(1905-1991) American Experimentalist, Particle Physicist

Carl David Anderson built an enhanced cloud chamber with which he discovered the positive electron or positron, an achievement that garnered him the 1936 Nobel Prize in physics, as well as the positive and negative muon (or mu meson).

He was born in New York City on September 3, 1905, the son of Swedish immigrants, and attended the California Institute of Technology, where he received a B.Sc. in physics and engineering in 1927. He was awarded a Ph.D. in 1930 for a dissertation on the space distribution of photoelectrons emitted from various gases as a result of irradiation with X rays. Although his nominal dissertation director was robert mil-likan, who had accurately determined the charge of the electron, Anderson complained, “Not once in the three years of my graduate thesis work did he visit my laboratory or discuss the work with me.”

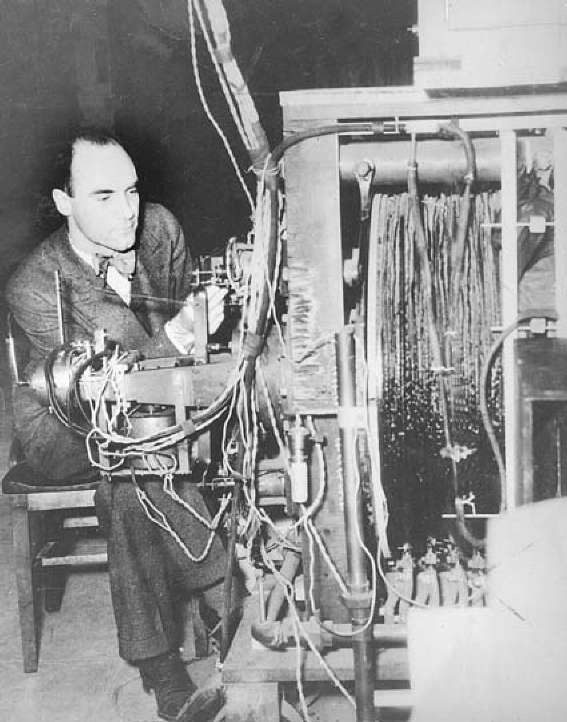

Anderson would remain at Caltech for the rest of his career. In 1930 he became a research fellow working with Millikan’s research team and began to study gamma rays and cosmic rays. Anderson built and ran the Caltech Magnet Cloud Chamber: a special type of cloud chamber that was divided by a lead plate in order to slow the particles sufficiently for their paths to be accurately determined. He used it to measure the energies of cosmic and gamma rays, by measuring the curvature of their paths, in strong magnetic fields (up to about 24,000 gauss or 2.4 tesla). In 1932, he announced that he had obtained “dramatic and completely unexpected” results: approximately equal numbers of positively and negatively charged particles, where only electrons had been expected. He also noted that in many cases several negative and positive particles were simultaneously projected from the same center. At first he assumed that the positive particles were protons; however, it turned out that their mass was identical to that of electrons (as opposed to the much heavier protons), and so he called them positive electrons. He went on to suggest the name positrons for these antimatter particles. The previous year paul adrien maurice dirac, on the basis of his rel-ativistic theory of the atom, had predicted the existence of a positive electron when he discovered that the mathematical description of the electron contained twice as many states as were expected. Working with his first graduate student, Seth Neddermeyer, Anderson also showed that positrons can be produced by irradiation of various materials with gamma rays. In 1932 and 1933, lord stuart blackett, sir james chadwick, and the Joliot-Curies independently confirmed the existence of the positron and later elucidated some of its properties.

In 1933, Anderson was promoted to assistant professor of physics at Caltech. Three years later, when he shared the 1936 Nobel Prize with Victor Hess, the discoverer of cosmic rays, he was the youngest physicist ever to be so honored.

That same year he contributed to the discovery of another elementary particle, the muon. He and Neddermeyer transported their magnet cloud chamber to the summit of Pikes Peak, Colorado, in order to obtain more intense, higher-energy cosmic rays. After a summer at Pikes Peak, they analyzed their results and found that the positive and negative tracks were different from those made by electrons and protons and appeared to have been made by a particle with an intermediate mass. They proposed that the high-altitude tracks were new, unknown particles and called them mesotrons, because of their “middle” mass; the name was later shortened to meson. At first Anderson thought that this was the particle previously predicted by hideki yukawa, which was supposed to hold the nucleus together and carry the strong nuclear force. Further studies, however, showed that it did not readily interact with the nucleus and therefore could not be Yukawa’s particle. Anderson’s particle is now called the mu meson to distinguish it from the pi meson.

When World War II broke out, Anderson turned down an offer to direct development of the atomic bomb, “on purely economic grounds,” and the job went to j. robert oppenheimer. In the autobiography he would write in his 70s, he observes:

I believe my greatest contribution to the World War II effort was my inability to take part in the development of the atomic bomb. Thinking so brings me peace of mind.

Instead, he worked on the development of rocket launchers at Caltech and, in 1944, supervised the installation of the first rocket launchers on Allied planes.

After the war, in 1946, he married Lorraine Bergman, with whom he had two sons, Marshall and David. He served as full professor at Caltech until his retirement in 1976, when he became professor emeritus. He died on January 11, 1991, after a brief illness, at the age of 85.

Carl David Anderson discovered the positive electron, or positron, as well as the positive and negative muon.

Carl Anderson played a major role in the discovery of new elementary particles and pointed the way to the existence of antimatter. His discovery of the positron led to the prediction of other antiparticles, such as the antipro-ton discovered by emilio segre in 1955. Today the existence of antimatter—an antiparticle for all particles—is universally accepted.