Infectious and Inflammatory Heart Disorders

Chronic Rheumatic Heart Disease

Although adults may develop rheumatic fever, it is usually seen in children between the ages of 5 and 15 years.

Childhood rheumatic fever can result in heart valve malfunction. This chronic condition usually is not evident until about age 40. Symptoms include myocarditis (inflammation of the heart’s muscular walls), endocarditis (inflammation of the heart’s inner lining, usually involving the valves; discussed below), or pancarditis (inflammation of the entire heart).

The first signs include difficulty breathing, a cough, and sometimes cyanosis and expectoration (spitting) of blood. If the condition worsens, the client’s feet and ankles swell, the liver enlarges, and the abdominal cavity fills with fluid. Systolic blood pressure may fall. Such signs indicate heart failure.

The most common problem resulting from chronic rheumatic heart disease is a narrowing of the mitral valve, a condition called mitral stenosis. Because of this, blood collects in the chambers of the left side of the heart, enlarging them and leading to a backup of blood in the pulmonary vessels, which causes pulmonary edema. The left side of the heart is affected first. The condition progresses to the right side and leads to heart failure. Surgical replacement of a valve may be indicated. The physician determines the particular valve design that best fits the client’s needs.

To best protect against chronic rheumatic heart disease, a person who has had rheumatic fever should avoid exposure to colds, and streptococcal infections; keep up resistance; get adequate sleep; and eat a balanced diet. Complications may result from tooth extraction, oral surgery, or major surgery. Some clients take a daily maintenance dose of an antibiotic, such as penicillin G, as a prophylactic measure. Preventing streptococcal infections or recurrence of rheumatic fever is vital; each time a person has rheumatic fever, cardiac complications become more likely.

Bacterial Endocarditis

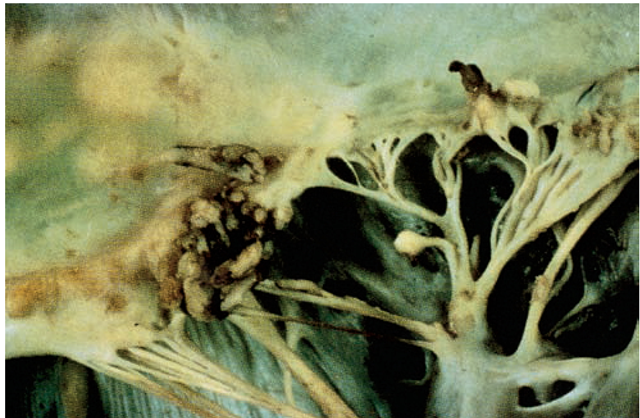

The membrane that lines the heart’s chambers and valves is called the endocardium. Infection of this membrane causes a condition known as endocarditis (Fig. 81-8).

FIGURE 81-8 · Bacterial endocarditis. The mitral valve shows destructive vegetations, which have eroded through the free margin of the valve leaflet.

Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE), a serious disease, was once nearly always fatal. Antibiotics have changed this outcome, but bacterial endocarditis is still a health problem. Modern treatment helps control it and prevents it from disabling affected individuals.

People with damaged heart valves, especially those who have had rheumatic fever or who have congenital heart defects, are most susceptible to SBE. Tooth extraction, childbirth, upper respiratory infections, or injecting street drugs directly into veins may release pathogens into the bloodstream that then attack damaged heart valves. Streptococci are frequent offenders.

One of the first signs of bacterial endocarditis is a low-grade fever that gradually increases. The person has chills, perspires, loses his or her appetite, and loses weight. The individual’s face may have a brownish tinge, and tiny reddish-purple spots (petechiae) appear on the skin and mucous membranes. Usually, the person is anemic (not enough oxygen is delivered to body tissues). As the disease progresses, signs of CHF appear.

The course of SBE is rapid and can be fatal if left untreated. However, 90% of cases can be cured without ill effects. Blood culture and sensitivity can usually identify the specific causative organism. Then, large doses of antibiotics to which the causative organism is sensitive are given.

Nursing Considerations. Make the person as comfortable as possible and instruct him or her to conserve energy. Frequently note the pulse rate and quality. Rationale: A change could indicate complications. Observe closely for fluctuation in body temperature and for any symptoms of complications. Rationale: Hematuria, pain, or impaired circulation in an extremity might result from a blood clot originating in the diseased valve.

