Lower Alloways Creek. 45.7-square- mile township in Salem County. First owned by John Fenwick, most of the land in this township was purchased by settlers between 1676 and 1683. It was originally part of the Monmouth Precinct, so named by John Fenwick in honor of the duke of Monmouth; it was set off from that tract of land in 1760. The agricultural nature of the township gave rise to its early industries of a cannery and several mills. Half of its territory is salt marsh, which is home to muskrat, the main food served at an annual dinner held in the township. The settlements of Harmersville and Maskell’s Mill and the villages of Canton and Hancock’s Bridge are part of the township. Hancock’s Bridge, a small waterside village, is home to the William Hancock House, now operated as a museum by the state of New Jersey; it was the scene of a massacre during the Revolutionary War, when British and Loyalist troops surprised and killed sleeping militiamen. Although Lower Alloways Creek Township is still predominately rural, PSE&G’s nuclear power-generating station on Artificial Island in the township is Salem County’s largest employer. In 2000, the population of 1,851 was 96 percent white and the median household income was $55,078. For complete census figures, see chart, 133.

Lower Township. 27. 4-square-mile township in Cape May County. Lower Township is a collection of areas, each with its own name, but governed as one municipality. Whalers established the first permanent settlement of Europeans along Delaware Bay around 1640. They followed the whales here from Connecticut and Long Island and named their settlement New England Town. Later, the name Town Bank was given to the area, supposedly by William Penn, because of the high banks that overlooked the bay. When Cape May County was officially established in 1692, Town Bank was the first county seat. Lower Township was created by the state legislature in 1798. Cold Spring Presbyterian Church, a National Historic Landmark, was organized in 1714 and the oldest marked grave dates to 1742.

During World War II, Naval Air Station Wildwood was a training base for aircraft carrier dive bomber pilots. The huge wooden hangar is on the National Register of Historic Places and is being restored as a museum and memorial to the thirty-six men who died in training. The township is the embarkation point for the Cape May-Lewes Ferry, which provides car and passenger service across Delaware Bay.

The 2000 population of 22,945 was 96 percent white. The median family income was $38,977. For complete census figures, see chart, 133.

Loyalists. The strength and importance of Loyalism in New Jersey is surprising, given that there were no great conflicts or disputes in the colony during the turbulent decade before the American Revolution began in 1775. New Jerseyans of all political persuasions, including the able Loyalist royal governor, William Franklin, rejected parliamentary taxation and resented imperial interference in local affairs. Overall, the colony’s citizens were in agreement regarding the imperial crisis until resistance became rebellion and rebellion eventually led to the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

New Jersey’s Loyalists included royal officials, merchants, large landowners, Anglican clerics, Quakers, High Church Dutch (especially in Bergen County), yeoman farmers, skilled artisans, laborers, apprentices, shopkeepers, schoolteachers, and slaves. Clearly, they came from all socioeconomic groups and cut across ethnic, familial, gender, occupational, racial, religious, and sectional lines. The factors that led them to choose allegiance to the Crown over political separation were just as diverse. Some who committed themselves to the British side based their decision on a deeply held belief in the supremacy of Parliament and the Crown’s legitimate right to rule; they revered the structure of the British government and the principles on which it was based. The fear that revolution and republicanism would lead to anarchy was uppermost in the minds of these Loyalists. Some New Jerseyans chose Loyalism for economic motives, especially merchants who depended on trade with British manufacturers or held government contracts. Loyalist clergymen defended the established Anglican Church and its imperial role. Yet the decision to remain loyal did not always hinge on any overarching economic or ideological motives; local struggles, as well as personal animosities and experiences, also played a role. Many slaves escaped from their masters and joined the Loyalist ranks, believing that a British victory held the greatest hope for their permanent freedom. In Bergen County, the decision to remain loyal was influenced in large part by the religious factionalism among the members of the Dutch Reformed Church.

