Dayton, William Lewis (b. Feb. 17, 1807; d. Dec. 1, 1864). Lawyer, politician, and diplomat. William Lewis Dayton was born in Basking Ridge. After graduating from Princeton in 1825, he taught school and studied law in Somerville until admitted to the New Jersey Bar in 1830. He married Margaret Elemendorf Van Der Veer in 1833, and they had seven children. Dayton began his political career in the New Jersey legislature in 1837 where he served before accepting an appointment to the New Jersey Supreme Court. In 1841 he resigned to practice law in Trenton. William Pennington, the governor of New Jersey, appointed him to complete the unexpired term of Samuel Lewis Southard in the U.S. Senate, where he served until March 1851.

In 1856, Dayton was nominated to run for vice president on the Republican ticket. Although defeated, Dayton became a prominent national political figure and supported Abraham Lincoln in both the nominating convention and presidential campaign of i860. Because of his loyalty, Lincoln appointed Dayton U.S. minister to France. Despite Napoleon III’s outspoken sympathy for the Confederacy, Dayton implemented successful diplomatic strategies that prevented French recognition of the Confederate States of America. By the time of his death in i864 from an apparent stroke, Dayton could see the impending collapse of the Confederacy.

Deal. 1.8-square-mile borough lying along the Atlantic Ocean in Monmouth County. The Hogswamp Creek branch of Deal Lake borders the borough to the west. The area was settled as far back as i670 by Thomas Potter from Deale, England, and was designated on early maps as Deal Beach, encompassing land south of Lake Deal. Other landowners of the tract prior to 1700 include Whyte (White), Jeffries, Drummond, and Tucker. In early 1700 the Long Branch/Deal Turnpike cut through the tract and later became Norwood Avenue. In 1849, U.S. Lifesaving Station No. 6 was established on property donated by Abner Allen. Major residential development of the tract began in i894 when Theodore S. Darling purchased a boardinghouse along with another large portion of land south of it. The Darlington Train Station was built in 1894. In i896, Darling sold his property to the Atlantic Coast Realty Company. Many of America’s wealthiest and most prominent entrepreneurs built mansions along the ocean.

In 1898, Deal seceded from Ocean Township to form a separate borough. The borough is predominantly made up of large, single-family homes with a small business district. In 2000, the population of i,070 was 94 percent white. The median household income was $58,472.

Deborah Heart and Lung Center. The Deborah Heart and Lung Center, a i6i-bed hospital, is located in Browns Mills, Burlington County. Philanthropist Dora Moness Shapiro established Deborah Hospital in i922 as a tuberculosis sanatorium that would treat all patients, regardless of their ability to pay. After antibiotics controlled tuberculosis, Deborah changed its focus to include cardiovascular disease, and Charles Bailey, M.D., one of the pioneers of open-heart surgery in the 1950s.

Deborah. Today the only hospital in New Jersey devoted exclusively to the cardiac and pulmonary specialties, Deborah offers a range of surgical and nonsurgical options, as well as a full-service ambulatory care center. The Deborah Hospital Foundation, a network of 68,000 volunteers, raises funds to support research and treatment.

Decorative arts. "Decorative arts,” shrouded in the mystery of museum jargon, are nothing more than household objects, made by human hand and used in the furnishing of dwellings. These household items can be very plain or very fancy, depending on their purpose, and the geographic situation, aesthetic inclination, and financial condition of the householder.

The difficult part in understanding New Jersey’s decorative arts has been documenting objects that were made here versus those that were imported from elsewhere. In colonial times, pinioned between two major economic and cultural centers, New Jersey seems not to have produced a distinctive regional aesthetic. German, English, and Dutch influences seeped through different parts of the state, depending on the region and the period. The styles favored in Dutch-dominated upstate New York and the Delaware Valley region north of Philadelphia both strongly influenced the home furnishings of preindustrial New Jerseyans. New Jersey was not isolated enough to produce quirky vernaculars like those of Hadley, Connecticut, or Pennsylvania’s Mahantongo Valley. Indeed, New Jersey was so much in the middle of what was going on in New York and Philadelphia, in addition to being a major trade route between the two cities, that it is probable that everything made in New Jersey showed some degree of influence from one or the other—or both.