Pericarditis

Pericarditis, an inflammation of the sac surrounding the heart, may be caused by infection, allergy, malignancy, trauma, or some other nonspecific problem. It is characterized by pain in the precordial area (over the heart and lower thorax), which is aggravated by breathing and twisting movements. A friction rub, a sign associated with pericarditis, is audible on auscultation. In most cases, pericardial infections are treated with antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents.

Coronary Artery Disease

People older than 65 years are the most common victims of CAD (also called ischemic heart disease), although the risk increases after age 40. During the early middle years, more men than women are affected. However, after menopause, women have an increased risk of two to three times that of men. Although a familial tendency toward the disease seems to exist, anyone can be affected. Therefore, all people should take precautions from an early age. In recent years, the healthcare community has given attention to preventing and discovering the disease early, before attacks occur and before atherosclerosis severely damages a person’s heart and blood vessels. In addition, health promotion and disease prevention activities have focused on measures to reduce the risk factors for developing CAD, which include:

• Smoking tobacco

• Increased levels of cholesterol and lipids in the bloodstream

• Physical inactivity and obesity

• Diabetes

Angina Pectoris

Literally translated, angina pectoris (usually referred to as angina) means “pain in the chest.” Angina occurs suddenly when extra exertion calls for the arteries to increase blood supply to the heart. Narrowed or obstructed arteries are unable to provide the necessary supply. Consequently, the heart muscle suffers.

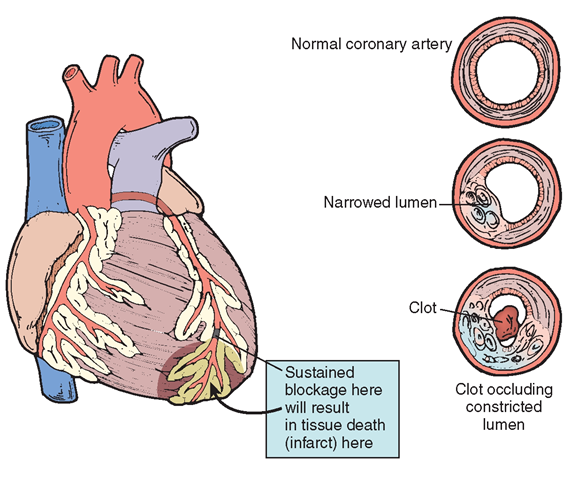

In angina, the blood vessels of the heart are unable to supply the heart muscle with adequate amounts of oxygen. If this loss of oxygen supply continues, the result is ischemia (prolonged deficiency of oxygenated blood) and necrosis of heart tissue, or MI. For example, a major factor associated with the vessels’ inability to supply adequate oxygen to the heart muscle is the development of plaques within the vessels, causing the vessels to narrow or become obstructed (Fig. 81-9).

When the underlying disease is coronary atherosclerosis, the prognosis may be more encouraging than when other factors are involved. The earlier the age of onset, the poorer the prognosis.

There are several types of angina pain. Intractable angina does not respond to therapy and often is so persistent that the person cannot work. Unstable angina is pain that increases and decreases in frequency, duration, and intensity. Nocturnal angina occurs at night. Decubitus angina occurs when the person is lying down and is relieved when the person sits up.

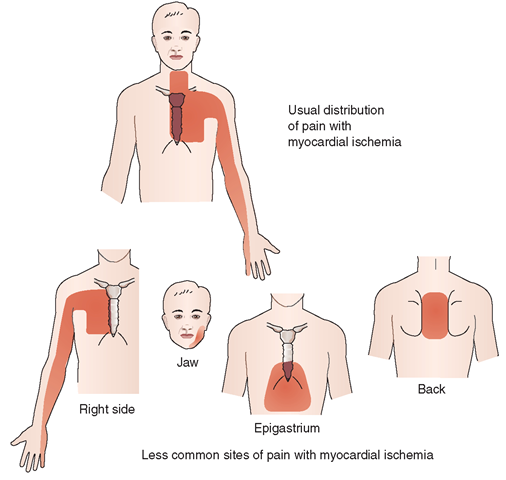

Signs and Symptoms. Pain is usually most severe over the chest, although it may spread to the shoulders, arms, neck, jaw, and back (Fig. 81-10).

