Barkan, Alexander E. (b. Aug. 8,1909;d. Oct. 18,1990). Labor leader and political organizer. Alexander Barkan was born in Bayonne to Jacob and Rachel Barkan. A University of Chicago graduate, Barkan began his career in the labor movement as an organizer for the Congress of Industrial Organizations’ (CIO) Textile Workers Organizing Committee (TWOC) and its successor, the Textile Workers’ Union (TWU). Barkan married fellow TWU organizer Helen Stickno in 1942, with whom he raised two children. After World War II military service he returned to serve as political action director for the TWU from 1948 to 1955.

With the merger of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the CIO in 1955, Barkan joined the national AFL-CIO’s Committee on Political Education (COPE), and rose to its directorship in 1963. COPE directs labor’s electioneering efforts, and under Barkan’s leadership COPE played a major role in delivering a record victory to Lyndon Johnson and the Democratic party in 1964.

Later years presented greater difficulties as divisions within the AFL-CIO, declining union membership, and the efforts of rival political action organizations challenged labor’s influence on the Democratic party. Barkan, American labor’s political voice for a generation, retired as COPE director in 1981.

Barnegat. 34.9-square-mile township in Ocean County. The Dutch referred to the area as Barendegat, meaning "an inlet with breakers”; they established the first European settlement in 1664. Barnegat Village thrived on the basis of its proximity to Barnegat Bay and rich natural resources, including bog iron, fish and shellfish, and lumber. When Union Township was formed from parts of Dover and Stafford townships in old Monmouth County in 1846, Barnegat was one of the two principal villages in the new township. The village continued to grow as a port community and resort destination throughout the nineteenth century. Major industries included maritime commerce, shipbuilding, and glassmaking. Parts of Union Township were annexed to form Lacey Township in 1871, and Ocean Township was formed from parts of northeastern Union Township in 1876. Union Township’s piece of Long Beach Island also broke away, part becoming Harvey Cedars in 1894 and the rest Long Beach Township in 1899.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, railroads and other factors reduced Barnegat Village’s importance as a port, and its attraction to tourists waned. The village returned to its earlier economic roots. Today, many residents continue to look to fishing and marine trades for their livelihoods. In 1976 rapidly growing Union Township became Barnegat Township.

In 2000 the population of 15,270 was 95 percent white. The median household income in 2000 was $48,572. For complete census figures, see chart, 129.

Barnegat Bay. The largest body of water wholly within the limits of the state of New Jersey, Barnegat Bay runs from Point Pleasant southward along the entire inner side of the Squan Peninsula and halfway down Long Beach Island to the Bay Bridge between Manahawkin and Ship Bottom, where it meets the tidal currents of Little Egg Harbor. It is twenty-seven miles long, and from one to four miles wide. The bay is fed by the Metede-conk River, Kettle Creek, Cedar Creek, Oyster Creek, Forked River, Toms River, and Gunning River. In earlier years when its only connection to the ocean was at Barnegat Inlet, its upper end was very nearly fresh water. In 1926, however, the newly completed two-mile Point Pleasant Canal joined the bay with the Manasquan River estuary, and its currents and salinity have greatly increased since then. Barnegat Bay is a part of the Intracoastal Waterway, and is one of the most popular areas in the state for recreational boating, fishing, and crabbing. There are several sizable wildlife sanctuaries on Barnegat Bay, but much of the former open marshland along both sides is now extensively developed, with vacation and year-round homes on artificial lagoons.