Although Loyalism in New Jersey drew upon a cross section of the population, a group of wealthy, well-respected men formed its core. The colony’s attorney general and speaker of the assembly, Cortlandt Skinner and his brother Stephen (the former East Jersey treasurer), were active Loyalists who held office under the royal governor. Other leading Loyalists were affiliated with the New Jersey Supreme Court: Chief Justice Frederick Smyth; Justice David Ogden; Isaac Ogden, a Newark lawyer and sergeant of the court; and John Antill, the court’s secretary. In addition, most members of the governor’s council joined the Loyalist ranks, including Daniel Coxe, Peter Kemble, John Lawrence, David Ogden, James Parker, Stephen Skinner, and Frederick Smyth, although Kemble and Parker can more accurately be described as neutralists. All of these men were political conservatives who believed the Patriot cause would undermine the rule of law and encourage disrespect for government. Finally, the core group of New Jersey Loyalists included the Anglican ministers Thomas Bradbury Chandler and Jonathan Odell, who promoted the established church and advocated a more active role for Anglicanism in the colonies.

During the Revolution, many of New Jersey’s Loyalists served the British in a military capacity by joining the British regulars and forming Loyalist regiments. The largest of the regiments, the New Jersey Volunteers, was organized and commanded by Cortlandt Skinner (who held the rank of brigadier general). These Loyalist units were involved in guerrilla warfare and made foraging raids into exposed areas of the New Jersey countryside, often from bases in British-occupied New York City and Staten Island. One of the most effective of these Loyalist units was the Black Brigade, led by a former slave from Monmouth County known as Colonel Tye (his given name was Titus). The Board of Associated Loyalists, headquartered in New York City, helped to coordinate the activities of the Loyalist regiments. Other, independent Loyalist bands roamed the countryside, marauding and plundering the farms and homes of known or suspected patriot sympathizers. Loyalist civilians also served the British forces as contraband smugglers, counterfeiters, guides, harbor pilots, ordnance suppliers, propagandists, saboteurs, and spies.

Those residents of New Jersey who chose to remain loyal to the Crown often faced legal reprisals from Patriot committees and the state government, including fines, imprisonment, disfranchisement, confiscation of property, and banishment. Loyalists also suffered physical abuse, tarring and feathering, the destruction of their homes and property, social ostracism, and even death. During the course of the war, and especially at its conclusion, several New Jersey Loyalists left the state and settled in Nova Scotia, Canada. Others departed for England. A few found new homes in other parts of the British Empire or in neighboring states. However, the large majority remained in New Jersey. Some eventually filed claims with the Loyalist Claims Commission, which was set up in 1783 by the British government to indemnify Loyalists with pensions for their service during the war and to compensate them for loss of property.

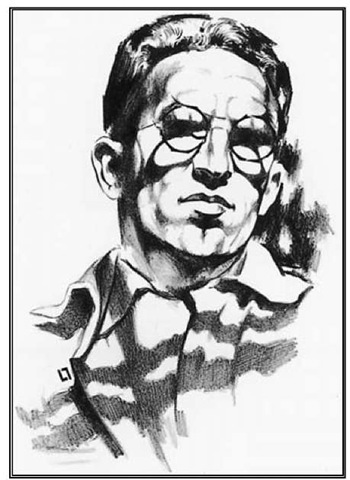

Lozowick, Louis (b. Jan. 1, 1892; d. Sept. 9, 1973). Graphic artist and author. Louis Lozowick was born in Ludvinovka, Ukraine. After attending the Kiev Art School for two years, young Louis came to the United States in 1906, joined his older brother, and attended Barringer High School in Newark. His fine arts education continued at the National Academy of Design and Ohio State University. Lozowick lived abroad between 1920 and 1924, where he was immersed in the international art world and influenced by the machine aesthetics of the time. He discovered lithography in 1923, one year before he returned to the United States to settle in New York City. He authored Modern Russian Art in 1925. As a member of the New Masses executive board, his articles and illustrations enhanced the radical journal. Considered a member of the Precisionists, Lozowick’s subject matter in the 1920s dealt almost exclusively with the strength and dynamism of machinery and the basic forms of urban buildings. During the Depression years he received a number of WPA commissions. Lozowick created imagery reflecting the extreme social conditions of the Depression and his leftist politics. In 1931 Lozowick married Adele Turner; after the birth of their son Lee in 1943, the family moved to South Orange where an active life included travel, teaching, writing, and exhibiting. Louis Lozowick died in South Orange.

