Fat-Soluble Vitamins

Fat-soluble vitamins (see Table 30-7) are absorbed into the lymphatic circulation with fat and must attach to a protein carrier to be transported through the blood. The body stores fat-soluble vitamins primarily in the liver and in fat tissue.

IN PRACTICE: EDUCATING THE CLIENT 30-1

VITAMINS

Encourage people who take vitamin supplements to consider the following:

• Freshness: Vitamin pills can lose their potency over time, especially when stored in a bathroom medicine cabinet. Look for pills with an expiration date on the label. Do not use after the expired date.

• Price: In most cases, cost has little to do with vitamin quality

• Supplements should provide no more than 100% Daily Value, because more is not necessarily better and in some instances is toxic.

• Supplements should contain no unnecessary ingredients. The average diet supplies enough biotin, pantothenic acid, phosphorus, iodine, and chloride. Trace minerals, such as nickel, silicon, and zinc may be unnecessary. Sugar in vitamins is safe because the small amount contained within a vitamin pill is not harmful.

Because they are stored, deficiency symptoms are slow to develop. Vitamins A and D are toxic when consumed in excess of need over a prolonged period. Cooking does not easily destroy fat-soluble vitamins.

Vitamin A. Retinol or vitamin A is a group of related substances that promote growth, sustain normal vision, support normal reproduction, and maintain healthy skin and mucous membranes (thereby increasing the body’s resistance to infection). Preformed vitamin A is found only in animal sources, such as liver, butter, and egg yolk; fortified milk is also a good source. Carotene is a precursor of vitamin A; that is, the body converts carotene to vitamin A, but not quickly enough to be toxic. Excellent food sources of carotene are deep orange and deep green fruits and vegetables, such as sweet potatoes, winter squash, carrots, broccoli, spinach, green leafy vegetables, and cantaloupe.

Vitamin D. Calciferol or vitamin D is a group of sterols essential in regulating the body’s use of calcium and phosphorus. A marked deficiency of vitamin D hampers growth and affects bone hardness. This deficiency causes a childhood condition known as rickets, in which the bones do not harden as they should, but instead bend into deformed positions, such as bowlegs. Pregnant and lactating women must provide themselves with sufficient vitamin D to prevent rickets from developing in the child and to preserve their own bones and teeth. Sunlight on the skin plays a role in the conversion of vitamin D to its active form, as does the functioning of the liver and kidneys. The best food sources of vitamin D are fish liver oils and fortified milk.

Groups at the highest risk for vitamin D deficiency are totally breast-fed infants, vegetarians who consume no dairy products and people who get little sunshine (e.g., institutionalized or homebound individuals). Secondary vitamin D deficiency can occur in people with liver disease, kidney disease, or fat malabsorption syndromes. Because excess vitamin D is toxic, vitamin D should be supplemented only with physician approval.

Vitamin E. Alpha-tocopherol or vitamin E is sometimes called the “reproductive vitamin” or the “antisterility vitamin” because it was originally found to be a necessary component for reproduction in animals. However, no evidence supports the concept that vitamin E has an effect on human reproduction or sexual function. Although the role of vitamin E is not fully understood, it has been proven to be a powerful antioxidant. In this role, it protects vitamins A and C, as well as some fatty acids and phospholipids in the cell membrane, from destruction by oxidation. Vitamin E deficiency is rare, except in malabsorption disorders, such as cystic fibrosis and pancreatic disorders. Vitamin E is found in plant fat and vegetable oils, products made with vegetable oils (e.g., margarine and shortening), wheat germ, nuts, and green leafy vegetables.

Vitamin K. Menadione or vitamin K is essential in the formation of prothrombin and at least five other proteins that are required for the clotting of blood. Because vitamin K is found in a variety of foods, the average diet supplies an adequate amount. Good sources are liver, egg yolk, cauliflower, cabbage, spinach, and other green leafy vegetables. Intestinal bacteria synthesize vitamin K in insufficient quantities to meet the total vitamin K requirement. The limited amount the body stores is found in the liver. A dietary deficiency is unlikely. Intake of foods that contain high amounts of vitamin K should be monitored when taking anticoagulants, such as warfarin (Coumadin), because vitamin K can interfere with the effectiveness of warfarin. Some clients’ diets may routinely contain these vegetables, therefore, the dosage of warfarin needs to be adjusted to include the routine intake of these vitamin K-rich foods. Signs of hemorrhaging may be due to a vitamin K deficiency, which is treated in adults with either oral or intramuscular administration of vitamin K.

