Save Barnegat Bay. Founded in 1971,Save Barnegat Bay is a not-for-profit environmental group that works to conserve undeveloped natural land and protect water quality throughout the Barnegat Bay watershed. It is a local chapter of the Izaak Walton League of America, a national organization whose major goals are the protection and sustainable use of natural resources and the guarantee of a high quality of life for people of all generations. Save Barnegat Bay’s efforts to protect natural land take two basic forms: first, scrutinizing development proposals on the local and state level; and second, working with local, state, and national organizations and governmental agencies to purchase environmentally sensitive land in order to convey it to public ownership as permanently protected natural open space with public access provided.

Sayre and Fisher Brick Company.Established around 1850 by Joseph R. Sayre, Jr., and Peter Fisher in a village then known as Wood’s Landing, the Sayre and Fisher Company became in time one of the country’s leading manufacturers of fire brick, enamel brick, and ordinary building brick. In 1876 the region was renamed Sayreville, after the company’s cofounder, and incorporated as an independent township in Middlesex County. The brickworks, which provided employment for a large proportion of area residents, also included a power plant, a granary, a bakery, a slaughterhouse, a coal yard, an ice plant, a general store, a machine shop, and a blacksmith shop, as well as company housing. By 1905 Sayre and Fisher, which had acquired a number of neighboring brick making factories, was operating a facility extending two miles along the Raritan River. It included thirteen separate yards with a production capacity of 18 million bricks per year; by 1912 production capacity had increased to 62 million bricks per year. Brick manufacturing suffered a marked decline in the 1930s, then rebounded as the country pulled out of the Depression and remained profitable through the 1960s, when another downturn hit the industry. The Sayre and Fisher plant finally closed in 1970. While the industrial buildings were razed, remnants of the area’s brick making past still remain, including some brick dwellings, formerly company housing; a water tower; and the Sayre and Fisher Reading Room, a brick edifice constructed in 1883 for company recreational use and for showcasing the firm’s ornamental products.

Sayreville. 36-square-mile borough in Middlesex County. The borough of Sayreville is situated on the south bank of the Raritan River connected by three bridges to the north bank of the river. Originally part of South Amboy, Sayreville started life as a township around 1876 and became a borough in 1920. The area was noted for its fertile farms and its fine fishing. The Sayre and Fisher Brickworks, now defunct, was its principal industry.

Large industries located in Sayreville included Hercules Powder and DuPont. During World War I munitions makers came to the Parlin and Morgan sections of Sayreville to set up plants. On October 5, 1918, blasts at the T. A. Gillespie shell-loading plant lasted fourteen hours, terrified people for thirty miles, broke local windows, killed 100 people, and cost $25 million. Even in 2000, the Army Corps of Engineers continues digging remnants of the blast from the soil in Sayreville; some believe the explosions were an act of sabotage.

Sayreville has grown from a small blue-collar town to a large blue- and white-collar borough in the last twenty years. The 2000 population of 40,377 was 76 percent white, 11 percent Asian, and 9 percent black. The median household income in 2000 was $58,919.

Schering-Plough Corporation.First established in the United States in 1876 to distribute the pharmaceutical products of Schering AG, a German firm, Schering was dissolved during World War I. The company reestablished itself in New York City in 1928, incorporated in Madison, New Jersey, in 1935, and became a leader in the synthesis of steroid drugs. Schering was nationalized by the U.S. government during World War II and never returned to affiliation with Schering AG. The popular antihistamine Chlor-Trimeton, introduced shortly after the war, enhanced Schering’s profits. In 1952, a group headed by Merrill Lynch acquired Schering, which increased its financial success with the 1955 release of two new corticosteroids, Meti-corten (prednisone) and Meticortelone. In 1966 Schering introduced the antibiotic Garamycin (gentamicin).

Abe Plough began his career in the early 1900s in Memphis, Tennessee, as a peddler of home-manufactured cure-alls. With the purchase of the St. Joseph Company of Chattanooga in 1920, Plough brought children’s aspirin into his inventory. In the 1950s, well before the widespread promulgation of safety regulations, Plough required childproof caps placed on his product.