Louis Lozowick, Self-Portrait, 1930. Lithograph, 15 13/16 x 11 in. (sheet).

Lucent Technologies. A manufacturer and developer of telecommunications-related systems, Lucent Technologies became an independent company in April 1996 with the breakup of AT&T. It was the largest IPO (initial public offering) in U.S. corporate history at that time.

Lucent’s origins can be traced back to two AT&T subsidiaries: the Western Electric Manufacturing Company and Bell Laboratories. Western Electric had been AT&T’s exclusive equipment maker since 1881. In 1984 Western Electric’s charter was assumed by AT&T Technologies. Bell Laboratories had been the corporation’s R&D (research and development) unit since 1925. The originator of such technology as the transistor, the laser, and electronic switching, Bell Laboratories has occupied a distinguished position in American science. When AT&T formed Lucent in 1995 from AT&T Technologies and Bell Laboratories, the firm’s focus was network equipment, switching devices, and business communications hardware.

After Lucent became independent, it spent $32 billion in stock and cash between 1997 and 2000 to acquire or merge with thirty telecommunications-related companies. In 2002, faced with vast contractions in the telecommunications industry and massive operating and restructuring losses, Lucent laid off thousands of employees and replaced its leadership. With its headquarters in Murray Hill, and operations in more than ninety countries, Lucent Technologies remains one of the top twenty-five employers in New Jersey with 16,700 employees in the state.

Lucioni, Luigi (b. Nov. 4, 1900; d. July 22, 1988). Painter and printmaker. Luigi Lucioni was born in Malnate, Varese, Italy. In 1911, young Luigi came to America along with his father Angelo, a coppersmith, and mother Maria Beati Lucioni. They settled in North Bergen. Lucioni studied art at Cooper Union and later at the National Academy of Design while supporting himself as a newspaper illustrator. Later in life he was a longtime resident of Union City. For their precise draftsmanship and an emphasis on capturing the truth of each object, his superlatively realistic still lifes and landscapes earned accolades from critics and collectors alike. In 1932, Lucioni became the first contemporary American artist to have an artwork, Pears with Pewter, purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Luigi Lucioni died in New York City.

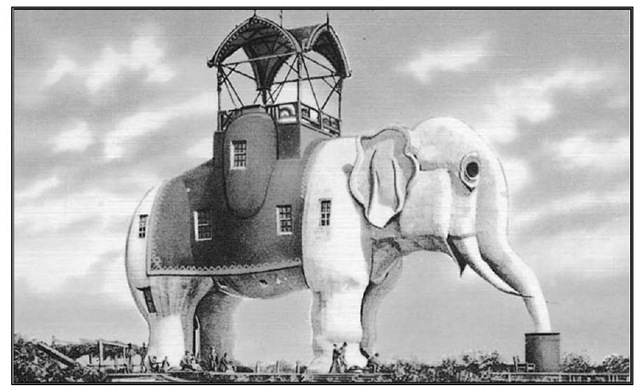

Lucy the Elephant. The nation’s only six-story elephant, Lucy was the brainchild of Philadelphian James Lafferty, Jr., who built the wooden elephant to help attract prospective homeowners to lots around what was then Egg Harbor Township (now Margate). Lucy was built in 1881 at a cost of $25,000; Lafferty took out a patent on his creation the following year. The application, in part, read: "My invention consists of a building in the form of an animal, the body of which is floored and divided into rooms. The legs contain the stairs that lead into the body.” Lucy’s legs and tusks are each twenty-two feet long. Her ears are seventeen feet long and weigh 2,000 pounds each. Her body is thirty-eight feet long and her head, sixteen feet high. Her total weight is ninety tons. An estimated million pieces of wood, plus 250 kegs of nails and four tons of bolts, were used in Lucy’s construction.