Still, New Jersey has always been a place where decorative arts were made. As early as the 1690s there was an active delftware manufactory in Burlington, managed in absentia by Dr. Daniel Coxe of London. Perhaps the most important pottery in seventeenth-century America, the Coxe pottery apparently produced both white and blue-and-white tin-glazed earthenware. Unfortunately, none of this work survives today.

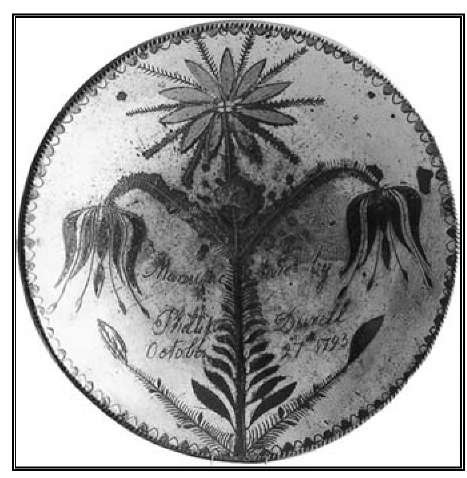

Although there was extensive production of utilitarian redware and stoneware in eighteenth-century New Jersey, few documented examples are known. A single splendid sgrafitto plate, dated 1793, demonstrates the work of Phillip Durell, a redware potter in Elizabeth. More is known about James Morgan, owner of the earliest New Jersey stoneware pottery, which operated in Cheese-quake (South Amboy), beginning in about 1775. On the other hand, very few surviving artifacts can be proven to be from the Morgan pottery.

Phillip Durell, pie plate, 1793. Pottery with slip and sgraffito decoration, d. 13 3/4 in.

Glassmaking in New Jersey was influenced both by English and German entrepreneurs, as well as by Philadelphia’s proximity to the southern flatlands of the state. Owing to its huge stands of wood and plentiful sand—two essentials in glassmaking—by the early eighteenth century South Jersey was a center of American glass production.

Producers of luxury goods such as stylish furniture and silver wares found themselves in a double bind in colonial and federal New Jersey. The most affluent families typically looked to New York in the northern part of the state, and to Philadelphia in the south, for their finest household goods. Hence, documented cabinetmakers and silversmiths from before 1800 are scarce. Abraham Dubois was a silversmith born in 1738 in Salem County. His career is archetypal, in that he probably trained in Philadelphia, and worked in New Jersey until 1777. At this point he completed the migration, finishing out his career as a silversmith in New York. One of the few families who seemed to stay put was the Lupp family of New Brunswick. Peter Lupp and his son Henry, as well as other relatives, William and Lawrence Lupp, were all silversmiths in New Brunswick in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Likewise, furniture making in preindus-trial New Jersey was made more difficult by the closeness of two of colonial America’s most important style centers. New Jersey furniture makers are difficult to identify, but documented examples provide clues to the many furniture makers who thrived here. Probably the earliest chairmaker in New Jersey history was Lawrence Pierson, from New Haven, who was among the first settlers of Newark in 1666. He made the so-called Yale President’s Chair, which was brought to Newark in 1666 and subsequently returned to New Haven. However, Pierson stayed behind, and he must have produced furniture for the Newark colony during the last quarter of the seventeenth century. Not a single piece is known today. Similarly, a single chair, made by Robert Rhea of Freehold in 1695, survives as the earliest known New Jersey chair. Rhea must have made other examples, but they are either lost, unknown, or misattributed.

Oddly enough, the richest body of documented New Jersey furniture is tall-case clocks. A surprising number of clockmakers left behind pieces that have survived to the present, but this is probably attributable to their habit of signing the clock faces. The case-makers remain as elusive as ever, with some exceptions. Linked to the clockmakers are the Matthew Egertons, Jr. and Sr., who produced some of the finest clock cases and federal-style furniture known from New Jersey in their New Brunswick shop between the 1760s and the 1800s.

