Freneau, Philip (b. Jan. 2, 1752; d. Dec. 19, 1832). Poet, editor, and mariner. Philip Freneau was the son of Pierre Fresneau (the s was later dropped) and Agnes Watson, daughter of an old New Jersey family. When Freneau was a boy, the family moved from New York to Mount Pleasant (Matawan). Educated privately and at a grammar school in Manala-pan, he entered the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) at the age of sixteen. There he met James Madison and Hugh Henry Brackenridge, who were highly influential. It was at Princeton that Freneau’s gifts as a writer began to emerge. A poem he cowrote with Brackenridge, "The Rising Glory of America,” was read at their commencement in 1771.

Required to help support the family after his father’s death, Freneau tried teaching for several years after graduation, with little satisfaction. In 1772 he published a collection of poems, The American Village. By 1775 he had made his way to New York City, amid growing tensions between England and the colonies. His poems about the crisis, both satirical ("General Gage’s Soliloquy”) and patriotic ("American Liberty”), as well as his political essays, won him the nickname "Poet of the Revolution.”

In early 1776 Freneau headed for the West Indies after a bitter exchange with critics, taking a position with a prominent planter in Santa Cruz. The island’s exotic scenery led him to produce some of his best poems, including "The Beauties of Santa Cruz.”

Freneau was captured by the British en route back to America in 1778. Released shortly afterward, he joined the New Jersey militia and served on blockade runners, but was captured again in 1780. The harsh conditions aboard the prison ship Scorpion, where he was held for six weeks, left Freneau a virtual skeleton and led him to write "The British Prison-Ship.”

For the rest of his life Freneau alternated between periods as an editor with a variety of newspapers, and as a mariner. After a period of recuperation from his imprisonment, in 1781 he joined the staff of the Freeman’s Journal, a Philadelphia paper in which many of his poems and essays appeared. However, the financial problems that would plague him throughout his adult life led to Fre-neau’s decision to return to the sea in 1784. It was during this period that he produced some of his most highly regarded poems, including "The Hurricane,” which is notable for its use of symbolism and philosophical ambiguity.

Freneau returned to New Jersey to marry Eleanor Forman of Freehold in 1790, and to become editor of the New York Daily Advertiser. At the request of Thomas Jefferson, Freneau moved to Philadelphia in 1791 to oversee publication of the politically influential National Gazette, leaving his family at Mount Pleasant. When the paper failed in 1793, he returned to New Jersey to start the Jersey Chronicle, which failed in 1796. He spent 1797-1798 as editor of the Timepiece and Literary Companion. Financial difficulties, as well as marital discord, forced his return to the merchant marine between 1803 and 1807. During these years he continued to write poetry and revise earlier pieces, publishing such collections as The Miscellaneous Workks of Mr. Philip Freneau (1788), Poems Written and Published During the Revolutionary War (1809), and A Collection of Poems, on American Affairs (1815). The final years of his life were spent with his family on the farm in Monmouth, always on the verge of poverty. Freneau was eighty years old when he died in a blizzard in 1832.

Frerichs, William C. A. (b. Mar. 2,1829; d. Mar. 5, 1905). Painter. Born in Ghent, Belgium, William Frerichs came to New York City in 1850 after a varied career in Europe. He specialized in portraits and pristine landscapes. Little is known of his earliest years in the United States. At some point before the Civil War he married Clara Butler and taught at Greensboro College in North Carolina. In 1880 he moved to Newark and after the death of his first wife married E. Walen. In Newark he began a successful art school, and his landscapes often graced the front windows of shops on Broad Street. He was popular with the Newark press and was usually referred to as "the Professor.” He died at the home of his son in

Tottenville, New York. Many of his paintings are held by the Newark Museum.

Fuld, Caroline Bamberger Frank (b. Mar. 16, 1864; d. July 18,1944). Philanthropist and businesswoman. Caroline Bamberger and her brother, Louis, who worked together in the dry goods business, moved from Baltimore to Philadelphia in 1883. In 1892, her brother, her first husband, Louis Meyer Frank, and Felix Fuld became business partners, and bought out the bankrupt firm of Hill and Craig in Newark. After selling the stock, they organized the firm of L. Bamberger and Company, and opened a department store at the corner of Market and Halsey streets in Newark on February 1, 1893. Caroline Frank and the three men worked together in the store to make it prosper, developing new advertising methods.