Water-Soluble Vitamins

Water-soluble vitamins (see Table 30-8) include vitamins C and B complex. They are absorbed directly through the intestinal walls into the bloodstream. They are also easily absorbed and excreted in urine when consumed in excess. Water-soluble vitamins are considered nontoxic because the body generally does not store them. Deficiencies develop more quickly with them than with fat-soluble vitamins because water-soluble vitamins are not readily stored and are excreted rapidly. Food, light, heat, acids, and alkaline solutions can easily destroy water-soluble vitamins.

Vitamin C. Vitamin C is probably equally well known by its chemical name, ascorbic acid. Over the years, experts have recognized its many functions but continue to discover further uses. One of the functions of vitamin C in vital body processes is to aid in the formation of collagen, the most important protein in connective tissue. By holding cells together, collagen contributes to healthy tissue and to the proper functioning of blood vessels, skin, gums, bones, joints, and muscles—essentially, all body tissues and organs. Vitamin C is also involved in reactions involving numerous other compounds, such as folic acid, histamine, neurotransmitters, bile acids, leukocytes, and corticosteroids. Vitamin C enhances the absorption of the form of iron that is predominate in plants, and is an effective antioxidant. Individuals who have had surgery or who have suffered extensive burns frequently receive large supplemental doses of ascorbic acid; it is essential to wound healing.

The classic disease of vitamin C deficiency, scurvy, is rare in the United States. Symptoms of scurvy include bleeding gums, loose teeth, sore and stiff joints, tiny hemorrhages, and great weight loss. Lesser vitamin C deficiencies affect health by causing listlessness, irritability, and lowered resistance to disease.

Vitamin C is probably the most unstable of all the vitamins. Exposure to air, drying, heating, and storing destroy it. As an acid, it survives longer in acidic surroundings; therefore, baking soda (the alkali, sodium bicarbonate) should not be added to food sources of vitamin C during cooking. Tomatoes retain vitamin C better than other vegetables because they contain acid. Freezing fruits and vegetables helps to preserve their vitamin C content, but they should be used immediately after thawing. Carefully canned fruits and vegetables also retain this vitamin because air is excluded during the canning process.

Because vitamin C is destroyed by heat and is water soluble, cooking should be done in as little water as possible, and overcooking should be avoided. Many raw fruits and vegetables, especially citrus fruits, are high in vitamin C. For instance, one cup of orange juice provides more than the RDA for vitamin C. Research has yet to confirm Linus Pauling’s theory that vitamin C can prevent or cure the common cold. Because of its antioxidant properties, vitamin C may play an important role in cancer prevention. However, some studies have shown that mega-doses of vitamin C may increase the resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapy treatment. Doses greater than the DRI may increase the risk of kidney stones in some people.

Populations at risk for vitamin C deficiency include people who do not eat fruits and vegetables, alcoholics, and people of low socioeconomic status. Smokers require extra vitamin C because nicotine inhibits its absorption.

Vitamin B Complex. The B complex vitamins are generally known as thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, folate or folic acid, cobalamin, pyridoxine, biotin, and pantothenic acid. Most B complex vitamins have numbers such as B1, B12, and so on. However, the trend is to identify the vitamin by its proper name instead of a number (see Table 30-8).

The following B complex vitamins are all widely distributed in foods. Although each one is chemically distinct, they share many similar functions, dietary sources, and deficiency symptoms.

Thiamine (B1): Thiamine promotes general body efficiency. It plays a role in growth, cell metabolism, appetite, neurologic functioning, RNA and DNA formation, and normal muscle tone in cardiac and digestive tissues. As part of a coenzyme, thiamine is essential for the metabolism of carbohydrate and certain amino acids. Signs of a deficiency of thiamine are poor appetite, fatigue, irritability, general lethargy, nausea, vomiting, loss of weight and strength, depression, mental confusion, and poor intestinal tone. A severe deficiency causes beriberi, a disease of the nervous system that leads to paralysis and death from heart failure.

The best food sources of thiamine are pork, whole-grain and enriched breads and cereals, legumes, peas, organ meats, and dried yeast. The body does not store thiamine to any great extent. Thiamine is lost during cooking, especially when cooking is prolonged or at high temperatures. Alkalis also destroy thiamine. In the United States, thiamine deficiency occurs most frequently in persons who abuse alcohol because they “waste” thiamine in the metabolism of alcohol. A thiamine supplement is usually prescribed for these clients.

