Routes of Injection

Hypothetically, the best means to get a drug directly into a target organ is to inject the organ directly. Intrathecal (within the spinal column), intrapleural (between the lung’s pleura), intra-articular (within a joint), and intracardiac (within the heart) injections are just some examples of medication injections into target organs.

With the exception of intracardiac injections performed by early Paramedics before the advent of current intravenous techniques, Paramedics generally have injected drugs into the peripheral circulation and depended on the circulatory system to get the medication to the target organ. Even drugs injected into the endotracheal tube depend on absorption from the alveolar capillary beds.

The greatest drawback of indirect parenteral injection may be its dependence on adequate circulation to reach the target organ. In many cases, the patient presents to the Paramedic with inadequate circulation (these patients are hypoperfused). Subsequently, insufficient quantities of drug get to the target organs when injected via an indirect parenteral route.

Preparation for Parenteral Injection

As in all procedures performed, the Paramedic would identify the patient, introduce oneself, inquire about the patient’s allergies, advise the patient about the procedure’s intended effects, and then explain what reasonable and foreseeable risks could be experienced.

After obtaining informed consent, the Paramedic should practice medical asepsis, starting with hand washing with soap and water or an acceptable hand sanitizer and then don gloves. Generally, non-sterile gloves are adequate for the tasks at hand.

Success in many of these injection techniques can be improved if the Paramedic takes the time to first position the patient. With the patient resting comfortably, the Paramedic would proceed by selecting a site, chosen in accordance with commonly accepted sites used for that particular injection technique. When assessing the various sites for injection, before choosing one, care should be taken to ensure that the selected site is not hard, swollen, or tender and is free of rashes, moles, birthmarks, burns, scars, or broken skin.

After identifying the intended injection site, the Paramedic would place an isopropyl-soaked pad on the site and, working outward in ever-expanding circles, prepare an area approximately twice the length of the needle. The purpose of the alcohol bath is to remove any gross contaminates from the skin’s surface as well as oils that would prevent the bandage from adhering to the skin. The alcohol bath itself does not render the skin sterile, just clean. Incidental surface contamination (bacteria and the like), which may be dragged into the wound created by the injection is dealt with by the body’s defenses.

Iodine-based solutions, such as Betadine®, are generally not used because iodine seeping into the stab wound created by the injection can be irritating. It may also delay new cell growth and damage sensitive tissues in the vicinity of the injection.

With the patient prepared and the area prepped, the Paramedic would then pick up the prefilled syringe in the dominant hand and remove the needle guard. The Paramedic must then stabilize the skin with the nondominant hand. With the needle and syringe firmly in hand, the Paramedic would then proceed to firmly, and with authority, insert the needle under the skin. Studies have shown that the speed of insertion does not decrease the pain which the patient may experience.45 However, hesitation on the Paramedic’s part is telegraphed to the patient, which may cause the patient’s anxiety may increase. Patient anxiety has been shown to have a positive correlation to the perception of pain.

With the needle in place, the Paramedic would gently aspirate to ensure that the needle was not inadvertently placed into a vein. If a blood flash is witnessed, then the needle should immediately be withdrawn, the medication pulled back into the syringe, and new equipment prepared. The bloody medication solution should not be injected. Instead, a new dose of medication should be drawn up in a new syringe.

Intradermal Injection

Paramedics perform intradermal injections under a limited set of circumstances. Intradermal injection is used when preparing an intravenous site with a local anesthetic. Intradermal injection is also used for tuberculosis testing. The objective of an intradermal injection is to place a small quantity of medicine just under the epidermis and in close proximity of the subcutaneous tissue. Because the space within the skin is very small, no more than 0.5 mL should be injected into one site.

The tools that the Paramedic needs to assemble for an intradermal injection include a 1 mL syringe and a short needle about 3/8 inch to 1/2 inch that is either 26 or 27 gauge. Sites for intradermal injection include the anterior forearm, the upper chest, and the posterior shoulders. After drawing up a small quantity of the medication (typically 0.01 to 0.1 mL), the patient is prepared as previously described.

Grasping the syringe as one would a sewing needle, the Paramedic would place the needle gently on the surface of the skin, with the needle at a 15-degree angle, and advance the needle under the skin. With the length of the needle under the skin, a small 1 cm blister is created by injecting the medication. This blister, called a bleb, is about the size of a mosquito bite. The needle should remain visible just under the skin the entire time.

When the task is completed, the needle is withdrawn in the same direction as it was advanced and immediately placed in a sharps container. If capillary bleeding is evident, then an adhesive bandage can be placed loosely over the site.