Lucy was one of three wooden elephants built by Lafferty. The Light of Asia, which stood near the beach in what is now Lower Township, was torn down in 1900. The Coney Island Elephant, on Surf Avenue, was built in 1884, and burned down in 1896. Lucy survived through the years, although she was buried knee-deep in the sand after a 1903 storm, and in 1904, while serving as a tavern, she caught fire after rowdy drinkers knocked over oil lanterns.

The Gertzen family, longtime owners of Lucy, donated the elephant to Margate in 1970. The Save Lucy Committee was formed; the elephant was moved two blocks south to its present location on July 20, 1970. The project director called it "the most unusual moving job” in the company’s history, likening it to "moving the Sphinx.” In 1971, Lucy the Elephant was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Ludlow, George C. (b. Apr. 6,1830; d. Dec. 18,1900). Lawyer and governor. A graduate of Rutgers College in 1850, George C. Ludlow practiced law and followed the example of his father and his grandfather by becoming active in Democratic politics. After serving in a number of local offices, he was elected to the state senate in 1876 and became its president in 1878. A split in the Democratic party at the convention of 1880 made him a compromise candidate for governor, and he was elected by 651 votes in the closest gubernatorial election in New Jersey history.

In his private law practice, Ludlow had been retained by the Pennsylvania Railroad; his opponent, Frederick A. Potts, was an influential stockholder in the Jersey Central Railroad. For most of the nineteenth century New Jersey was notorious for the influence railroad interests wielded in both the State House and the governor’s office, and many feared that Governor Ludlow would become a tool of the railroads. To the contrary, his administration was marked by persistent efforts to require railroads and other corporations to assume a fairer proportion of the state’s tax burden.

During the nineteenth century railroad corporations in New Jersey paid no local taxes. They held large and valuable tracts of land, and their exemption from taxation eroded municipal tax bases and increased the burden on local taxpayers. During the legislative session of 1882 an assemblyman complained that the railroads owned one-third of the property in Jersey City, valued at more than $19 million— all of which was exempt from local taxation. The fact that the value of the exempted properties in this city exceeded the total value of twelve of the twenty-one counties in the state increased the resentment of citizens toward the wealthy corporations, and made the issue of "equal taxation” more important to the electorate.

Lucy the Elephant, Margate.

In the legislative session of 1882 Ludlow was confronted with corporate power when a bill sponsored by the Central Railroad that would have allowed the corporation to increase its capital stock without consulting the stockholders reached his desk. Calling it illegal and immoral, Ludlow vetoed the bill, but was overridden by large majorities in the legislature. Ludlow also vetoed a bill that would have given the Pennsylvania Railroad exclusive control over valuable tracts in Jersey City that had been reclaimed from the river. Only a bribery scandal prevented the override of another veto as Ludlow denounced the bill as "an abuse of legislative power.”

For the remainder of his administration Ludlow courageously persisted in having the corporations in New Jersey pay their share of taxes, devoting the bulk of his 1883 and 1884 messages to the issue of railroad taxation. Continually confronted by Republican-controlled legislatures dominated by special interests, he was able to accomplish little except to raise the moral tone of state government, and to set the stage for a more equitable and effective tax system signed into law by his successors. He left the governorship consigned to political oblivion by powerful enemies. Quietly practicing law in New Brunswick in 1895, he was appointed to the New Jersey Supreme Court by a scandal-ridden Gov. George Werts. Ludlow died in 1900.

Lumberton. 12.87-square-mile township in Burlington County founded in i860. Most of the land area was originally part of Evesham Township, one of the county’s first townships. Other portions were taken from Medford, Eastampton, and Northampton (which later became Mount Holly). At first, Lumberton consisted of two villages, Lumberton and Hainesport, both situated along the south branch of the Rancocas Creek. Hainesport was broken off as a separate municipality in i924, following a dispute over school capacity.

