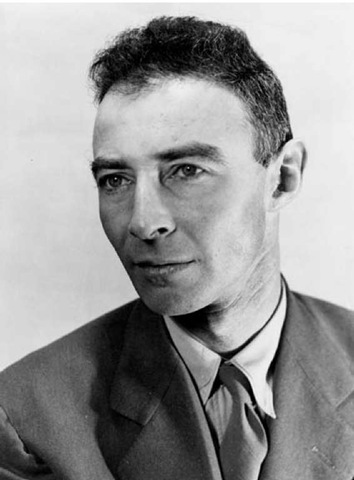

(1904-1967) American Theoretical Physicist, Quantum Theorist, Atomic Physicist, Nuclear Physicist

J. Robert Oppenheimer was a brilliant theoretical physicist who made important contributions to quantum mechanics and nurtured the development of an outstanding theoretical physics community at the University of California, Berkeley. His name is forever associated with the development of the first atomic bomb in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where he was director of the Manhattan Project, and, in particular, with the moral and ethical controversies faced by physicists who participated in the creation of weapons of mass destruction.

He was born in New York City on April 22, 1904, the elder of Ella and Julius Oppenheimer’s two sons. His father was a German Jew who immigrated to the United States at the age of 17 and made a fortune importing textiles. Robert was a frail, studious child, who would later describe himself as an “unctuous, repulsively good little boy,” whose schooling failed to prepare him for life’s cruelties. He attended the Ethical Culture School in New York, which was founded on the principle “Man must assume responsibility for the direction of his life and destiny.” His interest in science was sparked by his grandfather’s gift of a mineral collection. At age 12, the precocious child gave a lecture at the New York Mineralogical Club.

Oppenheimer entered Harvard University in 1922 and graduated summa cum laude in only three years. He would later describe his undergraduate years as the most exciting of his life, when he “intellectually looted the college,” usually taking six courses and auditing four. He had a talent for languages, excelling in Latin, Greek, French, and German. He published poetry and studied Eastern philosophies—subjects he would pursue all his life. While majoring in chemistry, he was quickly drawn to understanding the physics that underlay the chemistry and began working in the laboratory of the future physics Nobel laureate percy williams bridgman.

On the strength of a letter from Bridgman, who did not conceal the fact that Oppenheimer’s strengths were analytical, not experimental, he was accepted by the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge. He sailed to England in 1925, an exhilarating time for a young physicist to be in Europe. Postwar work on quantum theory was just getting under way, and Oppen-heimer’s work at the laboratory, which, under the direction of ernest rutherford, was internationally renowned for its pioneering studies on atomic physics, exposed him to the latest ideas. His acquaintance with niels henrik david bohr, the guiding spirit of quantum mechanics, was the turning point in his decision to commit himself to theoretical physics.

J. Robert Oppenheimer made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His name is forever associated with the development of the first atomic bomb in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Oppenheimer had already published two papers on quantum mechanics when he accepted max born’s invitation to study in Gottingen, Germany, in 1926. He earned his Ph.D. there in 1927 with the dissertation “On the Quantum Theory of Continuous Spectra,” which was published in the prestigious German journal Zeitschrift fur Physik. The professor in charge of his oral examination is said to have expressed relief when the ordeal was over, fearing that the probing Oppenheimer was about to question him. Between 1926 and 1929, the young physicist published 16 papers. Together with Born he developed the quantum theory of molecules. When he returned to the United States, at age 25, he enjoyed an international reputation.

Awarded a National Research Fellowship, he headed back to Europe, honing his mathematical skills with Paul Ehrenfest in Leiden and his analytical edge with wolfgang pauli in Zurich. In 1929, he was appointed assistant professor at both the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) and the University of California at Berkeley. For the next 13 years he would commute between these two campuses, inspiring a generation of physicists and transforming the face of American physics. Under his charismatic leadership, an outstanding group of researchers attacked the problems of theoretical physics with an intensity previously unknown at American universities. His most important research involved the study of the relativistic equations for the atom developed by paul adrien maurice dirac. In 1930, Oppenheimer showed that the Dirac equation predicted that a positively charged particle with the mass of an electron could exist. This particle, detected in 1932 and called the positron, was the first example of antimatter. He also did research on the energy processes of subatomic particles, including electrons, positrons, neutrons, and mesons. In addition, his analyses anticipated many later finds in astrophysics, including neutron stars and black holes.

