INTRODUCTION

Many industry sectors are facing a number of challenges to the established relations between players (the automotive sector is a particularly prominent case in point; see also Gerst & Jakobs, 2006). To meet the production requirements, standardization ofprocesses, systems, and data are inevitable. A current trend in manufacturing is that OEMs1 attempt to cooperate with fewer suppliers, but on a worldwide scale.

The use of ICT2 related technologies, particularly ebusiness systems, facilitates the creation of a network of relationships within a supply chain. Yet, such inter-organizational integration requires interoperability that cannot be achieved without widely agreed standards. But how should standards be set, and who has—or should have—a say in the standardization process? In many cases, an SME3 supplier does business with more than one OEM. In this situation, bi-lateral standardization to improve the cooperation between OEMs and suppliers, and between different suppliers, respectively, is inefficient. Still, this has been the approach of choice in many cases.4 However, possible alternatives are available.

In the automotive industry, for example, portals were developed as a form of sector-specific harmonization. Yet, these attempts to develop standardised technology largely failed. This holds particularly for the most prominent example, Covisint. Its failure may be attributed to various technical, organizational, and economic reasons. The main contributing factors, however, included the unequal power distribution during the development process (only the large OEMs had a say; the suppliers were largely left in the cold), and the equally imbalanced distribution of benefits (which mirrored the power distribution). The fact that Covisint was sector-specific probably represented another problem as many suppliers did not only do business within the automotive sector, but with other industries as well (see Gerst et al. (2006) for a far more detailed discussion of this subject).

This rather negative example suggests that perhaps yet another alternative approach should be deployed. One straightforward such alternative would be to take these activities to a dedicated standards organization. After all, portal technology relies heavily on underlying e-business standards such the extended markup language (XML), the UDDI registry (universal description, discovery, and integration), the Web services description language (WSDL), SOAP, and many others. Moreover, many of these organizations offer a more level playing field for smaller companies, certainly in theory (see Jakobs (2004) for a perhaps more realistic view).

BACKGROUND

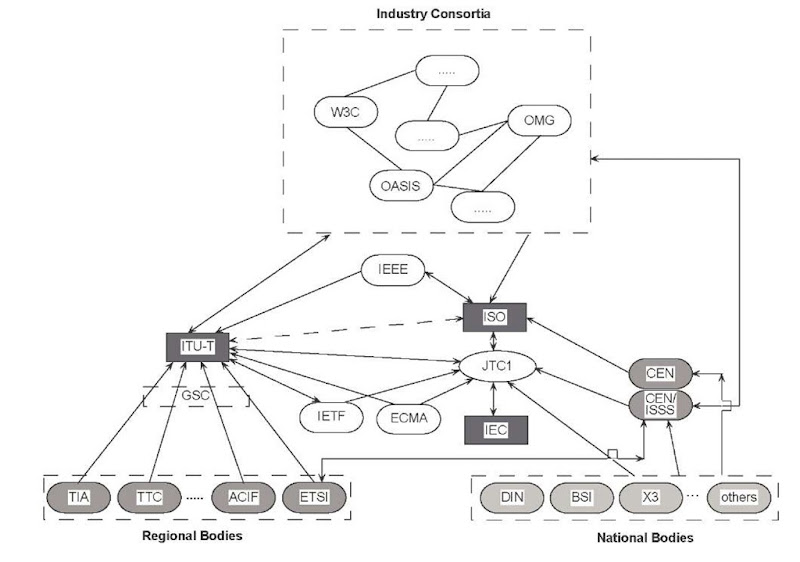

These days, a network of standards developing organizations (SDOs5) operates at various geographical levels. They issue what is commonly referred to as “de-jure” standards—al-though in fact none of their standards has any regulatory power.6 In addition to these formal bodies, a huge number of consortia and industry fora have entered the e-business standards setting arena over the last decades (a recent survey found around 300 (ISSS, 2005)). These organizations produce so-called de-facto standards. Those who develop standards specifically relevant for e-business include for example, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the organization for the advancement of structured information standards (OASIS), and the open group.

As a result of this diversity, companies are faced with an almost impenetrable Web of standards setting bodies (SSBs7) with complex inter-relations. Each of these bodies has its own membership base (frequently overlapping, though), works within a specific environment, and has defined its own set of rules. The resulting fragmentation of the standards-setting arena—and overlap of the activities of individual SSBs—means that interoperability between standards from different sources cannot necessarily be assumed. Accordingly, improving coordination in e-business standards setting has become a major issue. At the same time, however, we observe fierce competition in standards setting.

Standardization had always been the SDOs’ monopoly. However, in the 80s consortia began to emerge, invading the SDOs’ territory. This move was also helped by the deregulation of the telecommunication sector. Eventually, the SDOs started fighting back. As a result, these days competition in ICT/e-business standards setting occurs at different levels, and organization wishing to become active in standards setting need to select the SSB best suited to their specific needs.