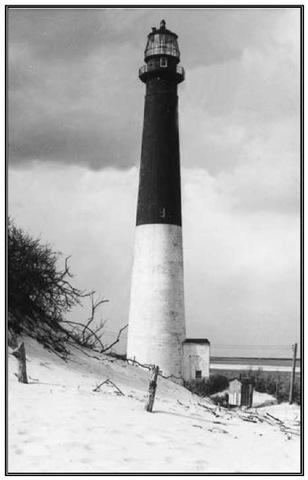

Barnegat Light. 0.72-square-mile borough on Barnegat Inlet at the north end of Long Beach Island in Ocean County. The name Barnegat is derived from an English cartographer’s misspelling of the Dutch Barendegat, "inlet with breakers,” given to the dangerous inlet by its discoverers in 1614. The shoals at the inlet’s entrance were so dangerous to shipping in foul weather that a lighthouse was built there in 1837. It was replaced in 1869 by the present 165-foot tower, which has not been lit since the 1920s but remains in a state park as the island’s most enduring symbol. In 1882 a vacation community called Barnegat City was established at the base of the lighthouse with two large hotels and a score of fine cottages, many of which survive in the town’s historic district. Around 1910 many Norwegian and Swedish immigrants began to settle in the area, and they soon built up a thriving fishing industry. Barnegat City was so often confused with the village of Barnegat on the mainland that its citizens voted in 1946 to change its name to Barnegat Light.

The 2000 population of 764 was 98 percent white. The median household income was $52,361.

Barnegat Lighthouse. Barnegat Lighthouse is located on the northern tip of Long Beach Island in the town of Barnegat Light. Construction of the present lighthouse began in 1857; it was completed in 1858. Equipped with a first-order flashing Fresnel lens, it flashed once every ten seconds at each point of the compass. The lens was removed in 1927 when the Barnegat Lightship took up station off Barnegat Inlet. The lens was returned to the town of Barnegat Light and is on exhibit in the Barnegat Light Historical Museum. The lighthouse is owned by the state of New Jersey and is now part of Barnegat Lighthouse State Park.

Barnegat Lighthouse, built c. 1858.

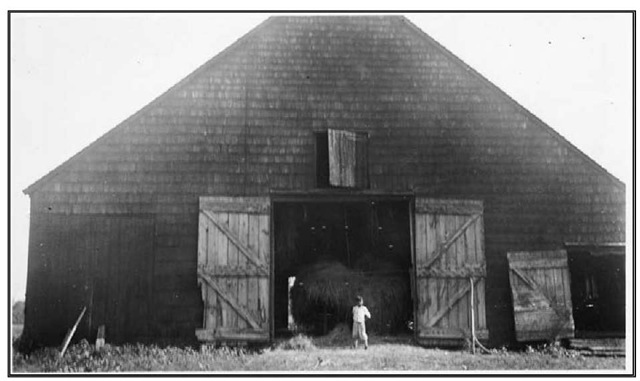

Barns. Described as more important in "situation, size, convenience, and good finishing” to a farmer than "his dwelling,” barns were vitally important to New Jersey settlers from the time the Dutch first began arriving in the area. In the agricultural period that followed there were three eras with much overlap, during which time barn types changed. The first was an early economy that included bartering and trading goods and selling surpluses in the market. The second era saw diversified commercial family farming, with the sale of farm products, including livestock, to urban areas. The final stage was truck farming, which saw the raising of mostly fruits and vegetables. Throughout the earliest period the main barn types were the vernacular Dutch New World barn, the English-type barn, and the two-story Pennsylvania barn. Dutch and English barns were made of local indigenous hardwood, Pennsylvania barns of stone and brick.

Dutch barns were used to store a variety of grain crops in the large hayloft. The barn itself tended to be wider than long, with a threshing floor in the middle and a bay on either side. The bays were usually at ground level where hay would be placed to house the animals. Wagon doors were situated at both gable ends of the barn, with Dutch doors on either side allowing people access to the animals. Steep and sloping, the roofs allowed rain and snow to fall off easily. The barns faced south to avoid harsh weather. The Dutch barns were located wherever Dutch culture agriculture established itself, which was primarily along the Hackensack, Millstone, Raritan, Passaic, and Hudson rivers and their tributaries.

The English barn was found throughout the Jerseys. The basic English barn had three bays—two side bays, one to house livestock, the other to store grain, and a threshing floor, with the wagon doors on the long sides of the barn. The dimensions of most English barns were sixty feet in length by thirty feet in width. The center portion was used for threshing. One of the keys to the English barn in North America was the swing beam that allowed for a large storage area for fodder in the loft.

The Pennsylvania barn was built in New Jersey’s southern Piedmont throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It was a two-floor banked barn that allowed wagons access to both levels. Animals were kept on the first level. The second level contained the threshing floor and storage space for grain. It also had a floor bay extending over the animal yard. Some Pennsylvania-style barns in the nineteenth century eliminated the floor bay and did not build into land banks, instead constructing an earthen ramp to the second floor.

