KEY CONCEPTS:

Upon completion of this topic, it is expected that the reader will understand these following concepts:

• The patient care report as an important medical, business, and legal document

• The patient care report as part of the quality assurance and performance-improvement program

• Different formats available for documentation that focus on a precise reflection of the events that occurred

• Special incidents, such as disasters, that require special reports

Case study:

After all the excitement of the cardiac arrest was over, the new Paramedic realized she was faced with the tedium of documentation. Her senior Paramedic partner reminded her that documentation is important. He said, "The patient care report is a medical document that helps the physician determine the cause of the cardiac arrest. The patient care report is also used as a quality improvement tool, allowing our supervisor to ascertain whether we met certain performance goals, to identify weaknesses in our performance and to help establish training goals to correct those weaknesses. And," as he continued, "the patient care report is a legal record." Nodding acknowledgment she opened up the laptop and started to fill the fields.

OVERVIEW

Documentation—whether it consists of patient care reports, special incident reports, affidavits, or triage tags—is an important responsibility for Paramedics. One study suggested that Paramedics spend as much as 28% of their patient contact time writing the patient care report (PCR), underscoring its importance.1

Some Paramedics, in order to focus on patient care, facilitate their report-writing by taking notes on 3 x 5 cards or notepads and then transcribe their notes to a more formal PCR later. It is also common to see a Paramedic writing critical patient information on a piece of tape affixed to a pant leg or on the corner of a sheet.

Purpose of EMS Documentation

Patient care documentation is a record of the pertinent findings and observations of the patient’s health obtained through examination. It is also a log of the tests and treatments performed.

There are six-fold reasons for Paramedics to write an accurate patient care report. First and foremost, the PCR is a part of the patient’s present medical care. Based upon the outcomes of treatments, noted on the PCR, the emergency department can make further treatment decisions. The PCR is a communication tool between the Paramedic, who has left the patient, and the emergency physician at the hospital still treating the patient. The PCR is therefore essential to the continuity of patient care. It emphasizes the Paramedic’s role as a part of the healthcare team as well.

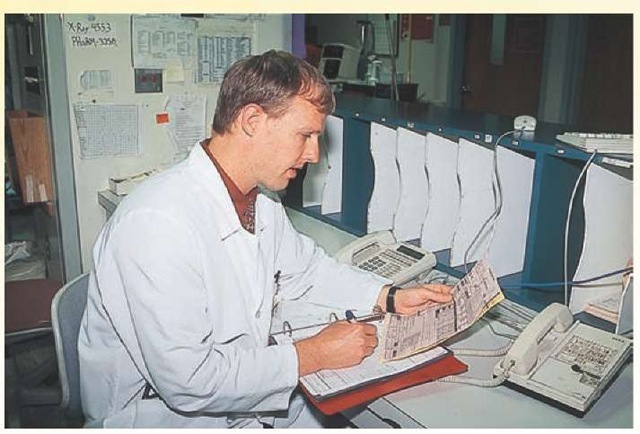

Second, the PCR is also a part of the medical record, which will be used in the future by other physicians and allied healthcare professionals for patient care. As a part of the medical record, the PCR often provides vital information to physicians about the origin of a condition or disease (Figure 19-1).

For example, a PCR written about a low-priority patient contact during a hazardous materials spill may be the evidence that links a minor exposure to a toxin to liver cancer 20 years later.

Third, the PCR is a tool for quality assurance and performance improvement programs. Through PCR audits—a careful review of the documentation for specific data— healthcare managers, EMS administrators, and EMS physicians can assure that the patient care provided out-of-hospital meets the established standard of care. PCR audits help to ensure that acceptable patient care is provided to all patients equally.

Analysis of the results of these PCR audits also helps to identify trends, such as increased patient contacts in a certain segment of a city or a consistent problem with patient care in a specific patient population. Identification of system issues in this manner provides EMS managers with an opportunity to remodel the system or educate the Paramedics.

Figure 19-1 Physicians use prehospital patient care records to obtain information that might otherwise be unavailable.

Fourth, the PCR is a business record used for billing and operations. Careful and accurate documentation helps to ensure that insurance claims reviewers, during utilization review, will accept the patient care charges submitted.

Fifth, EMS researchers may also use the PCR as a research document. Following changes in EMS care documented on the PCR, researchers can publish either descriptive research findings or, using an experimental design, investigate new treatments in the field.