COMPETITION IN STANDARDIZATION

Over the last three decades, the proliferation of SSBs has lead to an extremely complex situation in the market for standards in the e-business sector. Figure 1 gives an impression of the situation today (the figure is far from giving the full picture, though).

The emergence of such a huge number of SSBs, often with overlapping coverage, caused a fragmentation of the market for standards development. In addition, the ICT and e-business domains are subdivided into different industry sectors, each of which has specific needs and requirements. Consequently, sector-specific standards are being developed and used, thus further contributing to the fragmentation of the market.

This fragmentation, in turn, triggers competition. Different SSBs covering similar ground are struggling for influence, implementers, and market shares. In the e-business sector—whose standards are highly relevant for any portal development—such competition between SSBs may be observed, for example, in the cases of RosettaNet and ebXML, and for the semantic Web services initiative (SWSI) and the W3C.9

Competition between SSBs implies an element of choice. That is, users may select the one standard (out of a number of competing ones) that best meets their requirements. Analogously, prospective standards setters may select the most promising platform for their activities. The downside, however, is that a wrong choice may easily lead to a negative outcome; a user may be locked in a loosing technology not accepted by the market. Likewise, standards setters may eventually find that the standard they pushed has lost against competitors. Thus, a sensible selection becomes imperative in both cases. In the case of a company wishing to set a new standard, or to influence an emerging one, this process will need to be based on two metrics:

• The role the company wishing to adopt in the standardization process,

• The characteristics of the SSBs.

Companies’ business models and strategies in the ebusiness sector differ widely. In most cases, the respective degree of interest of a company wishing to get involved in a new standards setting activity will differ widely. For some, the nature of a standard, or even the fact that a new standard will materialise, may be a matter of life or death. For others, an emerging new standard may be of only rather more academic interest. Accordingly, prospective participants in a standardization activity may be subdivided into three categories: “leader,” “adopter,” and “observer,” respectively.10 The motivation to actively participate in standards setting, and for joining—or maybe even establishing—an SSB will be very different for members of each individual category, and may be summarised as follows (see also Jakobs & Wallbaum (2005a)):

• Leaders: These are companies for which participation in a certain standards-setting activity is critical. “Leaders” aim to control the strategy and direction of an SSB, rather than to merely participate in its activities. Large vendors, manufacturers, and service providers are typical representatives of this class.

Figure 1. The ICT/e-business standardization universe today

• Adopters: Such companies are less interested in influencing strategic direction and goals of an SSB. Adopters are more interested in participation than influence (although they may well want to influence the technical characteristics of individual standards). Large users, SME vendors and manufacturers, and system integrators may typically be found here.

• Observers: Such companies’ (and individuals’) main motivation for participation is intelligence gathering. Typically, this group comprises, for instance, small companies in niche markets, academics, and consultants.

Similarly, SSBs can be categorised according to very different criteria. The most popular, albeit not particularly helpful distinction is between formal SDOs and consortia. Typically, the former are said to be slow, compromise-laden, and in most cases not able to deliver on time what the market really needs. In fact, originally the formation of consortia was seen as one way of avoiding the allegedly cumbersome processes of the SDOs, and to deliver much needed standards on time and on budget. Consortia have been widely perceived as being more adaptable to a changing environment, able to enlist highly motivated and thus effective staff, and to have leaner and more efficient processes. Accordingly, attributes associated with SDOs include for example, “slow,” “consensus,” and “compromise-laden” consortia are typically associated with “speed,” “short time to market,” and “meets real market needs.”11

However, it is safe to say that this classification, including the over-simplifying associated attributes, is not particularly helpful for organizations who want to get a better idea of what the market for standards has to offer. This holds all the more as an organization’s requirements on an SSB very much depend on a combination of factors specific to this particular organization. Also, in many sectors—particularly including e-business—most SDOs have taken a back seat; the most important standards (e.g., XML, ebXML, UDDI, etc.) have been developed by consortia.

Accordingly, a more flexible approach toward classification is called for. Rather than pre-defining certain categories, a set of attributes can be used to describe SSBs. This description can then be matched onto an organization’s requirements on SSBs, thus allowing companies to identify those SSBs that best meet their specific needs. These attributes fall into four categories (for a more detailed discussion see Jakobs et al. (2005a):

• General: Governance, IPR policy, reputation, competition.

• Membership: Membership classes, active members.

• Standards setting process: Overall time frame, consensus, transparency, decision mechanisms.

• Output: Products, maintenance.