Riboflavin (B2): Riboflavin functions primarily as a component of two coenzymes that catalyze many reactions, including the metabolism of carbohydrate, fat, and protein. It is essential for growth. Riboflavin deficiency is rare in the United States; people at the greatest risk for deficiency are those who take in large amounts of alcohol, older adults, people on low-calorie diets, and people with malabsorption syndromes. Signs of a riboflavin deficiency include cheilosis (cracking and sores at the corners of the mouth), glossitis (inflammation of the tongue, with a smooth texture and purplish-red color), and stomatitis (inflammation of the lining of the mouth). The body does not store riboflavin to any extent; therefore, a person’s diet must provide a steady supply.

Riboflavin is available in a wide variety of foods but only in small quantities. The best sources are milk and milk products, meat, poultry, fish, and whole-grain or enriched breads and cereals. Exposure of riboflavin to light while in solution destroys it.

Niacin (B3): Niacin exists as nicotinic acid and nicotin -amide. It plays a vital role in the release of energy from carbohydrate, fat, and protein. It is also needed for the production of fatty acids, cholesterol, and steroid hormones.

The best sources of niacin are lean meat, liver, kidney, yeast, peanut butter, whole-grain and enriched products, and dried peas and beans. Niacin is not readily destroyed by heat, light, acids, or alkalis. The body stores only a small amount of niacin.

A marked niacin deficiency leads to the disease pellagra. The mucous membranes of the mouth and digestive tract become red and inflamed, and lesions appear on the skin. Symptoms of severe deficiency progress through the four Ds: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and death. Niacin deficiency is rare, except in persons who abuse alcohol. Physicians sometimes prescribe nicotinic acid in gram quantities to help lower blood cholesterol levels; however, side effects are common. These possible side effects include flushing of the skin, hot flashes, headache, hypotension, tachycardia, hypoglycemia, and liver damage.

Folate/folic acid (B9): Folate is the group name for this B complex vitamin. Folate plays a major role in the synthesis of DNA and RNA and in the formation of red and white blood cells. Folic acid is the form of folate used in vitamin supplements. It is also involved in the synthesis of certain enzymes and in amino acid metabolism. Folate is available in many foods. Excellent sources include enriched cereals, liver, organ meats, milk, eggs, asparagus, broccoli, green leafy vegetables, dried peas and beans, and orange juice. Cereals and breads are now required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be fortified with folic acid.

Deficiency results in megaloblastic (macrocytic) anemia, glossitis, diarrhea, poor growth, impaired nerve function, and increased risk of heart attack. Intake of high amounts of folate masks vitamin B12 deficiency (pernicious anemia), which, when left untreated, can cause irreversible neurologic damage or death. Folic acid deficiency is common in all parts of the world. In the United States, folic acid deficiency is most common among older adults, pregnant women, alcoholics, fad dieters, and women taking oral contraceptives. A folate supplement is usually prescribed for these individuals. New research has proved that folate, given before conception and during early pregnancy, helps prevent neural tube defects, such as spina bifida.

Cobalamin (B12): Cobalamin is a family of compounds, all of which contain cobalt. It is important in folate metabolism and in blood cell formation. It is also involved in maintaining the myelin sheath covering certain nerves. Cobalamin and folate are needed to activate each other.

For the intestine to absorb vitamin B12, intrinsic factor must be present. Intrinsic factor is a protein-containing compound the stomach produces in the presence of hydrochloric acid. Conditions that impair the secretion of intrinsic factor, such as gastric surgery or gastric cancer, cause B12 malabsorption and pernicious anemia, an anemia characterized by abnormal RBCs known as mega-loblasts. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the United States is due to impaired absorption, not an inadequate dietary intake.

Vitamin B12 deficiency leads to anemia, neurologic symptoms, increased risk of heart attack, and other generalized symptoms. Because the body stores vitamin B12, it may take years for symptoms to develop.

Vitamin B12 is found exclusively in animal sources; therefore, pure vegetarians who consume no animal products are at risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. Bacteria in the small intestine may produce small amounts of absorbable vitamin B12.