Lumberton’s dominant geographic features were farmland and the Rancocas Creek, and it was once a busy stopping point for side-wheeler steamboats carrying produce from central Burlington County to markets in Philadelphia and points south. One side-wheeler, the Barclay, was built along the creek in Lumberton. The town’s historic central village and agrarian surroundings remained largely unchanged until the i950s, when the Hollybrook residential development was first erected, in large part as off-base housing for personnel from Fort Dix and McGuire Air Force Base. Lumberton’s major growth spurt began in the i980s, when it became one of the county’s fastest-growing towns. Major developments are located north and northwest of the village, while the Route 38 strip has evolved into a commercial and industrial corridor. Efforts have continued to preserve some remaining farmland along the Medford and Southampton border. The 2000 population of 10,461 was 78 percent white and 14 percent black. The 2000 median household income was $60,57i. For complete census figures, see chart, i33.

Lutheran Church. Though Lutherans have never been numerically dominant in New Jersey (in seventh place among New Jersey Christian denominations in i936 and in fourth place in 1990), they have been a part of New Jersey religious life since the European colonization of the territory in the seventeenth century. As an organized religious community, North American Lutheranism was born in New Jersey. Prior to the arrival of Hein-rich Melchior Muhlenberg and other clergy of the Halle Mission, the story of Lutherans in New Jersey was written in three chapters: established Lutheranism in New Sweden, clandestine Lutheranism in New Netherland, and the refugee Lutheranism of the German Palatines. The royal Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden founded the first Lutheran church organization in North America, establishing a military chaplaincy at Fort Christina (now Wilmington, Delaware) beginning in 1640, and later a colonial consistory to care for a network of village churches and fortress chapels as well as mission outposts among the Lenape. What is believed to have been the first Lutheran eucharistic liturgy in North America was celebrated by the Church of Sweden chaplain to Fort Elfsborg (present-day Elsinboro Township, Salem County) in 1643. Even after the transfer of the Swedish colonies to Dutch rule and the abridgement of the Swedish colonial consistory, many Swedish Lutheran clergy remained, caring for their congregations and training candidates for ordination. In 1702, one such spiritual descendant of the Lutheran Church in New Sweden, Lars Tol-stadius, founded the congregation of Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church in Swedesboro, the oldest New Jersey Lutheran congregation in continuous existence.

Frontispiece from the parish register of the Saint James "Straw Church” congregation, Phillipsburg, c. 1769.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Lutherans of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, now independent of Spanish rule and Roman Catholic domination after an eighty-year war, had become an unwelcome minority among the Calvinist majority of their compatriots. Their style of worship was too high-liturgical for Dutch Reformed taste, and their loyalty to the Spanish monarch (simply because the Spanish Crown was the established secular authority in the Netherlands prior to independence) had not been forgotten. Gov. Peter Stuyvesant complained bitterly to the directors of the Dutch East India Company about these undesirables being dumped on his doorstep but was told to leave them alone as long as they were law-abiding and brought profit to Dutch East India stockholders. Stuyvesant interpreted the directive literally and applied it grudgingly to the Lutherans, forbidding them (together with other religious minorities such as Jews and Roman Catholics) to form legal corporations for religious purposes or to appoint their own clergy in the settlements of New Amsterdam (Manhattan Island) and Bergen (Hudson and Bergen counties, New Jersey), which were directly under his control. A number of Lutheran pastors from Holland and Germany did manage to infiltrate New Netherland, as it happened, and to establish Dutch- and Low German-language congregations, which would survive the transition from Dutch to British rule.

