Colonial wars. While under English rule, the colony of New Jersey faced little danger of foreign or Indian attack. On its frontiers were the colonies of New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. In view of the strong Quaker influence in government, it is not surprising that New Jersey was inclined to provide at best only minimal support to the government in times of war.

The few subtribes of the Delaware Indians in New Jersey, such as the Hackensacks, Minisinks, and Raritans, caused almost no trouble, although in the mid-i75os there was a flare-up along the Delaware River in northwestern New Jersey. The Treaty of Easton in 1758 brought lasting peace. The Indians of New Jersey sold their land claims in exchange for a reservation established for them at Brotherton in Burlington County. By 1776, Native Americans in New Jersey had almost totally vanished.

Although avoiding wars on its own soil, New Jersey gradually increased its contributions to intercolonial war efforts. During King William’s War (1689-1697), however, the colony offered no aid to New York and the New England colonies in their projected Canadian offensives. During Queen Anne’s War (17021713), with a single governor overseeing New Jersey and New York, the colony was expected to aid in prosecuting the war on the New York frontier and in Canada. In i7o6 New Jersey provided about five hundred troops, who were mustered in New York City but not used. New Jersey volunteers joined a force collected near Albany under the command of Col. Francis Nicholson in 1710 and 1711, but failure of British assistance along the Saint Lawrence River resulted in cancellation of the Canadian invasions.

With time, Great Britain’s rivalry with France and Spain for the North American empire intensified as ever-enlarging spheres of interest overlapped. New Jersey traders and land seekers joined colonists from New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia in the westward advance.

Gov. Lewis Morris prevailed upon the General Assembly in 1740 to vote for raising volunteers for an American force to join a British expedition against the Spaniards in the West Indies and Caribbean. New Jersey contributed three companies of one hundred men each, under the commands of James Hooper, George Thomas, and Robert Farmar. Rampant disease and the disastrous assault on Cartagena on the Colombia coast in March i74i forfeited many lives. Of the 3,700 Americans in the British expedition, only i0 percent returned home. Neither New Jersey nor other northern colonies gave any further assistance in the so-called War of Jenkin’s Ear (1739-1744).

During the last two wars of the colonial period, New Jersey made a more determined commitment. The royal governors had instructions for their colonies to share in the burden of supplying men and provisions. In King George’s War (1744-1748) the legislature, although dominated by pacifist Quakers, appropriated £2,000 toward financing the New England force that assisted in the capture of Louisbourg, on Cape Breton Island, on June 27, 1745. For a planned attack on French-held Crown Point on Lake Champlain in i746, New Jersey raised five companies of one hundred men each. The Jersey Blues (as the volunteer militiamen were now called), commanded by Col. Peter Schuyler, arrived at Albany in September to link up with Gen. William Shirley’s army. Delays in pay, bad food, and defective weapons contributed to a heavy desertion rate and also a mutiny in May i747. Expected assistance from the Iroquois was mostly not forthcoming. The expedition was canceled, and the New Jersey troops returned home. Another New Jersey regiment was being raised at the time the war ended in 1748.

The colony rarely participated in intercolonial war and Indian conferences. New Jersey failed to send commissioners to the Albany Congress in i754, and the legislature rejected the Albany Plan of Union because it would "affect our Constitution in its very vitals.” From 1755 to 1757 the colony maintained blockhouses in Sussex County to ward off threatened Indian attacks.

During the French and Indian War, the defeat of Gen. Edward Braddock, commanding regulars and Virginia, North Carolina, and Maryland militia in western Pennsylvania on July 9, i755, prompted the New Jersey legislature to vote funds (although less than requested by Gov. Jonathan Belcher) to raise troops for military campaigns against the French. New Jersey, however, was the only colony that failed to fill its assigned quota of troops, providing only half of the one thousand men requested. The reasons given were economic hard times and the contributions from other colonies, which were deemed sufficient for victory.

New Jersey troops joined the force led by William Johnson directed against Crown Point. Col. Peter Schuyler commanded the Blues, half of whom were stationed at Oswego and half at Schenectady. A French army under the Marquis de Montcalm captured Oswego on August i4, i756, and Schuyler and the New Jerseyans became prisoners of war.