Pyridoxine (B6): Vitamin B6 is a family of compounds: pyridoxal, pyridoxine, and pyridoxamine. The official name is pyridoxine, but it is commonly interchanged with the more common term vitamin B6. Pyridoxine is needed for enzyme activity in the metabolism of protein, carbohydrate, and fat. It is especially important in protein metabolism. Other functions include forming heme for hemoglobin, metabolizing neurotransmitters, synthesizing myelin sheaths, and maintaining cellular immunity.

Rich sources of pyridoxine (B6) are meat, fish, poultry, and eggs. Whole-wheat products, nuts, and oats are also good sources. Most diets contain adequate amounts of this vitamin.

A deficiency of vitamin B6 is most likely to occur secondary to malabsorption syndromes, alcoholism, or certain drug therapies and is most likely to develop in people with multiple B vitamin deficiencies. Symptoms may include retarded growth, confusion, headaches, and seizures. A deficiency of pyridoxine may also increase the risk of heart attack. Large quantities of vitamin B6 taken for months or years can cause neurologic problems, such as difficulty walking, numbness of the feet and hands, clumsiness, and nerve degeneration. Symptoms gradually improve after the vitamin is discontinued.

Biotin: Biotin (rarely seen as vitamin H) is essential in the functioning of many enzymes. It acts as a coenzyme in the metabolism of carbohydrate and fat and aids in the removal of certain nitrogen groups from amino acids.

Biotin is found in almost all foods. Liver, egg yolks, soy flour, cereals, and yeast are the best sources of biotin.

Biotin deficiency is rare except when a person consumes large amounts of raw egg whites. A substance in the egg white, avidin, binds biotin and keeps it from being absorbed.

Pantothenic acid: Pantothenic acid is involved in a number of metabolic processes in humans, especially in the metabolism of protein, carbohydrates, and fats. Because of its central role in energy metabolism, it is vital to all energy-requiring body processes. The average diet supplies a sufficient amount; no RDA has been established. The word pantothenic means “widespread,” and pantothenic acid is found in many foods. Good sources include liver, organ meats, egg yolk, dried peas and beans, broccoli, whole grains, lean meats, and poultry.

Prebiotics and Probiotics

Based on emerging science, prebiotics and probiotics can benefit both the well and the ailing patient. Prebiotics are nondigestible food ingredients that selectively feed probiotic bacteria. Probiotics, on the other hand, are healthy live bacteria. Together, prebiotics and probiotics work to maintain a healthy digestive system and may boost immune function. Both prebiotics and probiotics are also available in supplement form.

Probiotics may be found in some whole foods and specialized food products. The biggest category of foods in the United States that contains live and active cultures is fermented dairy products, such as kefir, yogurt, and cheeses. Specialized food products containing probiotics are increasingly found on store shelves. Currently, the major group of prebiotics in use in the United States food supply is the fructans, which are discussed in the carbohydrate section.

Resistant starch is another category of prebiotics that are found naturally in raw potatoes and unripe fruit, such as bananas. Commonly manufactured for use by the food industry, it may be difficult to recognize on food labels, therefore, look for claims on the label such as high fiber, reduced-energy, or reduced-carbohydrate.

A HEALTHY DIET

A healthy diet is one that provides an adequate amount of each essential nutrient needed to support growth and development, perform physical activity, and maintain health. In addition to meeting physiologic requirements, diet is also used to satisfy a variety of personal, social, and cultural needs. These factors must be considered in diet planning. The diets of all individuals must consist of foods that are easily attainable and affordable. People can use an infinite variety and combination of foods to form a healthy diet. The current philosophy is that no good foods or bad foods exist, and that all foods can be enjoyed in moderation.

Although ensuring that the diet provides sufficient nutrients is important, of greater concern for most Americans today is avoiding dietary excesses, particularly of calories, fat, cholesterol, and sodium, which are associated with the development of several chronic diseases. Many Americans can achieve risk reduction by implementing dietary and lifestyle changes.

How can you choose a diet that provides sufficient amounts of essential nutrients but not excessive amounts of others, and help your clients do the same? Where is the line between adequate nutrition and “over”-nutrition? As a nurse, you are often in a position to promote wellness by counseling clients and their families on the “why” and “how to” of food choices. Today’s most important nutritional concepts are variety, moderation, and balance.