Refugees from religious persecution and war began arriving in the new British mid-Atlantic colonies from New Jersey to Maryland in the last two decades of the seventeenth century, opening a floodgate of German immigration to that region that would not subside until well after the American Revolution. These Palatine Lutherans brought with them their own refugee clergy (such as Justus Falckner, who died in 1723) and adopted Dutch Reformed church polity (and the Dutch language, where this was insisted on by the elders of the older Dutch Lutheran congregations) in order to resolve conflicts that arose between clergy and congregations. Accordingly, a Dutch-style classis was organized in New Jersey among Lutheran clergy along the Raritan by Johann Christoph Berkenmeyer (1686-1751). The Raritan classis met in a synod under Berkenmeyer as superintendent in 1735 to settle a conflict between Johann August Wolf and his congregation at Smith-field (present-day Oldwick). It would take another decade, and a very different type of Lutheran leader and church order, to reconcile Pastor Wolf and the people of Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church.

It would fall to Heinrich Melchior Muhlenberg (1711-1787), son of Einbeck in Lower Saxony, educated at the University of Halle, to finally resolve the Wolf matter and to set North American Lutheranism on a clearly organized course for the first time since the days of New Sweden. A pastor of the royal Evangelical Lutheran Church of Hanover, over whose consistory presided the monarch of both Hanover and Great Britain, Muhlenberg was to be among the first of many pastors of the Halle Mission who were officially commissioned by the Church of Hanover and sanctioned by the Church of England for service in the American colonies. He was blessed with passion and patience and with physical stamina equal to the task of tending a pastoral charge that extended from the Hackensack to the Susquehanna.

Muhlenberg introduced an English-language liturgy for American Lutherans based on that of the Savoy Chapel in London, though many continued to worship and receive religious instruction in German or Dutch. From his organizing and unifying ministry two great synodical associations were born, the Ministerium of Pennsylvania, the primary focus of Muhlenberg’s efforts and established during his lifetime (1748), and the New York Ministerium, established in 1792, parent synod of the present Lutheran Synods of Upstate New York, Metropolitan New York, New England, and New Jersey.

In the nineteenth century, others carried on the work of unifying and organizing the Lutherans of North America, and of providing for the education of an indigenous clergy. Until Samuel Simon Schmucker (1799-1873) founded the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg in 1826, Lutheran clergy in America either received their theological education in Europe or they attended the Presbyterian Princeton Theological Seminary. While Schmucker, himself a Princeton graduate, was grateful for the Presbyterian connection and the opportunity it afforded for Lutherans to participate in the mainstream of American Protestantism, he was convinced that a distinctive Lutheran theological identity had to be nurtured through Lutheran theological education at Lutheran institutions and through a national Lutheran synod. Gettysburg Seminary was Schmucker’s response to the former concern and the General Synod was his strategy for the latter. The New York Ministerium, and with it most of the Lutheran congregations of New Jersey, would maintain this bond for a century and a half.

The United Lutheran Church in America (ULCA) organized a separate New Jersey Synod at Trenton in 1950. The New Jersey Synod has remained intact with territory coextensive with that of the state through two subsequent national Lutheran denominational mergers: the formation of the Lutheran Church in America (LCA) in 1962 and the formation of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) in 1988. Most New Jersey Lutherans have, as a consequence, known a continuous association as a synod for half a century. The ELCA New Jersey Synod comprises 195 congregations today. The New Jersey Synod’s more conservative Lutheran counterpart, the New Jersey District of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod (LC-MS), includes 59 congregations.

Of necessity and under the influence of the nineteenth-century German Lutheran "Inner Mission” movement of social ministry, New Jersey Lutherans have responded to social injustice and need with dedication. An example is the founding of the Kinderfreund (Children’s Friend) home for orphans, women, and the elderly in Jersey City (later reconfigured as the Lutheran Home nursing home and since 1994 operated as a multipurpose pastoral care and social service community center by the Episcopal Diocese of Newark). The New Jersey Synod and the Episcopal Dioceses of Newark and New Jersey cooperate in other shared service in the areas of youth and family camping ministry, as well as chaplaincy to seafarers in the ports of New York and New Jersey.