In 1971 Plough, Inc., merged with Schering, bringing DiGel, Coppertone sun care products, and the Maybelline cosmetics line into the Schering-Plough Corporation. The new company acquired Scholl, Inc., manufacturers of Dr. Scholl’s foot-care products. Other well-received over-the-counter Schering-Plough products include a number of cold, flu, sinus, and allergy medications, such as Afrin, Co-ricidin, and Drixoral. Most of the company’s sales come from prescription pharmaceuticals such as the Claritin (loratadine) antihis-tamine line, Proventil (albuterol) for asthma, and the anticancer/antiviral drug Intron A (interferon alfa-2b, recombinant), used in the treatment of various diseases including malignant melanoma and hairy cell leukemia.

Starting in 1980, Schering-Plough made an increasing commitment to biotechnological research, acquiring a share in Biogen, a Swiss firm. The company later bought two California biotechnology companies, DNAX Research Institute and Canji. In 1993 Schering-Plough built a new research facility in Ke-nilworth, also the location of the company’s worldwide headquarters.

Schirra, Walter Marty, Jr. (b. Mar.12,1923). Astronaut. Wally Schirra was born in Hackensack and attended junior high school in Oradell and Dwight Morrow High School in Englewood, where he was an outstanding student and athlete. He studied for a year at Newark College of Engineering and graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1945. Schirra flew ninety combat missions during the Korean War and shot down two MiG fighter jets. His father had been a fighter pilot in World War I, his mother a stunt aviator.

After his combat service Schirra became a navy test pilot and helped develop the Sidewinder missile before becoming one of America’s seven original astronauts in 1959 and laying the foundation for the historic Moon landing a decade later. He rocketed into space in 1962, orbited the Earth again in 1965, and three years later became the only one of the original group to fly in all three pioneering programs—Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. He produced the first U.S. telecast from space, took part in the initial rendezvous of two spacecraft, and was command pilot for the eleven-day Apollo 7 mission that cleared a path for the Moon flight of 1969.

Schirra founded a consulting company in 1979 in California, where he and his wife, the former Josephine Cook Fraser, reside. They were married in 1946.

Schnitzler, William F. (b. Jan. 21, 1904; d. June 17, 1983). Labor leader. William F. Schnitzler was born in Newark, and his first job was working on a peddler’s wagon. During World War I he worked in an ammunition factory before becoming a metal polisher during the 1920s. When that firm closed, he became an apprentice baker with the Peerless Baking Company of Newark, where he joined Local 84 of the Baker and Confectionery Workers International Union of America.

Schnitzler was elected the union business agent in 1943 and general secretary-treasurer in 1946. In 1950, he replaced retiring president Herman Winter as head of the union and was elected to a full five-year term the next year. He succeeded George Meany as secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) when Meany became president of that organization in 1952. Schnitzler was a prominent member of the committee that negotiated the merger of the AFL and the CIO in 1955. He chaired a committee organized in 1961 to investigate discrimination against minorities in unions and promised to "bust” racial discrimination. In 1969, Schnitzler retired from the AFL-CIO. He was living in Lewes, Delaware, at the time of his death in 1983.

School desegregation. According to the National Center of Education Statistics, New Jersey’s schools are among the most segregated in the nation. As of school year 1998-1999, 51.3 percent of black students and 40.7 percent of Latino students attended schools that were 90 percent minority. Only Michigan, Illinois, and New York had higher percentages for black students and New York, Texas, and California for Hispanic students.

These attendance disparities do not necessarily result from intentional school segregation. Rather, they result from racial disparity in the state’s residential living patterns. Further, many of the state’s more than six hundred school districts are small, and the relatively modest-sized districts tend to be substantially white or black. The school districts reflect the disparate racial living patterns of their communities. As a result, while the state’s population as a whole grows more diverse, its pattern of school attendance reflects racial separation.