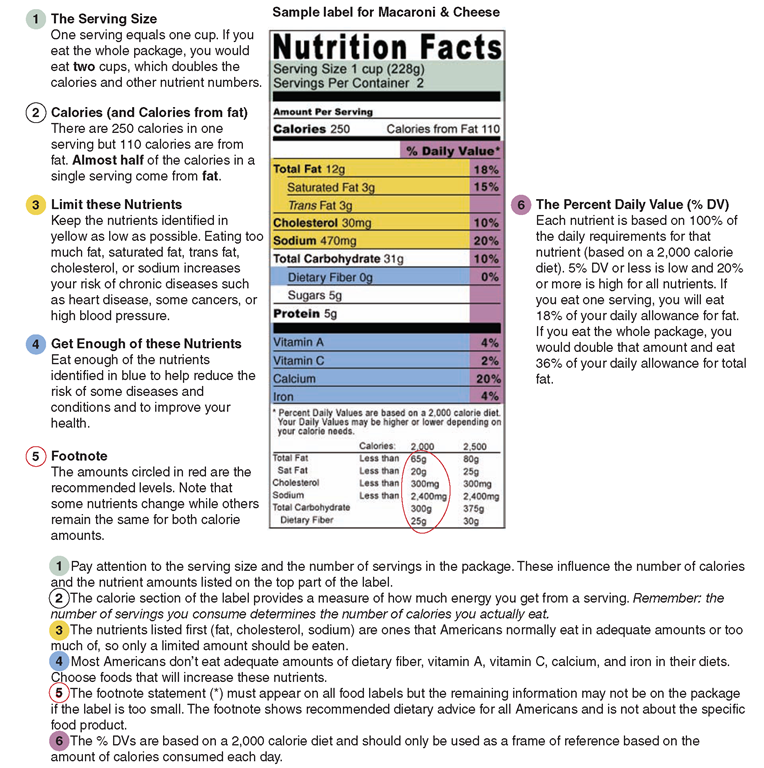

The Nutrition Facts Label

The Nutrition Facts Label provides product-specific information, such as serving size, calories, and nutrient information. On larger packages, a footnote is included that contains Daily Values (DVs) for 2,000- and 2,500-calorie diets. The footnote also contains recommended dietary information for important nutrients, including fats, sodium, and fiber. Figure 30-3 illustrates the Nutrition Facts Label and shows the individual how to use its references.

The nurse can use the information on the Nutrition Facts Label to help the client understand nutrient content and to control the intake of specific nutrients, such as the various types of fats or the amount of sugar in a product. This label provides useful information for the client with certain heart diseases, diabetes, and other disorders.

The Nutrition Facts Label lists nutrients per serving of the following:

• Calories

• Total fat

• Saturated fat

• Cholesterol

• Sodium

• Total carbohydrate

• Fiber

Ingredients are listed in descending order by weight on the Nutrition Facts Label; that is, the first ingredient listed makes up the largest proportion of the food. Also be aware that some ingredients are listed separately, especially sugars, which may mean that the total content of sugar is higher than it appears. If sugars are listed separately, the label can appear to state that sugar is not the majority ingredient. See Box 30-1 for a list of commonly used sugar ingredients.

On the ingredient list, also look for foods to avoid, such as coconut oil or palm oil, which are high in unhealthy saturated fat. Avoid foods that are hydrogenated, which are high in trans fat. Healthy ingredients would include soy and monounsaturated fats, such as olive, canola, or peanut oils, or whole grains, such as whole-wheat flour and oats. Foods high in fiber are recommended. These include dried beans, fruits, vegetables, and grains.

Diet Planning

In the hospital or other healthcare facility, a dietitian will most likely plan menus. As a nurse, you will need to understand dietary requirements to teach clients effectively. Emphasize foods with nutrient density (i.e., foods that provide significant amounts of key nutrients per volume consumed). Nutrient density, as well as caloric density, becomes increasingly important for those with diminished appetites owing to nausea, pain, inactivity, boredom, or anxiety. For instance, hospitalized individuals often have increased protein requirements to promote healing. However, for the protein to be used for healing and not for energy, adequate calories need to be consumed. Encouraging clients with high protein requirements to consume the higher calorie foods on their tray first, such as meat and milk, can aid their healing process.

FIGURE 30-3 · The Nutrition Facts Label. (United States Food and Drug Administration, 2004).

At the same time, keeping meals interesting is important. Food and mealtimes take on much greater significance in a healthcare setting and are often the highlight of the client’s day. Food is also one area of care over which clients can “vent” their frustrations and feelings of helplessness. So, although nutrient density is important from a medical standpoint, eating less nutritious foods may sometimes be important on an emotional level.

