Historical evidence speaks with a single voice on the relation between political freedom and a free market. I know of no example in time or place of a society that has been marked by a large measure of political freedom that has not also used something comparable to a free market to organize the bulk of economic activity. (Friedman, 1962, p. 9)

History suggests only that capitalism is a necessary condition for political freedom. Clearly it is not a sufficient condition (Friedman, 1962, p. 10)

Economic freedom refers to the quality of a free private market in which individuals voluntarily carry out exchanges in their own interests. Political freedom means freedom from coercions by arbitrary power including the power exercised by the government. Political freedom consists of two basic elements: political rights and civil liberties. Sufficient political rights allow people to choose their rulers and the way in which they are ruled. The essence of civil liberties is that people are free to make their own decisions as long as they do not violate others’ identical rights. Friedman (1962) points out the historical fact that economic freedom and political freedom are inextricably connected. However, the relationships among economic freedom, civil liberties, and political rights are complex (Friedman, 1991).

In a free private market, individuals have the freedom to choose what to consume, to produce, and to give. The invisible hand leads free economic agents to pursue their own interests and voluntarily cooperate with others (Smith, 1776). Economic freedom and civil liberties are clearly related. A society whose civil liberties are incomplete is unlikely to sustain a free private market since civil liberties and economic freedom have in common the freedom from coercions by other individuals or governments. A free private market is characterized by voluntary transactions among individuals who are left alone to pursue their own ends for their economic objectives. The value of political freedom to economic freedom exactly lies in the fact that civil liberties are defined as including guarantees to limit governmental power and to protect individual autonomy. Human freedom embedded in civil liberties is the means through which economic freedom is realized.

The importance of political rights to economic freedom, however, is less clear. Friedman (1991) points out that "political freedom, once established, has a tendency to destroy economic freedom." He basically believes that the process of political competition, as determined by political rights, may generate policies that negatively affect economic freedom. Public choice scholars have long argued that competitively elected politicians and their agents in the bureaucracy are self interested and may intervene and disturb the free market to please their constituencies and sponsors. Individuals enjoying political rights use democratic forms of government to redistribute wealth from others often by interfering with the free market, by restricting competition or limiting sales through the manipulation of prices, or otherwise creating rents. The misuse of political freedom in democracies has caused an expansion of services and activities by governments far beyond the appropriate scope in which economic and human freedoms are protected and maintained. Inefficiencies of democracy fundamentally impose constraints on the workings of a free private market and hamper the full realization of economic freedom (see Buchanan and Tullock, 1962; Buchanan et al., 1980;Tullock et al., 2000).

A democracy, once established, tends to limit economic freedom to some degree. More surely, an authoritarian regime is less likely to positively promote economic freedom. Suppose that a country develops a political system with a hierarchically structured bureaucratic organization that gives privileges to an elite class. In such a country, political freedom must be restricted to serve the elite minority. Even if a market exists, it must not be a true free private market. Individuals are merely agents of the state and cannot be truly competitive. Moreover, political authorities in an authoritarian regime tend to distort the market by allocating resources by coercion. The elite class controls a large part of the resources and effectively controls the entire spectrum of economic decisions. Economic freedom develops and evolves by accident, and never by design (Hayek, 1944).

Historically and logically, it is clear that economic freedom is a condition for political freedom. A core ingredient of economic freedom is private property which is fundament in supporting political freedom. Without secure private property and independent wealth, the exercise of political rights and civil liberties loses its effectiveness. Hayek (1944) maintains that "Economic control is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest: it is the control of the means for all our ends." People who depend on the government for their employment and livelihood have little capacity to oppose the government as they exercise their political rights. Without rights to own and utilize their properties as they want, people cannot operate a free media, practice their religions, and so forth.

