The story of U.S. propaganda during World War II can be divided into two phases: a period of neutrality from September 1939 to December 1941, during which a great debate raged among the population at large, and the period of U.S. involvement in the war, when the government mobilized a major propaganda effort through the Office of War Information (OWI). Both phases witnessed a key role being played by the commercial media.

Although Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) was never popular in the United States, the widespread feeling that the U.S. role in World War I had been a mistake cooled American reactions to the outbreak of war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) refused to ask his people to be “neutral in spirit” and called for the revision of U.S. neutrality laws to at least allow war materials to be sold to the Allies. The great neutrality debate began in earnest following the fall of France in June 1940. The pro-Allies lobby consisted of the moderate Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies and an actively interventionist Century Group (later known as the Fight for Freedom Committee). The pro-neutrality position was represented by the America First Committee. The isolationist camp included newspapers—especially those owned by William Randolph Hearst (1863— 1951), the influential Chicago Tribune, and such well-known individuals as Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974). Both sides used rallies, petitions, and demonstrations to advance their causes. In Hollywood the independent producer Walter Wanger (1894-1968) and the Warner Bros. studio released a number of films with a political message, including Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939). Isolationists in the Senate denounced such ventures as propaganda on behalf of Jewish and pro-British vested interests.

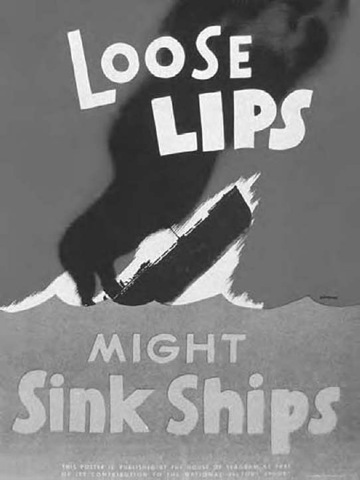

World War II U.S. poster. Every combatant made similar appeals for discretion.

President Roosevelt initially took a backseat in the debate because of the impending presidential election. In December 1940 he demonstrated more active leadership by advancing his “Lend Lease” aid policy through a “fireside chat” over the radio. The Lend-Lease Act, promising “all aid short of war,” passed Congress on March 15, 1941. As part of its policy of rearmament, the Roosevelt administration established a number of propaganda and information organizations, including the Rockefeller Bureau to rally opinion in Latin America (1940); the Office of Government Reports (1939) and Office of Facts and Figures (1940) to present information at home; and the Office of the Coordinator of Information, a new covert intelligence agency that included a propaganda branch. In August 1941 Roosevelt persuaded Churchill to sign the Atlantic Charter, calling for a postwar United Nations and a policy of unconditional surrender. By the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, the debate over U.S. foreign policy had been all but settled.

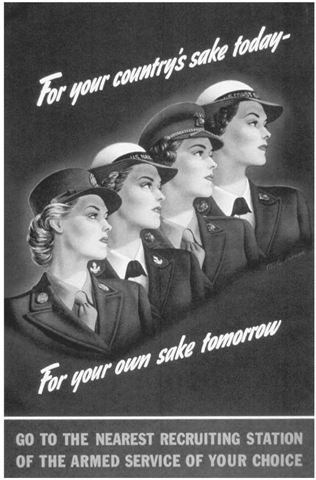

In the summer of 1942 the U.S. government regrouped it various propaganda agencies into a single Office of War Information (OWI), although some psychological operations remained under the new Office of Strategic Services (OSS). OWI tactical campaigns included massive leaflet drops to support the invasion of North Africa in 1942, and special air-dropped newspapers for occupied countries and eventually even enemy territory. Psychological warfare teams advanced alongside U.S. military forces and had considerable success in appealing to the enemy to surrender. At home campaigns conceived in collaboration with the commercial media included an effort to engage women in heavy-duty war work. During this campaign Saturday Evening Post artist Norman Rockwell (1894—1978) created the character of Rosie the Riveter. Some of the most important ideological initiatives came from outside the OWI. In January 1941 Henry Luce (1898— 1967), the editor of Time, wrote an editorial proclaiming the “American Century.” The idea that the time had come for American global leadership gained wide acceptance during the war. Internationalism received a boost from lawyer and Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie (1892-1944) and his book One World (1943). Roosevelt also contributed to the nation’s morale, especially in his definition of Allied war aims. The notion of the Four Freedoms, dating from January 1941 (freedom of speech and of worship, freedom from fear and from want) proved particularly potent both in the United States and around the world. For a highly successful war bond drive Rockwell produced a series of paintings illustrating each of these freedoms.

The United States used propaganda to orient troops (most famously in the U.S. Army Signal Corps film series Why We Fight) and to motivate its civilian population. The approach varied between the European and Pacific theaters. Whereas in Europe the United States depicted the enemy as an evil regime, in Asia the enemy was depicted as an entire race. U.S. war bond posters variously pictured the Japanese as ratlike or simian monsters. U.S. newspaper cartoons took up the theme without official prompting, with the result that the fanatical Japanese soldier became a familiar and enduring stereotype. Parallel Japanese ideas about the West led to a war of mutual extermination on the island battlefields of the Pacific. Propaganda laid the foundation for U.S. use of the atomic bomb against Japan in August 1945.

Recruiting poster for women during World War II.

During the war the U.S. government carefully controlled its use of atrocity stories, a tactic that had been much discredited following World War I. The American public seemed reluctant to believe the first news of Nazi genocide (which came from Jewish and Polish sources), and the U.S. government made little attempt to further publicize the story. The government often released news of Japanese atrocities in a very controlled way—often several months after the events became known—though not in the case of the notorious Bataan Death March, in which thousands of Allied soldiers died on their way to Japanese prisoner-of-war camps.

The extraordinary level of government and commercial propaganda in the United States during the war created a number of myths that crumbled in the postwar period. Joseph Stalin proved to be something less than the avuncular nationalist of U.S. wartime propaganda, nor did Chiang Kai-shek in China live up to his image as the democratic strongman of Asia. In Republican propaganda the apologies for Stalin were seen as evidence of left-wing domination of the Roosevelt administration, and the “loss” of China became evidence that Chiang had been betrayed by an American enemy within. Such claims set the stage for McCarthyism. The apparatus of U.S. wartime propaganda, such as the Voice of America (VOA) radio station, survived the war to become the core of the U.S. propaganda effort in the Cold War. On the battlefield Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) became convinced of the power of the “P” (psychological factor) in warfare and championed the use of propaganda during his presidency.