Frank was widowed in 1910; three years later she married her brother’s other business partner, Felix Fuld. By that time, the firm was in a new building and employed 2,500 people. The business soon became one of the largest mercantile companies in the United States, with annual sales of $35 million by 1928. After the death of her second husband in 1929, Fuld lived with her brother. She and Louis sold L. Bamberger and Company to R. H. Macy in June 1929, several months before the stock market crash.

In 1930, Caroline Fuld and Louis Bamberger endowed the Institute for Advanced Study, to be located in Princeton, on the condition that Dr. Abraham Flexner undertake its organization. They contributed approximately $18 million for the Institute’s development. Bamberger became president and Fuld vice president until the Institute was formally established in 1933, when they became life trustees.

The Institute for Advanced Study, the first of its kind in the United States, was dedicated to "the pursuit of advanced learning and exploration in fields of pure science and high scholarship to the utmost degree that the facilities of the institution and the ability of the faculty and students will permit.” It attracted scholars from all over the world. From its earliest years, the Institute was internationally recognized as one of the world’s leading centers for research, and the presence of Albert Einstein and Oswald Veblen was a factor that attracted others.

Caroline Fuld maintained her commitment to service. In 1931 she was elected director of the National Council of Jewish Women, where her special interests were vocational guidance and employment programs. She was also active on the Child Welfare Committee of America. Fuld gave generously of her fortune throughout her life, but in keeping with full-service gas stations. In 1949, a gas station in Hackensack lured customers away from rival stations when it offered gasoline at a discount to motorists who pumped the gas themselves. Lobbying by the New Jersey Gasoline Retailers Association led to the passage of a law that year banning self-service at gas stations in New Jersey. That ban has remained in force ever since, making New Jersey one of only two states in the nation (Oregon is the other) to prohibit self-service. Repeated attempts since 1949 to repeal the ban have failed. Opponents of self-service argue that, if it were introduced to New Jersey, it would severely inconvenience senior citizens and the disabled, create a safety hazard, cause gasoline prices to rise, result in layoffs, and jeopardize the survival of independently owned service stations. These opponents of self-service point to the fact that gasoline prices in New Jersey are below the national average. Those who want to eliminate the ban argue that New Jersey’s low gas prices are due to low gas taxes, and that even if self-service were introduced, full-service pumps would remain an option for those who preferred them. A poll of motorists in 2000 found public support for the ban, and the legislature continues to back it. There seems to be little chance that self-serve gas pumps will appear in New Jersey any time soon.

Fulper Pottery Company. The Flem-ington and Trenton potteries survived for many years by changing their product line from utilitarian stoneware to art pottery to tableware. In 1858, Abram Fulper bought Samuel Hill’s Flemington pottery, where Fulper had been making stoneware and red-ware for Hill. Hill’s pottery had been operating since about 1810, and in later years the Fulper family often used this as the starting date of their pottery as well. Following Abram’s death in 1881, his sons Charles, William, George, and Edward took over management of the operation; however, the Fulper Pottery Company was not officially incorporated until 1899. J. Martin Stangl, a German glaze chemist, began working for the pottery in 1911. In 1928, the Fulper Pottery opened a second factory in Trenton in the old Anchor Pottery, principally for the manufacture of tableware. Stangl bought the company in 1930 and closed the original factory in Flemington in 1935, officially changing the company name to Stangl Pottery at that time.

