claims that "companies sending jobs overseas" is a "major reason" why the economy is not doing better; very few economists agree. The same holds for immigration: most economists see it as a non-problem, but almost no non-economists concur. Similarly, even though economists have often criticized foreign aid, few see it as a serious problem for the U.S. economy, for the simple reason that foreign aid is a minis-cule fraction of the federal budget. A large majority of the public, in contrast, sees foreign aid as a heavy drain on donor economies.

4. Make-work Bias

Unlike economists, the general public almost sees employment as an end in itself, an outlook Bastiat (1964) memorably derided as "Sisyphism." They are accordingly distressed when jobs are lost for almost any reason. Economists, in contrast, see progress whenever the economy manages to produce the same output with fewer workers. Thus, economists generally view downsizing as good for the economy, an idea non-economists utterly reject. Economists do not worry about technological unemployment; the public takes this possibility fairly seriously. It is tempting to think that this gap stems from different time horizons (economists look at the long-run, non-economists at the short-run), but the data go against this interpretation. Even when asked about the effects of new technology, foreign competition, and downsizing twenty years in the future, a massive lay-expert gap persists.

5. Anti-market Bias

What controls market prices? Economists instinctively answer "supply and demand," but few non-economists believe so. Fully 89% of economists explain the 1996 oil price spike using standard supply and demand; only 26% of the public does the same. Non-economists tend to attribute higher prices to conspiracies rather than market forces. In a similar vein, economists see profits and executive pay as vital incentives for good performance. Most of the public, in contrast, looks upon the current level of profits and executive pay as a drag on economic performance. Overall, the public has little sense of the invisible hand, the idea that markets channel human greed in socially desirable directions.

6. Pessimistic Bias

Economists think that economic conditions have improved and will continue to do so. The public sees almost the opposite pattern: they hold that living standards declined over the past two decades, and doubt whether the next generation will be more prosperous than the current one. In addition, the public thinks the economy is beset by severe problems that most economists see as manageable: the deficit, welfare dependency, and high taxes, to take three examples.

7. Robustness

A particularly nice feature of the SAEE is that it includes an array of details about respondents’ characteristics. This makes it possible to not only test for systematic belief differences, but to test various hypotheses attempting to explain them. This is particularly important because critics of the economics profession often argue that for one reason or another, the public is right and the "experts" are wrong.

Some critics point to economists’ self-serving bias. (Blendon et al., 1997) Economists have large incomes and high job security. Perhaps their distinctive beliefs are the result of their personal circumstances. Do economists think that "What is good for economists is good for the country"? It turns out that there is little evidence in favor of this claim. Ceteris paribus, income level has no effect on economic beliefs at all, and job security only a minor one. High-income non-economists with tenure think like normal members of the public, not economists.

Other critics point to economists’ conservative ideological bias. (Greider, 1997; Soros, 1998) The truth, though, is that the typical economist is a moderate Democrat. Controlling for party identification and ideology tends if anything to increase the size of the belief gap between economists and the public. It is true, of course, that economists endorse a variety of extremely conservative views on downsizing, profits, tax breaks, and the like. What their critics fail to appreciate, though, is that economists endorse almost as many extremely liberal views on subjects like immigration and foreign aid.

Admittedly, these empirical tests only show that economists are not deluded because of self-serving or ideological bias. It is logically possible that economists are mistaken for a presently unknown reason. Like myself, moreover, the reader probably disagrees with economists’ conventional wisdom on some point or other. Still, the two leading efforts to discredit the economics profession empirically fail. At this point it is reasonable to shift the burden of proof to the critics of the expert consensus.

8. What Makes People Think like Economists?

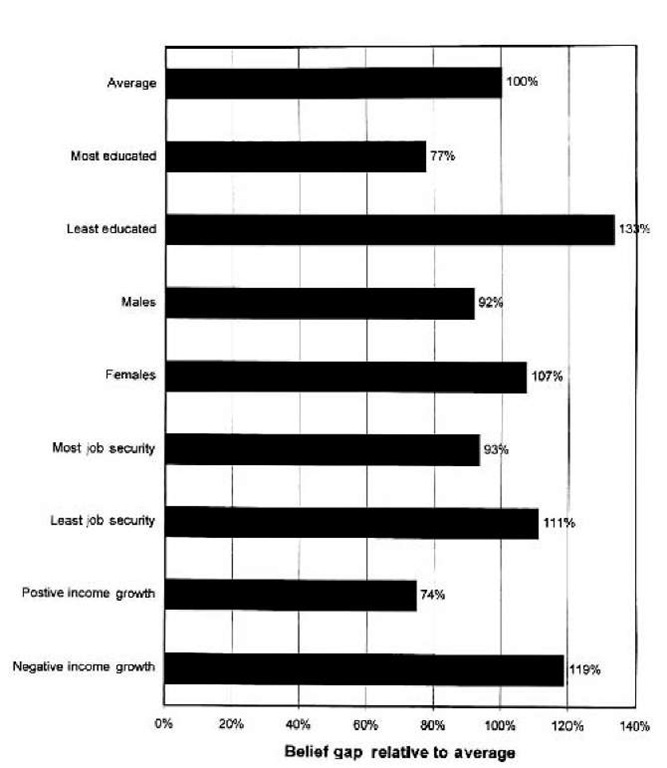

While virtually every segment of the general population has large disagreements with economists, some segments disagree more than others. Education, being male, income growth, and job security consistently make people think more like economists; income level and ideological conservatism do not. Caplan (2001) uses the SAEE data to construct a scalar measure of the magnitude of disagreement with economists’ consensus judgments. Figure 1 summarizes the results: The first bar shows that belief gap between economists and the average member of the general public; the other bars show how the belief gaps of other segments of the population compare. For example, the belief gap between economists and the most-educated non-economists is only 77% as large as the belief gap between economists and non-economists with the average level of education.

9. Policy Significance

The SAEE results suggest a simple explanation for why economists find so much fault with government policy: Most voters do not understand economics, and vote for politicians and policies in harmony with their confusion.

Figure 1: Size of belief gaps between economists and population sub-groups.

(Caplan forthcoming). The long history of protection and the uphill battle for free trade can be seen as an outgrowth of anti-foreign bias. Make-work bias favors labor market regulation; few non-economists recognize the potential impact on employment. The periodic imposition of price controls is unsurprising given the strength of the public’s anti-market bias. Pessimistic bias is more difficult to link directly to policy, but seems like a fertile source for an array of ill-conceived policy crusades.

One question that often vexes economists is "Why isn’t policy better than it is?" Popular answers include special interests, corruption, and political collusion. If you take the evidence on the economic beliefs of the public seriously, however, the real puzzle instead becomes "Why isn’t policy far worse?" Part of the explanation is that the well-educated are both more likely to vote and somewhat more in agreement with the economic way of thinking. But this is far from a complete account. Figuring out the rest is one of the more interesting challenges facing the next generation of political economists.