Capillary Blood Draw

Paramedics are increasingly requested to perform capillary blood sampling in the field. The capillary blood can then be used for blood glucose analysis or field Troponin levels. These point of care blood tests enhance the Paramedic’s ability to provide immediate emergency services while still in the field and to transmit critical information to the emergency department.

The most common capillary blood draw is the finger stick. However, a heel stick may be preferred for small infants or children. With the limb in the dependent position, encouraging peripheral vascular congestion, the Paramedic would proceed with the routine battery of questions in order to obtain consent.

Once consent is given, the side of the finger tip proximal to the pad of the finger tip is cleansed with an alcohol prep pad (wipe). While the alcohol is drying, the lancet is picked up by the dominant hand and prepared. In some cases, a protective cover must be removed from the lancet. In other cases, the lancet is spring-loaded and retracts back into a protective sheath. In those cases, the lancet may have to be activated (armed) before use.

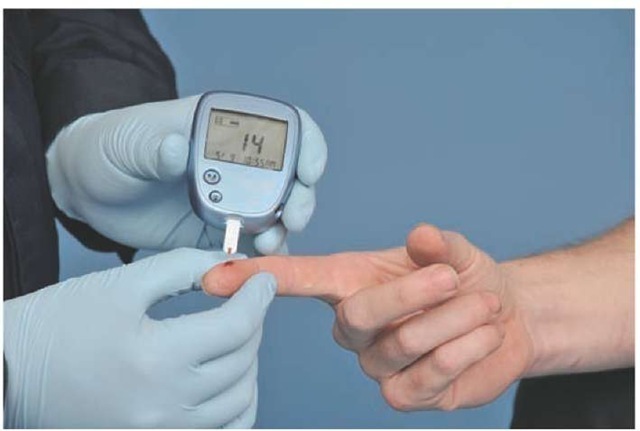

Figure 26-8 Capillary blood draw.

Grasping the patient’s finger with the gloved nondomi-nant hand, the Paramedic would place the lancet over the site and either pierce the skin in a quick darting motion or depress the actuator of the spring-loaded lancet. Once the skin is pierced, it should bleed freely. In some cases, it may be necessary to gently milk the tip of the finger to get a hanging drop of blood. Vigorous or forceful pressure on the tip of the finger may damage local tissue. It might also introduce new fluids into the sample, possibly causing any subsequent blood test results to be invalid.

After immediately disposing of the lancet in an approved sharps container, the Paramedic would collect the droplet sample and then apply a gauze pad or self-adhesive bandage to the fingertip. The patient should be encouraged to elevate the arm above the heart (Figure 26-8).

Subcutaneous Injections

Subcutaneous injection of medication is the slowest and least dependable means of obtaining therapeutic drug levels in the bloodstream. Local conditions in the skin, such as capillary perfusion and adipose tissue, combine to make drug absorption slower and more erratic than intravenous injection.46-48 Yet for some medications, such as heparin and insulin, the subcutaneous route is acceptable.

After providing the appropriate information and obtaining consent, an acceptable site is prepared. A variety of sites are acceptable for subcutaneous injections including the abdomen, the lateral aspects of the upper arm, and the anterior thigh, as well as the ventrodorsal gluteal area. Studies have shown that the subcutaneously injected medication is absorbed quickest from the abdomen, followed by the upper arm and then the anterior thigh. There is no data comparing the gluteal injections to the other sites.

A complication of frequent subcutaneous injections at one site, such as may occur with repeated insulin injections, is tissue fibrosis. Tissue fibrosis occurs when phagocytes infiltrate the area and attempt to remove the irritating foreign matter (the medication) and create a sterile abscess. Drugs injected into fibrotic tissues cannot be absorbed readily and will adversely affect the patient’s response to the medication.

Generally, a 1 mL to 3 mL syringe is used for subcutaneous injections. The syringe is tipped with a 1/2-inch 26 to 30 gauge needle. With the syringe loaded with no more than 1.5 mL of medication for one injection and held in the dominant hand, the Paramedic would gently grasp the skin around the site with the nondominant hand. With the skin tented approximately 1 inch between the fingers, the Paramedic would insert the needle into the skin at a 45-degree angle. If the skin is tented approximately 2 inches, then it is acceptable to insert the needle at a 90-degree angle. Once the needle is inserted into the skin, the Paramedic would gently aspirate for blood and then inject into the subcutaneous pocket which has been created by pinching the skin.

