Learning Objectives

1. Discuss the importance of assessing the safety of an emergency scene.

2. Describe how triage applies to emergency care.

3. Describe the medical identification tag and its purpose.

4. Describe, in order, the steps for assessing an ill or injured person in an emergency.

5. Identify early, common, and progressive signs of shock. Describe the common types of shock, including hypovolemic shock, identifying nursing actions in emergency-induced shock.

6. Describe general emergency actions for chest, neck, back, and head injuries.

7. Demonstrate in the laboratory, emergency actions for a chest puncture wound.

8. Discuss first aid for musculoskeletal injuries, including a fracture, demonstrating the ability to splint an ulnar or radial fracture safely using common household materials.

9. Describe the signs of increasing intracranial pressure.

10. Describe emergency care for different types of hemorrhage.

11. Explain symptoms and first aid for injuries caused by exposure to cold, including frostbite and hypothermia.

12. Describe symptoms and immediate first aid for heatrelated illnesses and injuries, including heat exhaustion and severe burns. List the signs of an inhalation injury following a fire.

13. Describe the immediate actions of a rescuer in suspected heart attack.

14. Describe causes, symptoms, and treatment of anaphylaxis.

15. Identify precautions to take when a client has been exposed to hazardous materials. List the immediate actions to take when a person is suspected of being poisoned.

16. List the factors that identify a psychiatric emergency or the potential for suicide.

17. State and demonstrate the procedure for calling a code in your healthcare facility or agency.

18. Describe the steps in Basic Cardiac Life Support,including cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

|

IMPORTANT TERMINOLOGY |

|

||

|

AMBU-bag |

dislocation |

intrusion injury |

stridor |

|

anaphylaxis |

epistaxis |

intubation |

sudden death |

|

antidote |

extrication |

mediastinal shift |

syncope |

|

avulsion injury |

fracture |

near drowning |

thrombolytic |

|

bandage |

frostbite |

pneumothorax |

tourniquet |

|

biological death |

heat cramps |

poison |

toxin |

|

café coronary |

heat exhaustion |

rabies |

trauma |

|

caustic |

heat index |

shock |

triage |

|

clinical death |

heat stroke |

splint |

wind chill factor |

|

code |

hemorrhage |

sprain |

|

|

debride |

hypothermia |

strain |

|

|

Acronyms |

|

|

ABCDE |

HAZMAT |

|

ACLS |

ICP |

|

AED |

LOC |

|

AVPU |

MAST |

|

BCLS |

MI |

|

BLS |

MVA |

|

CMS |

PERRLA+C |

|

CPR |

PTSD |

|

DNI |

RICE |

|

DNR |

SIRES |

|

EMS |

SIRS |

|

EMT |

Trauma refers to a wound or injury that is caused by an outside force. Thousands of people die from the effects of trauma and sudden illness every year. Traumatic injuries are caused by events such as motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), poisonings, burns, responses to temperature extremes, obstructed airways, and gunshot wounds. Events such as the tragic explosion and collapse of the World Trade Center towers in New York, Hurricane Katrina and other hurricanes on the Gulf Coast, and the collapse of the 35W bridge in Minneapolis emphasize the need for first-aid training for all healthcare workers, emergency and rescue personnel, law enforcement officers, and the general public.

This topic describes actions to take when caring for someone who has experienced sudden illness or trauma. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and basic life support are not described in detail in this topic. To learn the detailed methods used in CPR and removal of airway obstruction, the nurse must take a specific course. Healthcare facilities and organizations require CPR certification for all employees. It is up to each healthcare provider to take the responsibility for obtaining this training and to keep certification current. This topic briefly outlines measures in administering basic first aid for selected injuries and accidents.

PRINCIPLES OF EMERGENCY CARE

Simply because you are a nurse, people will expect you to be able to deal with emergencies. Good Samaritan Laws (Box 43-1) in most states and provinces require the nurse to assist at the scene of an accident in certain situations. Each nurse must be fully able to meet this expectation. Basic emergency care principles provide the foundation to act appropriately when accidents happen. In an emergency, the first responder must decide quickly what to do. For example, without adequate oxygen, a person’s brain cells begin to die within 4 to 6 minutes.

Therefore, you must give care in an emergency quickly. The stress level is usually high during an emergency, so having a predetermined, orderly plan of action and method of assessment is critical. It is also important to be able to reassure victims and onlookers and, in some cases, to enlist the assistance of others.

