Auto theft. For many years, the rate of auto theft in New Jersey’s urban areas consistently ranked among the worst in the nation. This ranking reflects some of the realities of auto theft. Jersey City and Newark serve as entry ports for many of the vehicles that are imported into the United States. The primary economic reason for stealing a car is not for the car itself but for the resale value of the parts. While some of these parts are exported overseas, many are resold domestically in a thriving black market involving unscrupulous auto repair shops and consumers seeking cheaper deals on auto repairs.

The 2000 New Jersey Uniform Crime Report indicates that 72 percent of motor vehicle thefts cleared by arrest were committed by persons under twenty-five, the overwhelming majority of them being male. Of the 521 juveniles arrested for auto theft in 2000, 52 percent lived in the counties containing the six major urban areas: Camden City (Camden), Elizabeth (Union), Jersey City (Hudson), Newark (Essex), Paterson (Passaic), and Trenton (Mercer).

Prior to the 1990s auto theft was considered a low-priority offense because it was viewed as a relatively harmless, nonviolent, economic crime. This perception began to change when carjacking introduced an element of violence and fear. Also, stolen cars are often used to commit another offense or as a means of escape. Stolen vehicles are involved in police chases and contribute to motor vehicle collisions that result in death and injury. In addition, as cars became more expensive, the economic consequences increased. The cost of automobile insurance has become one of the most contentious issues in New Jersey. People have begun to see the impact of this crime in their increasing auto insurance premiums.

Avalon. 4.6-square-mile borough in Cape May County located on part of Seven Mile Island. When Aaron Leaming purchased Seven Mile Island in 1723 for $380, the land had little value. Named Leaming’s Beach, it was used for pasturing cattle, hunting game, and landing whales. In 1887 the Seven Mile Beach Company bought the land, built a hotel, and sold huge tracts to other developers. Two years later, hoping to ensure growth, the company gave the West Jersey Railroad a right-of-way the length of the island, a decisive factor in the island’s development. During summer weekends trains brought four to five thousand people to enjoy the beach, picnic, and perhaps purchase a lot.

Avalon separated from Middle Township and incorporated in 1891. A lifesaving station was established in 1894 and a boardwalk was constructed in the early 1900s; in 1912 the first school was built. In 1911 Gov. Woodrow Wilson opened bridges on Stone Harbor Boulevard to link the island with the mainland. In 1912 service from Cape May Courthouse was provided by the Reading line across a bridge at Ninety-sixth Street. Today, as in the past, tourism is Avalon’s primary industry.

The 2000 population of 2,143 was 99 percent white. The median household income was $59,196, according to the 2000 census. For complete census figures, see chart, 129.

Aviation Hall of Fame and Museum of New Jersey. Founded in 1972, the Aviation Hall of Fame and Museum (AHOF) preserves New Jersey’s two-centuries-old aeronautical history and honors the men and women who created that special heritage. The AHOF was the first state aviation hall of fame in America. It is the repository of biographical histories and photographs of the Garden State’s pilots, astronauts, inventors, engineers, mechanics, writers, artists, executives, and corporations. The bronze plaques of 122 New Jersey aviation pioneers hang in the AHOF, housed in a modern museum at Teter-boro Airport. The museum’s galleries are dedicated to airports, the military, space flight, airmail, lighter-than-air craft, aerobatic pilots, women aviators, and early fliers. There is also a library.

Bernice "Bee” Falk Haydu, wearing open-cockpit aircraft gear, during WASP training, 1944.

Aviation industry. The New Jersey aircraft industry began as part of the industrial buildup in support of World War I. There were failed attempts as early as 1907, but the war economy produced the environment for the aviation industry to emerge. The state’s first successful aircraft plant was the Aero-marine Plane and Motor Corporation at Key-port, which made hydroplane trainers and a flying boat for the navy. Another plant, the Standard Aero Company, began production of military aircraft in 1916 in Plainfield and later in Linden. Both companies failed to survive the cut in government orders and public sale of war surplus aircraft and engines following the 1918 armistice. Anthony H. G. Fokker, famed for his World War I German aircraft, founded the Fokker Aircraft Corporation in 1924 at Teterboro. Fokker designed and built aircraft for emerging airlines and other businesses for the remainder of the 1920s, but the company collapsed during the Great Depression. Wright-Martin Aircraft Corporation, later known as Wright Aeronautical Company, was formed in 1916 and began building engines for the military in New Brunswick. Wright survived the fate of other failed companies by acquiring the rights to a successful air-cooled engine and improving upon it. Wright became a major supplier of civilian and military aircraft engines and later merged with the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Corporation to become the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. In World War II, Curtiss-Wright produced engines for a great variety of military aircraft, including the B-17, B-29, A-20, TBM, and SB2C. The Curtiss-Wright Propeller Division at Caldwell produced one-fifth of all of the propellers made in the United States during the war.