Intramuscular Injections

Intramuscular injection is a common method of medication administration. Once the drug is deposited between the layers of the muscle, and below the subcutaneous tissue, it can escape into the surrounding capillary beds within the muscles and provide rapid systemic action. Intramuscular injection is frequently used for the uncooperative patient who is in need of sedation/chemical restraint to prevent harm to himself or others. Antipsychotic agents, such as haloperidol, can be given in this manner during a psychiatric or behavioral emergency. However, not all medications should, or can, be given via intramuscular injection. Digoxin, diazepam, and pheny-toin are just some of the medications that are poorly absorbed via intramuscular injection.

Intramuscular injection has an advantage over intravenous injection in the elderly and immunocompromised patient. Intravenous injection bypasses the majority of the body’s defenses against infection, whereas intramuscular injection preserves several of those defenses.

Intramuscular injections depend on adequate peripheral circulation. Intramuscular injections, and intramuscular injections in certain sites, may be contraindicated in patients with peripheral vascular disease and disease states which create Hypoperfusion (e.g., anaphylactic shock). Intramuscular injections also create trauma during the injection, creating a puncture wound. Some patients with coagulation disorders, such as the patient with hemophilia or one who is status-post fibrinolysis, may experience significant bleeding (a hematoma) at the injection site.

The slow distribution of intramuscular medications makes intramuscular injection a preferred route for so-called depot medications. Depot medications are medications deposited under the skin which produce sustained therapeutic levels over a longer period of time.

The intramuscular needle range is between 18 to 24 gauge and the selection of the length of the needle is more important than the gauge. If the patient is less than 110 pounds (50 kg), a 1-inch needle will generally reach the muscle below the skin. If the patient weighs between 110 and 220 pounds (50 to 100 kg), then a /- to 2-inch needle is appropriate. For patients over 220 pounds, a needle longer than 2 inches may be needed. In the case of the morbidly obese patient, it may be necessary to use a 4-inch needle.49 It is important that the Paramedic carefully assess the injection site. Variations in muscle development can alter the Paramedic’s decision regarding needle length.

Because of the barrel’s diameter, a 3 mL syringe is generally used for intramuscular injections as it provides better control. However, the syringe chosen is dependent on the volume to be administered per injection which is, in turn, dependent upon the site selected.

After the patient has consented and is properly prepared, the site is selected. There are four common intramuscular injection sites to choose from, and each site has specific advantages over the other sites.

The first site, the ventrogluteal (VG), is located on the lateral thigh proximal to the hip.50-52 The muscles underlying the VG are the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus. What may be more important is that no large veins, arteries, or nerves underlie the area. Beyea and Nicoll reported that the ventrogluteal site had the lowest risk of nerve damage, muscle spasm, gangrene, and pain of any of the other injection sites.

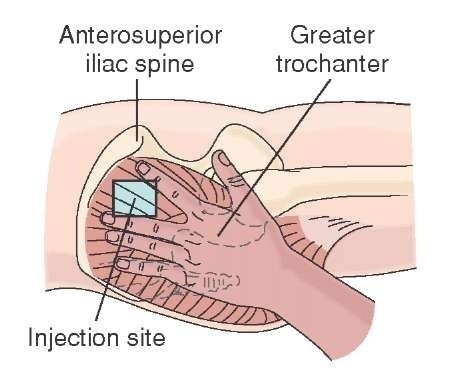

To locate the site, the patient is placed in a side-lying position (lateral recumbent). The Paramedic would then palpate the bony prominence where the femur inserts into the pelvis. Placing the palm of the hand over the insertion, the Paramedic would grasp the anterior superior iliac crest with the fingers. The injection site is between the first finger and the thumb (Figure 26-9).

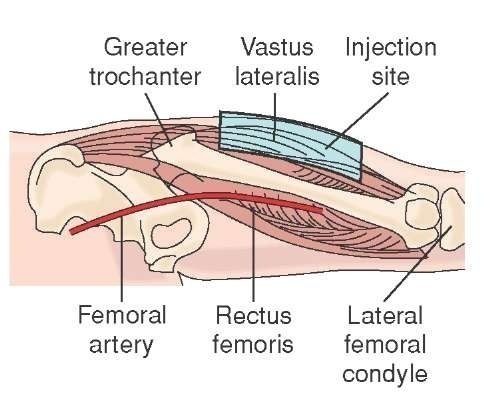

An alternative intramuscular injection site is the vastus lateralis (VL) (Figure 26-10). After positioning the patient in the supine or semi-Fowler’s position, the anterior thigh is exposed. The Paramedic mentally divides the vastus lateralis muscle into three equal portions. Choosing the middle section of the VL, the Paramedic prepares the intended injection site with an alcohol-soaked pad. Next, the Paramedic draws up the medication in the syringe and prepares the patient for the injection. Up to 2 mL of medication can be injected in the vastus lateralis without causing the patient significant discomfort.