In the long term, economic freedom leads to and sustains political freedom. It is no doubt that a free private market is most conducive to wealth creation (Smith, 1776). A system of economic freedom is superior to any system of planning and government management (Hayek, 1944). The market process is a spontaneous order in which resources are efficiently allocated according to individual needs voluntarily expressed by people. Without any coercions and deliberate designs, a free private market brings about economic efficiency and greater social welfare. The wealth effects of economic freedom create necessary social conditions for political freedom. Fundamentally, an authoritarian regime that represses political freedom cannot survive alongside a free private market in the long run. A free private market not only is a process for achieving the optimal allocation of resources and creating wealth, which provides material foundations for political freedom, but also provides an environment for learning and personality development that constructs behavioral foundations for political freedom. However, whether or not these conditions would lead to democracies depends on other complex factors, especially, the strategic interactions among various political groups (Przeworski, 1992).

Relations among economic freedom, civil liberties, and political rights are complex theoretically and historically. To empirically assess these relations, we face a hurdle of measuring economic and political freedom. Fortunately, several serious efforts on measuring the freedoms have recently been made. Particularly impressive are those measurements with regular upgrades. Rich panel data sets of economic and political freedoms make it possible to test various hypotheses developed in the vast theoretical literature on the two freedoms and to inspire future theoretical development based on insights derived from empirical analyses.

1. Measuring Economic Freedom

The first attempt to measure economic freedom was undertaken by Gastil and his associates at Freedom House (Gastil, 1982). Economic freedom rankings were compiled to complement Freedom House’s political freedom rankings. Soon two major economic freedom indexes were published by the Heritage Foundation and the Fraser Institute (Johnson and Sheehy, 1995; Gwartney et al., 1999). The Fraser Institute and the Heritage Foundation have updated their indexes regularly. We focus on comparing the Fraser Index and the Heritage Foundation Index.

Both the Fraser Index and the Heritage Foundation Index attempt to obtain an overall economic freedom ranking for each country during a particular year based on raw scores on a variety of factors relevant to economic freedom. They follow a similar procedure that contains the following elements: defining economic freedom; selecting component variables; rating component variables; combining component ratings into the final overall rankings of economic freedom.

The Fraser Index defines core ingredients of economic freedom as personal choice, protection of private property, and freedom of exchange. In the Heritage Foundation Index, "economic freedom is defined as the absence of government coercion or constraint on the production, distribution, or consumption of goods and services beyond the extent necessary for citizens to protect and maintain liberty itself" (O’Driscoll et al., 2002). Both definitions reflect the essence of a free private market. They represent an ideal state in which a limited government focuses on protecting private property rights and safeguarding the private market for individuals to freely engage in exchanges.

Guided by their definitions of economic freedom, the two Indexes identify areas that are relevant to economic freedom. The Fraser Index selects 21 components under seven areas: size of government; economic structure and use of markets; monetary policy and price stability; freedom to use alternative currencies; legal structure and security of private ownership; freedom to trade with foreigners; and freedom of exchange in capital markets. The Heritage Foundation Index chooses fifty variables in ten factors: trade policy; the fiscal burden of government; government intervention in the economy; monetary policy; capital flows and foreign investment; banking and finance; wages and prices; property rights; regulations; and black market activity. Apparently, the two Indexes attempt to cover essential features of economic freedom: protection of private property; reliance on the private market to allocate resources; free trade; sound money; and limited government regulations.

The two Indexes differ significantly in ways in which they rate on components of economic freedom. The Heritage Foundation Index uses a five-level grading scale to determine scores for each factor based on information collected on pertinent factor variables. However, not all factor variables are individually graded. Therefore, raw data on factor variables are combined into factor grades in a relatively subjective way. There are no explicit formulas for summarizing information on factor variables into factor grades. The Fraser Index directly assigns scores to all component variables on a 0-to-10 scale. For continuous component variables, the Fraser Index applies explicit and fixed formulas to convert original data on component variables into scores. For categorical component variables, subjective judgments are applied to obtain scores. Areas of economic freedom in the Fraser Index are rated solely on the scores of pertinent component variables. In comparison, scores on the factors in the Heritage Foundation Index seem to be obtained in a more subjective way than scores on areas in the Fraser Index. However, this practice allows the Heritage Foundation Index more liberty in using a wider range of information sources. The Heritage Foundation Index not only has more factor variables, but also covers more countries and time periods.