The New Jersey regiment was revived in i757, when the colony voted to raise 500 troops, one-half of the quota assigned by the British commander-in-chief in America, Lord Loudoun. By early summer 1757, the new levies from New Jersey, commanded by Col. John Parker, had taken post at Fort William Henry on the lower end of Lake George. Parker, with 350 men from his regiment and a few New York soldiers, set off in twenty-two whaleboats to scout along the lakeshore, hoping to apprehend some detached French soldiers or their Indian allies. Parker’s flotilla was ambushed by 600 Indians in canoes at Sabbath Day Point; 100 of Parker’s men were killed and i50 made prisoners. Those who made it back to Fort William Henry fared no better. The fort, under siege, surrendered on August 9, 1757. Some of the captured New Jerseyans were among those slaughtered by Indians as the captives were marched toward Fort Edward. The surrendered New Jerseyans were allowed to go free on parole for eighteen months, after which time they could fight again.

Most of the i,000-man quota for 1758 was raised. The troops, commanded by Col. John Johnston, joined Gen. James Abercromby’s army at the site of the former Fort William Henry, which had been demolished. On July 5, Abercromby’s army, in twelve hundred boats, moved twenty-five miles up Lake George, debarking on a narrow peninsula connecting Lakes George and Champlain, a few miles from Fort Ticonderoga. Successive assaults on Fort Ticonderoga met with withering fire and ended in disaster. The British army withdrew. The New Jersey troops, kept as a rear guard and involved only in the final assault, suffered few casualties.

In the fall of i758 the New Jersey General Assembly reestablished the regiment at full strength, and also provided funds to build barracks in five towns for fifteen hundred soldiers (only the Old Barracks in Trenton survives today). The Jersey Blues, now commanded by Col. Peter Schuyler, who had been released as a prisoner of war, again did duty in the Lake Champlain area. Enlistments of troops were voted for i759 through i762, although quotas were only partially filled. Some New Jersey troops accompanied Gen. Jeffrey Amherst’s army in i760 in the taking of Montreal.

During the French and Indian War the New Jersey legislature refused to levy any new taxes. Although Parliament reimbursed the colonies for one-third of their war expenses, New Jersey issued £347,000 in unsecured paper money during the war. At war’s end, New Jersey had the largest indebtedness of any of the colonies.

Colt, Peter (b. Mar. 28,1744; d. Mar. 17,1824). Businessman. Peter Colt was born in Connecticut, served as a deputy commissary general during the Revolution, and later as Connecticut’s state treasurer. In i793, he was hired by the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (SUM) as superintendent of the factory at the pay of $2,500 a year. Colt was not trained as an engineer, but he was practical and efficient. He scaled down Pierre L’Enfant’s ambitious plans for a massive aqueduct, which did not take into consideration the limited finances and scarcity of skilled labor at the time. Colt dammed a ravine to create a reservoir that fed a single raceway for the mills. To begin production before the water mills were ready in 1794, Colt set up a small, ox-powered mill that spun cotton. Economic troubles ended Colt’s term in 1796, when the society temporarily ceased operations. He worked for the Western Land Lock Navigation Company in New York, but returned to New Jersey in 1811, where he remained until his death. His sons, Roswell Colt (1779-1856) and John Colt (1786-1883), were instrumental in reviving the SUM in the nineteenth century. John Colt’s Paterson cotton mill made cotton duck used for the sails of the famed racing yacht America.

Colt Paterson number 3 belt model .31 caliber revolver in case.

Colt, Samuel (b. July 19, 1814; d. Jan. 10, 1862). Inventor and manufacturer. Samuel Colt was born in Hartford, Connecticut, the son of Christopher and Sarah Caldwell Colt. Even at a very young age, he was brilliantly inventive at tinkering with guns and machinery. Colt went to sea at sixteen, and while sailing to Calcutta came up with an idea for a practical revolving pistol. The revolver concept itself was not new, but Colt was the first to make it work by incorporating a pawl-and-ratchet gear similar to that used to keep a ship’s capstan from sliding backward. This securely held the cylinder in place and minimized the misfires and accidents that plagued earlier repeating firearms. To raise money for prototype guns and patent fees, Colt went on a lecture tour to demonstrate the effects of laughing gas to amused audiences.

