Schultz, Dutch (b. Aug. 6, 1902; d. Oct. 24, 1935). Gangster. Dutch Schultz’s real name was Arthur Flegenheimer. He grew up in the Bronx, where his reputation for toughness earned him the nickname Dutch Schultz after a legendary neighborhood gang leader. By the time he was thirty, Schultz had become a major figure in New York City bootlegging, the numbers racket, and corrupt labor unions—an empire tied together by his willingness to inflict pain and death on those who stood in his way. When the authorities in New York bore down on Schultz, he switched his base of operations to Newark.

On the evening of October 23, 1935, the gangster and three members of his mob were eating dinner and discussing their plans in the Palace Chop House on East Park Street in downtown Newark, when two gunmen burst through the door and began shooting. Police called to the scene found that Schultz and his men had all been shot and that the gunmen had escaped. The four wounded men were taken by ambulance to Newark City Hospital, where one by one they died, with Schultz passing away at 8:35 p.m. the next evening. After the Saint Valentine’s Day massacre in Chicago, it was the largest gangland killing of that era.

The two hit men were later apprehended. One died in the electric chair, and the other served twenty-three years in New Jersey prisons. It has been theorized that they acted on the orders of organized crime leaders who wanted Schultz removed.

The legend of the Dutchman oulived him. Before he died, Schultz began speaking in a feverish delerium, and police stationed a stenographer at his bedside to take down his words in case they might constitute evidence. The transcript contains strange phrases like "a boy has never wept, nor dashed a thousand kim.” This stream-of-consciousness prose appealed to the avant-garde. The writer William S. Burroughs did an experimental work entitled The Last Words of Dutch Schultz. The character of Dutch Schultz has appeared in Hollywood movies, on television, and in fiction. In these works his violent death has often been depicted as taking place in New York City.

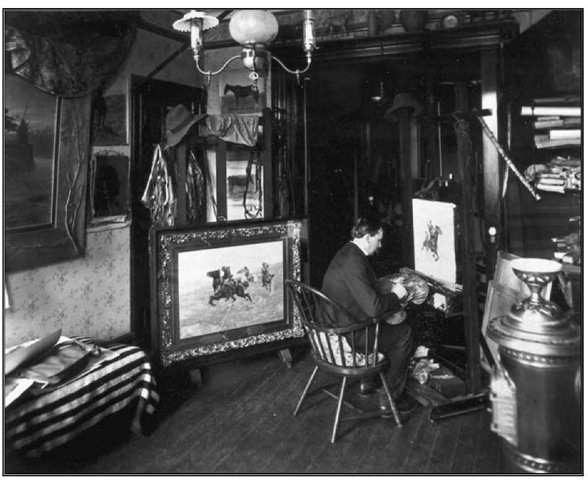

Charles Schreyvogel in his Hoboken studio c. 1899.

Schuyler-Hamilton House. Dr.Jabez Campfield, Revolutionary War surgeon and New Jersey militia officer, bought this house in Morristown in 1765. During the winter of 1779-1780, Dr. Campfield and his wife hosted Dr. John Cochrane, chief physician and surgeon of the Continental Army, and his wife, the sister of Gen. Philip Schuyler of Albany, New York. It was in the Campfield house that Dr. Cochrane’s wife’s niece, Elizabeth Schuyler, was courted by Alexander Hamilton, who was billeted at the nearby Ford Mansion, which served as Gen. George Washington’s headquarters. Campfield’s house was purchased and restored in 1923 by the Morristown chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, who renamed it the Schuyler-Hamilton House and use it as their chapter house and museum.

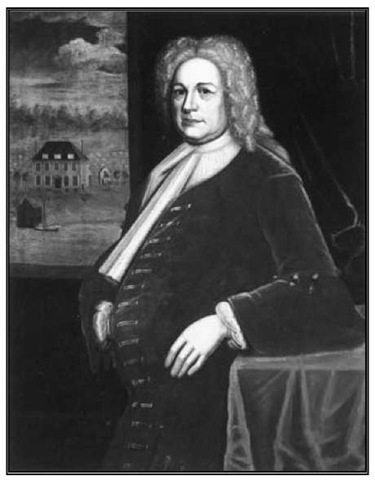

John Watson (attributed), Arent Schuyler, n.d. Oil on canvas, 50 3/3 x 41 in.

