Choosing a Healthcare Provider

Preconceptional and prenatal care, at its best, is a partnership between the woman and the healthcare provider. The woman should choose a provider who will help her make decisions about the best healthcare for herself and her family. Above all else, the provider should be someone who genuinely listens to the woman and her concerns.

A woman may choose a physician, a nurse midwife, or a nurse practitioner for her prenatal care. She may go to a public health clinic, a private office, or a community-based organization. Each of these sites and providers has strengths and limitations. Some examples of questions a woman might ask as she selects a prenatal care provider include:

• Do I want a male or a female provider?

• Should my provider speak the same native language that I do?

• When I have a question or concern about my pregnancy, will my provider talk with me about it?

• Is the location convenient? How will I get to the provider’s office? Will I walk, drive, or take the bus?

• Is the staff courteous, friendly, and respectful toward me?

• Do I have a choice of the hospital at which I’ll give birth?

• Are there other services (e.g., dietitian or social worker) available to me through my provider?

• Can my partner come with me for my prenatal visits?

After a woman has chosen a provider, she will have her initial preconceptional or prenatal visit. When possible, the woman’s partner should be encouraged to accompany her on the first visit to the practitioner. If the partner is the child’s father, he can provide the practitioner with important information about his medical history and any genetic concerns he may have. Any partner who is present to learn important facts about pregnancy will also be in a better position to support and encourage the woman who is expecting. A partner’s presence is helpful at subsequent visits, also, to allow the couple to hear and discuss information together.

Components of Prenatal Care

There are three basic components of adequate prenatal care:

1. Early and regular prenatal care

2. Maintenance of maternal health; promotion of good health habits

3. Recognition and treatment of physical, mental, and social/economic problems

Risk Assessments

The goal of risk assessment is to identify women and fetuses who have a chance of having a complication develop during pregnancy, labor, birth, or the neonatal period. After a risk is identified, the healthcare team can provide the appropriate type and level of care, which results in better outcomes. There is no perfect risk-assessment system.

The best health for mother and baby results when the mother has her first visit before the end of the first trimester (before the end of week 13) and then has regular visits until after she has delivered the baby. The usual timing for visits is about once every 4 weeks for the first 28 weeks, then every 2 weeks until 36 weeks, and then weekly until the birth. The postpartum visit is usually scheduled at 4 or 6 weeks after birth, although many providers also like to see the woman at 2 weeks postpartum.

The Initial Prenatal Visit. The following are key components of the initial prenatal visit.

• Health history: The provider takes a complete health history of the woman and her partner, if possible, to learn about past illnesses and any pattern of certain inherited diseases that might affect this pregnancy (e.g., Tay-Sachs, diabetes, or sickle-cell anemia). The provider is also interested in learning whether a multifetal pregnancy (twins or more) has occurred in either family. The physician, nurse midwife, or nurse practitioner needs to know if the woman has had any difficulties during previous pregnancies or births, or if she has had any serious infections, including STIs or HIV. It is also important to assess the woman’s lifestyle, including risk due to infections, substance use, or domestic violence. A thorough health history provides an accurate record of the client’s past and present health and gives the provider important data.

• Physical examination: A complete physical examination, including a pelvic examination, is part of the initial prenatal visit. This head-to-toe assessment includes examination of the gums, teeth, thyroid gland, heart, lungs, breasts, and all body systems. Also, the woman’s height and weight should be measured and recorded at the first prenatal visit. During the pelvic examination, the provider checks the reproductive organs for signs of pregnancy, the bony pelvis for approximate size and shape, and looks for indications of any health problems. Pelvic measurements help in determining whether the bony passageway is large enough for delivery of a normal-sized newborn, an especially important consideration in a primigravida. A Pap test and STI tests (gonorrhea and chlamydia) are also routinely performed as part of the pelvic examination.

• Laboratory tests: The woman’s blood type and Rh factor are determined. If the woman is Rh negative, she should receive Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM, Gamulin Rh) at the 28th week of gestation and following any episode of bleeding or any invasive procedure (e.g., amniocentesis). The purpose of giving RHOGAM is to prevent Rh isoimmunization.

• Other blood tests that are routinely obtained include a syphilis test (RPR or VDRL), complete blood count (CBC), antibody screen, and rubella titer. A rubella titer is done to determine if the woman is immune to rubella, or German measles. If she is not immune, she is not vaccinated during pregnancy because the rubella vaccine is live and could possibly have a harmful effect on the fetus.