The person often describes the sensation as tightening, viselike, or choking. Indigestion is often the first complaint. The person is more likely to feel pain in the left arm, because this is the direction of aortic branching. However, he or she may feel pain in either arm. The client may be pale, feel faint, or be dyspneic. Pain often stops in less than 5 minutes, but it is intense while it lasts. The pain is a warning signal that the heart is not getting enough blood and oxygen. People who ignore this warning are risking serious illness or sudden death if they do not immediately seek a physician’s care. The client may have recurrent angina attacks, but treatment lessens the danger of a fatal attack.

Diagnostic Tests. Diagnosis is made on the basis of ECG, specific blood tests (especially, cardiac isoenzymes), x-ray examinations, the client’s medical history, and specific symptoms. If nitroglycerin relieves the attack, it is considered angina. Exercise, exertion, eating, emotions, and exposure often precipitate angina. A person who has diabetes may not feel angina pain because of peripheral neuropathy.

Nursing Alert Angina pain that lasts for more than 15 minutes is considered an MI until proved otherwise. Repeated attacks of angina can be a sign of— or can contribute to—MI.

Medical and Surgical Treatment. Angina can be controlled with nitroglycerin tablets. As soon as an attack begins, the client places a tablet under the tongue, allowing it to dissolve. Nitroglycerin brings quick relief by dilating the coronary arteries; clients can use this drug safely for many years with no ill effects. Topical nitroglycerin ointment or nitroglycerin-impregnated transdermal pads are widely used to protect against anginal pain and promote its relief (see Table 81-1).

If medication fails to control the person’s anginal attacks, PTCA or coronary artery bypass surgery may be necessary.

Nursing Considerations. Help the client by teaching about angina pectoris and how to prevent further attacks (In Practice: Educating the Client 81-2). Clients who know that certain stresses bring on angina can learn measures to avoid these stresses or better cope with them. Clients with angina need to quit smoking because nicotine constricts the coronary arteries and increases blood pressure and pulse rate.

FIGURE 81-9 · Progression of atherosclerotic plaque in the blood vessels. Over time, the buildup of fat, cholesterol, fibrin, cellular waste products, and calcium on an artery’s endothelial lining may be complicated by hemorrhage, ulceration, calcification, or thrombosis. Infarction, stroke, or gangrene may also occur.

FIGURE 81-10 · Pain patterns with myocardial ischemia. The usual distribution of pain is referral to all or part of the sternal region, the left side of the chest, the neck, and down the ulnar side of the left forearm and hand. With severe ischemic pain, the right side of the chest and right arm are often involved as well, although isolated involvement of these areas is rare. Other sites sometimes involved, either alone or together with pain in other sites, are the jaw, epigastrium, and back.

Myocardial Infarction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) includes conditions such as an acute myocardial infarction (AMI), diagnostic ST changes on an ECG, and unstable angina. An MI, also known as heart attack, coronary thrombosis, or coronary occlusion, is the sudden blockage of one or more coronary arteries. If the blockage involves an extensive area, the person can die. If it involves a smaller area, necrosis of heart tissue and subsequent scarring will occur. However, other vessels can take over for the injured area (collateral circulation).

IN PRACTICE: EDUCATING THE CLIENT 81-2

TREATMENT OF ANGINA PECTORIS

♦ Use medications properly. Take them at the same time every day Do not stop or change dosages without a physician’s approval.

♦ Do not expose nitroglycerin to sunlight or moisture. Keep nitroglycerin in its original container. Purchase a fresh supply every 3 months.

♦ Check with your physician before taking any nonprescription medications. They may cause harmful side effects when combined with the cardiac medications.

♦ Make necessary lifestyle adjustments. Determine what you can and cannot do. Try to determine things that bring on attacks, so that you can curtail such activities.

♦ Stop smoking.

♦ Regular exercise and maintenance of an ideal weight help prevent the disease’s progression.

♦ Keep cholesterol within the 150 to 200 mg/dL range.

Complications can occur at any time after an acute MI. Complications primarily result from damage to the myocardium and its conduction system that occurred because of diminished coronary blood flow. The major complications of MI are life-threatening dysrhythmias and cardiac standstill. Abnormal heart rates and rhythms in the person with a recent MI often indicate that the left ventricle is pumping inadequately. As a result, CHF may occur.