Schuyler Mine. Around 1712 Arent Schuyler, son of a wealthy Albany, New York, family, established one of the earliest colonial copper-mining operations on the western fringe of the Hackensack Meadows. Situated four miles northeast of present-day Newark’s Broad and Market streets, the mine, also known as the Arlington, Belleville, or Victoria mine, was operated by Schuyler’s slaves until the arrival in the 1750s of experienced Welsh and Cornish miners. Under the management of one of these immigrants, Josiah Hornblower, the Schuyler Mine began using steam engines to pump water from deep mine shafts. Extracted ore was ferried across the Hudson River to New York and then shipped to Holland or, after the enforcement of British colonial policies, directly to England.

Although idled during the Revolutionary era by accidental fire damage and war, by the 1790s the mine was once again supplying ore to a set of shops and foundries established by new investors. It was here in the 1790s that the first steam engine was manufactured in the United States. Yet the amount of copper ore extracted from the site—never enormous— was greatly depleted by the nineteenth century. Various manufacturing concerns continued to remove what little ore remained up until 1901, when the mine closed permanently.

Schwarzkopf, H. Norman (b. Aug. 28,1895; d. Nov. 25, 1958). Soldier and State Police superintendent. Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf was born in Newark and later resided in Lawrenceville and West Orange. A graduate of West Point and veteran of World War I, he was appointed as the first colonel and superintendent of the New Jersey State Police in July 1921. During his tenure as superintendent he directed the investigation of the Lindbergh kidnapping that took place in 1932 and testified at the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann. After serving three terms as superintendent, he left the State Police in 1936 and became an executive with the Middlesex Transport Company and also narrated the weekly radio program Gang Busters. Schwarzkopf reenlisted in the military and served in Europe during World War II and in Iran, where he organized the Imperial Iranian Gendarmerie. In 1951 he returned to state service as the administrative director of the Department of Law and Public Safety and was responsible for coordinating and supervising all law enforcement activities for the department. He died at home on November 25,1958.

Col. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, the first superintendent of the New Jersey State Police, 1928.

Science and technology. The history of science and technology in New Jersey has been greatly influenced by the nature of the state’s geography and geology. The effort to understand and exploit the state’s natural resources dominated much of the early scientific work that took place in New Jersey, and these resources were extremely important in determining the kinds of technology and industry that took root in the state. New Jersey’s position on the Atlantic seaboard, poised between two of the nation’s principal cities, proved equally important as an influence.

The Lenape, the Native Americans who populated the region, were skilled farmers and transmitted knowledge of indigenous plants to the European settlers. In time, the fertility of the soil and the ready markets of the nation would earn New Jersey the nickname "The Garden State.” The notion of the garden state was enhanced in the 1890s when Peter Hendersen, considered by his contemporaries to be "the father of horticulture and ornamental gardening” in the United States, industrialized horticulture, building huge, technologically sophisticated greenhouses. By 1890 he had five acres covered by glass and was producing seeds and plants for suburban gardens. Commercial farming has long been significant in New Jersey, which remains an important producer of fresh market produce. New Jersey’s role in food preservation, an important industry in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, has also been significant. Beginning in the 1840s, southern New Jersey was an early center of canning, and in the 1890s the Campbell Soup Company of Camden grew on the basis of Dr. John T. Dorrance’s invention of condensed soup. Forty years later, the frozenfood industry got its start at Seabrook Farms.

Though agriculture has given the state its nickname, New Jersey is best known as an industrial state. The rivers and streams in the northern part of the state are well suited to water power, and the first important industrial technology introduced into New Jersey was the watermill, which served a variety of industrial and agricultural purposes. The first new national technological enterprise in New Jersey was the Paterson mills, built in the 1790s in accordance with the vision of Alexander Hamilton’s Society for Establishment of Useful Manufactures, to take advantage of the seventy-seven-foot Great Falls of the Passaic River. Newark drew on the power and water supplied by the river to become an important industrial center. By the eve of the Civil War, Newark had a larger percentage of its population engaged in manufacturing (73.5 percent) than any other city in the nation. Its most important nineteenth-century industry was shoemaking, which was advanced by Seth Boyden’s 1818 invention of patent leather; by i860 Newark manufactured 90 percent of America’s patent leather. A wide variety of other crafts and industries could be found in Newark and in other nearby cities. Of particular note was the extensive manufacturing enterprise of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, which became the worldwide leader in the industry. Clothing and apparel manufacture were particularly important through much of New Jersey’s history.