The pottery’s earliest wares were stoneware crocks and jugs having a salt glaze on the outside and dark-brown slip coating on the inside. Cobalt blue decoration was sometimes added to the surface and wares were marked with the company name and the size in gallons. By 1900, the use of heavy stoneware vessels was passing from favor. Lighter materials, such as glass, were helping homemakers perform many of the same household tasks as stoneware had. The company decided to change its product focus, and in 1909 introduced the VaseKraft (also Vase-Kraft) line of art pottery. For this line, a series of art glazes was applied over the traditional stoneware body. This body was fashioned into a variety of ornamental shapes, including vases, lamp bases, jardinieres, bowls, bookends, tobacco jars, candleholders, and the like. Many of the shapes were based on classical Asian and European forms that the Fulpers had seen in art museums in New York and Philadelphia, but had simplified to accommodate the thick glazes and heavy clay bodies. The glazes were given evocative names for marketing purposes, such as "Elephant’s Breath,” a luminous black, or "Alice Blue,” from the popular song about Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter. Stangl developed significant glazes for this art line after he joined the company, including a wide range of crystalline, matte, and flambe glazes. The company’s display won an award at the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco.

Jewish tradition, sought to make her donations anonymously. When she died, Fuld left a large portion of her fortune to the Institute for Advanced Study and to public health, welfare, and cultural institutions in Newark.

Fulper Pottery Company trade catalog.

Stangl managed the operation with increasing autonomy in the 1920s and began development of a tableware line made in red earthenware and decorated with brightly colored glazes. The Trenton factory was opened in 1928 in order to accommodate production of this new line, while the art pottery with stoneware body continued to be made in Flemington, so that the radically different bodies and glazes would not contaminate each other in the same factory.

In 1984, the daughters of William Fulper III revived the company’s many signature glazes into a line of art tiles, called Fulper Glazes, which the original firm did not make in quantity.

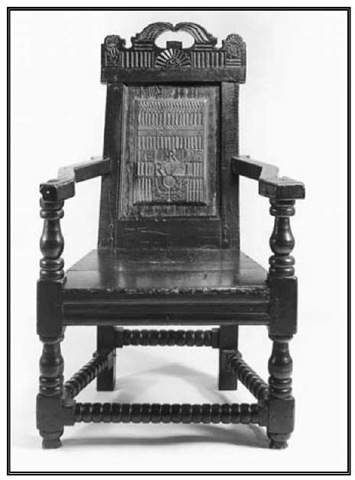

Furniture making. Religious discrimination against his Quaker beliefs banished Robert Rhea from his native Scotland in the early 1680s, and he came to America and settled near Freehold in Monmouth County. He farmed his several-hundred-acre tract of land, and with carpenter-joiner skills learned in Scotland, he also made furniture. A wainscot armchair inscribed in its carved back panel with the initials of Robert Rhea and Janet Hampton Rhea (his wife) and dated 1695 bears testimony to his ability.

While Rhea’s chair may be the earliest documented piece of New Jersey furniture, there were other craftsmen working in the province by the time he arrived. In the rural environment of the colonial period, in order to produce enough income to support their families, craftsmen generally alternated their trades with other income-producing activities, fitting them into the seasonal rhythms of farming or fishing, or combining them with occupations such as shopkeeper, surveyor, undertaker, or justice of the peace.

New Jersey remained largely rural throughout the eighteenth century, supplying food and raw materials, including quantities of wood, to the nearby urban centers, Philadelphia and New York. Only a few towns in the province grew to a size that could support more than one furniture maker: New Brunswick, Elizabeth, and Newark in East Jersey, and Mount Holly, Burlington, and Salem in West Jersey; and by the end of the century Trenton, as the seat of government, attracted many craftsmen to its environs.

Rural craftsmen worked in much the same way urban craftsmen did, usually in smaller shops, employing fewer hands and managing with fewer tools, but using the same basic knowledge. A furniture maker had to know the techniques of joining, turning, carving, and finishing, or he had to hire a person trained in the skills he lacked. Training was acquired through an apprenticeship system, traditionally a seven-year period spent in the shop of a master craftsman, perhaps working alongside a journeyman who had completed his apprenticeship but had not attained enough wealth to establish his own shop. In more rural areas an apprenticeship might be as short as three or four years. Often family members were the only help in smaller shops; larger shops might employ several journeymen and apprentices.

Wainscot armchair made by Robert Rhea, Freehold, 1695.