EMS educators often use selected PCRs for case presentation in a case of the utility of a practice. EMS physicians, in the course of a medical audit, often select illustrative cases documented on a PCR for individual instruction or an agency’s continuing education. The PCR can also be utilized in a case-based method of teaching. These PCRs are often illustrative of a unique solution to an unusual problem or as a reinforcement to established methods.

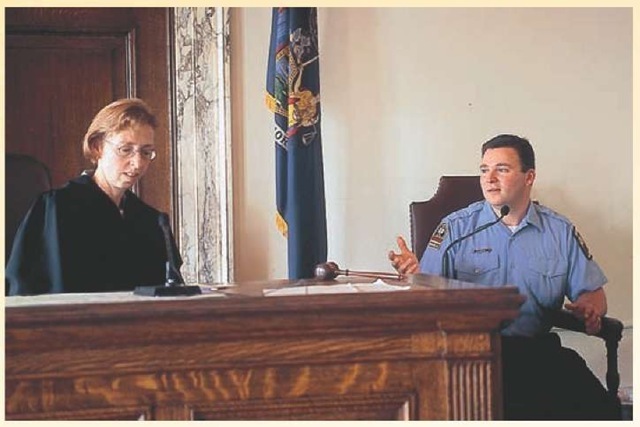

Finally, the PCR is a legal record. The Paramedic can be subpoenaed to court with the PCR to testify during a trial (Figure 19-2). The PCR can be used as evidence in a trial. The trial may or may not even involve EMS as an issue. That PCR, exhibited to others in the legal system and the public, reflects upon its author and all other Paramedics.2

Figure 19-2 The prehospital patient care report is a legal document as well as a medical record.

A PCR is an important tool for a Paramedic during a trial. With the number of lawsuits against Paramedics rising, Paramedics will depend on the PCR as a source of information to aid recall for activities on an EMS scene which may have occurred five or six years previously.3

Elements of a PCR

A PCR has many fields, which are places to enter data. Most of the fields are for patient care information, although some fields on a PCR are for administrative and/or business information.

In the past, documentation of patient care was imprecise and simply noted. For example, documentation may have stated that a person was transported and indicate very little else.

Physicians have entrusted a great deal of responsibility to Paramedics. However, physicians need to know how the patient was treated in the field. This reveals the need for thorough documentation. In addition, administrators (both public and private) who have interested "stakeholders," as well as the legal system, have mandated more thorough documentation of patient care.

Documentation Standards

At a minimum, a Paramedic should document the reason for the urgent transportation of a patient to an emergency department. The federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMMS), in its definition of an emergency, states that an EMS call is medically necessary when the patient experiences a sudden onset of acute symptoms for which emergency medical intervention at a hospital would seem necessary. Medical necessity further requires that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably result in jeopardy to health, serious impairment of bodily function, or a serious dysfunction of a body organ or part.

The last statement is somewhat problematic as it assumes a foreknowledge of a determination yet to be made. Appreciating that the patient lacks this knowledge, and that the patient calls for EMS because of a belief that it is an emergency, the federal government has accepted the prudent layperson standard. The prudent layperson standard means that another person, not a physician, who was in the same or similar circumstances would think it is appropriate to call EMS; this is paraphrased from larger state and federal definitions.4,5

However, simply stating that there is a medical emergency, using the previous standard, is insufficient information for the purposes of the medical record, utilization review, and the courts. To fulfill the needs of these other parties, the Paramedic needs to provide complete documentation of care from the arrival on-scene to the transfer of care at the hospital.

Following a proscribed format the Paramedic should legibly write down his or her observations on the patient care record in black ink. If an action or observation is not documented, then that information is lost. While the loss of vital information can potentially harm the patient, it also calls into question the thoroughness of the Paramedic’s exam and the justifications for treatment. The saying "If it wasn’t written down, then it didn’t happen," suggests that a treatment performed by the Paramedic is considered never to have happened, despite a Paramedic’s protestations, if it wasn’t recorded. As a result, there may be an appearance of dereliction of duty or possible negligence on the Paramedic’s part.

STREET SMART

The use of black ink for documentation permits a clear copy when the PCR is faxed, photocopied, microfiched, or scanned into a document reader. For this reason, many agencies only permit black ink to be used.