• HIV testing should be offered to every pregnant woman, according to the Institute of Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. If a woman tests positive for the virus and begins treatment for HIV during the pregnancy, the risk of transmitting the virus to the fetus drops significantly.

• In addition to a pregnancy test (if it is needed to confirm the pregnancy), the woman’s urine is tested for albumin (protein), glucose, and the presence of harmful bacteria. Each time a urine sample is collected from a pregnant woman, she should be helped to obtain a clean-catch specimen.

• The pregnant woman should be given a Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST), which is the standard test for tuberculosis. The TST determines if an individual is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Refer to the latest Fact Sheet information on TB, pregnancy, and testing procedures on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Website.

Nursing Alert The TST contains 0.1 tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) given intradermally into the inner surface of the forearm. A specific tuberculin syringe must be used with the needle bevel facing upward. Correct procedures of administration and reading are necessary. The TST must be read between 48 and 72 hours later. In reading the test, only the raised area, not the reddened area, should be measured. A normal response may produce a pale elevation or wheal of 6 to 10 mm in diameter; erythema (redness) is not measured.

• If the woman or the baby’s father has a family history of genetic problems, a referral for genetic counseling and testing should be given to the couple.

• Determining the baby’s due date: A woman who thinks she is pregnant is wise to consult a healthcare provider after she has missed one menstrual period. A full-term pregnancy is approximately 280 days from the first day of the last menstrual period, or 266 days after fertilization.

IN PRACTICE :DATA GATHERING IN NURSING 65-2

DETERMINING THE ANTICIPATED DATE OF BIRTH OR DUE DATE

Pregnancy is dated from the first day of the woman’s last normal menstrual period (LNMP). To be considered normal, the period should have:

• Come on time

• Lasted as long as is usual for her

• Have been the normal flow for her

If any of these three items is not true of that period, ask her to recall the first day of her previous menstrual period (PMP).

When you have an accurate date for her last period, the due date for the baby is determined either by using a gestational wheel or by applying Nägele’s rule. The due date is usually called the estimated date of confinement (EDC) or the estimated date of delivery (EDD).

NÄGELE’S RULE

• Determine the date of the first day of the woman’s LNMP

• Add 7 days.

• Subtract 3 months.

• The resulting date is the EDD.

The 280 days equal 40 weeks. Many women do not keep an accurate record of their menstrual periods or may not have regular periods for many different reasons. In these cases, the practitioner determines the estimated date of delivery (EDD), also called the estimated date of confinement (EDC), based on the size of the uterus during the physical examination, and/or by an ultrasound estimate of fetal age. See In Practice: Data Gathering in Nursing 65-2 for more information on determining the anticipated birth date. The actual duration of pregnancy varies greatly, and the EDD is an approximate due date. Only about 4% of women actually deliver on their EDD.

• Initial risk assessment: The provider determines the degree of risk to the woman and fetus based on information from the history, physical examination, laboratory results, and due date. Commonly used terms for risk status are low risk and high risk. Although there is certainly such a thing as moderate risk, it is very hard to define. Based on her risk assessment, an individualized plan of counseling, classes, referrals, and prenatal care appointments is developed with the pregnant woman.

Return Prenatal Visits. At each return appointment, also called a revisit, the following measures should be performed and charted by a member of the healthcare team:

• Weight: This reading is then compared with her prepregnancy weight and her previous weight measurements.

• Blood pressure

• Urine: A “dipstick” analysis is performed for protein, glucose, and sometimes nitrites and leukocytes (indicators of bladder infections).

• Uterus: Measurement of the size of the uterus, called fundal height, and an evaluation of its growth since the last visit are performed.

• Fetal heart tones

• Edema: Check the face, hands, legs, and feet for edema.

• Continuing risk assessments: At each prenatal visit, the risk profile should be updated. If new information indicates a change in the woman’s risk status, the provider will develop a new plan of care with her to address her needs.

The client should be asked about any problems or complications that she has experienced since her last visit; how she is feeling; whether she has any concerns or worries; and how often the fetus is moving (after quickening has occurred).

Additional Tests Performed During Pregnancy. Many women have an ultrasound examination done between 16 and 20 weeks of pregnancy. This is a very accurate time at which to determine gestational age and also to examine the fetus for normal development. If there is a problem or a concern at a different point during the pregnancy, the ultrasound examination may be repeated.

Between weeks 15 and 19, a blood test called the maternal serum alpha fetoprotein (MSAFP) is done. The primary purpose of this test is to screen for fetal neural tube defects. It may be combined with two other tests (HCG and estriol), which increases the number of neural tube defects that may be identified and also screens for Down syndrome. This test is called a triple marker screen.

