Learning Objectives

1. On a chart, trace the digestive pathway, naming the major organs of the gastrointestinal (Gi) system and the function of each.

2. Define the following terms and processes: mastication, deglutition, and peristalsis.

3. Explain the actions of hydrochloric acid (HCl), gastrin, intrinsic factor, cholecystokinin, and pancreatic juice in the process of digestion.

4. Explain two functions of the pancreas and gallbladder as they relate to digestion.

5. Describe the functions of the liver related to digestion.

6. Describe the physiology of digestion and absorption, including how carbohydrates, fats, and proteins are broken down; describe absorption in the small intestine.

7. Identify and describe two major categories of metabolism.

8. Explain how the large intestine changes its contents into fecal material.

9. Describe the effects of aging on the digestive system.

|

IMPORTANT TERMINOLOGY |

||

|

absorption |

egestion |

peritoneum |

|

alimentary canal |

emesis |

pyloric sphincter |

|

appendix |

esophagus |

pylorus |

|

bile |

feces |

rectum |

|

bolus |

gallbladder |

rugae |

|

cecum |

gingiva |

saliva |

|

chyme |

ingestion |

salivation |

|

colon |

jejunum |

sphincter |

|

defecation |

lacteal |

tongue |

|

deglutition |

liver |

villi |

|

dentin |

mastication |

|

|

digestion |

micelle |

|

|

duodenum |

oral cavity |

|

|

dysphagia |

peristalsis |

|

|

Acronyms |

|

|

ATP |

HCl |

|

CCK |

LES |

|

CHO |

|

The body needs a constant supply of energy to perform its many tasks. These actions are possible because the digestive system converts the food eaten into fuel for the body’s energy demands. In a lifetime, the human digestive system will process about 50 tons of food!

The mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into usable materials for energy is called digestion. During digestion, food is broken down into smaller elements, a form of catabolism. The process of transferring these food elements into the circulation for transport is called absorption. After absorption, the elements are carried to the body’s cells to be used for energy and building cells; an example of anabolism. The physiology of digestion and absorption is discussed near the end of this topic.

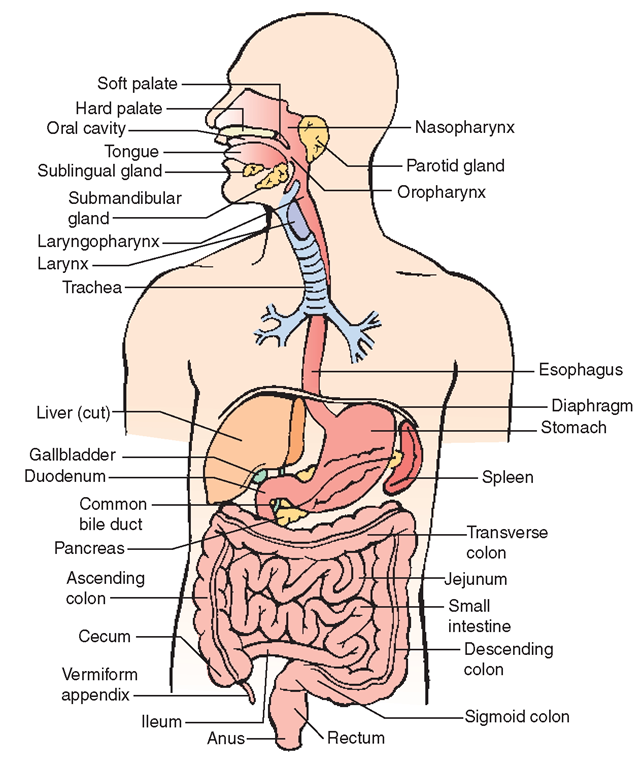

The efficient food-processing machine responsible for digestion and absorption is called the digestive tract. It is also called the alimentary canal, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and GI system. (The specialty concerned with study of the stomach and intestine is gastroenterology.) The GI tract or canal is like a tube, approximately 28-30 feet (9.1 m) long;it runs through the body and is open to the outside at both ends (mouth and anus—see Fig. 26-1).

FIGURE 26-1 · The digestive system.

Food travels through the GI tract in about 24-36 hours. The final stage of digestion is elimination (egestion, defecation). The actions of the digestive system are controlled by the nervous system. The endocrine system also exerts a major influence.

Key Concept Because the GI tract is open to the outside, and because non-sterile material is introduced into it (food), it is not considered to be sterile.

Elements broken down by digestion to provide fuel for the body are called nutrients. These nutrients are carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. They consist of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen; proteins also contain nitrogen.