Vernacular chairs, such as Windsors, were known to have been made at local shops in the eighteenth century in New Jersey. The best-known producer of distinctive ladder-back chairs was Maskell Ware (b. 1766) of Road-stown. Likewise, the many Dutch-descended chairmakers in Bergen County in northern New Jersey are known only through a fairly small number of simple pieces that bear the initial stamps of their makers.

The industrial revolution did a great deal to enhance New Jersey’s position as a producer of household goods. However, the first quarter of the nineteenth century followed the pattern established in the eighteenth century. Some goods were produced for local customers, while others, mostly at the high end, were brought in from New York and Philadelphia. This would remain essentially true until railroads and other improvements in transportation made the exportation of New Jersey-made goods profitable.

As the industrial revolution transformed American manufacturing, four distinct New Jersey regions rose up as giants in decorative arts production. Southern New Jersey, centered around Vineland and Millville, became a major center for industrially produced glass, while Trenton became the "Staffordshire of the New World” with its vast output of pottery and porcelain. Northern New Jersey, centered in and around Newark, became the leading center for work in silver and gold, while Paterson and Union City became the major producers of domestic textiles, especially silk and machine embroideries.

The first attempt to introduce stylish tablewares on the English model was by David Henderson (d. 1845), an entrepreneur who established the D. and J. Henderson Pottery in Jersey City in 1829. The Amboys continued to be a pottery center throughout the nineteenth century. Like Jersey City, the various, often short-lived potteries produced molded yellow stonewares and English-style brown-glazed or Rockingham wares.

Porcelain was only briefly attempted in New Jersey before the 1850s. The Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company was the earliest producer of porcelain in New Jersey, operating only between 1825 and 1828. A single small bowl survives to document this little-known firm’s output. It was in Trenton in the early 1850s that potters like William Young and William Bloor began the first successful experiments in porcelain production that would establish Trenton as the ceramics center of the eastern states.

New Jersey’s glass industry continued to develop in the southern region. The Bridgeton Glass Works, a bottle-making factory established in 1836, was celebrated for its historical flasks, and both continued and confirmed a pattern of commercial-use glass that would dominate the nineteenth century. The one notable exception was the Jersey Glass Company, a Jersey City glass firm established by brothers Phineas and George Dummer, which produced both cut and pressed glass from 1824 to 1862. The Jersey City site was clearly chosen because of its proximity to New York, just across the Hudson River. Ironically, while the firm was a success for a long time, very few of its wares have been documented.

New Jersey’s textile history is equally rich and complex. The Rutgers Factory, an early Paterson textile mill, was operated by Col. Henry Rutgers in the 1820s and employed one hundred workers. The Eagle Print Works, a textile printing firm, was established in Belleville by 1830. More typically, small-scale textile producers ruled localized markets in the first half of the century. The celebrated New Jersey coverlet weavers, using imported jacquard technology, produced their deep blue and white or red and white coverlets all over New Jersey from the 1820s to the 1840s.

There were many mostly anonymous cabinetmakers in New Jersey’s major towns and young cities, whose work today is unknown but for the occasional labeled example. Lemuel and Daniel Crane of Newark hold a special place in New Jersey furniture history, because of their 1829 apprenticing of a young Connecticut boy by the name of John Jelliff. Jel-liff and Company would go on to become New Jersey’s largest furniture maker, operating in Newark from 1835 until 1890. Other firms known to have produced significant amounts of furniture, such as Newark’s Douglas and Company and Kirk and Jacobus, are all but unknown save for documentary evidence.

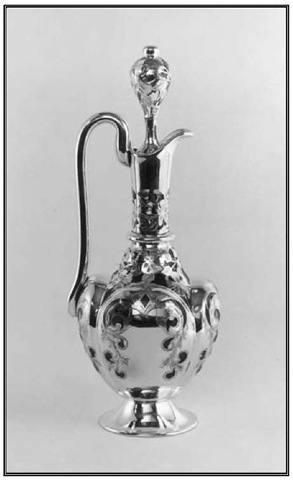

The furniture industry in New Jersey began to wane as industrialization and transportation made the American market bigger and more interconnected. On the other hand, the ceramics and textile industries began to grow because of this interstate development, as did the precious metal industry. Electroplating silver was an early industry in Newark, and in fact the related technique of silver deposit on glass and ceramics was perfected by the Alvin Manufacturing Company of Newark and Irvington in 1886. Newark’s most famous plating operation was established in the 1870s by Thomas Shaw, who had worked at Elkington and Company in Birmingham, England. Shaw’s factory was built to produce plated wares exclusively for Tiffany and Company.