BOX 43-1.

Good Samaritan Laws

♦ Most states have a law that protects emergency care rescuers from legal liability, provided that the rescuers give reasonable assistance to the extent possible, without danger or peril to the person or themselves.

♦ Some states consider rescuers guilty of violating the law if they do not give aid to someone who needs it. In general, if emergency rescue personnel are already on the scene, you are not required to assist, unless you are specifically asked to do so.

♦ Nurses are required to assist in an emergency only to the level of first-aid training. Do only what you are trained to do in an emergency. Become familiar with the laws in the areas in which you work, live, and travel.

Assess Safety

Check to make sure the scene is safe before rushing to assist in an emergency. Is there any danger of fire, explosion, or building collapse? Is there danger of being caught in traffic or hit by a car? Are there electrical hazards, live wires, or other hazardous materials? Is the person in danger of drowning? If the scene is unsafe, the first responder may need to call for additional help before assisting injured persons. It may also be necessary to move victims away from danger before starting first-aid care. Do not move any injured person, however, if the area is safe. Rationale: Unnecessary movement can compound or cause additional problems.

Nursing Alert If the person is a victim of an automobile accident, remember to assign someone to direct traffic, to prevent further injuries.

Identify Problems

Is there anything unusual about the situation? Are containers lying about that suggest attempted suicide or poisoning? Do medications give a clue to a medical problem (e.g., diabetes, epilepsy)? Are there signs of alcohol or drug abuse? Is there any indication of foul play? Is the person wearing a medical information tag?

Key Concept If there is any indication of foul play, treat the victim without disturbing what has now become a crime scene.

When reporting an MVA, note the vehicle’s condition. Is the vehicle upside down, on its side, or in a ditch? Is the vehicle in the water? Is there a gasoline spill? Note areas of intrusion: the driver’s side, passenger’s side, roof, front end, or back end. Were victims wearing seat belts? Were the airbags deployed? Was anyone thrown from the vehicle; if so, how many feet or yards? If the victim was riding a bicycle or motorcycle, was the victim wearing a helmet and protective clothing? This information can help emergency personnel anticipate certain types of injuries.

MedicAlert Tag

It is important for any rescuer to check any nonresponsive victim for a medical identification (ID) tag or billfold insert. The most commonly used ID tag is the MedicAlert tag, which is used by more than 4 million people worldwide. This tag is worn as a necklace, bracelet, or boot tag and has an easily recognized symbol on the front (Fig. 43-1). It contains engraved information about the person on the back. About two-thirds of the tags contain condition-related information, such as diabetes, epilepsy, or high blood pressure. About one-third identify allergies, and a small number identify implanted devices, such as pacemakers. A 24-hour emergency number is available so rescue personnel can get vital medical information immediately, as well as an unidentified person’s identity, address, and information about next of kin.

FIGURE 43-1 · Emergency responders are required by law to check for MedicAlert or other emergency emblems as an indication of a nonresponsive victim’s identity and past medical history This is a patient directive that legally allows EMS to access the person’s stored medical information by calling the MedicAlert Foundation’s 24-Hour Emergency Response Center (1-800-625-3780 or the collect number on the tag). Each MedicAlert member has a unique secure patient identifier on the emblem, as well as other vital information. Additional information is on file at MedicAlert. Shown at left is the MedicAlert symbol, which appears on the front of the tag. In addition to specific medical information, signed documents, such as a living will, can be faxed immediately to the emergency staff.

In some states, the order “do not resuscitate” (DNR) can be engraved on the emblem and serves as the actual DNR order. It is also possible to call the MedicAlert Foundation to verify the client’s DNR status and obtain a faxed copy of a signed DNR order or other advance directive. A release for organ or tissue donation is also available by this means and also may be on the person’s driver’s license. (However, remember that if a person dies, his or her next of kin must give permission for organ and/or tissue donation, even if the person has been identified as a donor.)

Critical Access Standards

In 2005, The Joint Commission instituted Critical Access Standards for all rescue personnel. These standards state that healthcare facilities are required to store all critical client-provided information in the permanent client record. In addition, if a person is wearing emergency identification, healthcare and rescue workers are obligated by law to call for information if the client is unable to respond. (If this system is not activated by the healthcare facility in an emergency, this constitutes a sentinel event or critical incident and must be reported.)