Structure and Function

Figure 26-1 shows the major organs of the digestive system. Table 26-1 summarizes the structures making up the digestive system. The main function of the overall digestive system (Box 26-1) is to break down food into simpler forms that the circulatory vessels can carry and pass through the cell membranes to the cells. The cells then use these food molecules or nutrients for energy and to build, maintain, and repair body tissues.

MOUTH

The mouth is also called the oral cavity. Food is taken into the body through the mouth, where digestion begins. This is called the cephalic phase of digestion. Here, the teeth cut,chop, and grind food so the food particles become smaller and more of their surface can be exposed to the actions of digestive juices and enzymes. The mouth’s chief digestive functions are to receive food via ingestion (to take in), to prepare food for digestion, and to begin the digestion of starch.

TABLE 26-1. Intestinal Structures, with Approximate Lengths

|

STRUCTURE |

LENGTH |

|

Pharynx |

5 inches |

|

Esophagus |

10 inches |

|

Stomach |

|

|

Small Intestine |

About 20 feet total |

|

Duodenum |

10-12 inches |

|

Jejunum |

8 feet |

|

Ileum |

11 feet |

|

Large Intestine |

About 5 feet total |

|

Cecum |

2-3 inches |

|

Colon |

4-4.5 feet |

|

Rectum |

5 inches |

BOX 26-1.

Functions of the Digestive System

Food Processing and Storage

♦ Breaks down food into smaller particles (mechanical digestion)

♦ Converts food into substances that can be absorbed (chemical digestion)

♦ Moves food materials through the gastrointestinal tract (peristalsis)

♦ Stores nutrients until needed

Manufacture

♦ Manufactures enzymes, hydrochloric acid, intrinsic factor; mucus, and other materials to assist in digestion

♦ Manufactures regulatory hormones in stomach

♦ Manufactures vitamin K and some B-complex vitamins in large intestine

Absorption

♦ Provides absorption of nutrients, mainly from small intestine, into capillaries

Reabsorption and Elimination

♦ Reabsorbs water for reuse by the body

♦ Reabsorbs minerals and vitamins

♦ Forms feces from remaining waste products

♦ Produces defecation

Palate

The roof of the mouth is made up of the hard and soft palates. The hard palate is close to the front of the mouth and is composed of the palatine bones and parts of the maxillary bones. The soft palate is mostly muscle tissue. It separates the mouth from the nasopharynx. The soft palate is shaped like an arch in the back of the mouth, and opens onto the oropharynx. The structure that can be seen suspended in the back of the open mouth is the uvula. The tongue covers the floor of the mouth. The walls of the mouth cavity are the cheeks and the teeth.

Salivary Glands

When a person sees or thinks about food, the salivary glands begin to function, making the “mouth water.” Three pairs of salivary glands pour 1-1.5 L of saliva into the mouth each day. The names of these glands indicate their locations: sublingual (under the tongue), parotid (cheek), and submandibular (under the lower jaw). The salivary glands are exocrine glands because their secretions are not directly released into the circulation but are released into the oral cavity. There are two types of saliva. One is thin and watery and serves to wet the food and make it easier to swallow. The other is a thicker, mucous secretion that contains mucin,which lubricates and also causes food particles to stick together to form a bolus (ball or lump) of food. Saliva contains ptyalin, also called salivary amylase. Saliva also contains water, mucus, and salts. The nervous system controls the secretion of saliva (salivation).

Special Considerations :LIFESPAN

Prolapsed Glands

Prolapse of the submandibular glands may occur in older adults and could be mistaken for a tumor Unlike tumors, however, these drooping submandibular glands feel soft and are seen on both sides of the neck.

Through the action of ptyalin, saliva begins to break down starch (polysaccharides) into smaller sugar molecules. Saliva helps prevent oral infections because it contains lysozymes (bacteriocidal enzymes) and immunoglobulins (IgA). The pH of saliva is normally about 6.8 (very weak acid). Saliva also assists with speech and taste.

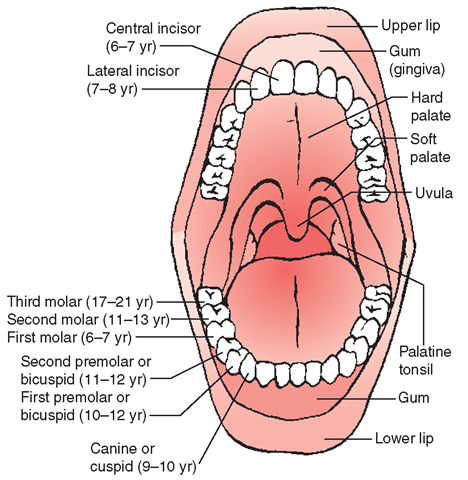

Teeth

The teeth are set in spaces or sockets in the upper and lower jaw bones—the maxilla and mandible. The chief function of teeth is to break food into smaller particles, which is accomplished through mastication, the act of chewing. Humans have two sets of teeth: the deciduous (“falling out”) or “baby teeth” and a permanent or adult set (Fig. 26-2). A baby’s deciduous teeth usually begin to erupt between 6 and 8 months of age, and the 20 teeth are usually complete by 30 months of age (see Fig. 10-3). At the age of about 6 years, children’s permanent teeth begin to appear. As the permanent teeth grow in, they push out the deciduous teeth, replace them, and fill in the spaces in the jaw. The permanent set has 32 teeth.