Signs and Symptoms. Typically, but not in all cases, an MI begins suddenly, with sharp, severe chest pain that sometimes radiates to the left arm, shoulder, and back. Pain is similar to angina pain, but can last longer and is more severe; exertion is not always related to onset. Unlike angina, rest does not relieve the pain, and nitroglycerin does not help. Because an MI may imitate indigestion or a gallbladder attack with abdominal pain, definite diagnosis is often difficult.

Other common symptoms of MI include panic, restlessness, and confusion; a sense of impending death; ashen, cold, and clammy skin; dyspnea; cyanosis; rapid, thready, and irregular pulse; and drop in blood pressure and in body temperature. Nausea and vomiting may be present, and the person is often in shock. Silent attacks involving coronary artery disease (ones that show no symptoms) are common, especially among people with diabetes, and they may result in greater damage to the heart muscle. Denial occurs in many cases; the person cannot believe that he or she is having an MI. Family members may need to dial 911 for emergency medical services.

Nursing Alert The location and severity of pain caused by an MI can vary greatly Females, diabetics, and the elderly can present with symptoms, such as back pain, jaw pain, right arm pain, indigestion, nausea, fatigue, dyspnea, and even no pain. The severity of pain is not an accurate indicator of the severity of myocardial damage.

Diagnostic Tests. Tests help determine the nature of the MI. An ECG and several diagnostic blood tests are done to assess the duration and severity of the MI. Troponin levels rise. Troponin I is an accurate cardiac marker of cardiac injury. Other cardiac isoenzyme levels will also be elevated after an MI. These isoenzymes include fractional CK enzymes (specifically, CK-MB, a cardiac muscle-specific enzyme), lDh, and myoglobin. Serum myoglobin is tested to estimate the amount of damage to the heart muscle. Within 1 to 2 hours of an MI, serum myoglobin starts to rise, reaching a peak within 6 hours after the onset of symptoms. The sedimentation rate of the red blood cells is almost always higher after an MI, as is the AST level.

Nursing Alert When a nurse recognizes that an individual has risk factors for cardiovascular disease, preemptive, preventative teaching is important. Inform clients and their caregivers the importance of initiating emergency care before an MI or CVA occurs. Thrombolytic therapy to be most effective, must be started as soon as possible after the client develops symptoms.

Medical Treatment. Individuals complaining of chest pain should be evaluated promptly, with the goal of preventing further damage to the heart muscle. As previously discussed, thrombolytic therapy is an effective method of destroying the clot and preventing muscle damage, but it must be given in the very early phases of an MI. Pain indicates anoxia (lack of oxygen). Typically, morphine, administered IV, is the drug of choice for MI pain. Drugs also are given to dilate blood vessels, allowing more oxygen to reach heart muscle (see Table 81-1). Oxygen is administered by cannula or mask to assist with breathing and improve oxygenation, thereby relieving pain.

A low-cholesterol and restricted-sodium diet is usually ordered. Caffeine-containing beverages are usually not allowed. The client is informed of the hazards of smoking and is encouraged to quit as soon as possible.

Nursing Considerations. Immediately after diagnosis of an MI, continuous nursing care in the CCU is vital until the person’s condition stabilizes. During this acute phase, nursing care typically includes the following elements:

• Frequent vital signs

• Electronic cardiac monitoring

• Hemodynamic monitoring (electronic monitoring of internal cardiac pressures)

• I&O and daily weight Rationale: Lowered urinary output or sudden weight gain often is a sign of fluid retention or kidney disorders secondary to MI.

• Careful observation for restlessness, dyspnea, or chest pain Rationale: These signs indicate that tissue damage is worsening.

• Assessment for signs of CHF (e.g., dyspnea, frequent cough, crackles heard in the lung fields, and edema)

• Assessment of skin color Rationale: Pallor or cyanosis may indicate anoxia owing to impaired circulation.