Between 24 and 28 weeks, all pregnant women should be screened for diabetes. The test used during pregnancy is a 1-hour random glucose tolerance test. The woman eats normally until her prenatal or laboratory appointment, then drinks a 50-g glucose beverage. Her blood is drawn 1 hour later to be tested for glucose. Elevated glucose levels may indicate gestational diabetes.

The Rh antibody test is repeated at 26 to 27 weeks, and RHOGAM is given at 28 weeks if the antibody test remains negative (In Practice: Important Medications 65-1).

IN PRACTICE :IMPORTANT MEDICATIONS 65-1

RH IMMUNE GLOBULIN (RhoGAM)

Microdose: 50 mcg (used after spontaneous or elective abortion at <13 weeks’ gestation)

Full dose: 300 μg at 28 weeks’ gestation

Expected effect: In an Rh-negative woman, RhoGAM prevents antibodies to Rh-positive fetal blood cells from forming. The 28-week dose provides protection for about 12 weeks; another dose should be given after delivery

Adverse side effects: Pain, soreness at injection site nursing considerations

• RhoGAM should also be given if an Rh-negative woman has any bleeding during the prenatal period or if she has invasive testing performed, such as chorionic villus sampling or an amniocentesis.

• RhoGAM is a blood product, but unlike whole blood or red blood cells, it is a processed immunoglobulin. It is safe for pregnant women to use. The method of its preparation includes viral inactivation. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is not a concern with this blood product.

• Because RHoGAM is a blood product, women who do not take blood products for religious reasons may refuse to take it.

Many providers repeat STI testing at 36 weeks, and may also do a vaginal culture for group B streptococcus.

Health Promotion

Health promotion through education of the pregnant woman is recognized as an important aspect of prenatal care. Although pregnancy is a normal, albeit unusual, event in a woman’s life, the changes in her body and her sense of being may come as a shock to her.

In many societies, sexuality and pregnancy are two topics about which caregivers provide very little real information. Much of what is learned about these important aspects of life is mythological or “old wives’ tales.”

In addition, the scope of knowledge about how to nurture a growing fetus has changed dramatically over the past 30 years. About a generation ago, the first solid recommendations regarding nutrition during pregnancy were published; fetal alcohol syndrome was recognized as a preventable disorder; and information about sexuality in pregnancy became available.

Culturally, the feminist movement and the self-care movement worked together to empower women to demand additional knowledge about pregnancy. This includes information about changes within the body, how to improve the chance of having a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby, and how to deal with the emotional and psychological processes involved in pregnancy.

The combination of these three factors—an inadequate amount of culturally acquired knowledge about pregnancy, an increase in scientifically acquired knowledge, and the pregnant woman’s own increased desire to learn about and be an active participant in pregnancy—results in a clear need for health promotion during pregnancy.

Elimination and Hygiene. A daily bowel movement is preferable for the pregnant woman, although not all women normally have one. A woman who has a tendency toward constipation may face increased difficulties during pregnancy, due to decreased peristalsis. Plenty of water, fruits, vegetables, moderate exercise, and adequate fiber intake encourage regular elimination.

The body’s oil and sweat glands are more active than usual during pregnancy, so a daily warm (not hot) bath or shower is important. No proof exists that a tub bath is harmful at any time during pregnancy. Of course, the woman must be careful not to slip or fall in the tub or shower. During the last few weeks of pregnancy, the woman should not take a tub bath if she is home alone because she may have difficulty getting out of the tub and may require assistance. The woman’s hair may be oilier than usual and may need frequent shampooing. A woman may safely use hair coloring or permanent waving during pregnancy.

The pregnant woman should practice good oral hygiene. The woman who eats a balanced diet and sees her dentist regularly does not need to worry about tooth damage during pregnancy. Necessary dental work should be performed and sources of infection treated. Many dentists do not want to perform oral surgery (e.g., root canal) on pregnant women, unless it is an emergency.

Some women experience an increase in salivation, called ptyalism, during pregnancy. Although annoying to the woman, ptyalism does not cause tooth decay or gum irritation.

Some women are advised by nonprofessional sources, such as mothers or aunts, to douche during pregnancy. This practice is not only unnecessary, but can be harmful. If there is an infection with an odor or itching, the woman should be checked for a vaginal infection. Douching can actually increase her risk of vaginal infection and sometimes can cause an existing infection to be pushed up into the cervix and uterus. Pregnant women should be advised not to douche.