FIGURE 43-2 · The E-HealthKEY is a thumb drive (flash drive) that can be used in any USB computer port. The use of this device often eliminates the need for the EMS to call for information and signed forms.

The E-HealthKEY

A device called the E-HealthKEY is also available from the MedicAlert Foundation. It is a thumb drive (USB drive) carried on a key chain (Fig. 43-2). This E-HealthKEY is a personal health record. Vital client information can be stored on this drive, which can be read in any USB computer port. In addition to demographic data (e.g., name and address), information that can be stored on the device includes the client’s medical history, medications and dosages, insurance information, and laboratory reports. The device is also capable of storing scanned documents and images for immediate retrieval. This might include the client’s electrocardiogram (ECG) or ultrasound or documents such as a living will, a signed donor release, or DNR forms.

Key Concept You, as a nurse, can encourage your friends, family and clients to wear a medical identification tag and, in the event of a serious health condition or, if the person travels extensively to carry the E-HealthKEY This may save their lives if they are in a serious accident or other life-threatening situation.

Perform Triage

Triage is the process of sorting and classifying to determine priority of needs.Triage involves determining life-threatening situations and assisting those clients first. If there are many victims, less seriously injured people may be able to assist others. It is also important to identify victims and their next of kin whenever possible.

The triage nurse and rescue personnel must determine whom to assist first, when and how to call for help, and how untrained bystanders can assist. For example, after the 35W bridge collapse in Minneapolis in 2007, bystanders were enlisted to help move victims quickly to safety. If there are numerous victims, the local hospital must be notified so that they can activate their disaster plan. Nurses also use triage in emergency departments (EDs) and clinics, whether through telephone screening or on a walk-in basis.

Summon Assistance

Summoning help is an important part of emergency care. A victim’s life may depend on rapid response. In most communities in the United States and Canada, the fastest way to summon the emergency medical service (EMS) is by telephoning 911. Be sure to know the local emergency number if it is not 911. If possible, send someone to call, but make sure the person has all necessary information, including the exact location and the nature of the emergency.

Assess and Treat for Shock

Shock is often the first phase of the body’s “alarm reaction” to trauma or severe tissue damage. Shock often occurs because the body loses its ability to circulate an adequate supply of oxygenated blood to all its components, particularly the brain. After an accident, many conditions can lead to shock; however, shock usually results from problems in the cardiovascular system.

The body attempts to compensate for any trauma or insult to its integrity. Because the central nervous system (CNS) controls all body functions, it monitors changes and immediately implements compensatory circulation to maintain an adequate blood supply to vital organs (e.g., the brain and the heart) in an emergency. This compensatory action can quickly adjust the rate and strength of the heart’s contractions and the tone of blood vessels in all body parts. It actually shuts down the flow of blood to the skin, digestive system, and kidneys, and shunts (transfers) blood that would normally go to these areas to the heart and brain instead. Compensatory circulation is a survival mechanism that ensures that the body’s most vital organs are adequately perfused with blood until the last possible moment. The symptoms of shock are largely related to this compensatory mechanism.

In some cases (e.g., when the injury is severe), the body cannot compensate and shock develops. Shock may develop rapidly following trauma (or more slowly in other situations). Consequently, every injured person should receive preventive and precautionary treatment for shock. Anything that could cause increased blood loss or otherwise contribute to shock should be avoided. For this reason, never handle or move injured persons unnecessarily and make every attempt to keep them calm.

Shock may fall into three major categories: primary—the nervous system’s response immediately after a severe injury or other traumatic event; secondary—one or more hours after an injury, perhaps up to 24 hours later (delayed or deferred shock); and hemorrhagic—caused by blood loss. The major types of shock, along with less commonly known types, are listed in Box 43-2.

Hypovolemic Shock

Absolute Hypovolemic Shock. Trauma that results in excessive blood loss will decrease the amount of blood volume available for the heart to pump. This will lead to a type of shock called absolute hypovolemic shock. It is most commonly referred to as just hypovolemic shock. The loss of about one-fifth of the body’s total blood volume can cause this type of hypovolemic shock.

