Learning Objectives

1. Identify and describe the following types of wounds: abrasion, puncture, laceration, and surgical incision.

2. Describe the concept of skin breakdown, including the causes, most common locations, and staging of pressure ulcers.

3. Describe the evaluation of risk factors for skin breakdown and how these data are used.

4. Describe nursing measures that help prevent skin breakdown.

5. Describe procedures and equipment used to care for a pressure ulcer or other open wound.

6. Describe the three types of wound healing.

7. Explain three purposes of wound dressings.

8. Demonstrate how to change a dry, sterile dressing, and describe how to apply a wet-to-dry dressing and irrigate a wound.

9. Describe common types of wound drainage systems, including VAC.

10. Describe how sutures and staples are removed.

|

IMPORTANT TERMINOLOGY |

|||

|

abrasion |

exudate |

puncture |

undermining |

|

debridement |

friction |

sinus tract |

venous stasis ulcer |

|

decubitus ulcer |

granulation |

shear |

wet-to-dry dressing |

|

diabetic ulcer |

laceration |

slough |

wound |

|

drain |

packing |

surgical incision |

|

|

drainage |

pressure |

suture |

|

|

eschar |

pressure ulcer |

tunneling |

|

Acronyms

ABD

IAD

NPUAP

VAC

WOCN

The skin acts as a barrier to protect the body from the potentially harmful external environment. When the skin’s integrity (intactness) is broken, the body’s internal environment is open to microorganisms that may cause infection. Any abnormal opening or break in the skin is a wound. It is an important nursing responsibility to inspect the client’s skin carefully on admission to a facility, and frequently thereafter for any signs of pressure or skin breakdown. It is vital to prevent skin breakdown and, if it occurs, to report it immediately and treat it as ordered.

WOUNDS

A wound is described as a physical injury causing a break in the skin or mucous membrane. The most common types of wounds are trauma (accidental or self-inflicted) wounds, surgical incisions, and several types of ulcers. (An external ulcer is a defect or break in the skin produced by sloughing away of dead inflammatory tissue. Ulcers may also occur in mucous membranes.) Other types of skin abnormalities include infections, rashes, lesions, and burns.

A wound may be accidental or unintentional, such as an abrasion (rubbing off of the skin’s surface [e.g., a skinned knee]); a puncture wound (stab wound); or a laceration (wound with torn, ragged edges [e.g., an accidental or selfinflicted cut]). A non-self-inflicted wound may be intentional, such as a surgical incision (a wound with clean edges). A wound that occurs accidentally or that is selfinflicted is assumed to be contaminated; intentional surgical incisions are made under sterile conditions and are kept as free from microorganisms as possible (Fig. 58-1).

FIGURE 58-1 · Types of wounds. (A) A surgical incision is an intentional wound. Here, the edges are brought together and stapled. (B) A surgical incision closed with sutures (stitches).(C) An unintentional wound, shown here, results from trauma. Open unintentional wounds have a high risk of infection.

Inspection and Description of Wounds

Skin inspection includes visual inspection as well as palpation, with special emphasis on body prominences, and careful and accurate documentation. Inspection sites include the back of the head, ears, heels, coccyx, shoulder blades, elbows, and so on, as well as insertion sites, such as those for intravenous (IV), nasogastric (NG) tubes, or tracheostomy tubes (see Fig. 58-4). Note whether the skin blanches when pressed, or if it remains red or discolored. Prediction of possible skin breakdown is discussed later in this topic.

Nursing Alert Do not massage any discolored or reddened pressure points. Rationale: This can add to the irritation and accelerate skin breakdown.

Special Considerations: CULTURE & ETHNICITY

Skin Observation: Color Changes Caused by Pressure Areas or Ulcers

Darkly pigmented skin—damage may show as purplish, bluish, or gray Olive tone skin (Hispanic, Indian, Southern European, Middle Eastern)—not likely to have red tones—compare with surrounding skin or opposite side Lightly pigmented skin—defined area of persistent redness

Wounds are diagnosed by the primary healthcare provider in a number of ways. Vascular (blood vessel) ulcers may be evaluated by using angiograms or the laser Doppler. Laboratory testing, including biopsy and wound culture, yields information about the cause and treatment of a wound. It is important for the nurse to observe and describe all wounds carefully, including pressure ulcers and surgical incisions. In Practice: Data Gathering in Nursing 58-1 lists items that must be addressed for all wounds. Be sure to document and report all observations. (Computer programs usually contain a template for wound evaluation—this ensures consistency between caregivers.) See In Practice: Nursing Procedure 58-1 to review steps for inspecting, cleaning, and dressing a wound.