Breast Care. Except for the use of a supportive bra, elaborate breast care is unnecessary before breastfeeding. Studies show that complicated nipple preparation rarely makes a difference in successful breastfeeding. A woman who is considering breastfeeding may decide against it if she is presented with a list of nipple exercises and special creams and ointments she is required to purchase. Women who plan to breastfeed should bathe as usual and use little or no soap on the nipples. They should gently pat their nipples dry. The nipple secretes its own natural moisturizer, which should not be removed with soap or other chemicals. Women should also avoid applying alcohol, tincture of benzoin, and lanolin ointments. These substances may damage the areola and nipple and have not been shown to be effective in preventing sore and cracked nipples. Lanolin is also a common allergen and may contain insecticide residuals and DDT.

Wearing a nursing bra with the flaps down and exposing the nipples to air and sunshine may help to condition them. Harsh treatment may cause sore and cracked nipples and should be avoided. Nipple exercises and stimulation should not be done, especially in the third trimester, when they can cause uterine contractions and premature labor. Flat nipples should be treated with breast shields that are worn during the last trimester and after delivery between feedings. Inverted nipples are rare and can be treated with a nipple shield.

Rest. The pregnant woman tires more easily and should have enough rest to avoid fatigue. Preventing fatigue is better than having to recover from it. The woman should know how much rest she ordinarily requires and plan to get more if needed. Going to bed earlier, getting up later, or taking an afternoon nap may help. Short daytime rest periods are beneficial if the woman really relaxes. Pregnant women are able to carry on normal household activities without harm if they avoid heavy work and get additional rest.

As pregnancy advances, the woman may have a hard time finding a comfortable sleeping posture. Simple measures, such as additional pillows at the back, or a pillow supporting the weight of the abdomen or the top arm while the woman lies on her side, will usually relieve these common problems.

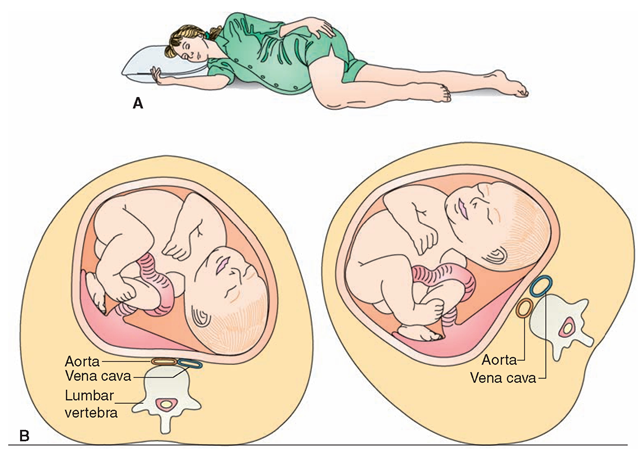

During the pregnancy’s last months, the woman should rest on her left side for at least 1 hour in the morning and afternoon (Fig. 65-11). (This position relieves fetal pressure on the renal veins, helps the kidneys excrete fluid, and increases flow of oxygenated blood to the fetus.)

Advise the pregnant woman not to sleep or lie on her back to avoid supine hypotension syndrome (aortocaval compression). The weight of the uterus can interfere with the circulation in the aorta and the vena cava, thus depriving the woman and the fetus of oxygen (Fig. 65-11B). If the woman must remain on her back, place a small pillow or towel roll under one hip. The goal is to keep the woman’s circulation unimpeded by displacing the weight of the uterus to the side, rather than on the major blood vessels.

Exercise and Posture. Exercise improves circulation, appetite, and digestion; it also aids in elimination and helps the woman to sleep better. The woman may safely continue customary exercises.

Swimming in a pool can be beneficial; however, swimming in lake water in later stages of pregnancy is not advised because of the danger of infection.

FIGURE 65-11 · (A) Rest position during pregnancy. The knees and elbows should be slightly bent, the muscles limp, and the breathing slow and regular Notice that the weight of the fetus is resting on the bed. (B) Supine hypotension syndrome can occur if a pregnant woman lies on her back, trapping blood in her lower extremities. If a woman turns on her side, pressure is lifted off of the vena cava.

Specific prenatal exercises are a part of childbirth education. Walking in fresh air is excellent exercise. Whatever the exercise, it should not be fatiguing. Exercise should be daily, rather than sporadic (see In Practice: Educating the Client 65-2 and 65-3).

Activity. Weight gain, stability, or loss involves the balance between energy sources (diet and stored fuel) and energy expenditure. Energy use in this energy equation is the combination of basal metabolic rate, body heat production, and physical activity.

