Vertebral Column

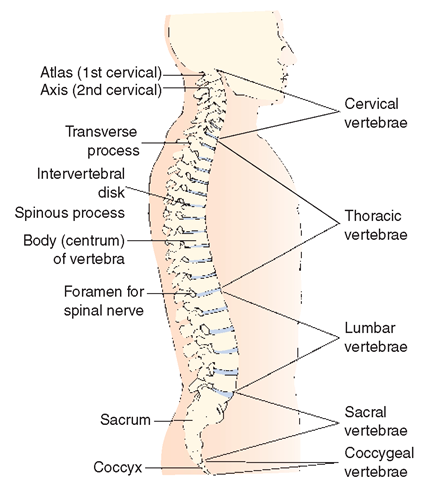

The vertebral column (spine) holds the head, allows twisting and bending, stiffens and supports the middle portion of the body and holds it upright, and provides attachments for the ribs and pelvic bones (Fig. 18-8). The spine also protects the spinal cord, which passes from the brain down through the vertebral foramina. In children, the vertebral column consists of 33 or 34 bones. Fusions of these bones occur during growth and development. Therefore, the vertebral columns of most adults consist of 26 bones, or vertebrae. The normal spine has four curves that help balance the body. Disease, injury, and poor posture distort these curves.

Special Considerations : LIFESPAN

Spine Abnormalities

Scoliosis is an abnormal lateral (sideways) curvature of the spine. It occurs most commonly during adolescence and is more frequently found in girls than boys. Lordosis, also known as "swayback,” is an exaggeration of the normal lumbar spine curve in the small of the back. Assessment during routine health examinations in children includes evaluation of the straightness of the spine or of abnormal curvatures of the spine.Kyphosis, most common in women, is commonly known as "widow’s hump” or "humpback,” and is often caused by osteoporosis.

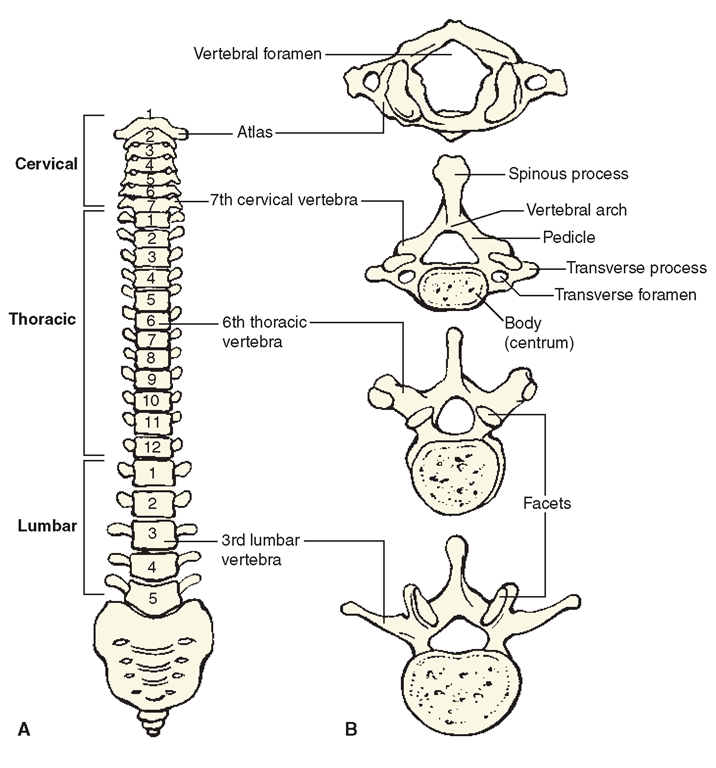

The vertebrae are shaped like rings and are constructed on a common plane; each vertebra varies in its structure, but is designed to fit the vertebra beneath it (Fig. 18-9). The top seven vertebrae (in the neck) are called cervical vertebrae. The first vertebra, the atlas, supports the skull. The second vertebra, the axis, has an especially wide surface so the head can turn freely.

Directly below the cervical vertebrae are 12 thoracic vertebrae, to which the ribs are attached. The next five vertebrae are the lumbar vertebrae. They are located in the small of the back. In adults, the sacral vertebrae are fused together (the sacrum), which anchors the pelvis. The spinal column ends in a single bone in adults, the coccyx, commonly called the tailbone.