By 1836, Colt had raised enough money for U.S., British, and French patents, and to set up a gun factory. The new firm, called the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company, was located in the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures industrial site along the Passaic River at Paterson. Colt demolished an old factory and replaced it with a new four-story gun mill dominated by a large central tower. A fence with pickets in the shape of guns surrounded the property. While in operation, the factory made handguns as well as rifles, carbines, and even revolving shotguns. All of these weapons used percussion caps and black powder cartridges; suitable metallic cartridges were years in the future. The most common guns were five-shot pistols. Many of these early Paterson Colt pistols are distinguished by a concealed trigger that appears when the gun is cocked, and by their lack of trigger guards. The guns were popular with individual buyers, but the large military contracts needed for profitable large-scale production were slow in coming. U.S. Army administrators and ordnance officers resisted the new technology; indeed, for years they resisted switching from outmoded flintlocks to percussion-cap weapons. The lack of large government contracts and the lingering effects of the Panic of 1837 bankrupted Colt’s Paterson operation, and it closed in 1842 after manufacturing only a few thousand weapons.

Although the Paterson factory closed, the weapons manufactured there eventually made Samuel Colt’s fortune. His revolvers began to catch on in the West, especially after the armed forces of the Republic of Texas bought some of the Paterson revolvers. Demand increased with glowing tales of the revolver’s efficiency during the Mexican War. By this time, Colt had opened a new plant in Hartford, Connecticut. He asked many of his former workers from New Jersey to move to the new factory. When Colt died in 1862, his gun was already a legend.

Colt’s Paterson factory was converted into a textile mill. Subsequent owners altered the complex over the years. The remaining Colt buildings were vacant after 1983 and were almost destroyed by a series of arson fires; restoration efforts are planned. Surviving Paterson Colt revolvers are desirable collectors’ items.

Colts Neck. 31.44-square-mile township in Monmouth County. Incorporated as Atlantic Township in 1847, it was renamed Colts Neck in 1962. There are references to Colts Neck as early as 1675. The derivation of the name is not positively known: it may have been because its location between Yellow Brook and Mine Brook forms a neck of land similar to that of a colt’s.

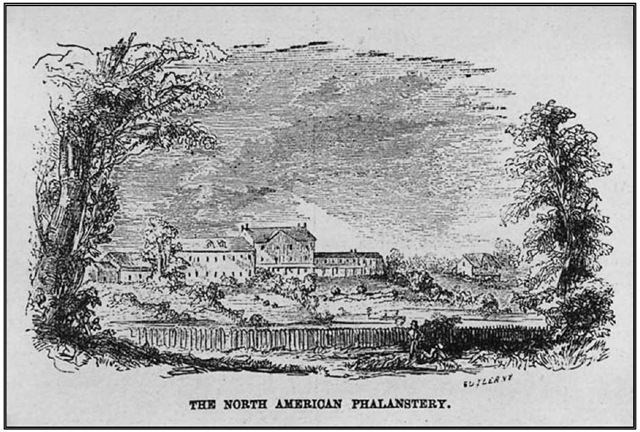

Early settlers were from England and Scotland. One of its most memorable residents was Capt. Joshua Huddy of the New Jersey militia who was executed by Loyalists toward the end of the Revolutionary War. At that time, Colts Neck was mostly rural, with mills and horse farms the economic mainstays. Laird and Company operated a distillery until 1850. From 1843 to 1854, the North American Phalanx, a cooperative community, prospered here. In the early 1900s, water, telephone, and electricity services were established and a town hall was erected in 1909. Residential development started in the 1960s and escalated through the 1980s. Today, Colts Neck is largely a residential area.

The 2000 population of 12,331 was 86 percent white and 8 percent black. The median household income was $109,190. For complete census figures, see chart, 130.

Combs, Moses Newell (b. Jan. 3,1754; d. Apr. 12, 1834). Manufacturer. Although his standing in Newark economic history is outmatched by others, most notably the inventor Seth Boyden, Combs deserves notice as the first entrepreneur to sell his own leather product—shoes—beyond his city’s borders. In so doing he became the leading Newark industrialist of his time.

Combs is believed to have been born in Newark in 1754, possibly 1753. As a young man he answered the call to arms on behalf of American independence in 1776 and served in the Continental Army for a year, followed by another year or so as an artillery sergeant with the New Jersey militia. In 1779 he married Mary Haynes, then in her late teens, and they had thirteen children. He has been depicted as a "little black-eyed man” of determined character.

Around 1780 he began tanning, using animal hides and tree bark to fashion leather articles. It was a Newark specialty dating almost as far back as the city’s settlement in 1666. In those early colonial days, journeymen tanners periodically went from house to house to transform hide into shoes. Newark’s earliest known practitioner, in the seventeenth century, was Samuel Whitehead, originally of Elizabeth. Tanners congregated at a watering place on or near Market Street in central Newark, and Combs was undoubtedly among them. By the early years of the nineteenth century, about a third of Newark’s labor force worked at shoemaking and other leather industries. As the tanning business became firmly established, Combs focused his attention on shoe manufacturing, and he was the first to deal with customers beyond the local area, especially in the South. One particular order for two hundred pairs of shoes placed by a client from Savannah, Georgia, in 1790 is regarded as a breakthrough for both Combs and Newark. As the historian John T. Cunningham observed, "He made Newark aware that money could be made by serving distant regions.” A visiting French aristocrat in the early 1800s estimated Combs’s workforce to be between three hundred and four hundred.