Nursing Alert Avoid inspecting wounds under fluorescent lights when observing for wound/skin color Rationale: Fluorescent lights may create an incorrectly diagnosed abnormal skin color or may mask variations in the client’s skin tone.

Drainage

Discharge from a wound is called drainage. Wounds, particularly unintentional wounds, often have drainage. Drainage containing a great deal of protein and cellular debris, usually as a result of inflammation, is called exudate, although the term exudate is sometimes used to denote any drainage. The nurse is often required to perform wound care and apply dressings to manage drainage. When performing wound care, the nurse must be able to describe drainage accurately. Types of drainage:

IN PRACTICE DATA GATHERING IN NURSING 58-1

DESCRIBING A CLIENT’S WOUND

Clearly describe a wound by including the following:

• Exact anatomic location (e.g., include distance in centimeters [cm] or millimeters [mm] from wrist, elbow, knee, etc.)

• Duration of wound (how long has it been there?)

• Exact dimensions: width, length, and depth (in mm/cm). Measure depth with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator

• Color and appearance of wound bed and of surrounding (peri-wound) tissue (closed or rolled, open, calloused, macerated, color)

• Presence of undermining or tunneling tracts

• Specific appearance of areas of the wound, identified by using the hands of the clock as a reference

• Extent of tissue loss; percentage of each type of tissue (granulation, subcutaneous, muscle, eschar leathery slough)

• New tissue formation in margins; appearance of wound edges

• Presence or absence of exudate (drainage) and its description (odor, amount, color, general appearance)

• Feeling of warmth, coldness, hardness, softness, and other observations around wound

• Subjective complaints (and description) of pain, tightness, itching, or other symptoms

• Presence of any foreign bodies (sutures, staples, gauze, dressings, medications)

• Diagram of wound, if irregular in shape

• Other objective assessments (e.g., body temperature, blood tests)

• To determine changes in skin color and possible areas of damage, look at surrounding skin for comparison or compare one side of the client’s body to the other (e.g., one buttock to the other)

• In addition to skin color, other signs of damage may include skin that is tender indurated (swollen), boggy or edematous to palpation.

• Serous: made up of serum; clear, thin, and watery

• Serosanguineous: composed of serum and some blood

• Sanguineous: bloody, containing a great deal of blood and some serum

• Purulent: containing pus

• Color (e.g., green, tan, yellow, red)

• Odor (e.g., malodorous, no odor, sweet-smelling)

Amounts of Drainage:

• None: dressings dry

• Scant: wound tissue moist, no exudates (visible drainage)

• Small: wound moist throughout, drainage on less than 25% of dressings

• Moderate: drainage on about 30%-60% of dressings

Special Considerations

All clients must have a complete skin inspection on admission to any nursing facility. This must be carefully documented. (In some facilities, Psychiatric and Obstetric clients are exempt, unless a wound is obvious.) Skin inspection must be performed on a regular basis thereafter, per facility protocol, and documented carefully (to monitor for any sign of skin breakdown). Any skin breakdown or apparent infection must be reported immediately.

• Large/copious: wound tissues saturated; drainage on more than 60%-75% of dressings.

• In some cases, dressings are weighed to determine the exact amount of drainage.

NCLEX Alert This topic provides you with information on your role in inspecting your client’s skin integrity and gives suggestions for describing wounds in your documentation. This information may be integrated into the test scenarios and will need to be considered as you answer test questions.

Other Characteristics of Wounds

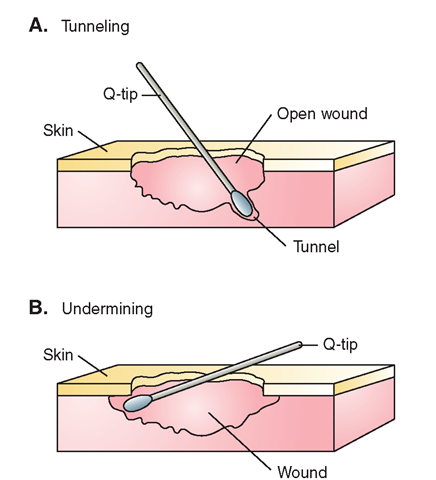

Tunneling. Tunneling refers to the presence of one or more channels within or underlying an open wound. Each tunnel extends in only one direction. The depth of a tunnel is measured by inserting a sterile cotton-tipped applicator into the tunnel and then measuring the distance it was inserted (Fig. 58-2A).

Undermining. If tissue recedes beneath the skin, creating a shelf or free edge with a space underneath, this is referred to as undermining (Fig. 58-2B). The distance the undermining extends behind the edge of the shelf of skin is also measured with a sterile applicator and documented (see also Fig. 58-3C).