FIGURE 18-8 ·A normal spine.

Special Considerations :CULTURE & ETHNICITY

Vertebrae

Most people have 26 vertebrae. Individuals from certain ethnic groups may have fewer—11% of African American women have 23 vertebrae, and 12% of Alaska Natives and Native Americans have 25.

Special Considerations :LIFESPAN

Sacral Vertebrae in children

Children have five sacral vertebrae. These fuse to form the sacrum in the adult. Also in children, the last four vertebrae, the coccygeal vertebrae, are small and incomplete. These vertebrae later fuse to form the coccyx in the adult.

Rounded plates of cartilage, the intervertebral disks, separate the vertebrae anteriorly from one another. They act as shock absorbers during walking, jumping, or falling. A “slipped” disk refers to an intervertebral disk that has shifted out of position. A “ruptured” disk occurs when pressure forces less dense tissue sideways, causing a protrusion in the disk walls (like a squashed grape). Either situation can place pressure on a nerve, causing great discomfort.

FIGURE 18-9 · (A) Front view of the vertebral column. (B) Vertebrae from above. Note that there is cartilage between the vertebrae, called intervertebral disks.

On the inner side of each vertebra is a bony structure called the arch, which forms the spinal (vertebral) foramen, the opening through which the spinal cord passes. Jutting from the arch are several bony processes or extensions, to which ligaments and tendons of the back muscles are anchored. The muscles, ligaments, and cartilage disks help make the vertebral column strong, yet flexible. They enable the person to comfortably bend forward, backward, and side-to-side and to rotate the central portion of the body.

The ribs articulate with the vertebrae at facet joints. These joints are lined with cartilage, but may become misaligned. Many cases of back pain, particularly in the lower back, involve misalignment of facet joints.

Thoracic (Rib) Cage

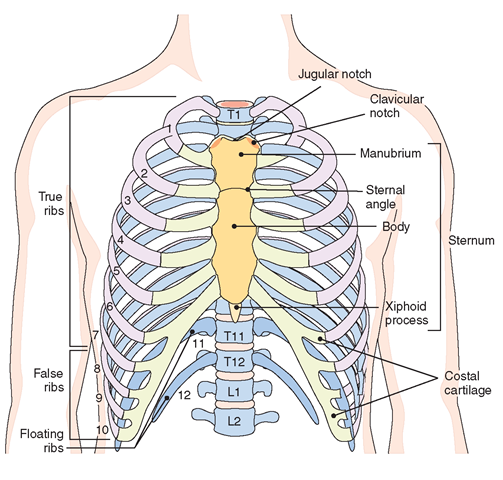

The thorax (chest) is a cavity formed by 12 pairs of flat, narrowed bones, the ribs (costae) (Fig. 18-10). The ribs form the thoracic or rib cage and protect internal structures such as the heart, lungs, liver, and great thoracic blood vessels. Ribs are arranged in pairs, 12 on each side. From their attachment to the spine at the back, the ribs curve out and to the front like hoops. The relatively elastic cartilage on the ends of ribs provides room for the chest and the abdomen to expand. The thoracic cage is also a supportive structure for the bones of the shoulder girdle. The floor of the thorax is the muscular diaphragm.

The first seven pairs of ribs, the “true ribs” or vertebrosternal ribs, are attached posteriorly to the thoracic vertebrae and anteriorly to the sternum. The next three pairs, the “false ribs” or vertebrocostal ribs, are also attached to the vertebrae posteriorly. However, they are joined only to each other anteriorly, via the costal cartilages. The last two pairs of ribs are considered “false ribs,” but are also known as “floating ribs” or vertebral ribs, because they are only attached posteriorly to the vertebrae and are not attached to each other.

The front boundary of the upper part of the thorax is the sternum or breastbone, a flat, sword-shaped bone in the middle of the chest opposite the thoracic vertebrae in the back. The sternum consists of three sections: The manubrium is at the top; the body of the sternum is in the middle; and the xiphoid process projects out at the bottom.

The Appendicular Skeleton

The appendicular skeleton is composed of the bones of the upper and lower extremities and pelvic girdle (see Fig. 18-1).