If a company is clear about its strategy in relation to e-business, applies these attributes to describe SSBs, and maps this description onto the characteristics of its strategy, an SSB’s suitability as potential platform for a new standards-setting activity should become immediately apparent.12

FUTURE TRENDS

The current environment forces companies with a business interest in the e-business sector (primarily large vendors and service providers, but also leading-edge users) to participate in a vast variety of SSBs.13 This is certainly an undesirable situation and a higher level of coordination between consortia and between consortia and SDOs would be highly desir-able.14 The latter could be achieved through an adequately flexible and speedy transposition process from consortia specifications to formal standards. In addition, a division of labour might be helpful, whereby long-lived “infrastructural” technologies could be dealt with by the SDOs through their “traditional” process, and short-lived other technologies could be within the realm of consortia and the SDO’s new “lightweight” processes.15

This changing landscape will also continue to have major ramifications for European policy makers as well, many of whom still consider SDOs (especially the European standards organizations, ESOs) as superior to consortia. Unfortunately, this is not just a minor side issue—standards are referenced in procurement documents and in European directives. Accordingly, the largely unreflected categorization SDOs vs. consortia represents a severe disadvantage for the (products of) the latter.

Competition between SSBs will prevail—this holds for both consortium vs. consortium and consortium vs. SDO. Policy makers need to do something about this by encouraging both camps to improve cooperation or at least coordination. Whether or not this is going to happen anytime soon remains to be seen. For the time being, it appears that at least in Europe policy, interest is solely focussed on the ESOs.

CONCLUSION

The standardization environment in the e-business sector has been undergoing significant changes over the last couple of years. Arguably the most important development has been the proliferation of standards consortia, largely created out of frustration about the “formal” standards setting process, and typically driven by a group of major industry players. At least in the early days of this development, consortia were widely considered as being more efficient than SDOs, and more oriented toward the needs of the industry. The time-to-market of their standards, and of the products based on them, were also said to be vastly superior to those of SDOs. These standards did not have to go through an often time consuming broad consensus process. Moreover, consortias’ working groups were thought to be far less influenced by politics and/or private agendas, as everyone was supposedly working toward an agreed common goal.

It seems, however, that this initial enthusiasm has somewhat faded over time. Ironically, one reason for this was the increasing importance of consortia. In many areas, their specifications have become way more important than those of the SDOs. For example, for quite a while the W3C almost held a monopoly on standards for the World Wide Web (this has changed with the advent of new consortia covering similar ground). Accordingly, the stakes increased, consensus became much harder to achieve, and as a result, the time to marker for consortium standards increased.

Also, faced with the new competition, the established SDOs fought back, new deliverables being their major weapon here. That is, in order to better compete with consortia and in what must be considered an attempt to mimic the rules and processes of the major consortia, most SDOs introduced lightweight processes, leading to specifications with a lower level of consensus. These specifications do not go through the full consensus forming process as the formal norms do, and are thus more akin to the deliverables of the consortia. Typical examples here include ISO’s technical reports, ETSI’s technical specifications, and the CEN/ISSS workshop agreements. On the other hand, the processes of some of the major consortia (notably OASIS and W3C) can hardly be distinguished any more from those of the SDOs. In consequence, we can observe a convergence of the two formerly separated standards worlds. This is not to say that competition has stopped, but it is becoming increasingly hard to distinguish consortia and SDOs based on their processes and output.

This and other aspects need to be taken into account by those who wish to actively contribute to standards setting. To this end, a method has been outlined to describe SSBs in such a way that their respective suitability as potential platforms for a standards-setting activity may be derived from it. That is, this method can be applied by a potential standards-setter to identify the SSB that will be most suitable for its current needs.

Obviously, the result of this exercise will heavily depend on the strategic goals of the company. The described classification scheme for standards users takes into account the overall goals of a company, its business model, and its strategies with respect to the industry sector in question. Taken together, these may require to

• strategically influence the market through standardization,

• exert tactical influence on (the technical details of) a standard, and

• observe.

The interpretation of the description of an SSB heavily depends on these goals. For instance, for a company aiming to influence the market through a new standard—without any specific interest in its technical nuts and bolts—a group of influential key players (i.e., leaders) who would also support this standard is essential. On the other hand, for a company wishing to influence the technical content of a standard it will be more important not to have any strong potential opponents. It will also favor more egalitarian memberships.

Thus, in order to optimize its standardization activities a company needs to know its own goals, identify the key players in the sector in question, and apply the described method. This should at least lead to a reasonably good initial idea of which SSB to select for a new standards setting activity.

KEY TERMS

Electronic Business/E-Business: Business processes empowered by information systems, utilising electronic communication media (e.g., the Internet).

Interoperability: The ability of two or more systems to exchange information and to use the information that has been exchanged.

Standard: A document established by consensus and approved by a recognized body that provides, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines, or characteristics for activities or their results, aimed at the achievement of the optimum degree of order in a given context.

Standardization: The process of setting standards.

Standards Consortium: A coalition of organizations formed with the intent of setting standards in a certain technical domain.

Standards Developing Organization (SDO): A recognised body with a formal mandate to set standards (e.g., ISO, ITU).

Standards Setting Body (SSB): An entity that is setting standards—either an SDO or an industry consortium.