Figure 26-9 Ventrogluteal injection site.

Figure 26-10 Vastus lateralis injection site.

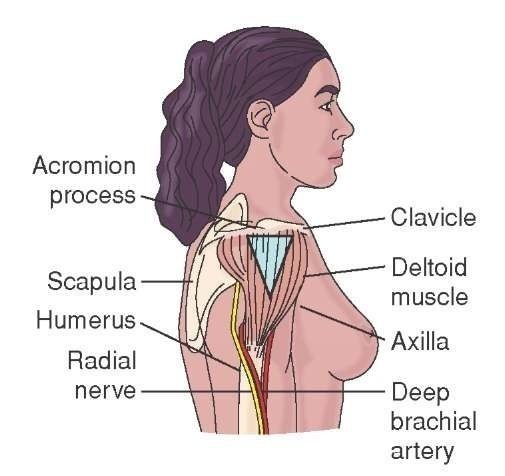

Figure 26-11 Deltoid injection site.

Paramedics generally prefer to use the deltoid muscle (Figure 26-11) because it requires less patient exposure and is easier to access. The deltoid muscle overlays the shoulder and extends downward toward the elbow, forming an inverted triangle in the process. With the patient in high-Fowler’s position, the Paramedic would instruct the patient to bend the arm at the elbow, thus relaxing the deltoid muscle. The Paramedic would then palpate the bony prominence where the humerus inserts into the shoulder. Locating the humerus, the Paramedic would measure approximately three finger-breadths down to the middle, or belly, of the deltoid muscle and prepare the site with an alcohol-soaked pad. Approximately 1 mL of medication can be given into each deltoid. The deltoid site should not be used for children who lack the muscle development in the shoulders appropriate for the injection.

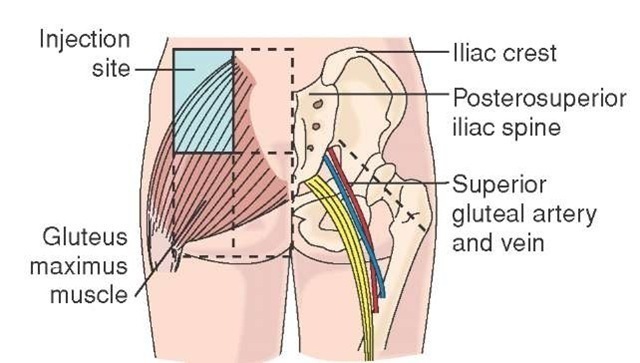

The most common intramuscular injection site is the dor-sogluteal (DG) (Figure 26-12). A large muscle, the gluteus medius, underlies the injection site and provides an excellent location for a depot of medicine. The patient is typically in the prone position (an uncommon position for patients to be transported by EMS) and then the patient’s buttocks exposed. Alternatively, the patient can be placed in the side-lying position, or lateral recumbent position, and only the upper portion of the buttocks and the patient’s flank is exposed. It should be noted that the gluteus is not synonymous with the buttock. The gluteus is located proximal to the inferior portion of the patient’s flank.

Figure 26-12 Dorsogluteal injection site.

As the gluteus medius is relatively large, compared to the muscles underlying the other injection sites, use of the DG site is advantageous during a restraint situation. In those situations where the patient needs sedation and/or chemical restraint for a behavioral emergency, the DG offers a large "target" and thus a greater chance of success. After the patient has been given sedatives, he should be placed in the supine, face-up position as soon as possible in order to monitor respirations and avoid positional asphyxia.

To ascertain the location of the DG injection site, the entire one buttock is mentally divided into four quadrants. The uppermost and outermost quadrant, proximate to the iliac crest, is prepared. Great care should be taken estimating the injection site as the sciatic nerve transverses two of the other three quadrants. Unintended injection into the sciatic nerve can lead to paresthesia, paralysis, and permanent nerve damage. Alternatively, the Paramedic can draw an imaginary line from the height of the iliac crest to the insertion of the femur and choose the midpoint of that line.

Generally, the DG injection site is reserved for adults. Children must be walking before a DG injection site should be considered. In the adult patient, a maximum of 5 mL can be injected into each DG site. However, the Paramedic should consider splitting the dose and doubling the sites for injection to increase patient comfort.