IN PRACTICE :EDUCATING THE CLIENT 65-2

Exercise Guidelines during pregnancy

The goal of prenatal exercise is physical fitness within the limitations of pregnancy If a woman does not have contraindications to exercising during pregnancy these general guidelines should be followed:

• Women with uncomplicated pregnancies can continue a moderate exercising program, with these modifications:

• Reduce the intensity of the exercise by about 25%.

• Maximum maternal heart rate should not exceed 140 bpm.

• Periods of strenuous activities should be limited to 1520 min, interspersed with low-intensity exercise and rest periods.

• Extremely active women, athletes, and women who perform vigorous aerobic exercise should reduce the level of exertion.

• Sedentary women should begin to exercise very gradually.

• The types of exercise that provide the best cardiovascular and psychological benefits throughout pregnancy are walking, cycling, and swimming.

• Relaxation and stretching exercises (yoga) may be continued throughout pregnancy Muscle strengthening exercises, such as Kegel exercises to strengthen the pelvic floor and pelvic tilts or pelvic rocks to strengthen the lower back and relieve back pain, may be done by all pregnant women. These provide no cardiovascular benefits.

• Jogging and weight-bearing aerobic programs should be moderated to avoid injury caused by ligament relaxation and increased joint mobility during pregnancy.

• Women who lift weights may continue to lift light weights during pregnancy, with the following modifications:

• Avoid heavy resistance on machines.

• Avoid use of heavy free weights.

• Breathe properly to avoid the Valsalva maneuver.

• Sports that pose a potential risk to the mother or fetus include:

• Contact sports—football, soccer

• Sports involving potential joint or ligament damage— basketball, volleyball, gymnastics, downhill skiing, skating

• Horseback riding

• Sports that are safe to continue during pregnancy include:

• Racquet sports—tennis, racquetball, squash (avoid heat stress; decrease intensity as pregnancy progresses)

• Golf (may need to modify golf swing)

• Slow-pitch softball (avoid sliding into bases, blocking bases)

• Cross-country skiing

• Avoid any strenuous exercise or sport in adverse conditions— extreme heat, high humidity, air pollution, high altitudes.

IN PRACTICE :EDUCATING THE CLIENT 65-3

EXERCISE IN PREGNANCY: DANGER SIGNS

A pregnant woman who is exercising should be alert to the following signs and symptoms. If these occur, she should stop exercising, and contact her healthcare provider.

• Pain of any kind

• Uterine contractions (occurring at intervals of fewer than 15 min)

• Vaginal bleeding; leaking amniotic fluid

• Dizziness; faintness

• Shortness of breath

• Palpitations; tachycardia

• Persistent nausea and vomiting

• Back pain

• Pubic or hip pain

• Difficulty in walking

• Generalized edema

• Numbness in any part of the body

• Visual disturbances

• Decreased fetal movement

The average total additional energy (calorie) requirement is about 2,500 to 3,500 calories per day. Changes in daily physical activity are individual, leading either to an increase or a decrease in energy used throughout the pregnancy.

Special Considerations :CULTURE & ETHNICITY

Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy

Traditionally, Puerto Rican families view exercise during pregnancy as inappropriate. Contrast that with Haitian women (who are not relieved from their responsibilities, and are expected to fulfill their obligations throughout the pregnancy) and pregnant Cambodian women, who are also active.

Sexual Relations. Pregnancy, although usually a result of sexual activity, is not viewed as a sexual state in our society. Although certain individuals may consider the sight of a pregnant woman beautiful and erotic, she may be seen as misshapen, awkward, and not particularly arousing. In the last decades of the 20th century, pregnancy has commonly been viewed as natural, sensual, and beautiful.

Pregnancy is always a time of challenge to a relationship, both developmentally and sexually. The challenge can result in either crisis or growth.

During pregnancy, a woman continues to have sexual needs. If the pregnant woman has a partner, the partner also continues to have sexual needs. Both partners have needs for intimacy and closeness, which may differ from their sexual needs. Intimacy needs can be categorized into the following three groups:

• Sexual needs: The sex drive, or libido, usually changes during pregnancy—although the pattern of the change in libido is quite individual. In addition, the sexual response cycle is affected by pregnancy. These changes, combined with the changes in anatomy and physiology during pregnancy, have varying effects on the relationship of a pregnant couple. Sexual needs may be met through sexual activity with a partner or masturbation. Some women experience spontaneous orgasm due to the increased pelvic blood supply during pregnancy. Pregnancy diminishes sexual desire in some women and increases it in others. Communication between the pregnant woman and her sexual partner helps to eliminate conflicts.