Alvin Manufacturing Company, Irvington, Moorish-style wine ewer, c. 1886-1894. Glass with silver overlay, h. 13 7/8 in.

By the end of the nineteenth century Newark would become one of the major sterling silver production centers, including the enormous Tiffany and Company works in the Forest Hill neighborhood. At the same time that Newark’s silver industry was burgeoning, its production of gold jewelry was also on the rise. Tracing its roots to a six-man shop on Broad Street, opened in 1801 by Epa-phras Hinsdale, the firm of Taylor and Baldwin is considered to be the first of Newark’s major industrial producers of gold jewelry. Profiting from an influx of skilled German jewelry workers in the 1840s, scores of Newark goldsmiths would dominate the American jewelry marketplace by the end of the century. English names such as Aaron Carter and Enos Richardson were joined, starting in the 1860s, by German jewelry makers such as Ferdinand G. Herpers and George Krementz, who would become legends in America’s jewelry industry.

Although the first experiments in porcelain making predate the Civil War, it was not until the late 1870s that New Jersey ceramic tablewares seriously entered the competitive arena with English and French products. An Irishman, William Bromley, Sr., worked at Ott and Brewer in Trenton with Walter Scott Lenox. When Lenox branched out on his own in 1889 with the Ceramic Art Company, he began a tradition of fine china production in New Jersey that survives to this day.

Through the first quarter of the twentieth century, New Jersey remained a national powerhouse of decorative arts production.

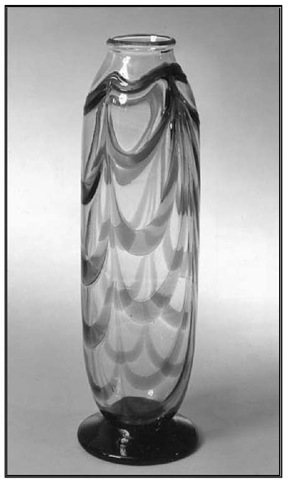

South Jersey’s glassworks, Newark’s gold and silver factories, and Paterson’s silk and textile mills were all going strong. The Arts and Crafts movement, flourishing in America in the decades before World War I, produced its own New Jersey progeny, in small-scale operations such as the Clifton Art Pottery in Newark and the celebrated Fulper Pottery Company in Flemington. In Vineland, Victor Durand established an art-glasshouse in the 1920s that rivaled his contemporary Louis C. Tiffany’s Queens’ glasshouse.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, the production of household furnishings in New Jersey is a shadow of what it once was. In this way New Jersey’s history parallels the nation at large. There are more New Jerseyans than ever before, and they are still buying decorative arts to fill their homes. But, more often than not, what they buy comes from somewhere else.

WPA Glass Works, vase with amethyst looping, c. 1940-1942. Blown, colorless and amethyst glass, h. 16 in.

Decoys. The coastal waters and rivers of New Jersey are the resting area for a variety of migratory ducks that feed on the grasses and wild rice native to the state. Hunters use hand-carved wooden decoys (artificial birds) to attract and hold the attention of resting ducks and to entice game within shooting range. Duck hunting in New Jersey peaked in the nineteenth century when the demand for game food was high; this period is referred to as the golden age of decoys. The Federal Migratory Bird Act of 1913 ended unrestricted commercial bird hunting, allowing duck hunting only as a sport. The new regulation indirectly lowered the demand for decoys throughout New Jersey; yet they are still used by hunters and valued by collectors.

The decoy, also called a stool, is made of two pieces—the head and the body. The body, typically of white cedar, is made of halves, using either a gouge or an adz to hollow the wood. The carved head, made from pine or cedar, is attached with a dowel, nail, or screw. In the case of a broken head, a different carver often constructs a replacement. The bottoms of decoys are frequently branded with the owner’s name, to ensure return.