Such segregated patterns, as exist in New Jersey, have been termed de facto segregation, that is, segregation that results from geographical conditions rather than legal intention. The state does, however, have a history of de jure, or legalized, segregation, notwithstanding an 1881 statute that prohibited excluding children from any public school on the grounds of race. For example, an 1884 case involved the city of Burlington, which at that time operated four public schools, one of which was designated for "colored” children only and the others exclusively for white children. It was acknowledged at the state’s 1947 constitutional convention that in southern New Jersey, some of which lies below the latitude of the Mason-Dixon line, legalized school segregation existed through the 1940s.

The 1947 constitution, which contains strong ant segregation language, and the school laws reflect a policy that has been interpreted by state courts to go beyond those required by the federal Constitution. Thus, in a few situations, state courts have ordered desegregation remedies that would not have been required under federal constitutional law. Most remarkably, the state supreme court in 1971 ordered regionalization of the Morristown and Morris Township school districts in order to avoid racial concentration in the Morristown schools. The case arose when Morris Township sought to withdraw its students from Morristown High School and form its own high school, which would have been predominately white.

However, the Morristown case has proved unique. In other situations involving withdrawal from sending-receiving relationships, such as the Englewood-Englewood Cliffs case decided in 2002 by the state supreme court, the court has sought other remedies, such as magnet schools, rather than ordering region-alization.

Further, in the absence of any sending and receiving relationship between communities, regional school attendance disparities based on racial housing patterns have prevailed. Neither the state’s substantial efforts to equalize school funding through the Abbott v. Burke line of decisions nor its efforts to promote affordable housing opportunities in suburban jurisdictions through the Mount Laurel cases have yet resulted in the amelioration of patterns of school segregation.

The state has made efforts to integrate individual school districts. Through the year 2000, approximately sixty districts had desegregation orders based on racial imbalances— again going beyond what the United States Supreme Court would require—in place. However, because the racial composition of many communities is predominantly of one race or the other, even these state initiatives have not significantly altered patterns of racial disparity throughout the state.

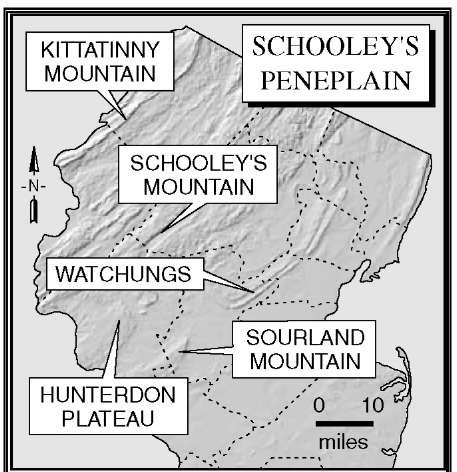

Schooley’s peneplain. A peneplain is a land surface of slight relief that occurs in the late stages of landmass denudation, following millions of years of erosional activity. The plateau-like summits of Schooley’s Mountain, Kittatinny Mountain, the Hunterdon Plateau, the Watchungs, Sourland Mountain, and the Palisades represent remnants of an ancient landscape that has since become eroded. The largest remnant of this nearly horizontal summit level is on top of Schooley’s Mountain in northwestern New Jersey; the surface is called Schooley’s peneplain. This cycle of peneplana-tionwas developed onanolder erosionsurface called the Fall Zone peneplain.