• Touch needs: Pregnancy is a time of a heightened need for touch, which may be met partially by sexual expression, but which can also be met through nonsexual touch, such as massage, caressing, or holding.

• Comfort and reassurance needs: The need of the pregnant woman for comfort and reassurance stems both from her changing body image and from the developmental processes of pregnancy. These factors bring fears and concerns for the pregnant woman about safety for herself and the fetus, her desirability, and her need for continued love and support.

Sexual Safety During Pregnancy. In general, expressions of sexuality during pregnancy are quite safe. Sexual intercourse is often physically difficult and awkward late in the pregnancy, and couples may wish to experiment with a variety of positions and sexual practices. Sexual intercourse during pregnancy is not harmful as long as it is not unduly uncomfortable and no high-risk factors are present (e.g., placenta previa, preterm labor, or ruptured membranes). There are a few exceptions to this rule, and these risks can be categorized by the causative factor. Categories of risk include:

• Risk due to penetration: Women who experience bleeding during pregnancy should avoid vaginal penetration until the problem is diagnosed.

• Risk due to possible infection: There are two primary areas where infection is a risk with sexual activity: sex with a partner who has a STI; and sex after the rupture of membranes, which normally protect the fetus and placenta from infection.

• Risk due to arousal: For a woman at risk for preterm labor, sexual arousal, and the accompanying increased engorgement of the pelvic organs, might stimulate the initiation of labor. There is no proof that arousal increases the risk of spontaneous abortion. Sexual arousal may be used at term to initiate labor—at this point in the pregnancy, it is no longer a risk.

• Risk due to orgasm: The uterine contractions that occur with and follow orgasm may stimulate preterm labor.

• Risk due to sexual behaviors: With the exception of STI exposure, the main risky sexual practice during pregnancy is the forceful blowing of air into the vagina, which may result in air embolism.

Clothing. By about the third month, the pregnant woman will discover that her clothing is becoming tight, and she needs to wear looser clothing. Some women wear special maternity clothing; others opt for bigger and looser versions of normal, everyday clothing (e.g., oversized sweaters, elas-ticized pants and skirts). Garters, constrictive knee socks, and knee-high pantyhose should not be used because they restrict blood flow. Women should wear comfortable shoes;flat heels are less awkward and provide a better base of support. The pregnant woman will probably have difficulty tying shoelaces or fastening buckles late in the pregnancy.

The pregnant woman should wear a wide-strapped bra that supports the breasts without causing nipple pressure. An underwire bra is usually more comfortable for the woman with heavy breasts. A good nursing bra is essential after delivery if the woman plans to nurse. She should purchase two or three bras of her normal chest size but with a larger cup size.

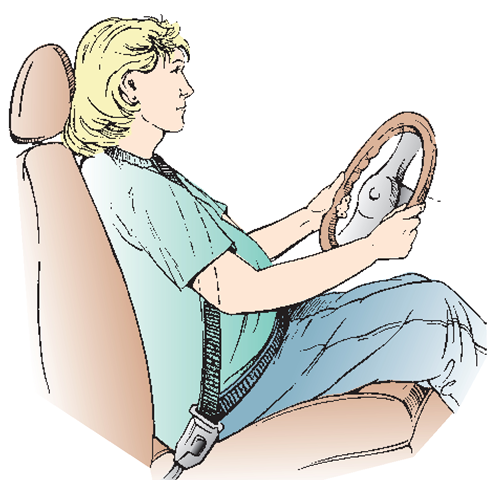

Travel and Employment. Most women continue driving during pregnancy, at least until the last months, when it may become uncomfortable (the fetus, woman, and steering wheel cannot occupy the same space at the same time). The woman must be sure to buckle her seatbelt under her enlarging abdomen. She should use the shoulder strap, placing it to the side of her abdomen (Fig. 65-12). Seatbelts are particularly important during pregnancy to protect the woman and the fetus. A car with air bags provides added protection.

Long trips are exhausting for anyone, but because today’s families are often on the move, the pregnant woman may find regular travel necessary. Travel by air or train is recommended for long, tiring trips. If the woman is to travel by car, she should plan to stop at least every 2 hours to go to the bathroom, stretch, relax, and walk around for at least 10 minutes. This movement helps to prevent blood from pooling in the lower extremities. The pregnant woman should never fly in a small plane that is not pressurized because the lower atmospheric pressure decreases the supply of oxygen to the fetus. The expectant woman should consult with her healthcare provider about travel plans because special conditions and times during pregnancy may rule out traveling. A long trip away from home when the woman is close to term is also unwise.