Nutritional Problems

The nutritional problems of most Americans are not caused by deficiencies of single nutrients, but to overconsumption of nutrients. It is well documented that of the leading causes of death, four are associated with dietary excesses and imbalances:

• Coronary artery disease

• Certain types of cancer

• Cerebral vascular accident (stroke)

• Diabetes mellitus

Overnutrition also contributes to such conditions as hypertension, osteoporosis, dental caries (decay), gastrointestinal diseases, and obesity. Although no one can say for certain exactly what proportion of these disorders is caused by diet, evidence suggests that a diet high in calories, fat (especially saturated fat), cholesterol, and sodium, but low in complex carbohydrates and fiber, contributes significantly to the high rates of chronic diseases among many North Americans.

Health and Body Weight

Body Weight Assessment. In the past, Ideal Body Weight (IBW) was used to describe optimal weight for optimal health. Newer standards for weight replace “ideal” with “healthy” because “ideal” is difficult to define.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is used more frequently than IBW. BMI measures weight in relation to height. Defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, BMI allows comparison of weights among people of differing heights. BMI nomograms (graphs) have eliminated the need to perform calculations and these are readily available on the Internet. The classification “obese BMI” is generally 30 to 40, with very obese BMI considered to be >40. Clients in these BMI categories may be more susceptible to numerous physical disorders. Bariatric (weight loss) surgery may be considered.

Also consider the concept that some people may be above their “healthy weight” according to their BMI, but not be “overweight.” Neither IBW nor BMI takes into account the body composition of people who are muscular (e.g., athletes) or who have greater bone density and therefore may weigh more than their “healthy weight.”

Overweight and Obesity. The percentage of Americans who fall into the “overweight” and “obese” categories has increased dramatically over the past few decades and is now considered to be at epidemic levels. Overweight individuals are individuals who weigh 10% to 20% more than the “ideal” weight per height. Obesity refers to an excessive amount of fat on the body. Adolescent obesity is of special concern because these individuals are much more likely to develop lifelong complications such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease at a relatively younger age. Overweight or obese people do not necessarily consume adequate amounts of all nutrients, although they tend to consume more calories than are needed for metabolism.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition literally means “bad nutrition.” Too much or too little of one or more nutrients may cause poor nutrition; however, malnutrition most commonly refers to undernutrition. Inadequate food intake may cause malnutrition, or it may occur secondary to alterations in digestion, absorption, or metabolism of nutrients.

Although certain population groups are at risk for vitamin and mineral deficiencies (e.g., alcoholics, adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, people of low socioeconomic status, and people with certain chronic diseases), severe deficiencies are rare in the United States. The prevalence of mild deficiencies, which may not produce obvious physical symptoms but can be detected through blood analysis, varies among nutrients. Ironically, hospitalized clients are at risk for protein-calorie malnutrition (PCM), which is seen in diets that are low in calories and protein. Clients with PCM, which is often unrecognized and not diagnosed, have prolonged hospitalizations. They do not heal well because there is not enough protein to make or repair new tissue, and they have a lowered resistance to infection.

Two other types of protein deficiencies are identified but not commonly found in the United States or Canada: marasmus and kwashiorkor. Marasmus is extreme malnutrition and emaciation that occurs chiefly in young children as a result of inadequate calories and proteins. It may be seen in starvation or in the child with failure to thrive.The child has progressive wasting of subcutaneous tissue and muscle. Slow and gradual addition of foods and maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance are keys to survival and growth.

Kwashiorkor is also a form of severe malnutrition found primarily in children; it is caused by severe protein deficiencies. Typically, the child with kwashiorkor has access to some calories and does not lose weight as drastically as does the child with marasmus (who has an inadequate intake of protein and an inadequate amount of calories). Kwashiorkor commonly occurs as a child is weaned from the breast because a new sibling has been born. The infant receives the mother’s breast milk, while the older child receives some nutrients and calories from the food sources available, but does not receive adequate proteins. Eventually, the malnourished child experiences mental and physical retardation, dermatoses, necrosis, and fibroses. The child may also experience nervous system irritability, edema, anemia, and fatty degeneration of the liver, often visualized as an edematous or distended abdomen, which is a result of liver necrosis and ascites. Mental retardation is permanent, but with adequate nutritional interventions, physical growth can resume. Box 30-5 summarizes major dietary guidelines and key recommendations for the general population.