• Medications to promote pain relief and improve the heart’s functioning

• Emotional support and stress reduction

• Monitoring of diet, IV fluids, or total parenteral nutrition (TPN)

During recovery from an MI, rest is a priority. Bed rest may be ordered up to approximately 72 hours after an MI, depending on the client’s overall condition. The ischemic areas may form necrotic tissue, which can take from 3 to 6 weeks to form scar tissue. Tough scar tissue forms after about 8 weeks. The size of the area of scar tissue is important because scar tissue will inhibit normal myocardial electrical conduction and it can inhibit normal contractions of the heart muscle. Cardiac dysrhythmias are possible owing to these factors. In Practice: Nursing Care Plan 81-1 highlights the nursing care associated with a priority nursing diagnosis.

• Allow clients who are able to use a commode at the bedside for a bowel movement. A commode is preferable to a bedpan. Rationale: Clients are more likely to strain on the bedpan, which could cause bradycardia owing to a vasovagal effect. Stool softeners are usually prescribed. Rationale: Stool softeners prevent straining.

• Assist the client with isometric (muscle-setting) exercises. Rationale: They provide muscle exercise without causing exhaustion. Incorporate a planned daily exercise program according to the cardiac rehabilitation program (Box 81-2).

• Use thromboembolic (antiembolism) stockings, as prescribed by the physician. Rationale: Proper use of stockings prevents thrombophlebitis (inflammation of the vein wall; discussed below).

• Place all necessary items within the client’s reach. Be sure the call light is available. Rationale: The client must not stretch or strain.

• Perform physical care (e.g., baths, backrubs). Rationale:

Provide rest and comfort.

BOX 81-2. Post-Myocardial Infarction Rehabilitation Plan

♦ In the healthcare facility, a gradual increase in the client’s activity level, as ordered by the physician

♦ Exercise tolerance test and exercise progression

♦ Graded exercise program with monitoring of tolerance based on blood pressure and pulse

♦ Emotional support and counseling

♦ Stress management

♦ Sexual counseling

♦ Lifestyle changes, as needed

♦ Risk factor management

♦ Dietary changes (e.g., low-fat diet for hyperlipidemia or weight control)

♦ Smoking cessation

♦ Hypertension control

♦ Medication and compliance, as ordered

IN PRACTICE :NURSING CARE PLAN 81-1

THE PERSON WITH AN ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION (MI)

Medical History: C.F., a 37-year-old single white male accountant, presented in the emergency department (ED) with crushing chest pain. Cardiac enzyme levels were obtained revealing a myocardial infarction (anterior wall of the left ventricle). He was admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU) approximately 18 hours ago. Oxygen at 4 L/minute via nasal cannula and intravenous morphine were ordered.

Medical Diagnosis: Acute MI of anterior wall of left ventricle

DATA COLLECTION/NURSING OBSERVATION

Client appears pale and slightly diaphoretic. Skin is cool and clammy. Vital signs were as follows: Temperature, 97.2°F (37.2°C); pulse, 120 beats/minute (bpm), irregular and thready; respirations, 26 breaths/minute; blood pressure (BP), 90/58 mm Hg. Intravenous (IV) morphine was given with relief; pain currently rated as 2 to 3 on a scale of 1 to 10. Client is currently resting in bed with head of bed elevated 45 degrees; oxygen being administered at 4L/minute. Oxygen saturation via pulse oximeter is at 96%. Continuous cardiac monitoring reveals frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) (>5/minute). Hemodynamic monitoring is in place. Urine output approximately 30 mL/hour (Although other nursing diagnoses may be appropriate, a priority nursing diagnosis is addressed below.)

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

Ineffective cardiopulmonary tissue perfusion related to effects of coronary artery disease and cardiac tissue damage secondary to acute MI as evidenced by low blood pressure, frequent PVCs (abnormal heart rhythm—more than 5/min), irregular thready pulse, and cool pale skin.

PLANNING

Short-term Goals

1. Within 24 hours, client will verbalize a decrease in complaints of pain.

2. Within 24 hours, client will exhibit pulse rate ranging between 60 and 100 bpm, BP within the range of 110 to 130 mm Hg/64 to 74 mm Hg, rare to absent PVCs, hourly urine output greater than 30 mL/hour; oxygen saturation of at least 97% with supplemental oxygen.