Many women continue to work outside the home during pregnancy. The law states that in most situations, a maternity leave of absence, without loss of seniority, must be granted to a woman who requests one. Jobs that involve heavy lifting, operating dangerous machines, continuous standing, or working with toxic substances are contraindicated during pregnancy. Radiation should also be avoided.

FIGURE 65-12 · Pregnant women should wear a seat belt with the shoulder strap above the uterus and below the neck, and a lap belt low and under the abdomen.

Teratogenic Factors. Some fumes, chemicals, substances, and infections are known to cause fetal defects. These environmental, damaging agents are called teratogens. Most teratogenic effects occur in the first trimester of pregnancy, during the critical period of development of the embryo. The woman may not even know yet that she is pregnant.

Teratogenic events occur after fertilization and are not genetic (inherited), although they are congenital (present at birth). Maternal dietary deficiencies and food, air, and water pollutants may play a role. Radiation is particularly dangerous.

The following are some examples of teratogens:

• Diseases: Rubella, herpes, toxoplasmosis, syphilis. To avoid the infection of toxoplasmosis, the pregnant woman should not handle cat litter and should cook meat well, especially poultry. She should wash her hands carefully after handling raw meat and wash all raw fruits and vegetables thoroughly before eating them. She should wear gloves while gardening or cleaning.

• Prescribed medications: Phenytoin, lithium, valproic acid, isotretinoin, and warfarin have each been associated with teratogenesis.

• Substances of abuse: The provider should obtain a complete substance use history at the first preconceptional or antepartum visit. If the mother uses tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drugs, she is strongly advised to stop. Street or recreational drugs, such as amphetamines and stimulants, can cause fetal difficulties. The danger seems to be greatest early in pregnancy. Alcohol is the most widely used substance, and also the most damaging to the fetus. Heroin can cause congenital addiction. Cocaine may be associated with long-term behavioral and attention problems in the child born to a mother who used it during pregnancy. Other recreational drugs are either known or suspected teratogens.

• Ionizing radiation: This is the type of radiation exposure that is used in treating cancers, or that occurs with a nuclear plant accident.

Nursing Alert Caution the pregnant woman not to take any herbs, drugs, or medications without asking the healthcare provider Laxatives, diuretics, stimulants, and depressants are particularly dangerous. Many herbs also are not proven safe for the fetus.

Nursing Alert If you suspect any type of drug abuse in a pregnant woman, notify the healthcare provider

Nutrition During Pregnancy. One of the earliest and most important purposes of prenatal care has been to counsel women and ensure that they receive adequate nutrition to support themselves and their growing fetus during pregnancy. Studies show that a newborn’s chances for good health are greater with a reasonably high birthweight. The nutritional requirements of a pregnant woman differ from those of a nonpregnant woman. The woman’s caloric needs increase during pregnancy because she needs to meet energy requirements for fetal, placental, and maternal tissue development. The quality of the diet, not the quantity, matters most, and the pattern of weight gain is more important than the total amount.

To obtain the necessary distribution of nutrients, foods for the pregnant woman should be selected from all food groups. Exclusion of any group may lead to a deficiency of one or more nutrients. The guidelines for pregnant women are basically the same as the general guidelines for healthy eating. It is suggested that the pregnant woman increase her intake of milk and milk products. The pregnant woman should make the following dietary adjustments:

• Increase caloric intake by approximately 300 calories daily.

• Increase calcium intake before the last half of the pregnancy. Increase milk intake to 3 to 4 cups daily. Supplemental calcium is sometimes prescribed. (Rationale:Calcium is essential to the development of the fetus’ bones and teeth and for blood clotting.)

• Maintain iron intake. Most providers order an iron supplement during pregnancy because of its dietary importance. (Rationale: Iron is essential in the production of hemoglobin. Because breast milk contains little iron, the developing fetus stores iron for use after birth.)

• Maintain folic acid intake. Taking 400 μg daily of folic acid (folate) in a supplement is recommended for all women of childbearing age when not pregnant, in addition to food sources of folate. During pregnancy, the recommendation increases to 600 mcg from a supplement, plus food sources. Most prenatal vitamins contain 1 mg of folic acid. (Rationale: Folic acid, a B vitamin, helps to prevent congenital neural tube defects, most notably spina bifida.)