The two Indexes also differ in their weighting schemes for combining component ratings into their final overall rankings of economic freedom. The Heritage Foundation Index simply weights factor ratings equally. The Fraser Index uses principle component analysis to construct weights for each component variables in calculating the final scores of economic freedom.The method suits well for the exercise of measuring economic freedom since the final overall scores of economic freedom are derived from components that are assumed to reflect some aspects of the concept of economic freedom. The weights are based on the principal component that explains the maximum variations in the original data of component variables among all standardized linear combinations of the original data.

The Fraser Index claims to develop an objective measure of economic freedom. It is transparent and objective in scoring component variables and weighting component ratings in the final index of economic freedom. Nevertheless, these solid steps in the procedure do not change the qualitative nature of a measure of economic freedom. An economic freedom measure is not quantitative data such as national income that can be truly objectively measured. The usefulness of an economic freedom measure lies in the fact that it provides rankings of different countries over time. In other words, final scores of economic freedom are ordinal in nature. The Heritage Foundation Index applies four categories of economic freedom: Free, Mostly Free, Mostly Unfree, Repressed. The Fraser Index does not provide qualitative categories like this. Final ratings in the Fraser Index range from 0 to 10, with a higher number indicating higher degree of economic freedom. We ought not to mistake these ratings as continuous and cardinal data. The only valid and usable information in these ratings is the relative degrees of economic freedom indicated by the scores. For example, in 1997, the Fraser Index gives Hong Kong a score of 9.4, Albania 4.3, and Chile 8.2. From these numbers, we can only conclude that Hong Kong is freest economically among the three, Chile second, and Albania third. The difference between any two scores cannot be interpreted numerically. For example, we cannot say that Hong Kong is 119% freer than Albania.

The two Indexes share some similarities and some differences in their methods of measuring economic freedom. We are interested in whether the different methods would lead to differences in their final ratings of economic freedom. To statistically compare the two Indexes, we compile a data set which includes 238 country-years in 1995 and 1999. The two Indexes overlap in these two years.1 We use data of the four categories in the Heritage Foundation Index, and accordingly collapse the inherent ten rankings (based upon the 0-10 scale) into four categories based on the final rankings in the Fraser Index.2 Table 1 shows a cross-classification of economic freedom in the Heritage Foundation Index by that in the Fraser Index. Table 1 clearly demonstrates a pattern in which observations classified as economically freer in the Heritage Foundation Index are also classified as economically freer in the Fraser Index.

Table 1: Cross-classification of Heritage Foundation Index by Fraser Index

|

Fraser Index |

Heritage Foundation Index |

|

|

Repressed Mostly unfree Mostly free |

Free |

|

|

Repressed |

5 10 0 |

0 |

|

Mostly Unfree |

8 56 14 |

0 |

|

Mostly Free |

0 27 79 |

3 |

|

Free |

0 0 14 |

22 |

The two Indexes classify observations similarly. Among the observations in Table 1, the total number of concordant

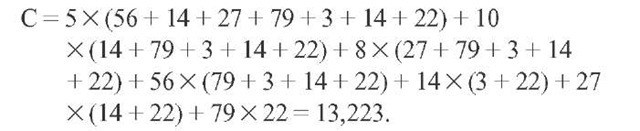

• 3 • pairs3 is:

The number of discordant pairs of observations is: D = 10 X 8 + 14 X 27 + 3 X 14 = 500.

Of the concordant and discordant pairs, 96.36% are concordant and only 3.64% are discordant. The difference of the corresponding proportions gives a gamma (= (C – D)/ (C + D) = 92.72%).

The number indicates that the Heritage Foundation Index and the Fraser Index are highly correlated. We can further explore the relationship between the two Indexes by testing the null hypothesis of independence between the two categorical variables. We simply use a Pearson chi-squared test and a likelihood-ratio chi-squared test to analyze the cross-classification as shown in Table 1. The Pearson chi-squared statistic is 218.43 which yields a P-value less than 0.0001, and the likelihood-ratio chi-squared statistic is 197.49 with a P-value less than 0.0001 (based on degree of freedom = 9). There is very strong evidence of association between these two measures even if we ignore the category orderings of the variables.4