FIGURE 26-2 · The adult mouth, showing the teeth and tonsils. Approximate ages for eruption of permanent teeth are shown.

Types and Locations

The teeth are named and located as follows:

• The sharp, flat incisors are the front teeth. They cut and tear food.

• The pointed canines or cuspids are the side teeth. They hold and tear food.

• The bicuspids (premolars) and molars crush and grind food.

• The last permanent teeth, the third molars or wisdom teeth, sometimes do not appear before adulthood. They are located in the far back of the mouth. If a person’s jaws are small and jaw space limited, the wisdom teeth may not have room to erupt and may become impacted in the bone or tissue. Impacted wisdom teeth often require surgical removal.

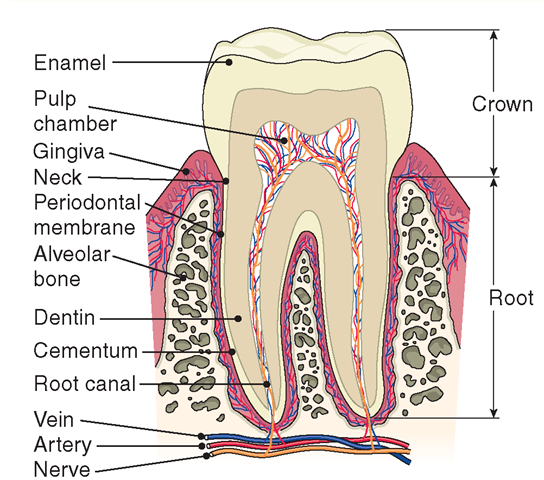

Parts

A tooth has three parts: crown, neck, and root (Figure 26-3). The crown is the enamel-covered part of the tooth visible in the mouth. (Tooth enamel is the hardest structure in the body.) The tooth narrows into a neck at the gum line. (The gum is also known as the gingiva.) The root of the tooth is in the bony socket. A substance called cement (or cementum) covers the root. Beneath the enamel and the cement is a hard bonelike substance called dentin, which is the bulk of tooth material. The tooth’s center is the pulp cavity (pulp chamber). The pulp contains many nerve endings and blood vessels, which enter through the roots (via the root canal) from the tooth sockets. The teeth are embedded in and nourished by bone.

Key Concept When tooth decay is so advanced that it permanently damages the pulp, a root canal procedure or removal of the tooth (extraction) is required.

FIGURE 26-3 · A tooth.

Tongue

The tongue is a tough skeletal muscle covered with smooth mucous membrane. It is attached to four bones: the mandible, two temporal bones, and the hyoid. On the bottom of the tongue is a fold of mucous membrane called the frenulum. This structure helps to attach the tongue to the floor of the mouth.

Key Concept In some cases, the frenulum is short or too tightly attached.This makes speech difficult, and the person is said to be "tongue-tied.” This situation can easily be surgically corrected.

The tongue has several functions. It senses the temperature and the texture of food. It mixes food with saliva, and moves food into position to be chewed. The voluntary movement of the tongue begins the swallowing process, called deglutition, by pushing food into the pharynx, the next portion of the digestive tube.

The upper surface of the tongue appears rough because of visible indentations (fissures) and projections (papillae). The taste buds are microscopic nipple-like projections located on the sides of the papillae. They are specialized nerve endings that allow detection of various flavors. The taste buds distinguish among flavors. Although all types of taste buds are found on most areas of the tongue, they are concentrated as follows: salty (tip and sides of the tongue), bitter (back of the tongue), sweet (tip of tongue), and sour (sides of tongue). Alkaline and metallic flavors are sometimes considered distinct flavors as well (see Fig. 21-6). Remember that a person’s ability to taste food also depends on the sense of smell. (Smoking decreases both taste and smell.)

Key Concept Oral mucosa on the underside of the tongue is very thin and contains many blood vessels. This allows substances to be absorbed when placed under the tongue (sublingual). Sublingual medications are immediately absorbed into the blood stream, without requiring processing by the GI system. An example is nitroglycerin, to treat angina pectoris (sudden acute chest pain caused by decreased cardiac blood supply).