The tools in a furniture maker’s shop would vary, depending on his ability as a craftsman, the demands of his market, and his wealth. He would need implements for splitting, sawing, planing, turning, joining, and carving wood. Tools were a costly investment, so they would be well cared for and commonly were handed down from one generation to the next.

The forests of New Jersey provided plenty of raw material for making furniture. Oak, cedar, pine, and walnut in early furniture, and by the mid-eighteenth century, maple, cherry, and sweet gum were used as primary woods, the visible structural wood with finished surfaces; with pine, ash, cedar, and poplar used as secondary woods for drawer interiors, shelving, backing, and bracing. Although mahogany became available early in the eighteenth century through the West Indies trade, a preference for native walnut persisted in Quaker-dominated southwest New Jersey late into the century.

Among the wide range of furniture forms the colonial craftsman was capable of producing, evidence provided by extant examples as well as inventories indicates that dressing tables, chests, high chests, chest-on-chests, linen presses, tea tables, card tables, dining tables, sideboards, candle stands, tall-clock cases, desks, armchairs, side chairs, stools, and settees were made and used in New Jersey.

Different techniques used in the construction of two chest-on-chests, one by Richardson Gray, working in Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth), 1795 to 1803, the other by Mahlon Thomas in Mount Holly, also at the turn of the century, are of interest. Gray used cherry wood for his chest; Thomas used walnut. Both pieces have ten drawers, three small over seven wide, and ogee bracket feet. Thomas embellished his with fluted quarter columns; Gray did not, reflecting the different tastes (or pocket-books) of their customers. The waist molding is attached to the top section of the Mount Holly chest, which fits together by sliding the top across two horizontal tracks from the front. In more traditional fashion, the waist molding on the Elizabethtown chest is part of the bottom section and the top fits down inside it, making this chest slightly more awkward to assemble. Imprinted paper labels in two drawers identify Gray’s work. Thomas’s handwritten inscription is more informative: "Bottom/Made 29th Nov 1799” and, on the top, "Made by Mahlon Thomas in Mount Holly Jany 7th i8oo”—confirming that furniture styles continued in popularity long after the traditionally quoted end dates when they would have been surpassed by newer fashions in more cosmopolitan centers.

Matthew Egerton is one of the most recognized names in the history of New Jersey furniture makers. Three generations of the family worked in New Brunswick over a period of nearly a century, but Matthew Jr., the middle generation, active from the 1780s to the 1830s, is the best known. His work was considered so important in the early years of the twentieth century (much of it believed then to be by Matthew Sr.) that nefarious antiques dealers are known to have applied faked, newly printed Egerton labels to furniture by unknown makers and to have transferred original labels from lesser pieces to finer ones. The Egertons made inlaid furniture in the fashion of the federal period, but Matthew Egerton, Jr., was catering to vernacular tastes introduced by seventeenth-century Dutch settlers in the Hudson Valley when he made a kast in the i790s. Another furniture form unique to the Bergen County area is the Hackensack cupboard, with glazed doors above, paneled doors below, and diagonal reeding applied liberally to the surface. Chip-carved spoonracks and rush-seat, turned chairs with solid vase-shaped splats, saddle-shaped crestrails, and vase-turned legs ending in pad feet also are typical of the Hudson Valley area.

Most remarkable for the longevity of their business and the quantity of work they produced and inspired is the Ware family of South Jersey. Four generations spanning three centuries, the 1780s to 1940s, made rush-bottom, slat-back, turned chairs. Characteristic of early Ware chairs are accentuated bulbous turnings on the front stretcher, ball front feet, and pointed ball finials on the stiles supporting the graduated (often five) arched slats.

A simpler form of rush-seat, three-slat, turned chair was made in central New Jersey in the nineteenth century. These low-back chairs have stiles, flattened on the front with a drawknife, ending about two inches above the top slat, rounded leg tops, simple stretchers, and stenciled or free-hand decoration, usually flowers or fruits, applied to the slats, stiles, and legs, and seats often painted yellow.