In addition to hemorrhage, absolute hypovolemic shock may result from the following: severe dehydration (lowered intravascular [within the blood vessels] fluid volume), possibly, diaphoresis (excessive sweating) or diseases, such as diabetes insipidus and, in some cases, diabetes mellitus; severe diarrhea; protracted vomiting (over a long period of time); intestinal obstruction; peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum); acute pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas); and severe burns. Postpartum hemorrhage, which can cause hypovolemic shock, can occur as long as 6 weeks after delivery.

The signs of absolute hypovolemic shock include:

• Hypotension (lowered blood pressure, after a slight increase)

• Weak, thready pulse

• Cool, clammy skin

• Tachycardia (increased pulse)

• Tachypnea (increased respiratory rate)

• Hyperpnea (very deep breathing, gasping)

• Restlessness, anxiety (caused by decreased blood flow to the brain)

• Weakness

• Decreased urinary output

Remember, most of these signs and symptoms are related to the compensatory mechanisms of the body.

In the healthcare facility, additional information is obtained by diagnostic procedures such as monitoring of central venous pressure, pulmonary wedge pressure (PWP), and cardiac output; ECG; serum electrolyte levels; urine volume and specific gravity; arterial blood gases; and complete blood count. In shock, many of these values are abnormal.

Relative Hypovolemic Shock. Another type of hypovolemic shock, technically referred to as relative hypovolemic shock, is caused by widespread vasodilation (enlargement of the blood vessels of the body). This type of shock is caused by a massive infection or severe nervous system injury, rather than by hemorrhage.

In relative hypovolemic shock, blood volume is normal, but it cannot supply the tissues with adequate oxygen, because of the increased size of the blood vessels. The symptoms are largely the same as those seen in absolute hypovolemic shock.

Late Signs of Hypovolemic Shock. Later signs of hypovolemic shock include lowered body temperature, shallow respirations, and a narrowed pulse pressure (the difference between the systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings). If the shock is not successfully treated, the stage of decompensated shock occurs late in the process. The client in this stage is extremely hypotensive and the situation is particularly life threatening.

BOX 43-2.

Types of Shock

Major Types of Shock

♦ Anaphylactic (allergic) shock—severe, life-threatening reaction to a substance to which the client is sensitive or allergic. (See p. 513, Data Gathering in Nursing 43-1 for a list of symptoms of anaphylaxis.)

♦ Cardiogenic (cardiac) shock—primarily failure of the heart to adequately pump. The heart is severely compromised. Possible causes include: failure or stenosis (narrowing) of heart valves, cardiomyopathy (primary heart disease), or rhythm disturbances. Low cardiac output often results from an acute MI (heart attack) or heart failure. Cardiogenic shock may also occur in high cardiac output and is approximately 80% fatal.

♦ Electric shock—occurs after passage of electric current through the body. This usually results from accidental contact with electric circuits or wires, but may be caused by lightning. Damage depends on the pathway of the current, amount of current, and the skin’s resistance. Symptoms include unconsciousness, respiratory paralysis, tetanic muscle contractions (continuous tonic spasm), bone fractures, and cardiac standstill (cardiac arrest). Immediate defibrillation is often necessary.

♦ Hypoglycemic shock (insulin shock, wet shock, "diabetic shock”)—secondary to low blood sugar (<40 mg/dL). It may be a result of insulin overdose, a skipped meal, or strenuous exercise in a person with IDDM (insulindependent diabetes mellitus) or may be caused by an insulin-secreting pancreatic tumor.Symptoms are related to deficient sugar (fuel) in the brain. Treatment includes administration of sugar (glucose) and supporting blood pressure.

♦ Hypovolemic shock (hematogenic shock, hemorrhagic shock, oligemic shock)—most often a result of hemorrhage. The body has insufficient blood volume to maintain adequate cardiac output, blood pressure, and tissue perfusion (circulation). Oxygen is not delivered to tissues; wastes are not removed. Symptoms include physical collapse and prostration. This type of shock is discussed later in this topic:

♦ Irreversible shock—changes produced cannot be corrected by treatment; death is inevitable.

♦ Lung shock (shock lung, acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS])—pulmonary damage occurring early in shock. Symptoms include acute respiratory distress and pulmonary edema. Pulmonary vessels may plug with blood cells and platelets, leading to anoxia, damage to alveoli and capillaries, and generalized tissue hypoxia. Decreased surfactant (lubricating substance allowing lung expansion) may lead to atelectasis (collapsed lung).