School funding. The funding of public education in New Jersey has a long and controversial history. The state was slow to establish a source of funds to educate its children, not providing real state responsibility and aid until the 1870s. Then it provided for the "thorough and efficient” education of children between "the ages of five and eighteen” in free public schools. The same wording was later included in the 1947 state constitution. Most of the money for education, however, came from local real estate taxes, and went to the many school districts in the state (there are currently 611 districts). While it was long clear that this led to increasing differences in funding between wealthy (often suburban) and poor (largely urban) districts, little was done to rectify the situation until the 1970s. At that time, the New Jersey State Supreme Court, in Robinson v. Cahill (1973), ruled that near total reliance on property taxes was both unconstitutional and unfair because it ended up being unequal. After the court insisted on change, the legislature in 1976 enacted a gross income tax so that the state could increase its contribution to the costs of local public schools and reduce the disparities in resources available to finance education among local school districts. The result was an increase in state contributions to education, but not the elimination of all differences between wealthy and poor districts. These remaining differences reflect regional costs of living, community preferences, efficiency in services, and quality of education as well as variation in the available tax base. The state supreme court, ina series of Abbott case decisions from 1985 to the present, has repeatedly returned to the issue of an educational funding that is neither "thorough and efficient” nor equal, without totally resolving it.

Since the 1970s, school funding has also been impacted by new state laws requiring funding for special education, bilingual education, vocational education, at-risk pupils, transportation, and teacher retirement (pensions), in addition to basic instruction. Also in the recent Abbott decisions the court has extended the age of children covered by the "thorough and efficient” definition to three-and four-year-olds in disadvantaged (poorer) Abbott districts.

By 2000 New Jersey schools were funded by local taxes (55 percent), state aid (40 percent), and federal aid (5 percent). Total state aid in 2001 was $6.8 billion for basic education, with total funds for local education coming to nearly one-third of the state’s budget. Despite the increase in state spending since the 1970s, school spending is by far the largest component of local property taxes, and New Jersey still depends more on property taxes than other states. In 2001, $15 billion was spent to educate the approximately 1.3 million public school pupils in New Jersey, with per pupil spending the highest in the nation but varying between districts. At the same time, while the state has very poor districts (Camden is ranked as the fifth poorest city in the country with 37 percent of its population living in poverty), according to the 2000 census New Jersey is the wealthiest state in the nation. The state has yet to come up with a perfect plan for school funding that reconciles all of its differences with the needs of the children in its public schools.

School laws. Responding to the increase in the size and diversity of New Jersey’s school-age population, the legislature in 1881 passed several school laws that changed aspects of the state’s existing ways of funding its educational system. Legislation adopted in that year enabled towns to raise funds for school costs not covered by the state school tax, and ensured that state school funds were to be used exclusively for educational purposes. The laws also provided state funding for teacher education institutions, a state vocational school for girls, and a state reform school. Cities were authorized to borrow money to cover teacher salaries. State matching funds were provided for the establishment of vocational schools. Perhaps the most important legislation in 1881 was a law sponsored by Sen. James C. Youngblood of Morristown to end the exclusion of children from public schools because of religion, nationality, or color. This law resulted in the desegregation of schools in the northern counties of the state. The law did not prohibit the establishment of separate schools, however, which enabled segregation to continue in the southern part of the state. Many members of the black community in South Jersey felt that the establishment of separate schools was preferable to having their children attend integrated schools where they would encounter hostility.

Schooner. A schooner is a type of fore-and-aft rigged sailing vessel. The sails are supported at the top edge by a spar known as the gaff and usually along their lower edge by a spar called the boom. Gaff and boom are attached to the masts at their ends so that at rest they are parallel to the hull’s center-line. The forward end of the gaff is lower than the rear so the sail’s leading and tailing edges are parallel but the top and bottom edges are not. Schooners had between two and seven masts although were rarely built with more than four. There are many variations on this basic sail plan. Hulls differed with use: deeper for the open ocean, shallower with flatter bottoms for inshore work, and scow-shaped for rivers and bays. The schooner’s sail plan made it highly maneuverable so that it was principally used as a coastal freight carrier or fishing vessel. Few were transoceanic transports, although many operated in the Caribbean.

Before 1720,90 percent of all vessels built in New Jersey were single-masted sloops. The schooner became more popular with demands for greater capacity. During the 1800s almost all New Jersey schooners had two masts. Data on northern New Jersey schooners show that they ranged from 50 to 100 feet long and 130 to 200 tons burden. They usually had six-man crews. Shipyards along Dennis Creek in Cape May County built many large schooners in the 1800s and early 1900s, while schooners with up to five masts were built on the Maurice River.