Wound Edges. The appearance of the wound edges should be documented. For example, they may be rolled under— the top layer of the epidermis is rolled down over the lower edge of the wound (closed), macerated (softened by moisture), or calloused (very hard, yellow to white). The wound edge may be open, that is, the edge looks healthy, with evidence of tissue growth at the rim.

Periwound Area. Note the appearance of the area around the wound. Descriptive terms include the following: intact, pink, erythema (redness), excoriated (scratch or abrasion), blistered, ecchymotic (a hemorrhagic spot, blue or purple),denuded (skin stripped away), blistered, macerated, and many others. Include a descriptive comment, if necessary. Wound Base. In some cases, the wound base cannot be visualized. Otherwise, describe the color, character, and appearance of the wound base. Does it contain granulation tissue, slough, or eschar? Does it appear moist or dry? Is it beginning to resurface? Describe the color and percentage of different types of tissue.

FIGURE 58-2 · (A) Tunneling is measured by inserting a sterile cotton-tipped applicator into the tunnel and measuring the distance of insertion. Each tunnel is measured and documented separately. (B) Undermining is also measured using an applicator Usually. the undermining extends around the entire circumference of the wound, although the extent of the undermining may vary.

Wound Measurement. There are a number of ways in which wounds may be measured. These include:

• Linear measurement—a ruler is used to measure the width and length of a wound. This does not measure wound depth and is not well-suited to an irregular wound.

• Planimetry—graph paper is used to duplicate the shape of a wound. This can allow a large, irregular wound to be drawn to scale and is best used for a flat wound. Be sure to indicate the scale used (e.g., 1 cm = 1 inch).

• Stereophotogrammetry—a special video camera downloads to a computer. This method allows color images and is noninvasive. It also gives some indication of wound depth.

• Wound photography—photos of the wound illustrate the color of the wound bed and its edges, as well as giving an indication of the condition of surrounding skin.

• Wound tracing—transparent paper may be laid over the wound and the edges lightly traced. This is effective for flat, irregular wounds.

Additional description of wounds is contained in the discussion of pressure ulcers below.

Causes of Skin Breakdown

Disruption of skin integrity or non-intact skin, commonly called skin breakdown, is a potential complication for any client confined to a bed or wheelchair. This includes the person with a body cast, traction, or the person who is paralyzed or otherwise cannot move without assistance. In other cases, skin breakdown can occur as a result of factors such as moisture, external pressure, infection, or rash, even in the ambulatory client. A common cause is shearing force (friction) caused by clothing, bed linens, or client safety devices. Conditions contributing to skin breakdown are:

• Immobility, low level of activity (lying/sitting in one position for extended periods of time, paralysis)

• Inadequate nutrition (very thin person; inadequate protein, insufficient calories)

• Hydration levels (inadequate fluid intake, excess fluid retention—edema)

• Presence of external moisture (including perspiration, urine, and feces); incontinence

• Impaired mental status, alertness, or cooperation; heavy sedation and/or anesthesia

• Sensory loss

• Fever; low blood pressure (particularly diastolic <60 mm)

• Advancing age, friable skin

• Infancy

• Impaired immune system (AIDS, cancer chemotherapy)

• Presence of cancer or other neoplasms

• Circulatory disorders; anemia

These factors are to be considered for any client in the healthcare system. Good nursing care can alter some of these factors, to prevent skin breakdown. The client with a history of skin breakdown is particularly vulnerable.

NCLEX Alert It will be important for you to understand causes of skin breakdown and types of wounds/ulcers as they relate to client teaching and nursing actions to prevent skin and tissue damage. For example, you may be asked to select the appropriate nursing actions to prevent the development of pressure ulcers during your NCLEX examination.

Types of Skin Breakdown

The discussion of unintentional wounds in this topic is based, in large part, on prevention and treatment of skin breakdown and decubitus or pressure ulcers.

• Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD). The client who is incontinent of urine or stool must have meticulous skin care, to prevent skin breakdown. Table 58-1 compares this condition with the pressure ulcer.

Key Concept IAD can be prevented by using an incontinence cleanser (e.g., Remedy Spray Cleanser; which does not dry skin) and a moisture barrier paste (e.g., Calazime, which protects skin) before damage occurs. Disposable paper washcloths should be used instead of cloth washcloths; dispose of them in the trash—do not flush. Do not use Bag Bath or shaving cream, which can irritate and dry out the skin.