♦ Neurogenic shock—vasodilation (blood vessel enlargement) secondary to cerebral trauma, spinal cord injury, very deep general or spinal anesthesia, or central nervous system (CNS) depression caused by toxins or drugs, such as “downers." The major mechanism is decreased peripheral vascular resistance.

♦ Septic shock (endotoxic shock, endotoxin shock, toxic shock)—results from overwhelming infection throughout the body, secondary to release of toxins, usually by gramnegative bacteria (particularly E. coli) and by cytokines.Viruses can also cause septic shock. Endotoxins, stimulated by infection, act on the vascular system, causing excess blood to be held in capillaries and veins and, therefore, to not be available to the general circulation; dangerous hypotension results. Other symptoms include chills, fever; warm and flushed skin, increased cardiac output, and less hypotension than in hypovolemic shock. If therapy is ineffective, symptoms will be similar to those of hypovolemic shock. Septic or toxic shock is one stage in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), most common in newborns or people over age 50, and in persons with diabetes, cirrhosis of the liver, or compromised immune systems (e.g., due to AIDS, cancer chemotherapy, bone marrow transplant).

♦ Toxic shock syndrome—shock caused by infection, usually by a staphylococcus organism (often associated with tampon use) can progress to untreatable (irreversible) shock. Bacteria produce a toxin that enters the bloodstream, causing a septic condition. Treatment involves removal of the tampon and antibiotic administration.

♦ Spinal shock—loss of spinal reflexes after acute transverse spinal cord injury. Flaccid paralysis below the level of injury and loss of reflexes and sensation occur. Arterial hypotension is possible.

♦ Traumatic shock—any shock caused by trauma, injury, or surgery, or heart damage following a myocardial infarction (MI); intestinal obstruction; perforation/rupture of viscera; strangulated hernia; or torsion of viscera (including ovary or testicle).

Less Commonly Known Types of Shock

♦ Anaphylactoid reaction—pseudoanaphylaxis (not true anaphylaxis)

♦ Anesthesia shock—from overdose of general anesthetic

♦ Burn shock—caused by loss of plasma

♦ Chronic shock—due to peripheral circulatory insufficiency in elders with debilitating diseases, or due to subnormal blood volume resulting from slow bleeding

♦ Cultural shock—distress related to assimilation into a new culture or country

♦ Distributive shock—marked decrease in peripheral vascular resistance, causing hypotension

♦ Epigastric shock—caused by a blow or extensive abdominal surgery

♦ Osmotic shock—rupture of plasma membrane/loss of cellular contents due to exposure to a hypotonic environment causing sudden change in intracellular osmotic pressure

♦ Pleural shock—hypotension secondary to thoracentesis (withdrawing excessive fluid from lung cavity). Symptoms include cyanosis (blueness of skin and mucous membranes), pallor (paleness), dilated pupils, and disturbances of pulse and respiration.

♦ Postoperative shock—shock occurring after surgery

♦ Protein shock—secondary to central arterial line protein administration

♦ Psychic (mental) shock—secondary to emotional stress, manifested by excessive fear, joy, anger, or grief

♦ Serum shock—anaphylactic shock secondary to administration of foreign serum to sensitized person

♦ Shell shock (battle fatigue)—mental disorder in World War I. Now known as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

♦ Surgical shock—occurring during/after surgery

♦ Testicular shock—results from sharp blow to testes

♦ Vasogenic shock—shock secondary to marked vasodilation (loss of vascular tone), usually resulting from damage to vasomotor centers in the brain stem or medulla

Hypovolemic Shock Sequel. Hypovolemic shock can lead to serious and life-threatening conditions such as metabolic acidosis (owing to increased lactic acid), or irreversible cerebral (brain), hepatic (liver), and renal (kidney) damage. A condition known as disseminated intravascular coagulation or DIC (widespread blood clots, mostly in the capillaries) can also occur and is very dangerous.

Shock is present in most serious injuries or illnesses, even though the classic signs may not be apparent. Compensatory action may keep a person responsive, and in some cases alert, even when massive blood loss has occurred. Look for signs of a change in the person’s level of consciousness.Progressive deterioration in LOC indicates that circulation to the brain is inadequate. Falling blood pressure is a late sign of shock. In extreme cases, military antishock trousers (MAST) are applied by paramedics. These are described and pictured later in this topic.