• Increase intake of most vitamins. Many physicians prescribe supplemental vitamins during pregnancy.

• Increase protein intake. (Rationale: Protein is essential to the building and repair of all body tissues, and aids in the production of milk for the nursing mother.)

• Avoid empty calories, including alcohol, sugared soda drinks, other sweets, and salty foods.

• Use iodized salt. (Rationale: It promotes proper functioning of the thyroid gland.)

• Eat a wide variety of foods. (Rationale: A variety of foods will encourage proper nutrition, especially during the first few months of pregnancy if the woman is experiencing nausea.)

• Avoid laxatives and enemas unless the physician specifically orders them. Stool softeners, such as docusate sodium (Colace), are ordered more often than laxatives. Fiber is also essential to prevent and to treat constipation.

• Increase fluid intake to 10 glasses daily to assist in kidney and bowel function. Water is the preferred fluid.

When providing prenatal nursing care, keep in mind a woman’s general health, age, cultural and religious background; and her likes and dislikes, food allergies or sensitizations, and socioeconomic status. These factors will affect her diet and pattern of weight gain. Dietary counseling should begin at the first visit and continue throughout all follow-up visits. Instructing the client to make a sample diet for review is useful in determining needed dietary changes.

Appetite. Changes in the woman’s body during the early part of pregnancy may interfere with her appetite, so attention must be given to supplying her with proteins, vitamins, and iron throughout pregnancy.

Many pregnant women find that they are extremely hungry after the first few weeks. They should monitor what they eat and be careful not to fill up on empty calories. Rich, highly spiced, and fried foods are undesirable. In the late months of pregnancy, several small meals daily, rather than three large ones, will probably help her feel better. The pregnant woman will not have as much space in her abdomen for a distended stomach.

Beverages and foods that contain caffeine can be harmful to the pregnant woman. Items containing caffeine include coffee, some teas, most cola drinks, several other soft drinks, and chocolate (in candy or in beverages). Caffeine may contribute to mastitis, an inflammation and swelling of breast tissue in the woman that can cause irritability in the fetus, especially if the mother is breastfeeding. Caffeine also crosses the placenta during pregnancy.

Pica is an abnormal craving for nonfood items during pregnancy, such as clay, dirt, and cornstarch. If left untreated, pica can lead to serious nutritional and other physical disorders.

Weight Gain During Pregnancy. The recommended weight gain for each woman depends on her height and what she weighed before she got pregnant. This comparison, known as the body mass index (BMI), provides a starting place to determine how much weight is ideal to gain during this pregnancy. At the initial prenatal visit, the client’s height and weight will be measured. She will be asked what she weighed prior to pregnancy. Finally, a BMI chart will be used to determine whether she is underweight, of average weight, overweight, or obese.

The pregnant woman’s weight should increase gradually from the sixth week after conception until the end of the full term.

Compare the variables of maternal body size (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese) and the variables of weight gain during pregnancy (low or high). Recommended weight gain during pregnancy is based on these body size variables. Not only do maternal prepregnant body size and weight gain in pregnancy affect birthweight, but they also have an impact on perinatal mortality. For women who are underweight, the risk of perinatal mortality at term is lowest if they gain at least 37 pounds. For women of normal weight before pregnancy, the perinatal mortality rate is lowest with a weight gain between 30 and 37 pounds. For obese women, the perinatal mortality begins to increase with a weight gain of more than 15 pounds.

Key Concept All pregnant women should gain weight.

In assessing maternal weight gain, other helpful guidelines include the following:

• By the 20th week of gestation, all women, except obese women, will have gained approximately 10 pounds.

• Any woman who loses more than 8 pounds during the first trimester is at increased risk. Weight loss during pregnancy is never recommended.

• Although weight gain itself is critical, equally important is the quality of food leading to the weight gain. For example: A woman may easily gain weight on a cookie, chips, and soda diet, but may not be well-nourished.

Common Discomforts of Pregnancy. Even in normal pregnancy, it is common for the woman to have some unusual, and sometimes uncomfortable, sensations. These are the “common discomforts of pregnancy.” They are considered minor, not in the sense that they do not cause true discomfort, but because they are not serious and do not threaten the life of the fetus or the mother. However, sometimes it is difficult to tell what is truly a common discomfort or when a symptom may be a warning sign of a more serious problem. Table 65-1 describes the possible causes of many discomforts, suggestions that may decrease discomfort, and warning signs of more serious problems.

Key Concept It is important to differentiate a common discomfort of pregnancy from a warning sign of a complication.