Changes in social structure and business practices that began in the early years of the new republic continued at an accelerated pace in the nineteenth century as new transportation systems and new technology moved the nation toward full-blown industrialization. Partnerships were formed to meet the demands of expanding markets, and to stay competitive in a growing industry, production methods shifted toward specialization. The range of skills of a master craftsman were no longer in demand, resulting in the decline of his social status. Jobbers supplied parts, such as seats, arms, or legs for chairs, which semiskilled, low-wage workers assembled and finished at the factory. Local retail business shrank as wholesale orders for more distant markets increased, requiring construction of big warehouses that changed the landscape forever.

Cabinetmaker John Jelliff worked in Newark, with various partners and numerous employees, from 1836 to 1890. Jelliff and Company produced furniture of the highest quality in all the Victorian revival styles for every room in the house, from entrance hall to bedchamber, and for church, bank, lodge, and office, all by hand. All their work was done under one roof, moving the business toward modern industrial practices. Jelliff, however, was one of the last manufacturers to offer a complete line of furniture in New Jersey. This was because shops with man-powered machinery still outnumbered steam-powered factories in New Jersey into the 1870s, while midwestern furniture manufacturers moved toward fully mechanized operations much earlier.

Fancy chair factories such as David Alling’s in Newark, T. R. Cooper’s in Schraalenburgh, Collignon Brothers in River Vale, and Gardner Brothers in Glen Gardner were prolific in the nineteenth century. From warehouses in New Jersey, New York, and Philadelphia, they shipped portable seating furniture throughout the United States and to South America and the West Indies. Advertisements boasted of patents such as those issued to the Col-lignons for their folding chairs, popular on steamships, and to the Gardners for perforated plywood, practical for railroad waiting rooms. Few of these businesses survived to the end of the century in New Jersey; they either closed or moved away.

The eclectic excesses of the Victorian period and the dehumanization of factory workers in the late nineteenth century led to a desire for reform. Ideals that John Ruskin and William Morris had advanced in England as part of the Arts and Crafts movement found a receptive audience in this country. Gustav Stickley, a leader of the movement in

America, promoted the ideals of simplicity, individuality, and dignity of labor. He began as a chairmaker in rural Pennsylvania and ultimately designed not only complete household furnishings but the houses themselves, at middle-class prices, without abandoning his goal of financial success. In 1910 he built Craftsman Farms at Morris Plains. It never materialized as the utopian community he envisioned, but for five years Stickley made his home at the log house which today is a National Historic Landmark.

Colonial Revival, a component of the Arts and Crafts movement and related to a national historical consciousness inspired by the nation’s 1876 centennial celebration, reached its zenith in the 1920s under the leadership of New England entrepreneur Wallace Nutting, a former minister, who made honest reproductions of colonial furniture (not fakes with built-in stress marks). Responding to market demands created by this revival, Samuel Brown and Harry Phares developed a successful business reproducing Queen Anne and Chippendale furniture, which they operated from 1923 to 1929 at Mount Holly.

Today craftspersons working at Peters Valley and elsewhere in the state continue to uphold the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement using traditional woodworking techniques to create their own masterpieces.

Although he was not the first to conduct polls, Gallup’s originality and strength were in his ability to formulate appropriate questions. Because of his background in journalism, he was a very effective spokesperson for his profession.

Gage, Margaret Kemble (b. 1734; d.Feb. 9, 1824). Wife of a British general. Margaret Kemble was born in Piscataway, daughter of wealthy merchant Peter Kemble and Gertruyd (Bayard) Kemble. Her grandmother came from an aristocratic Greek family, the Mavrocordatos. Margaret, a woman of intelligence, charm, and beauty, was well known among the socially elite. She married British general Thomas Gage in Morris-town on December 8,1758. Gage, Gen. George Washington’s chief nemesis, became the most important British general in America during the Revolution. Many believed that Margaret spied for the Americans during the battle of Lexington and Concord, providing them with military secrets to help protect them from British attack, though this has never been verified. However, Margaret departed for England in August of 1775 at the request of the British government. Her image is preserved in a famous portrait by John Singleton Copley, who considered it his best portrait of a woman.