During the nineteenth century the most important technological enterprise in the state was the iron industry. Although the native inhabitants knew of iron deposits, they seem not to have used the metal themselves. However, iron was a mainstay of European culture, and colonists had built ironworks in the new land as soon as they could. New Jersey, with iron deposits near the surface, had its first forge in i674 at Tinton Falls (Monmouth County). Iron mining in the Jersey Highlands began shortly after the turn of the eighteenth century and became a major industry within fifty years. However, its success led to deforestation, and by the early nineteenth century the forges were starved for fuel. The Morris Canal brought anthracite coal and an iron-mining revival that lasted through most of the century. Miners worked bog-iron deposits in the Pine Barrens, especially after Highland iron production declined in the early nineteenth century, but the arrival of anthracite as fuel doomed the southern mines. Particularly important in the development of the state’s iron industry was Seth Boyden’s process for making malleable iron, which he developed in Newark in i826. Twenty-two years later he also devised a process for zinc smelting that put New Jersey at the fore of the zinc industry for the rest of the century.

Transportation was vital to American industrialization, and the nineteenth century saw the construction of huge transportation projects, notably canals and railroads. The Morris Canal, built to connect the New York metropolitan area with the northern Delaware River, was a marvel not just for its size but for the way boats were cranked up inclined planes to scale the northwestern heights of the state. One of the most important early iron enterprises in northern New Jersey was the Speedwell Iron Works founded by Stephen Vail near Morristown, which contributed to the development of steamship technology. It was also here that Vail’s son Alfred assisted Samuel Morse in developing the electric telegraph in 1837-1838. A major use of iron in the nineteenth century was for railroads. This spurred the establishment by Peter Cooper and Abram Hewitt of the Trenton Iron Works in 1845, which remained the industry leader in America until the 1880s. Their success was instrumental in John Roebling’s decision to open his wire-rope works in Trenton a few years later. Roebling’s innovations lay behind the nation’s great suspension bridges as well as the elevators that made skyscrapers possible. The Stevens family—Colonel John and his sons Robert and Edwin—were in the vanguard of inventors and promoters of steam railroads. They imported the famous ten-ton English locomotive John Bull for their venture. Among their many innovations, Robert devised the T-rail design still in use, the spike to hold it, the plates and rivets to join it, and the use of wooden ties with crushed stone for a roadbed. The Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken was founded in 1870 by a bequest in the will of Edwin A. Stevens.

Science and technology came to prominence in New Jersey’s higher education during the mid-nineteenth century with Joseph Henry’s tenure at Princeton University, where he was a professor of physics before becoming secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. George H. Cook, a professor of chemistry at Rutgers College, conducted a geological survey of the state. He was subsequently instrumental in Rutgers’s acquisition of federal Morrill Act land-grant funds, and the Rutgers Scientific School was founded in 1864.

Scientific agriculture was centered at Rutgers, especially in the agricultural experiment station established in 1880, with George Cook as its first director. Under Jacob Lipman, the school investigated soil microbiology in the early twentieth century. Selman Waksman, discoverer of streptomycin and other antibiotics (a word he coined), followed Lipman as director. Royalties from Waksman’s antibiotics patents enabled Rutgers to establish the Waksman Institute of Microbiology. Waksman’s work and the work of the Institute bolstered the pharmaceutical industry, already well established in the state.