Circa 1840 drawing of the North American Phalanx, a commune located in Colts Neck during the mid-nineteenth century.

Combs was an ordained preacher and temperance advocate whose inclination for separatism caused him to distance himself from the mainline Presbyterian congregation and for a time operate his own house of worship. He found himself at odds with a church discipline he regarded as "arbitrary and tyrannous,” in the words of a biographer, who said this same impulse caused Combs to set free a black man he owned. (The emancipated slave, Harry Lawrence, was hanged in 1803 for poisoning his wife.) Aside from his business success, Combs is most noted for establishing a night school for his employees in 1794— the first of its kind in America. Apprentices learned reading, writing, and other basic skills free of charge in a two-story building Combs erected on Market Street near Plane Street, where he also held worship services. Combs operated the school until 1818, two years after his wife died. He was a cofounder and director of the Newark Fire Insurance Company and treasurer of the Springfield-Newark Turnpike Company. He moved to Randolph in Morris County, applied for a Revolutionary War pension in 1832, and died two years later.

Commerce and Industry Association of New Jersey. A free enterprise advocacy organization established in 1927, the Commerce and Industry Association of New Jersey (CIANJ) is made up of 850 companies, representing all areas of business and industry, for the purpose of promoting a favorable economic environment in New Jersey. The association’s board of directors includes members from businesses in northern New Jersey. CIANJ’s advocacy efforts include business-government networking sessions as well as legislative updates; educational programs, including roundtables for environmental and employment issues, breakfasts, and training programs; Commerce, a magazine launched in 1965, with a current readership of ten thousand; social opportunities and affinity-program discounts for members; leadership awards; a business and industrial directory of nearly nine thousand firms; and the Private Enterprise Political Action Committee (PENPAC). CIANJ also sponsors the Foundation for Free Enterprise, an outreach program launched in 1975 that provides numerous educational offerings at Ramapo College, such as the Learn about Business intensive seminar and the Free Market Study Conference for school students; a debate series for high school students; and a distinguished lecture series for college students. The foundation also offers an Understanding American Business seminar for teachers at New Jersey City University and a Making New Jersey Competitive seminar for public officials.

Commerce Bank. Founded in 1973 by Vernon W. Hill II, Commerce Bank and its parent holding company, Commerce Bancorp, have grown quickly. With an aggressive expansion plan, Commerce has become the largest independent bank holding company in New Jersey in assets and deposits. Headquartered in Cherry Hill, Commerce’s retail strategy includes offering extended hours and opening offices seven days a week. Choosing to expand through the establishment of branches rather than through the acquisition of other banks, Commerce had 114 branches in New Jersey and 46 offices in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New York in 2001.

Commercial Township. 32.5-square-mile township in southern Cumberland County. Once a major oystering center, Commercial was formed from Downe Township in 1874. Villages within the township include Bivalve, Laurel Lake, Port Norris, and Maurice town. The area’s prosperity has long been tied to the water. Once, millions of oysters were harvested annually in Delaware Bay.

When a rail line to Bivalve expanded the market for the Maurice River Cove oyster, Port Norris, the business center of the trade, became known as the oyster capital of the world. In 1922 shucking and packing sheds were erected near the docks of Bivalve and Shellpile so that oysters could be shipped off the shell more cheaply.

Maurice town, once the home of sea captains, is today an engaging town of antique shops and lovely old homes. Laurel Lake, which began as a summer resort in the late 1920s, now accounts for about half the township’s population.

As a result of a parasite that caused the death of almost the entire Delaware Bay oyster population in 1957 and the 1990s outbreak of a new oyster disease, the local economy now includes crabbing, fishing, and heritage tourism. The Delaware Bay Museum and the A. J. Meerwald, a 1928 Delaware Bay oyster schooner listed on the National Register of Historic Places, teach the traditions of the oystering and shipbuilding industries at Bivalve.

The 2000 population of 5,259 was 83 percent white and 13 percent black. The median household income in 2000 was $34,960. For complete census figures, see chart, 131.