Decoys are designed to mimic the species of ducks present within the region and to perform best under local water conditions. In New Jersey, the two distinct classifications of duck decoys are Delaware River and Barnegat Bay decoys.

Decoys of the Delaware River have rounded bottoms and a linear shape for increased visibility on the rough river water. These decoys have a full extended breast and carefully detailed feather painting and carving. John English (1852-1915), of Florence, New Jersey, is the most renowned decoy carver on the upper part of the Delaware River. His decoys were carved with raised wings and incised details. On the Lower Delaware River, John Blair (1842-1928) of Philadelphia was carving sleeker stools with detailed feather painting. Through the work of these men, the upper river became known for feather carving, and the lower river for feather painting. Neither of these men was from a carving tradition, but their work is highly valued and collected. Through collectors, the decoy has surpassed its utilitarian function and is valued for its composition and stylistic appeal.

The black duck, the mallard, and the pintail are commonly represented as Delaware River decoys. The decoys of this region tended to remain in excellent condition since they were used on fresh water. Used on the Delaware ducker, a two-man hunting skiff, the decoys were released in groups of thirty to forty-five stools. The hunters could then row upriver and wait for ducks to arrive, at which time they would scull quietly toward the resting birds.

By the 1940s and 1950s, the dredging of the Delaware River had deepened and straightened the river, causing the water to flow faster. A flat-bottomed decoy began to be used on the Delaware to accommodate this fast water. The effect of dredging, shoreline development, pollution, and the 1913 Migratory Bird Act has been the steady decline of duck hunting on the Delaware River.

Most decoys used for coastal hunting throughout the state are similar to the decoys being carved around Barnegat Bay. The marked differences between the Barnegat Bay decoy and the Delaware River decoy are its flat bottom and simplistic details. Sometimes called "dugouts,” these decoys tended to be small in size and extremely lightweight. Some of the bay decoy heads are tucked to the side of the body. Durable white cedar construction kept the decoys in shape for years of hunting use. Henry Van Nuckson Shourds (1861-1920), of Tuckerton, is highly praised for the quality and quantity of decoys he carved in his lifetime. Over a forty-year period, he is said to have carved an average of 2,000 decoys a year.

Two types of ballast are used to weight the Barnegat Bay decoy body. Carvers from the Tuckerton area poured molten lead into a rectangular carving within the base of the stool—this maintained a clean line on the exterior of the body—while carvers from the head of the bay nailed a rectangular lead pad into the bottom of the stool. With five ounces of lead ballast, the decoy could flip itself upright in the water. A leather anchor cord was fastened to the bottom of the stool, and the flock of decoys could be anchored in the bay. Hunters normally used a skiff called the Barnegat Bay sneakbox to conceal themselves close by their floating decoys to await their targets.

With the decline of waterfowl hunting in New Jersey, more decoys are found on collectors’ shelves than in the water. During the 1920s, private collections of decoys began to form. Now valued as folk art, the work of the nineteenth-century New Jersey carvers is displayed in museums across the state. Many contemporary carvers no longer create decoys for utilitarian purposes, but instead for artistic competitions and decorative display.

White-tailed doe in snowy Jockey Hollow National Park, Mendham.

Deep Cut Park. Located on fifty-two acres in Middletown Township, Deep Cut Park is named for a narrow gorge carved by a stream. Originally consisting of one hundred acres, this property has had several owners, including organized crime boss Vito Genovese. Beginning in 1935, Genovese constructed stonewalls, formal gardens, ornamental pools, and a working model of Mount Vesuvius. Subsequent owners added exotic trees, greenhouses filled with succulents and orchids, and more extensive gardens. In 1977 the owner, Marjorie Sperry Wihtol, willed half her property to the Park System, which then purchased additional acreage. The park was opened to the public in 1978. Deep Cut Park also includes a rose garden, honored as one of the twenty-five official All-American Rose Selection Trial gardens, and has one of the largest horticultural libraries on the East Coast.