Legibility is another important issue in documentation. The purpose of the PCR is to transfer the information to, or communicate with, the physician and other patient care providers. If the writing is indecipherable, then the function of the document is lost. It is a good practice to have another Paramedic, one who was on-scene, read the PCR. Such proofreading serves several purposes. It helps to establish consensus regarding the observations and actions of the team, as well as ensures the readability of the PCR.

The use of slang and jargon in a PCR is inappropriate and unprofessional. Such terms do not add to the patient record and unnecessarily serve to distract the reader from the message. Similarly, bias and prejudice have no place on a PCR.

As a rule, Paramedics practice conservation with words and avoid excessive wordiness. While reading such technical writing may seem dry, its intention is to be precise and to convey a maximum amount of information in a short period of time.

Errors and Omissions

When an error is made on the PCR, the Paramedic should "strike-out" the mistake with a single line, leaving the content below the strike-out legible. Next to the strike-out, the Paramedic should place the date and initial the strike-out to indicate authorship. Heavy cross-outs give an appearance of deception, as does the use of erasure polishes such as White-out®, leaving the Paramedic open to questions about integrity.

It is common practice to place a single diagonal line across any open areas of the document, called "line-out," in order to prevent the addition of new content to a PCR by others after the Paramedic has completed the PCR.

Upon completion of the document, some Paramedics sign-out with time, date, and initial after the last entry. The line-out and the sign-out indicate that the PCR was written and completed by the person listed "in-charge" at the time and date listed.

Upon re-reading the PCR and determining an entire passage or entry is substantially in error, the passage should not be removed but instead "crossed out" with a single slash that is then dated and initialed. A revision should then be written on another page or on a continuation form with cross-reference made to the first entry (e.g., see PCR 123).

It is also permissible to add to the record after the call. In that instance, another page should be added. Additions should only be added when the entry will substantially clarify the record or document important patient information useful to the physician.

As a rule, there should be only one author for each PCR. Multiple authors generate concerns about the authenticity of the document and the accuracy of the events depicted. Discussion and collaboration with fellow EMS providers during the creation of the PCR should eliminate the need for multiple authors (Table 19-1).

Confidentiality

Some Paramedics use a facsimile machine to transmit documentation (e.g., to send the PCR from a base station to the hospital). The use of a facsimile machine (FAX) may be acceptable provided a few safeguards are in place.

Table 19-1 Documentation Standards

|

• |

Black ink is preferred. |

|

• |

Legibility is important. |

|

• |

Slang and jargon is not used. |

|

• |

Errors noted with single strike-through and initialed. |

|

• |

Empty space is lined out. |

|

• |

Sign-out includes initials, date, and time. |

|

• |

One author for each record. |

The central question with facsimiles is confidentiality (i.e., did the PCR get to the intended recipient?). When "faxing" a PCR, the Paramedic should contact the receiver and advise that a facsimile will be transmitted shortly. When the facsimile is received, the recipient should respond with a verification of receipt.

If the PCR is inappropriately sent to the wrong address, the cover sheet should clearly indicate that the facsimile is confidential and ask the recipient to destroy the copy. If the Paramedic knows that the transmission was made in error, then the Paramedic should call the other party and request that the unintended recipient destroy the PCR.

Current regulations under the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) may make the use of a facsimile machine inadvisable in the future (Figure 19-3). Also, such practices should be carefully scrutinized for compliance with regulations regarding confidentiality.6

Forms of Documentation Electronic Documentation

Electronic documentation, although still in its infancy, is rapidly becoming state of the art. The use of mobile data terminals (MDT) on-board the ambulance or personal digital assistants (PDA) have replaced the pad and paper.

Electronic documents have several advantages over traditional documentation. Computers have built-in spell checker and grammar checker programs, increasing the readability of the PCR. Electronic documents can also have forced fields, mandatory fields which must be completed before submission. The use of forced fields helps to ensure that a minimum data set is completed. Data sets are discussed shortly.

Concerns about limited data entry has plagued electronic documentation programs in the past, but the addition of dropdown menus and handwriting recognition programs have helped eliminate some of those concerns.

To ensure patient confidentiality, all electronic documentation programs should be password protected and the password changed as frequently as every 30 days. To further safeguard patient confidentiality, Paramedics should routinely shut down documentation programs when not in use to prevent uninvited intruders from entering the program and altering the record.

Figure 19-3 HIPAA regulations impact recordkeeping.