Treatment of Shock. Treatment of hypovolemic shock is symptomatic, aimed at correcting imbalances and removing the underlying cause of the shock. The treatment of most types of shock is approximately the same. In a first-aid situation:

• Efforts are made to increase the blood supply to the brain. In many cases, this involves elevating the feet or lowering the head.

• Bleeding sites are identified. If there is bleeding, the bleeding is controlled. Methods of controlling bleeding are discussed later in this topic.

Advanced procedures for treating shock include:

• Replacing fluid loss

• Administering blood and blood components

• Supporting blood pressure with medications, such as dopamine or norepinephrine

• Administering intravenous (IV) antibiotics, if the cause is an infection (after a culture and sensitivity test)

• Treating an infection: draining abscesses, debriding (removing necrosed, or dead, tissue), removing other possible sources of infection (e.g., catheters, IV, drainage tubes, tampons)

In all cases, the underlying causes of the shock are treated. In any emergency situation, if in doubt, treat for shock. In Practice: Nursing Care Guidelines 43-1 gives further pointers in the recognition and treatment of shock.

Key Concept Look for all signs of shock.

A falling blood pressure is a late sign of shock, and is ominous. Remember, shock is not always caused by blood loss.

ASSESSING THE PERSON IN AN EMERGENCY

The primary assessment is the assessment performed as soon as rescuers arrive at an emergency scene. During this assessment, life-threatening problems or injuries are identified and handled. If there are no life-threatening problems to correct, the primary assessment usually can be completed within 60 seconds.

IN PRACTICE: NURSING CARE GUIDELINES 43-1

TREATING SHOCK IN AN EMERGENCY

♦ Keep the person lying down and as calm as possible; reassure both the person and bystanders. Have someone call for assistance. Avoid rough handling of the injured person. Rationale: If the injured person becomes excited, the body’s oxygen needs will increase, thus increasing shock. The person may need advanced life support.

♦ Establish, maintain, and monitor airway breathing, and circulation. Rationale: These functions are vital to life.

♦ Administer a high concentration of oxygen, if available. Assist breathing as needed. Rationale: Administration of external oxygen increases the oxygen available in the blood and helps the person to breathe with less effort.

♦ Control bleeding. Rationale: Additional bleeding leads to more blood loss and adds to shock.

♦ Maintain body temperature; many people become chilled after an accident. Cover with a blanket or coats, if necessary Do not overheat the person. Rationale: The parasympathetic nervous system takes over in an emergency and reroutes blood to vital organs and away from the skin. Excessively low or high body temperature causes the heart to work harder.

♦ Try to put something under the person. Rationale: The ground is usually colder than the person; this will cause heat loss.

♦ Keep the person dry Rationale: If a person becomes wet, chilling occurs much more quickly.

♦ Give nothing by mouth. Rationale: The person could aspirate, choke, or vomit.

♦ Elevate the lower extremities, unless contraindicated. Rationale:

Elevating the legs helps blood to flow toward the brain where it is needed. Some people may need to have the head elevated, to breathe. In head injury, the body is kept level.

♦ Use the position most comfortable for the person that is within medical limits for the injury Rationale: Proper positioning maintains client comfort and prevents further injury.

♦ Immobilize fractures. Rationale: Immobilization prevents further injury.

♦ Monitor level of consciousness. Take and record vital signs at least every 5 minutes. Rationale: Level of consciousness and vital signs provide important information about the client’s status. Emergency and medical personnel must know the person’s reactions to the injury.

In many emergencies and injuries, the person must be treated for shock. Keep the person lying down. Maintain body temperature with blankets or coats. Elevate the feet and legs unless contraindicated.

The secondary assessment involves taking and recording the victim’s vital signs and continues with a head-to-toe assessment. This secondary assessment should take from 1 to 2 minutes, unless injuries requiring immediate intervention are identified. If the person has life-threatening problems, the secondary assessment may be delayed until the person is being transported. Keep in mind that the assessments of the nurse acting as a first-aid person can be performed only to the level of the individual nurse’s skills and training.

Whenever assessing a person in an emergency, use the acronym ABCDE to help you remember the order for assessment:

A = Airway and cervical spine B = Breathing

C = Circulation and bleeding D = Disability E = Expose and examine

A: Airway and Cervical Spine

Evaluate the airway to determine whether it is patent (open). While doing so, keep in mind the injury’s mechanism, location, and scope. The person must be able to breathe before other first-aid measures can be instituted.