Upper Extremities

The upper extremities include the shoulders and arms. Four bones form the shoulder girdle, which anchors the arms. Two long, thin bones, the clavicles (collar bones), are attached to the sternum and extend outward at a right angle to it on either side. Opposite the clavicles on each side of the back is a scapula, or shoulder blade. A scapula is a flat, triangular bone attached to the outer end of the clavicle on the skeleton. It attaches to the trunk of the body medially with the manubrium of the sternum. The structure of the scapula gives the body free movement of the shoulders and arms.

The humerus is the largest long bone found in the upper arm. The upper end is attached to the scapula, and the lower end meets the two forearm bones to form the elbow joint. (Each long bone is wider at the ends and thinner in the middle, providing strength where it meets another bone.)

FIGURE 18-10 · Bones of the thorax (anterior view). The first seven pairs of ribs—true ribs; pairs 8 through 12—false ribs (the last two pairs are floating ribs). The sternum is the structure shown in yellow. The thoracic vertebrae are indicated here and numbered T, TM, and T12· Li and L2 are lumbar vertebrae.

The forearm has two bones which lie beside one another. The larger one is the ulna and the smaller one is the radius. There are two hollows, or depressions, in the upper end of the ulna. Into one of these depressions fits the lower end of the humerus. Into the other depression fits the upper end of the radius. Both radius and ulna are attached to the wrist bones to form the wrist joint. The arrangement of these bones allows the palm to be turned forward (supine position, supination) or backward (prone position, pronation). The radius and ulna move so freely with the wrist bones and each other that when the palm turns down, the radius crosses the ulna (see Fig. 18-5).

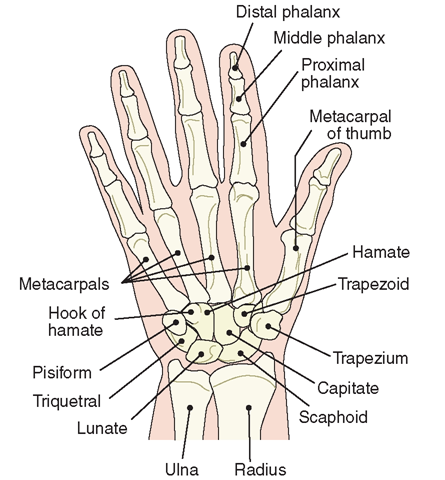

The many small bones in the hands and wrists allow for a great range of motion, such as twisting, bending, grasping, and squeezing. These bones enable human beings to perform such activities as playing musical instruments, writing, and picking up minute objects with the thumb and forefinger.

Key Concept More than one quarter of the bones in the body are in the hands and wrists.

Figure 18-11 depicts the bones of the hand. The eight carpal bones, or wrist bones, are small, irregular bones that support the base of the palm. They are attached to the radius, the ulna, and five long, slender, and slightly curved metacarpal bones forming the palm of the hand. The other ends of the metacarpals attach to the phalanges, or finger bones. Three phalanges are in each finger and two in each thumb, with joints between each phalanx. (Any bone of either a finger or a toe is called a phalanx.)

Lower Extremities

The femur (thigh bone) is the upper bone of the leg. The body’s longest and strongest bone, it supports the weight of the upper body.

FIGURE 18-11 · Bones of the right hand, anterior (palmar) view. The wrist contains 8 carpal bones. The hand contains 5 metacarpals, and 14 phalanges. The total number of bones in both hands is 54.

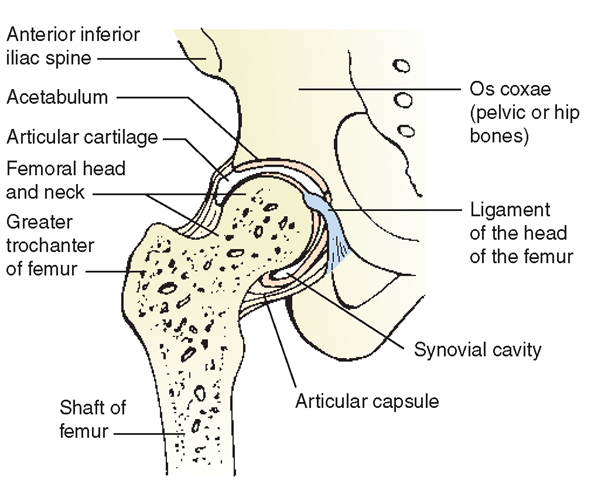

FIGURE 18-12 · Hip joint. Section through right hip joint, showing insertion of head of femur into the acetabulum.