Old Dutch-type barn, Black wells Mills, 1931.

Around the time of the Civil War, English and Dutch barns started to hybridize and blend as newer barn technology, mass production techniques, specialized farming, and a changeover to truck and dairy farming led to the universal, modern barn with which we are familiar today. By the end of the nineteenth century barns became uniform in style, with metal sides, gable roofs, and occasionally silos; the form has continued to the present.

Barrier islands. The barrier islands protecting most of New Jersey’s 127-mile coastline are land masses risen from sandbars and shaped over several thousand years by the action of wind, storm surges, and currents. In the natural state their seaward sides are a wall of dunes stabilized by the root systems of grasses andother vegetation. Between every barrier island and the mainland lie bays and lagoons of varying sizes edged with salt marshes and mudflats. Tides and ocean currents form ever-shifting new sandbars offshore and in the inlets, occasionally causing a barrier island to join the mainland and become a peninsula, like Sandy Hook or Island Beach.

Barrington. 1.6-square-mile borough in Camden County. Incorporated out of Centre Township on April 17, 1917, Barrington is one of a number of towns of single-family homes that developed along White Horse Pike after the parallel Philadelphia and Atlantic City railways became operational in 1877. The original station name was Dentdale. One of the developers named the new community Barring-ton after his hometown of Great Barrington, Massachusetts. The population more than doubled after World War II, when homes were built on the remaining farms. The Edmund Scientific Company, an internationally known supplier of optical instruments, is located here. The Barrington Band, organized in 1913, first participated in the Philadelphia Mummers Parade in 1917 and is still going strong. For a few years in the 1940s Barrington had its own airport, where some returning servicemen learned to fly, supported by the GI Bill.

According to the 2000 census, the population of 7,084 was 92 percent white. In 2000 the median household income was $45,148.

Barton, Clara (b. Dec. 25, 1821; d. Apr. 12, 1912). Teacher, nurse, philanthropist, and founder of American Red Cross. Clarissa Har-lowe Barton was born in North Oxford, Massachusetts, the youngest child of a farming family. At age eighteen, she began a career as a schoolteacher. In 1850, to further her education, she enrolled in the Liberal Institute in Clinton, New York, and a year later, visiting a school friend in Hightstown, she resumed her teaching career in New Jersey. In 1852 she moved to a school in Bordentown. Because she disliked a system in which she had to bill students at the end of each term for her salary, she began a campaign to establish a free public school supported by the town. A popular teacher, Barton’s project enjoyed town wide support, and the school board built a larger school to accommodate the growing numbers of enthusiastic students eager for free education. Barton was disappointed, however, when the town insisted on hiring a male principal and then paid him a salary much higher than her own. She was also not pleased to be called his "female assistant.” In 1854 she found better-paid employment as a government clerk in Washington, D.C., but faced harassment from male colleagues. These early experiences of discrimination led Barton, a friend of Susan B. Anthony, to support the woman suffrage movement and other feminist causes.

Her efforts to aid a contingent of Massachusetts soldiers quartered in the capital on the eve of the Civil War led to a personal drive to collect food and medicine for the Union Army. By 1862 she was running supply lines to the Army of the Potomac throughout the battlefields of Virginia and Maryland. Transporting supplies and nursing the wounded, Barton often worked under fire and assisted at such bloody battles as Antietam and Fredericksburg. From 1866 to 1868, she gave public lectures about her experiences and became a popular speaker.

On a trip to Europe for her health, she learned about the International Committee of the RedCross, a relief organization that carried out the new Geneva Convention’s mandate for the humane treatment of wounded soldiers and prisoners. Impressed with Red Cross efforts during the Franco-Prussian War, Barton returned to America and, almost single-handedly, convinced Congress to ratify the Geneva Convention. By 1881 she had established an American Association of the Red Cross in Washington, D.C.

Matthew Brady, Clara Barton, c. 1865. Albumen print, 6 1/16 x 41/4 in.