During these California years, in the early thirties, Oppenheimer’s political consciousness was awakened by the rise of fascism in Europe. He became deeply concerned about the fate of Jews in Germany, where he had relatives, many of whom he would later help to escape. He formed friendships with Spanish students who were Communists and in 1936 he sided with the republic during the Spanish Civil War. He would stop short of joining the Communist Party, however, finding he could make “no sense” of its dogma.

In 1939 Oppenheimer met his future wife, Katherine Puening, known as Kitty, who would bear him a son and a daughter. Also in that year Bohr, who had escaped from Denmark to England, brought word that the Germans had split the atom. albert einstein and Leo Szilard wrote their famous letter warning President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that the Nazis could be the first to make a nuclear bomb. When Roosevelt established the Manhattan Project in 1942, giving the United States Army responsibility for the joint efforts of British and U.S. physicists to develop an atomic bomb, Oppen-heimer became its director. In 1943, he set up a new research station at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where he assembled a team of first-rate scientific minds, including hans albrecht bethe, enrico fermi, and edward teller. The quality of Oppenheimer’s supervision of the more than 3,000 people working at Los Alamos is generally believed to have been a crucial factor in the project’s success. According to Teller, Oppenheimer was probably the best lab director I have ever seen, because of the great mobility of his mind, because of his successful effort to know about practically everything important invented in the laboratory, and also because of his unusual psychological insight.

On July 16, 1945, Oppenheimer was present at “Trinity,” the first test of an atomic bomb, in the New Mexico desert. He described his initial reaction with masterful understatement: “We knew the world would not be the same.” With three other scientists who had been consulted on how to deploy the bomb, Oppenheimer recommended that a populated “military target” be selected. Within a month, two bombs were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, leading to the Japanese surrender on August 10, 1945. Oppenheimer would later write:

I have no remorse about the making of the bomb and Trinity. That was done right. As for how we used it… I do not have the feeling that it was done right. . . . Our government should have acted with more foresight and clarity in telling the world and Japan what the bomb meant.

After the war, as chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Oppenheimer continued to experience the limits of his influence over the technology he had played so central a role in developing. Along with most members of the commission, he opposed the creation of a hydrogen bomb. But when the Soviets exploded a nuclear device in the summer of 1949, President Truman gave the H-bomb project a green light. Although Oppenheimer’s offer to resign was not accepted, his opposition to the hydrogen bomb was to have dramatic consequences. In 1953, in the heat of the McCarthy era, when anti-Communist hysteria reigned, Oppenheimer was accused of having Communist sympathies. The Federation of American Scientists rushed to his defense, to no avail. President Eisenhower ordered he be stripped of his security clearance, and Oppenheimer’s influence on national science policy came to an end.

In the eyes of the world, Oppenheimer has come to epitomize the plight of the scientist, attempting to assume moral responsibility for the consequences of his discoveries, who becomes the target of a witch-hunt. Yet there is a darker side to Oppenheimer’s struggle; four years earlier, in 1949, perhaps wishing to shore up his own position, he had joined forces with the witchhunters, denouncing several of his colleagues as Communist sympathizers before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In his last years, as director of the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton, Oppenheimer devoted much of his time to writing about the problems of intellectual ethics and morality. In 1963, President Johnson awarded him the Enrico Fermi Prize, the highest award the AEC confers, as an attempt to make amends for his unjust treatment. In 1966, he retired from Princeton, where he died on February 18 of the following year, of throat cancer. His final printed words were “Science is not everything, but science is very beautiful.”