2. Measuring Political Freedom

The concept of political freedom and democracy is much debated. Our task here is not to provide an exhaustive review of the debates, but to point out empirical conceptions of political freedom and democracy that cover its main features in the modern world that are relevant to statistical analyses. These narrow definitions of political freedom and democracy enable us to identify empirical cases of democracies and non-democracies. Dahl (1971) provides a useful definition of democracy by emphasizing the procedural characteristics of the political system. Democracy, as an institutional arrangement, ought to ensure the following conditions:

1. Freedom to form and join organizations;

2. Freedom of Expression;

3. Right to vote;

4. Eligibility for public office;

5. Right of political leaders to compete for support (Rights of political leaders to compete for votes);

6. Alternative sources of information;

7. Free and fair elections;

8. Institutions for making government policies depend on votes and other expressions of preferences.

When these conditions are met, the elected government is judged to be responsive to citizens’ preferences, and the democracy and political freedom are established

Dahl’s eight conditions describe the core of a modern democracy. For the purpose of empirically measuring political freedom, however, we need to further condense the definition and establish rules that can help categorize observations unambiguously. There exist several empirical measurements, and there is no agreement among scholars regarding the ways of actually measuring democracy (Bollen, 1980, 1993; Vanhanen, 1990; Przeworski et al., 2000; Mainwaring et al., 2001). However, Przeworski et al. (2000) point out . even if regime classification has been the subject of some controversies, alternative definitions of "democracy" give rise to almost identical classifications of actual observations.

We want to compare two representative measurements.5 One is by Freedom House and the other by Przeworski et al. (2000) (PACL, hereafter). The two measurements are both rule-based in the sense that both apply pre-determined criteria in identifying democracies. Nonetheless, Freedom House and PACL appear to represent the two "extremes" of measuring political freedom and democracy. Freedom House’s political freedom rankings are based on raw scores assigned by experts, and hence, seem to be subjective. PACL’s political regime classification exclusively relies on observables, and attempts to avoid subjective judgments.

Freedom House first differentiates two basic dimensions of political democracy: political rights and civil liberties. The former mainly refers to the electoral process. Elections should be fair and meaningful (choices of alternative parties and candidates, and a universal franchise). The latter implies freedom of the press, freedom of speech, freedom of religious beliefs, and the right to protest and organize. The Freedom House measure is comprehensive and related to multiple dimensions of a modern democracy. Its focus is not the form of government itself, but upon political rights and the freedom of citizens caused by the real working of the political system and other societal factors. To contrast, the PACL measure is concerned with political regimes as forms of government, and focuses on contestation as the essential feature of democracy. The authors intentionally exclude political freedom from their measurement. The narrow definition by PACL is aimed to avoid using different aspects of democracy (e.g., as defined by Dahl, 1971) that the authors believe to be of little use. The authors argue "Whereas democracy is a system of political rights — these are definitional — it is not a system that necessarily furnishes the conditions for effective exercise of these rights." (Przeworski et al. 2000) Whether or not democracy as narrowly defined by PACL is associated with political rights and other desirable aspects of democracy is a question for empirical testing.6

Different concepts and scopes of political freedom put forward by Freedom House and PACL underpin their rules and criteria for classifying democracies. Freedom House assigns each country the freedom status of "Free," "Partly Free," and "Not Free" based on their ratings in political rights and civil liberties. To rate political rights and civil liberties in a country, Freedom House employs two series of checklists for these two aspects of democracy. For political right ratings, Freedom House uses eight checklist questions and two discretionary questions. These questions are not only related to formal electoral procedures but also other non-electoral factors that affect the real distribution of political power in a country. Freedom House’s civil liberties checklist includes four sub-categories (Freedom of Expression and Belief, Association and Organizational Rights, Rule of Law and Human Rights) and fourteen questions in total. Freedom House maintains that it does not mistake formal constitutional guarantees of civil liberties for those liberties in practice.