The lower end of the femur is attached to the tibia of the lower leg at the knee joint. The upper end of the femur, described as the head, is attached to the pelvic bone in a ball-and-socket joint, where its rounded head fits into a depression called the acetabulum (Fig. 18-12). The head of the femur joins the shaft of the femur by a short length of bone called the neck. (This area is a common site of fractures, particularly in older adults.) Elevations on either side of the junction of the shaft and the neck, called the trochanters, serve as points of muscle attachment.

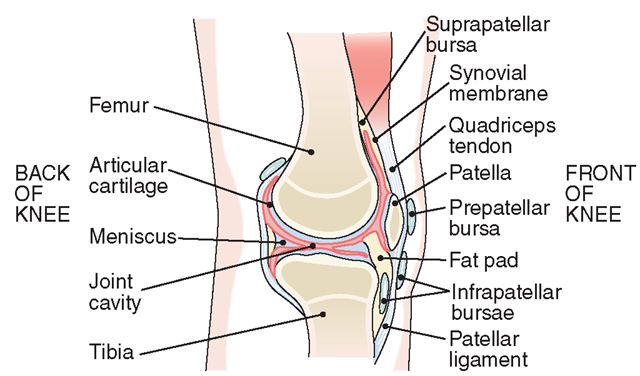

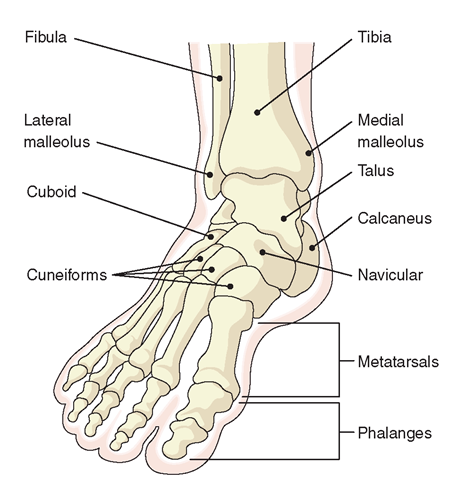

There are two bones in the lower leg: the tibia, or shin bone, and the fibula. The tibia is the long weight-bearing bone of the lower leg. The upper end of the tibia is attached to the lower end of the femur at the knee joint (Fig. 18-13). A small bone, the patella (kneecap), protects the front of the knee joint and is buried in a tendon that passes over the joint. The lower end of the tibia meets the bones of the ankle and the fibula to form the ankle joint. A protrusion on the lower end of the tibia can be felt on the medial side of the ankle. This is the medial malleolus.

The fibula, which is smaller than the tibia, is attached to the tibia at its upper end. The fibula is not a weight-bearing bone and is not part of the knee joint. The lower end of the fibula is a part of the ankle joint. Similar to the medial malleolus of the tibia, another projection called the lateral (side) malleolus is located where the distal end of the fibula meets the ankle bones.

The foot is constructed to support the weight of the entire body and still to provide flexibility and resilience (Fig. 18-14).

FIGURE 18-13 · Knee joint (sagittal section).

FIGURE 18-14 · Bones of the right foot.

The seven tarsal bones of the ankle are compact and shaped irregularly; the largest of which (the calcaneus) is in the heel. The tarsal bones join the five metatarsal bones (instep bones) to form two arches: the longitudinal arch, which extends from heel to toe; and the transverse or metatarsal arch, which extends across the foot. The weight of the body falls on these arches, and the many joints spring and give when a person walks. Weak muscles lessen this spring, and high spiky heels and poor posture upset the body balance, flattening the arches. The 14 bones of the toes, the phalanges, are attached to the metatarsals. The big toe has two phalanges; each of the other toes has three.

In general, the hands and feet are built alike, but the bones of the hands are finer and the joints are more numerous (27 bones are in each wrist and hand, 26 in each ankle and foot). The hands are designed for fine and flexible movements; the feet are designed for support.