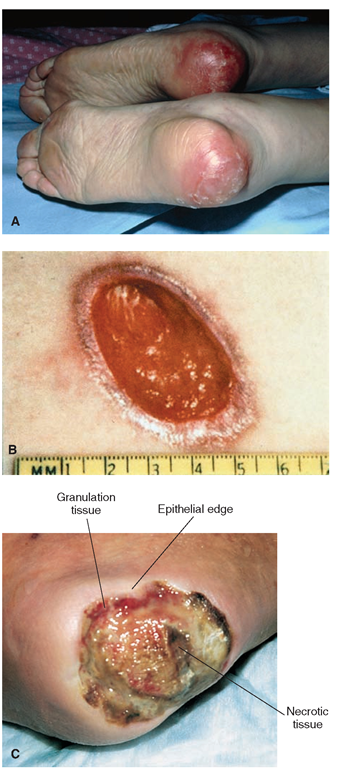

• Pressure ulce . This ulcer, also known as a decubitus ulcer (plural: decubiti), is a localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue, usually over a bony prominence. Most often this is caused by pressure or pressure combined with shear and/or friction. Pressure causes a disruption in circulation, leading to tissue death (necrosis). Friction is the rubbing of one surface against another and shear is the interaction of friction and gravity when tissue is moved across a material. Some of the stages of a pressure/decubitus ulcer (formerly called bedsore or pressure sore) are pictured in Figure 58-3. The stages and treatment of pressure ulcers are discussed later in this topic.

TABLE 58-1. Differences Between Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis and Pressure Ulcer

|

INCONTINENCE-ASSOCIATED DERMATITIS |

PRESSURE ULCER |

|

|

Cause |

Moisture |

Pressure or rubbing |

|

Prevention |

Meticulous skin care; keep client clean and dry |

Prevent pressure areas, turn often, and so forth |

|

Location |

May be located anywhere on the body |

Usually on a bony prominence or area that rubs |

|

Pattern of Redness |

Diffuse; extends to perineum and upper thighs |

Surrounding the pressure area only |

|

Tissue Loss |

Usually limited to dermis and epidermis |

May extend to muscle and bone |

FIGURE 58-3 · Stages of pressure ulcers (see also Box 58-1). Stage I (reversible) includes pressure-related changes in intact skin, when compared with adjacent skin (not shown). Some pressure ulcers are not stageable. The pressure ulcers shown here are (A) Stage II: partial-thickness tissue loss. No sloughing; may appear as blister: (B) Stage III: full-thickness tissue loss, with subcutaneous damage and drainage. May show tunneling or undermining. (Note procedure for measuring size of ulcer.) (C) Stage IV: full-thickness tissue loss, extensive destruction of muscle, bone, or other structures. Note undermining shown on upper edge of wound.

Key Concept Prevention of pressure ulcers and other skin breakdown is a primary nursing responsibility

In addition to pressure ulcers, two other skin ulcerations may occur:

• Venous stasis ulcer (venous insufficiency ulcer)—these ulcers develop most often in the lower extremities. They are the result of local hypoxia (lack of oxygen) to specific tissues. A number of theories exist to their cause, including poor oxygen diffusion into the tissue, venous congestion caused by overly large white blood cells, and the inability of cells in the affected area to obtain appropriate growth factors.

• Diabetic ulcers—these ulcers (also called diabetic neuropathic ulcers) may occur in persons who have diabetes mellitus, partly as a result of impaired circulation. Persons with diabetes often are slow to heal, and these wounds may be difficult to treat.

Although there are a number of causes of skin breakdown or disruption of skin integrity, many wounds are treated in a similar manner.

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers are usually the result of pressure on the skin, in excess of that which a particular client’s skin and underlying tissue can safely tolerate. Skin pressure, combined with the contributing factors listed above, make the person susceptible to skin breakdown. Some body areas, including bony prominences (e.g., shoulder blades, elbows, coccyx, hips, knees, sides of the ankles, and back of the head), as well as areas, such as the heels and ears, are more likely to break down than are others (Fig. 58-4). These areas are not covered by the pads of fat that normally cushion blood vessels. When blood vessels are compressed and blood flow is reduced, oxygen supply diminishes, skin breaks down, and the tissues beneath are destroyed (tissue necrosis). Insertion sites of tubes can also become irritated and contribute to skin or mucous membrane breakdown.

NCLEX Alert Be alert to the classification of pressure ulcers as well as the objectives of wound care. You may be asked to demonstrate your knowledge in the NCLEX examination.

An ulceration can also develop in an obese person, under pendulous breasts or abdominal folds. This type of wound is often complicated by a yeast infection. It is important to keep all these areas as clean and dry as possible.