While the civil liberties component is broadly conceived, the political rights dimension of the Freedom House measure is more compatible with PACL’s rules for regime classification.7 These rules exclusively deal with electoral contestation and government selections. The three basic rules are labeled as "executive selection," "legislative selection," and "party." The idea is to identify democracies as regimes in which the chief executive and the legislature are elected in multi-party elections. The great majority of cases (91.8% of country-years in PACL’s sample) are unambiguously classified by the three rules. PACL further introduces an additional rule ("alternation") for those ambiguous cases. The "alternation" rule is used to classify countries that have passed the three basic rules. In these countries, the same party or party coalition had won every single election from some time in the past until it was deposed by force or until now. For these cases, we face two possible errors: excluding some regimes that are in fact democracies from the set of classified democracies (type I error); including some regimes that are not in fact democratic in the set of classified democracies (type II error). PACL seeks to avoid type-II errors. Therefore, there are some regimes that meet the three basic criteria which are disqualified as democracies.

PACL rigidly and mechanically applies these four rules, but Freedom House rates countries with discretion. To be "unbiased," PACL only needs to strictly adhere to their rules while Freedom House needs to consciously maintain a culturally unbiased view of democracy and utilize the broadest range of information sources. The PACL measure is necessarily consistent because it exclusively relies on observables and objective criteria. Freedom House’s checklists and ratings procedures are consistent. However, the ratings themselves could be inconsistent because of variation in information sources, raters’ expertise and so on.

The distinctive spirits of the Freedom House and PACL measures are nicely reflected in their timing rules. Both measures observe countries in a period of a year. PACL codes the regime that prevails at the end of the year. Information about the real situation before the end of the year is not relevant. For example, a country that has been a democracy until the last day of a year is classified as a dictatorship in the PACL measure. For the same country, Freedom House would treat it differently and consider the political development during the whole year and assign appropriate scores. The information lost in the PACL measure is utilized in the Freedom House ratings, and the loss of information is significant for some cases, especially for many countries in political transition.

The categorization of political regimes in the PACL measure could be nominal in the sense that there is no ordering between democracy and dictatorship, or ordinal that a transition from dictatorship to democracy means some improvement. PACL’s further classifications of democracy and dictatorship are nominal in nature. The difference between parliamentary, mixed, and presidential democracies is meaningful if merely qualitative and definitional. However, the difference between bureaucracy and autocracy could be quantitative. PACL classifies a dictatorship with a legislature as a bureaucracy, and not as an autocracy. Freedom House’s freedom rankings are explicitly ordinal. The overall statuses of "Free," "Partly Free," and "Not Free" reflect different degrees of political freedom in countries. The base scores of political rights and civil liberties ratings are themselves ordinal. Freedom House uses a seven-point scale for the two dimensions of democracy, with 7 indicating the highest degree and 1 the lowest degree. This measurement implicitly assumes that there exists a continuum of political democracy. The two poles are the fully democratic regime (with 1 for both political rights and civil liberties) and a full autocratic regime (with 7 for both political rights and civil liberties). The underlying continuum of political regimes makes it easier to describe and analyze the rich phenomena of political transitions. Freedom House rankings make it possible to analyze the intermediate cases of semi-democracies or semi-dictatorships, and the complicated nature of democratization or reverse-democratization. Under the PACL classification, there are only two possible transition modes: from democracy to dictatorship, and from dictatorship to democracy. The simplified transition modes are less capable of capturing the transitional nature of political development.

To quantitatively compare the Freedom House and PACL measures, we use a data set that consists of 2584 country-years during the period from 1972 to 1990.This data set includes all observations that have both the PACL regime classifications and the Freedom House ratings.8 Table 2 shows a cross-classification of political regime (PACL classifications) by freedom status (the Freedom House overall ratings).

From Table 2, we observe "Not Free" is mostly associated with "Dictatorship", and "Free" with "Democracy". For countries with a "Partly Free" ranking, more are "Dictatorship" than "Democracy". This result probably reflects the cautious stance taken by the PACL measure that tries to avoid type-II errors. Overall, these two measures are quite similar. Among the observations in Table 2, concordant pairs number at 1,361,384, and the number of discordant pairs of observations is 7,773. Thus, 99.43% are concordant and only 0.57% are discordant. The sample gamma is 98.86%. This confirms that a low degree of political freedom occurs with non-democratic regimes and high degree of political freedom with democratic regimes. The Freedom House rankings are highly correlated with PACL political regime measures.9

Table 2: Cross-classification of political regime by freedom status

|

Political freedom |

Political |

regime |

|

Dictatorship |

Democracy |

|

|

Not Free |

931 |

1 |

|

Partly Free |

711 |

106 |

|

Free |

66 |

769 |

We can further explore the relationship between the Freedom House and PACL measures by testing the null hypothesis of independence between the two categorical variables. The Pearson chi-squared statistic is 1896.62, and the likelihood-ratio chi-squared statistic is 2201.61 (based on degree of freedom = 2). Both statistics give P-values less than 0.0001. There is very strong evidence of association between these two measures even if we ignore the category orderings of the variables.