If a possibility of spinal injury exists, stabilize the person’s cervical spine before attempting other activities. If the proper equipment is not available, wait for emergency rescue personnel to arrive. Unless there is an immediate danger, such as of explosion or fire, do not move the person!

B: Breathing

Assess breathing by listening for breath sounds, watching for chest movements, and feeling for breath against your cheek and ear.

Maintain the Airway. Maintain the person’s airway even if breathing is present. Blood, body fluids, and vomitus may accumulate in the person’s mouth and should be removed. Be sure the person’s tongue is out of the way; the tongue can occlude the airway in even a minor event, such as fainting. Position the person on the side if vomiting is imminent, while maintaining cervical spine alignment.

Nursing Alert The most common airway obstruction in an unconscious person is caused by the tongue falling back and occluding the airway

Observe Respirations. As you assess breathing, note if respirations appear to be of normal rate and depth.Examine the person’s mouth, gums, lips, and nail beds for color and moisture. Blueness (cyanosis) or duskiness in the skin, nail beds, or mucous membranes indicates a lack of oxygen.

Look for Life-Threatening Chest Injuries. If indicated by the injury’s mechanism, examine the person’s chest for life-threatening injuries. Chest injuries may cause internal bleeding and injury to the heart and lungs. If the body’s ability to exchange oxygen and circulate oxygenated blood diminishes, permanent brain damage or death will occur if left uncorrected. Immediately care for injuries such as rib fractures, punctured lung, stab wounds, gunshot wounds, compression injuries that result in a caved-in or open chest wall, and cardiac contusions.

Nursing Alert If the chest wall is not intact,plug the hole at once. This is an emergency life-threatening situation. If this is not done, the victim’s lungs will most likely collapse.

A serious situation is flail chest, which is a loss of chest wall stability. Flail chest is caused by several fractured ribs or detachment of the ribs from the sternum as a result of a crushing injury. The loose portion of the chest moves opposite its normal direction when the person breathes (paradoxical respiration). In other words, the chest rises on expiration and falls on inspiration. It is important to stabilize the chest wall as much as possible with whatever is available. For example, apply an all-cotton elastic (ACE) roller bandage and have the person lie on the affected side to apply pressure to the chest wall. Transport the person immediately.

Be alert for important signs of chest injuries, which include:

• Pain at the site of injury and on breathing

• Shortness of breath, gasping

• Failure of the chest to expand

• Coughing up blood

• Rapid, weak pulse and low blood pressure

• Cyanotic (bluish) lips, gums, fingernails, or fingertips

• Panic, agitation, nasal flaring

• Abnormal breathing sounds, such as wheezing or stridor

• Abnormal chest movements on breathing

C: Circulation and Bleeding

The heart must be pumping effectively for oxygen to be carried to the cells. There also must be sufficient blood volume to carry needed oxygen. Therefore, any disruption in the pumping action of the heart, blood pressure, or the amount of blood available can compromise the person’s condition.

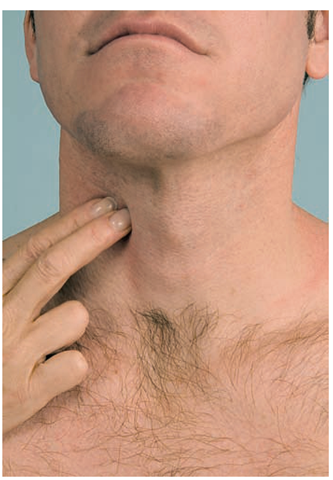

Palpate the Pulse. Palpate the victim’s pulse, using the carotid artery in the neck, for 5 to 10 seconds (Fig. 43-3). If no pulse is present, ask bystanders to call for assistance; this person needs advanced life support as soon as possible. Begin cardiac compressions immediately if qualified. (This technique should be learned in a special CPR course.)

Nursing Alert Do not reach across the person’s neck to feel the pulse. Feel it on the side nearest you. Rationale: Reaching across might accidentally cut off the airway.

FIGURE 43-3 · Palpating the carotid pulse on the same side as the rescuer.

Observe the Pulse. If a pulse is present, note its rate and regularity. Does it seem normal? Do not count the pulse at this time; just try to get a sense of its quality. While palpating the pulse, also observe skin color, temperature, and neck veins.