Apart from these examples, little significant research took place at New Jersey’s institutions of higher learning in the nineteenth century. Instead, the most important research centers in the state were Thomas Edison’s research and development laboratories in Menlo Park (1876) and West Orange (1887), which produced many key inventions in sound recording, telephony, and electric light and power, as well as the first motion picture camera and innovations in cement manufacture and battery technology. Edison helped to change invention into industrial research with these laboratories, which were better equipped than any possessed by his contemporaries, including those available to the American scientific community. Edison’s laboratory became a model for others in the electrical industry, including Newark electrical instrument manufacturer Edward Weston. Edison’s success also helped lay the groundwork for modern industrial research and development by showing how invention itself could be an industrial process and that corporate support for it could produce large benefits. Edison’s laboratories became models for the early research organizations established at corporations such as Bell Telephone and General Electric, which in turn forged a new style of science-based industrial research during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Bell Laboratories, which helped to establish a new model for industrial research, dominated advances in telecommunications technology during the second half of the twentieth century. The first laboratory established by the Bell Telephone Company in Boston drew on Edison’s model, but by the 1920s, first in New York and then later in New Jersey, AT&T created a new type of industrial research laboratory in which basic scientific research became the foundation of new communications technology. One consequence of this is that eleven researchers at the laboratory have shared in six Nobel Prizes in physics ranging from the transistor to radio astronomy. Bell scientists and engineers have also been responsible for some of the key innovations in modern communications and electronics, including transistors, lasers, digital transmission and switching, cellular telephone technology, digital signal processing, and the Unix operating system.

These contributions are part of a long history of New Jersey innovations in communication. First, Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail invented the instruments and code for telegraphic transmission at Speedwell. Then, at his Newark shops, Thomas Edison developed several telegraph innovations, most notably improved stock tickers and the quadruplex telegraph, which enabled four messages to be sent simultaneously on a single wire. After moving to Menlo Park in 1876, Edison developed the transmitter that made the telephone a practical instrument, while at the same time producing the phonograph, and he also developed the first practical system of incandescent light and power. Later, at his West Orange laboratory he developed improved technology that was crucial to the commercial success of the sound recording industry. His principal rival in the 1890s and early twentieth century was the Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, maker of the first commercial disk records. American motion pictures also began at Edison’s West Orange laboratory in the mid-i890s. While radio did not originate in New Jersey, it has been an important center in the development of the industry. Guglielmo Marconi transmitted his first news reports from New Jersey, and the first transatlantic transmission originated in the state as well. David Sarnoff founded the RCA laboratories near Princeton, which played a crucial role in electronics research, including the development of early television and color television, liquid crystal displays (LCDs), and electron microscopy.

Pharmaceutical innovation has been the other key product of New Jersey industrial research in the twentieth century. Although a significant pharmaceutical industry emerged in New Jersey in the late nineteenth century, science-based research was very limited until the i930s. The first significant laboratory was probably the one established by Squibb in i9i2 in New Brunswick, which expanded significantly during World War I. Another early laboratory was the Takamine Laboratory in Clifton. The development of antibiotics in the late i930s and early i940s, including Selman Waksman’s work at Rutgers, spurred the industry to establish modern research laboratories, with Merck and Squibb leading the way. Today, most of the major pharmaceutical companies are based in New Jersey or have a strong presence in the state, which remains a leading center of pharmaceutical research and manufacturing.

While industrial rather than university research has been a dominant feature of New Jersey history, the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton emerged as an important center during the i930s. While maintaining close ties to Princeton University, the Institute has its own faculty, which have included such notable European emigre scientists as Albert Einstein, Kurt Godel, and John von Neumann. Especially in its early years the Institute was an important center for research in mathematics, physics, and computing.

Although Princeton University and Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, have become significant research universities, it is in the field of industrial research that New Jersey has excelled. The state remains today a center of innovation, with the highest concentration of scientists in the nation and a ranking of fourth among states in the amount of money spent on research and development. The Garden State has become the Innovation State.

Scotch Plains. 9.06-square-mile township in Union County. First settled by Scots in the 1660s, the village of "Scotsplain” grew beside the Green Brook near the gap in the First Watchung Mountain. The agricultural village was centered on the intersection of the trail from Piscataway and the road "from Rahway to the mountain.” Stagecoaches began making stops at the crossroads Stage House Inn in 1769. Farming and mills contributed to the economic well-being of the community through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. Located in the "West Fields” of Elizabethtown until 1794, the settlement was part of Westfield Township until 1877, when Fanwood Township was separated from it. Fanwood Borough split off from the township in 1895. The municipality officially took the name of the Township of Scotch Plains in 1917. Post-World War II housing demands significantly impacted the community and open farmland was developed into housing, causing the population to double between 1950 and i960. The community remains largely residential and single-family homes predominate.

In 2000, the population of 22,732 was 79 percent white, ii percent black, and 7 percent Asian. The median household income in 2000 was $81,599.