The apparent "anomalies" are cases that are reflected in up-right and bottom-left corner cells. The only one observation that is classified as "Not Free" and "Democracy" is Guatemala in 1981. The Freedom House 1981 volume’s description of Guatemala (p. 352) reports: "Most opposition parties are now heavily repressed…. Military and other security forces maintain decisive extra-constitutional power at all levels: those politicians who oppose them generally retire, go into exile, or are killed." Then the 1982 edition begins its report with the sentence (p. 296): "Until a 1982 coup Guatemala was formally a constitutional democracy on the American model." The PACL measure seems to have classified Guatemala as a democracy in 1981 while Freedom House observers clearly judged the government to be categorized by repression which was confirmed by the 1982 coup.

There are sixty-six cases that are classified as "Free" and "Dictatorship" as shown in Table 3. Among these cases, two third (66.7%) are classified according to "alternation" rules. As pointed out above, the "alternation" rules risk type-I error. So those country-years that are classified as dictatorship could actually be democracies. Using more information and discretion, Freedom House gives these observations a "Free" ranking. Botswana is a typical example. Political stability characterizes Botswana’s political landscape. Botswana’s Democratic Party has been ruling the country until the present. PACL "alternation" rules require Botswana during the period from 1972 to 1990 to be classified as a dictatorship. However, Freedom House rates it as "Partly Free" in 1972 and "Free" in 19 years after that, based on their information sources and survey methodology.

It is interesting to note that all those forty-four cases, in which "alternation" rules are applied, are classified as bureaucracies in PACL’s more detailed regime classification. Actually, the great majority (64 out of 66) of cases rank "Free" in Freedom House surveys are classified as bureaucracies by PACL. Bureaucracies in the PACL measure are those dictatorships with legislatures, and certainly more likely to be ranked at "Free" by Freedom House than those autocracies. Among the sixty-six observations, there are only two cases in which Freedom House ranks them at "Free" and PACL classifies them as "autocracies." In the case of Nigeria, the "anomaly" is due to the timing rules used by PACL. According to Freedom House, Nigeria changed from a multiparty democracy which began in 1979 and began to change after 1982 in a series of coups, rather than a single event, which by 1984 had placed the government under the control of a military command. The judgmental nature of the Freedom House rules caused a slower reclassification.

Table 3: Cases that are classified as dictatorship and free

|

Country |

Period |

Regime |

Alternation rule or not |

|

Botswana |

1973-1990 |

Bureaucracy |

Yes |

|

Burkina Faso |

1978, 1979 |

Bureaucracy |

Yes |

|

Djibouti |

1977,1978 |

Bureaucracy |

No |

|

El Salvador |

1972-1975 |

Bureaucracy |

Yes |

|

Fiji |

1972-1986 |

Bureaucracy |

No |

|

Gambia |

1972-1980, 1989, 1990 |

Bureaucracy |

Yes |

|

Ghana |

1981 |

Autocracy |

No |

|

Guyana |

1972 |

Bureaucracy |

Yes |

|

Malaysia |

1972,1973 |

Bureaucracy |

No |

|

Nigeria |

1983 |

Autocracy |

No |

|

Seychelles |

1976 |

Bureaucracy |

No |

|

Sri Lanka |

1977-1982 |

Bureaucracy |

Yes |

|

West Samoa |

1989, 1990 |

Bureaucracy |

Yes |

There was a military intervention in Ghana in 1979 that led to political executions. However, the 1981 Freedom House review gives the "free" rating and begins with the sentence (p. 350): "Since Fall 1979 Ghana has been ruled by a parliament and president representing competitive parties." The 1982 report changed the rating to "not free" and noted that the country was being ruled by a military faction. It also noted that there had been some political detentions and police brutality before the 1981 coup, but ". such denials of rights have subsequently increased" (p. 295). In this instance the observers from Freedom House seem to have recognized the institution of democracy and classified the Country as "free" in 1981 but in 1982 they not only changed their rating to "not free" but also implicitly corrected their observation of the previous year.