Reassess Breathing. A person may have a heartbeat without having respirations; therefore, reassess breathing. If the person is not breathing, begin rescue breathing immediately. (This technique is also learned in a special CPR course.)

Nursing Alert Use a one-way filtered breathing mask for CPR whenever possible, to protect the rescuer.

When the emergency medical services (EMS) personnel arrive, they can “bag” the person with an AMBU-bag (Fig. 43-4). This is a bag attached to a face mask that can be used to “breathe for” the person. This method is safer, more effective, and less tiring for the rescuer than rescue breathing. Supplemental oxygen can also be delivered via the AMBU-bag.

Assess for Progressing Shock. Always consider the possibility of shock in any injury. Use the capillary refill test to evaluate for shock, as follows:

• Press a finger into the middle of the person’s forehead until the spot being pressed turns white or a lighter color in a dark-skinned person.

• Remove the finger. Count the seconds it takes for color to return. (Count: one-one thousand; two-one thousand, and so on.)

• If it takes more than 2 seconds for color to return, shock is progressing (see discussion earlier in this topic on shock).

FIGURE 43-4 • The use of an AMBU-bag replaces mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Wear gloves whenever possible.

Assess and Control Hemorrhage. The presence of a palpable pulse indicates that the person’s heart is beating. However, you must also assess for major bleeding (hemorrhage).

Control hemorrhage immediately or the person will die from blood loss. With gloved hands, place sterile compresses over wounds and apply pressure. If blood seeps through the compresses, do not remove them, but place additional compresses over the top of those already in place. As necessary, apply additional pressure over the wound.

Key Concept Follow Standard Precautions whenever possible in administering first aid.

Measures that can be used to stop bleeding include:

• Apply direct pressure (should be done first).

• Elevate a bleeding limb.

• Apply an ice or cold pack, if available (CAUTION: place ice over several layers of dressings to avoid freezing body tissues).

• Apply indirect pressure: press the blood vessel at a pressure point against a bone (see Fig. 43-5 for an illustration of pressure points).

• If severe bleeding continues, reach into the wound and try to grasp the bleeding vessel with your fingers.

• If a woman has delivered a baby within the past few weeks, consider postpartum hemorrhage. This is most often caused by relaxation of the uterus (uterine atony). Immediate first aid is to have the woman empty her bladder and then to massage the uterus in an attempt to cause uterine contraction and stop the hemorrhage. Then, apply gentle, firm pressure to expel clots. She should consult her physician immediately.

• Apply a tourniquet as a last resort (see procedure later in this topic). Mark the tourniquet with the time it was applied. Also mark the client’s forehead, so all rescue workers know that a tourniquet is in place. Do not release a tourniquet after it is applied.

FIGURE 43-5 · Pressure points for hemorrhage control.

D: Disability

Neurologic Assessment. Conducting a neurologic assessment at an accident scene will help receiving medical personnel in the emergency room (ER). Identify levels of consciousness. The acronym AVPU will help in remembering these levels.

A = Alert: Speaks and moves spontaneously; answers questions about name, place, and date correctly V = Responsive to verbal stimuli only; answers when directly addressed P = Responsive to painful stimuli only (e.g., rubbing the sternum or pressure on the nail beds)

U = Unresponsive

Eye Signs. Assess the person’s pupillary responses. The pupils of both eyes should be the same (equal). They should be round and should constrict when a bright light quickly shines into them (react to light). The pupils should change size between close and far vision (accommodation). Reactions should be the same in both eyes, and they should move together when following a moving object (eyes coordinated). Remember this procedure by following PERRLA+C :

PE = Pupils Equal R = Round

RL = React to Light A = Accommodation OK C = Coordinated

E: Expose and Examine

Expose and examine any site of possible injury or any area that the person complains about, even if the area was examined previously. After having controlled the immediately life-threatening problems, obtain the person’s medical history, including any illnesses or allergies, if possible. Sources include the person, a MedicAlert tag, the family, or bystanders. Try to find out what happened.

If equipment is available, take vital signs (temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure) and ask about pain every 5 minutes after life-threatening problems are under control.Count pulse and respirations for at least 30 seconds. This recording establishes a baseline for further treatment. Report the findings to rescue personnel when they arrive.