As president of the Red Cross throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Barton personally directed relief efforts in both international and national arenas, introducing the practice of assisting natural disaster victims as well as those of war. During the Spanish-American War, the Red Cross was criticized for disorganization and financial mismanagement and Barton’s leadership was questioned. Under pressure from President Theodore Roosevelt and her own board of directors, she reluctantly resigned in 1904. Bitterly estranged from the Red Cross, Barton spent her later years living in Glen Echo, Maryland, where she continued philanthropic work and wrote her memoirs.

Basalt. Basalt is a very common volcanic rock composed largely of plagioclase feldspar and pyroxene. Three layers of basalt exposed as parallel ridges across northern New Jersey (the Watchung Mountains) are known as the Orange Mountain, Preakness, and Hook Mountain Formations in order of their relative age. Each of the three formations consists of multiple flows that extruded out of rifts that opened during the initial Jurassic stages of the opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The flows are part of a major continental flood basalt event that covered large portions of eastern North America and northwest Africa about 200 million years ago before they were separated. The individual flows in New Jersey are unusually thick (up to 450 feet).

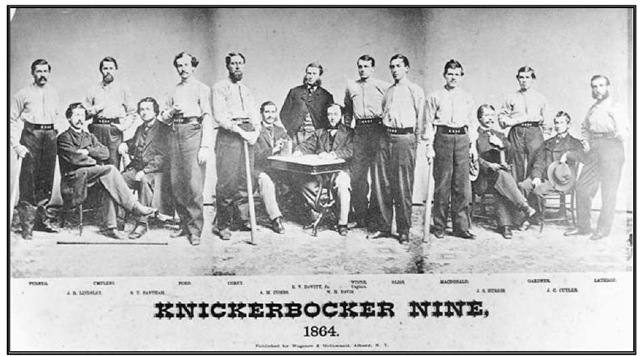

Baseball. Baseball as it is played today throughout the world began on June 19,1846, at the Elysian Fields in Hoboken. That day, Alexander Cartwright’s Knickerbockers and the New York Nine crossed the Hudson River to play the first game under new rules devised by Cartwright. Persistent tales that Abner Doubleday "invented” the game at Cooper-stown, New York, are patently false.

Several forms of organized baseball had been played since colonial times: a 1774 book published in London had a segment devoted to "Baseball.” Several varieties of the game were being played in the early 1840s. The June 1846 game in Hoboken clarified the game and codified the rules.

Most of those 1846 rules persist, such as the diamond-shaped field, the ninety-foot distance between the bases, nine-man teams with each player assigned to a definite spot on the field, formal lineups, innings of three outs each, outs made by throwing out or touching out offensive players, and the pitcher’s box placed within the diamond. The pitcher was only forty-five feet from the batter, however; that distance was increased to the present sixty feet, six inches, in 1893.

In an era when nearly all men worked as many as twelve hours a day, the Knickerbockers played every Tuesday and Thursday afternoon. They believed themselves socially superior and felt only "aristocrats”would ever play the game. Despite this attitude, the Knickerbockers sent out a complete description of their game rules to anyone who inquired.

By Civil War time, more than 150 teams played baseball in New Jersey as seniors, juniors, or "muffets” (the forerunner of Little Leagues). By 1865 many teams began paying players to perform before crowds of up to five thousand. Three members of the renowned Cincinnati Red Stockings, who barnstormed across the country in 1869 (winning fifty-nine straight games), were from New Jersey. Each received eight hundred dollars for the season.

The College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) emerged as New Jersey’s strongest team after three Brooklyn players enrolled in 1858, bringing their own bats and balls to the campus. In a show of strength, the Princeton college nine defeated three strong Brooklyn teams in a four-game swing through the area that was then the heart of baseball. No other team had ever accomplished that feat.

The two finest early New Jersey professionals were Mike "King” Kelly of Paterson and

The Knickerbocker Nine Baseball Club, 1864.

Billy "Sliding Billy” Hamilton of Newark. Kelly’s prowess made him the first player to earn five thousand dollars in a season. His base-stealing style prompted a song in his honor, "Slide, Kelly, Slide.” Hamilton, also flashy on the bases, stole 912 bases in his career (a mark that stood until 1978) and had a lifetime batting average of .344, eighth highest in major league history.