3. Empirical Analyses on Economic Freedom and Political Freedom

With comprehensive data on economic and political freedoms becoming available, there is a surge of empirical studies on the two freedoms and the relationships between freedom and other economic and social variables.

There already existed a vast literature on the influence of political freedom on economic growth before measurements of economic freedom were published. The findings of these empirical studies are conflicting (Pourgerami, 1988; Scully, 1988; Glahe and Vorhies, 1989; Przeworski and Lomongi, 1993; Paster and Sung, 1995; Haan and Siermann, 1996). The empirical results range from positive to negative influences of political freedom on economic growth. The contradictions of the results could be attributed to contrasting model specifications and empirical measurements of political freedom. Some authors argued that the freedom which really matters in economic growth is economic freedom (Scully, 1992; Brunetti and Wedder, 1995; Knack and Keefer, 1995; Barro, 1996). This line of investigation was energized by the publication of the Heritage Foundation Index and the Fraser Index. The Cato Journal published a special issue on "Economic Freedom and the Wealth of Nations" in 1998. Positive effects of economic freedom on growth are also reported in a variety of empirical studies (Easton and Walker, 1997; Ayal and Georgios, 1998; Dawson, 1998; Haan and Siermann, 1998; Gwartney et al., 1999; Wu and Davis, 1999a, b). Economic freedom is also used to explain other aspects of economic development including income equality and human well-being (Berggren, 1999; Esposto and Zaleski, 1999).

Economic freedom as an independent variable in explaining economic growth and development is robust in numerous studies. We conclude that the arguments heard down through the centuries — a reliance upon the market place and unrestrained competition in the allocation of a society’s resources is the best policy to promote economic growth — have largely been established by the experiences of the countries of the world as these have been analyzed by numerous researchers working with these new measurements. It is also the same case for economic development as a significant explanatory variable for democracy. In Lipset’s classic statement, "Perhaps the most wide widespread generalized linking political system to other aspects of society is related to the state of economic development" (Lipset, 1959). Economic development, as an independent variable, has survived in a variety of rigorous empirical tests on determinants of democratic development (Diamond, 1992; Przeworski et al., 2000).

The linkages depicted in these empirical studies relate economic freedom to economic growth, and economic development to political freedom. As noted above, these two links seem to be well established. Moreover, these linkages suggest a less well established empirical the influence of economic freedom on political freedom. Such a link between economic freedom and political freedom would certainly confirm certain theoretical insights in the literature. We judge there to be a need for further studies.

Empirical analyses on the possible reverse relationship between political freedom and economic freedom are largely lacking. We will not speculate upon the reasons for the relative scarcity of studies. We simply note that it is important to learn whether the careful study of our measured history of freedoms will confirm the theoretically based arguments and observations that democracy "inherently" acts to constrain economic freedom, and whether the precise nature of such constraints can be illuminated. Further, these additional analyses are important to verify theoretical arguments about possible conflicting effects of civil liberties and political rights upon each other as well as on economic freedom. Is there a tendency for a free electoral system to work so as to limit civil rights if there is not a developed constitution and independent judiciary to prevent such an action? Do guarantees of civil rights mean that through time an electoral system will necessarily be established? Which, if not both, might be a factor in limiting economic freedom? Finally, will further empirical analyses be able to establish that there exists an endogenous relationship between economic freedom and political freedom?

There are many questions waiting to be answered and empirically established. It may be that the possible endo-goniety between economic and political freedom is one of the most intriguing and perhaps the most important. If a demonstration of endogoniety can include a specification of the mechanism, if the establishment of more economic freedom really tends to lead to the development of democratic forms of government, then there are urgent reasons to hope for and expect additional studies.