There were two schooner types unique to New Jersey: the periagua and the Delaware Bay dredgeboat. The periagua appeared in the New York Harbor region in the mid-i700s and had disappeared by the mid-i800s. It used a modified cat rig (no sails carried ahead of the forward mast), flat-bottomed usually scow-shaped hulls, and leeboards instead of a deep keel. In the i700s, periaguas were about 30 feet long; by the mid-i800s some were up to 75 feet long. Built between i875 and i929, over five hundred Delaware Bay dredgeboats were used in the oyster fishery. The largest was i02 feet long, although most were 70 to 80 feet long. The Delaware Bay boats differ from similar vessels on the Chesapeake by their deeper hulls—better suited to less sheltered water. A topmast and triangular topsail on the mainmast characterized the "old boats.” The last of these was launched in 1910. The "new boats” lacked topsails and generally had spoon-shaped bows. As internal combustion technology improved and regulations demanding oysters be dredged only under sail were relaxed, the sailing rigs were relegated first to auxiliary, then to backup, status and finally removed in the 1950s.

Commercial schooners largely disappeared from New Jersey by 1930. Four Delaware dredgeboats survive as passenger vessels and another forty work the fishery as motor vessels. The A.J. Meerwald, launched in 1928, has been restored by the Delaware Bay Schooner Project and sails as a floating classroom.

Schrabisch, Max (b. Mar. i, i869;d. Oct. 27, 1949). Archaeologist and writer. Max Schrabisch was born in Stettin (Pomern), Germany, to Julius Schrabisch and Emma Meinert Schra-bisch. He was educated in Berlin at the Royal Real Gymnasium, the Royal Conservatory of Music, and the University of Berlin. In i890, at the age of twenty-one, he immigrated to the United States and arrived in Hoboken. Between i902 and i906 he was a private secretary to Gen. Carl Schurz. Schrabisch taught music and authored numerous books, articles, and essays concerning political and social issues. From i920 through i924, he was a writer for the Paterson Morning Call.

It is not known what sparked his interest in archaeology, but between i900 and i940 he located and documented hundreds of prehistoric sites in northern New Jersey, southern New York, and northwestern Pennsylvania. By today’s standards, Schrabisch’s excavation techniques were primitive, but his Indian Site Survey volumes, published by the New Jersey Geological Survey, are still basic reference tools. Schrabisch was a member of the American Eugenics Society, American Anthropological Society, Passaic County Historical Society, American Ethnological Society, and the New York Academy of Sciences.

Max Schrabisch at Bear Rock near Boonton, 1914.

Schreyvogel, Charles (b. Jan. 4, 1861;d. Jan. 27, 1912). Painter, sculptor, and lithographer. Charles Schreyvogel was the second of three sons born to German immigrant shopkeepers, Paul and Teresa Erbe Schreyvogel, in New York City. During the artist’s childhood the family moved to Hoboken, where he lived and worked for most of his life. As a young man, Schreyvogel tried several professions, but by i880 settled on lithography and art teaching. In 1887, he traveled to Europe for three years and studied at the Munich Art Academy with Carl Marr and Frank Kirchbach. Ironically, Schreyvogel’s interest in depictions of the American frontier originated during his stay in Europe.

After returning to the United States, in 1893 he made the first of many extended trips West. During the 1890s, however, he sold very few Western paintings and relied upon portrait and miniature painting to support himself and his wife, Louise Walther. Success, when it came, arrived virtually overnight. Schreyvogel’s exhibition of My Bunkie (1899) at New York’s National Academy of Design in i\1900 generated national recognition. Despite criticism by America’s premier Western artist, Frederic Remington, Schreyvogel enjoyed consistent popularity during the early twentieth century. After Remington’s death in 1909, Schreyvogel became known as the greatest living painter of the American West, a reputation that was cut short by his early death in 1912.