Long-term Goals

3. By 36 hours of admission, client will maintain vital signs and cardiac status within acceptable parameters.

4. Within 48 hours of admission, client will be transferred to cardiac nursing unit.

IMPLEMENTATION

Nursing Action

Assess for complaints of chest pain, using a pain rating scale. Rationale: Chest pain indicates myocardial ischemia. Using a pain rating scale aids in quantifying the client’s pain and provides a means for evaluating relief measures.

Nursing Action

Assess cardiopulmonary status. Monitor vital signs, especially pulse rate and blood pressure, at least hourly or more frequently if indicated, until stable. Assist with hemodynamic and continuous cardiac monitoring. Monitor respirations and oxygen saturation. Rationale: Frequent monitoring is essential to detect changes in the client’s condition as soon as possible.

Nursing Action

Assist with laboratory testing, such as cardiac enzyme levels, as necessary. Rationale: Cardiac enzyme levels are important indicators of MI and cardiac tissue damage.

EVALUATION

Client reports pain currently at 2 on a scale of 1 to 10 for the past 2 hours. Pulse rate of 106 bpm with slight irregularity noted; BP at 100/60 mm Hg; respirations 22 breaths/minute and regular; occasional PVCs noted, approximately 1 to 2 per minute. Urine output last hour was 40 mL. Oxygen saturation at 97% with 4 L of oxygen via nasal cannula. Lungs clear to auscultation. Progress to meeting Goals 1 and 2. Nursing Action

Administer morphine, as ordered, for complaints of pain. Monitor respiratory status closely after administration of morphine. Be prepared to administer other medications, including antianginal agents and vasodilators, as ordered. Rationale: Morphine is an effective analgesic for chest pain, but it is a central nervous system depressant that can cause respiratory depression. Other medications help to improve oxygen delivery to the heart muscle.

EVALUATION

Client states relief of chest pain for the past hour Pulse rate of 98 bpm and regular; BP 106/64 mm Hg; respirations at 22 breaths/minute. Oxygen saturation level at 98% with oxygen at 4 L/minute via nasal cannula. One to two PVCs noted in the last 30 minutes. Goal 1 met; progress to meeting Goal 2.

Nursing Action

Elevate head of bed to semi- to high-Fowler’s position. Encourage client to rest. Plan interactions so client has undisturbed periods of rest (1- to 2-hour intervals); keep environmental stress to a minimum. Rationale: Elevating the head of the bed eases the work of breathing. Planning for periods of undisturbed rest and minimizing stress reduces the workload of the heart, decreasing oxygen demand.

EVALUATION

Client reports no further episodes of chest pain. Pulse rate at 72 bpm and regular; BP 110/70 mm Hg. Skin is pale pink and warm. Continuous cardiac monitoring reveals no further evidence of PVCs. Urine output of 160 mL over past 3 hours. Oxygen saturation at 99% with oxygen at 4 L/minute. Goal 2 met.

Nursing Action

Gradually increase activity as ordered, getting client out of bed to chair or commode. Use cardiac monitoring tracings and oxygen saturation levels as guides. Rationale: Gradual increases in activity promote mobility without placing too great a demand on the heart. Cardiac monitoring and oxygen saturation levels provide evidence of client’s ability to tolerate increase in activity.

Evaluation: Client out of bed to chair for 15 minutes; vital signs, oxygen saturation level, and cardiac monitoring tracings within acceptable parameters. Progress to meeting Goals 3 and 4.

• After giving the bath and before making the bed, allow the client to rest for a while. Positioning in a semi-Fowler’s position is often preferred. Rationale: This position assists in breathing and relieves pain.

Clients who are admitted with a diagnosis of “rule out MI,” typically written as “R/O MI,” are placed on complete bed rest until it is determined whether they have had a heart attack. Those who have no pain may feed themselves, even in the acute phase. Plan activities to promote maximum relaxation and to reduce stress.

Clients who have had an MI can live a normal life and, generally, can return to previous employment, depending on the extent of myocardial damage. The goal is not to change a client’s lifestyle completely, but to have the client make necessary modifications to prevent recurrences. Before discharge, instruct clients and their families about patterns of healthy living and how to recognize emotional and physical stress. If the client is taking antihypertensive drugs, emphasize the necessity of taking prescribed medications despite that he or she feels well. Discuss potential side effects when teaching. Also, include teaching about signs and symptoms that require immediate medical help (see In Practice: Educating the Client 81-3). Carefully and completely document this teaching.