On-Scene Medical Records

The combination of mobile data terminals, secure satellite uplinks, and computer databases makes the possibility of obtaining patient medical records, while on-scene, not only possible but probable. The American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM) has already produced standard F1652-95, Standard Guide for Providing Essential Data Needed in Advance for Prehospital Emergency Medical Service. The standard includes requirements for secure access and authorized use in order to protect patient confidentiality, as required under federal HIPAA regulations.

Problem-Oriented Medical Recordkeeping

In the past, physicians had private records for each patient that were stored in their offices. These were shared only with the patient and office staff whom the physician generally knew personally. Tracking the progression of a patient’s disease in some cases was largely a function of the physician’s memory.

With the advent of hospitals, medical specialties, and allied healthcare providers, all of whom need the same information, some order had to be brought to the massive collection of records generated for each patient by each provider. To help solve the dilemma, Dr. Lawrence Weed of the University of Vermont’s Medical School advocated the concept of problem-oriented medical recordkeeping (POMR) information systems in 1969 to track and manage patient records.

In a POMR system, the master problem list of the record would list the medical conditions for which that patient had been, or currently was, receiving treatment.710 Indexed as such, new entries in the medical record, called progress notes, would be placed into the patient’s file under the problem listed. All healthcare professionals, from physicians to nurses to dieticians, would place their entries into the patient’s record using the SOAP notes format.

The SOAP format may be one of the earliest standardized documentation formats. With POMR, any allied healthcare provider could open up the patient’s record, called a chart, and read what other providers were planning to do, as well as review the patient’s progress. With this knowledge in hand, the provider would make a patient assessment and then enter his or her SOAP note following the last entry.

The SOAP note would contain subjective (S) information obtained from the patient or the patient’s family, objective (O) information obtained during physical examination, an assessment (A) of the patient’s problem, and a plan (P) for action. SOAP notes proved to be invaluable for integrating information among a variety of healthcare professionals and ensuring the continuity of patient care.

EMS PCR Formats

Early EMS providers adopted the SOAP notes system for their documentation system. In some states, the progress note was virtually a blank sheet of paper, called an open form. The Paramedic was expected to document assessments and other information in SOAP format on the paper. While this approach permitted a great deal of freedom for documenting the patient’s condition in a narrative manner, almost like telling a story, it made data gathering difficult for both the physician (who had to read the entire report to find one vital piece of information) and researchers (who looked at dozens of reports for one set of information).

In response to the need for standardized data collection, minimum data sets have been established. A minimum data set requires that the Paramedic complete certain fields with the requested information. The minimum data set permits the Paramedic and physician to track trends and note patient progress. A simple example of a data set would be response times. All EMS agencies strive to meet preset maximum response times (e.g., to be on-scene, or off the floor, in 10 minutes). Some agencies are obligated by contract to be on-scene in a minimum time. In both cases, the EMS agency wants to know its response times.

Every data set must also have a definition. In the previous example, does scene arrival mean when the ambulance is at the dispatched location or at the patient’s side? The difference in these two interpretations of response times can mean minutes to a patient—minutes that make a difference in the patient’s survival, such as with cardiac arrest.

The American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM) has proposed a minimum data set for EMS, standard E1744. E1744-04 contains similar data sets as the Data Elements for Emergency Departments (DEEDS), a program distributed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1979. Inclusion of DEEDS data sets into EMS data sets helps ensure a seamless documentation of care from the prehospital environment to the emergency department.

Using standardized data sets has tremendous research potential. With integrated standardized data sets, the efficiency of prehospital interventions can be measured against hospital patient outcomes and recommendations made for future practice.

To integrate patient information with minimum data sets, many EMS systems use a closed form method of documentation. Closed form documents use bubble forms, circles next to options, which the Paramedic fills in to provide information. These bubble forms can then easily be scanned by electronic readers to quickly obtain vast quantities of information.

Closed form documents assume most patients will have the same or similar complaints, symptoms, and so on, and are very restrictive. As a result, many Paramedics complain about their inability to document unique conditions or situations.

Many EMS systems use a combined form, one that has characteristics of a closed form and an open form. These combined forms allow rapid information gathering (the minimal data set), as well as the freedom to use some narrative, if needed.

CHEATED

Good patient care records paint an accurate picture of the patient’s condition. For a time, SOAP notes were adequate. But as time progressed, Paramedics became increasingly dissatisfied with SOAP notes and started to modify the format to include elements unique to EMS.