Two of the first African American players in high-level professional baseball were George Stovey, pitcher, and Fleetwood "Fleet” Walker, catcher. Both played in the 1880s with the Newark team in the old International League. Stovey won thirty games in 1887 and thirty-two games a year later. Walker went on to play for Toledo, a major professional team.

Nearly every community in New Jersey had a team by 1900. Most games were played on Saturday afternoons because of the long work week of most people. Companies in urban areas hired the best players to represent the firms on the field. Particularly strong were the Newark Westinghouse nine, the Doherty Silk Sox of Paterson, and the Michelin Tire Company team in Millville.

New Jersey had only one major league baseball team, the Newark Peps of the short lived Federal League. The Peps actually played in Harrison under the Newark name. Their wooden stadium, seating thirty thousand people, was built in seventeen days in 1914. The Federal League existed for only one year, and when it died in 1915, the Peps died as well.

New Jersey baseball historians believe the finest teams ever to play in New Jersey were the Newark Bears of the 1930s. In 1932 Jacob Ruppert, a New York beer baron and owner of the New York Yankees, bought the team and began sending fine prospects to Newark. The 1932 team won 109 games and lost only 59. Most of the players went on to major league stardom. The 1937 team initially showed little promise, but it caught fire and won 109 games, losing only 43 in the regular season. Twenty-eight of the thirty-three players on the roster became major leaguers.

College baseball began with the College of New Jersey team in the early 1860s, and, before the end of the nineteenth century, nearly every college or university had a team. High school baseball in New Jersey began in the late 1890s but did not become popular until about 1910, when the state had approximately a hundred secondary schools. Nearly every high school had a fully equipped team by 1930.

The high point for New Jersey baseball came in the 1930s, during a time of stifling economic depression and well before Little Leagues began. Sandlot teams, self-organized and self-governed, played everywhere—often as many as a hundred games in a season for an exceptional team. Most towns were members of adult "twilight" leagues, with games being played between six p.m. and the onset of darkness. Working men with high skills played in highly competitive weekend semipro leagues.

During World War II several young New Jersey women ventured to the Chicago area to play in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. The game was, in reality, fast-pitch softball, but intense competition for jobs promoted hard play, which made the games exciting and often inflicted severe injuries.

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 opened the way for full female participation in fast-paced softball. Trenton State College (now The College of New Jersey) was arguably the nation’s finest college fast-pitch softball team during the 1980s and 1990s. The same can be said at the high-school level for Whippany Park, whose softball teams had a seventy-six-game winning streak from 1989 to 1991. Its star, Toni Forunato, pitched 475 innings in three years, struck out 723 batters, pitched no-hitters, and won eighty games while losing only one.

For most players today, baseball consists of Little League—now open to both girls and boys—possibly high school or college play, and rarely a big league tryout. Baseball is no longer the great American game, at least in comparison with the 1930s, when it was a way of life. But the recent revival of minor league baseball in the new stadiums around the state demonstrates that interest in the game remains very much alive.

BASF. In 1861, Frederick Englehorn of Mannheim, Germany, founded a company to manufacture dyes from coal tar; his company specialized in indigo. Reestablished in 1865 as Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik, AG, BASF became one of the three largest German chemical companies. Later, as part of a cartel under I. G. Farben, BASF manufactured war materiel for the German Reich during World War II, which resulted in the destruction of 45 percent of its buildings by the Allies.

Restructured following the war, BASF became the world’s fourth-largest chemical company. BASF’s products include mineral oil, natural gas, plastics, intermediaries for synthetic fibers, nitrogen compounds, and dyes. Although BASF’s plan to launch operations in the United States was thwarted initially by protests in the 1970s, BASF started numerous joint ventures with U.S. companies during the 1980s. Then in 1994, the International Trade Zone in Mount Olive became the headquarters of North American operations for BASF AG, with over 105,000 employees.

BASF also manufactures agricultural products in West Windsor; polystyrene packaging in South Brunswick; auto paints and coatings in Belvidere; plastics in Washington, Warren County; and pharmaceuticals in Whippany. The company’s community efforts include donating land in Winslow Township to the New Jersey Natural Lands Trust. Klaus Peter Lobbe now heads BASF Corporation, which is BASF AG’s NAFTA region representative.