The General Motors Corporation also played a big part in the New Jersey aircraft industry. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government ordered the curtailment of all civilian automobile production to conserve materials for the war. This left the modern General Motors plants in Linden and West Trenton idle with no equipment or facilities that could be easily converted to war production. Company representatives visited the Navy Department in an attempt to secure a contract for aircraft components. They were granted contracts for fighter planes and torpedo bombers and formed the Eastern Aircraft Division of the General Motors Corporation. The Linden plant produced Wildcat fighters and West Trenton, Tarrytown, New York, and Baltimore, Maryland, worked together to build Avenger dive bombers, with final assembly in West Trenton. Another plant, in Bloom-field, made the hydraulic lines, cables, wires, and electrical components for both aircraft. Before production could begin, the Linden and West Trenton plants had to be stripped of tons of automobile-assembly equipment. The buildings were modified, and aircraft-assembly equipment and fixtures were constructed and installed. Airfields and hangars also had to be constructed adjacent to the plants in order to test the new aircraft. After a slow start production got under way, and Eastern Aircraft Division produced a total of 13,232 aircraft, which went to every theater of the war, and some remained in service until the 1950s. The conclusion of the war brought an end to the need for additional combat aircraft. Military agencies quickly canceled contracts for thousands of aircraft and aircraft engines. The Eastern Aircraft plants, no longer needed for Avenger and Wildcat production, soon resumed production of General Motors automobiles.

Aviation research. New Jersey has been a center for aviation research for the military and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) from the 1930s to the present. Some of the earliest aviation research and development in the state was conducted at Lakehurst, where the navy acquired 1,700 acres of land once used by the army. The new facility was used to develop America’s dirigible program. A huge hanger was constructed and the navy’s first dirigible, the USS Shenandoah, was assembled within. For the next decade, Lakehurst pioneered the development of the navy’s dirigibles. A number of blimps also operated from the station. At the same time, the first parachute school opened at Lakehurst. The school not only provided training in operation and use of parachutes, but also testing and development.

The USS Shenandoah was followed by the USS Los Angeles and later the USS Akron and USS Macon. The Akron and Macon were designed to carry, launch, and recover fighter aircraft. In April 1933, the Akron was lost during a thunderstorm off Barnegat Light; the Macon was lost in 1935, when the ship fell into the Pacific Ocean off the California coast. These two tragic events brought an end to the navy’s attempt to develop dirigibles. The blimps and lighter-than-air research remained at Lakehurst until 1962. Today, the Naval Air Systems Command at Lakehurst provides expertise, testing, and research in areas most often associated with aircraft carriers. Areas of expertise include catapults, jet blast deflectors, arresting gear, visual landing aids, handling equipment, servicing equipment, and propulsion/avionics support equipment.

In 1946 the U.S. Navy Development Squadron 3 (VX-3) moved to Lakehurst and began testing, research, and training with Sikorsky and Bell helicopters. It moved to Naval Air Station Atlantic City in 1948, where the squadron began research and training with fighter aircraft. For nearly ten years, VX-3 tested aircraft, systems, and munitions at Atlantic City. It continued its work at Quonset Point, Rhode Island, upon the decommissioning of NAS Atlantic City in 1958. In the same year, the National Aviation Facilities Experiment Center (NAFEC) was established as a research and development center for the FAA in Atlantic City, selected because of its wide range of weather conditions and location close to both the Northeast corridor and the open space over the ocean. NAFEC used the former navy facilities until 1980, when it constructed a new $50-million facility and moved to another part of Atlantic City Airport. At that time it became the Federal Aviation Technical Center, but was renamed the FAA William J. Hughes Technical Center in 1996. The center is the national scientific test base for FAA research, development, and acquisition programs. The facility tests and evaluates air traffic control, communications, navigation, aircraft, and airport security. It also develops new equipment and software and recommends modifications to existing procedures and systems.

Avon-by-the-Sea. 0.4-square-mile borough located between the Shark River and Sylvan Lake in Monmouth County. Avon-by-the-Sea was originally named Key East in 1879, when Edward Batchelor purchased three hundred acres in Neptune Township for a seaside development scheme. The community’s street plan was based on a strict grid pattern, with six eighty-foot-wide tree-lined avenues running east to west.

Key East was patterned after the religious community of Ocean Grove, with a Christian Philosophy Summer School run by the American Institute, a Baptist Seaside Assembly, and a summer home for crippled orphans managed by the Episcopal Church. In 1900 Key East seceded from Neptune Township to become an independent borough named Avon-by-the-Sea. The building of grand hotels and open-porch homes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries attests to Avon-by-the-Sea’s appeal as a summer beach resort. The U.S. Coast Guard Shark River Boat Station is located in the borough on the Shark River.

The borough has a mix of 1,381 housing units, with 298 (or 24.8 percent) of them available for seasonal use. In 2000, the population of 2,244 was 97 percent white. The median household income in 2000 was $60,192. For complete census figures, see chart, 129.

Aylsworth, Jonas Walter (b. 1868; d. 1916). Chemist and manufacturer. Jonas Aylsworth, born in Attica, Indiana, attended Purdue University for one year before joining Thomas Edison’s laboratory staff as a chemist in 1887. He left Edison’s direct employ in 1894 but continued to work under contract on a number of Edison’s inventions. Aylsworth’s most important contributions came in the development of the Edison phonograph record technology. In the late 1880s he developed the standard wax record, around 1900 devised, with Walter Miller, a process for manufacturing molded records, and around 1910 created Condensite, the first interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) material, which was used in Edison disc records and many other molded plastic products.

Babe Ruth Baseball. This premier amateur baseball program for thirteen- to fifteen-year-olds was founded in Yardville in 1951. It began in February 1951 as a local organization called the Little-Bigger League (recognizing that the Little League, founded in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, in 1939, graduated its players at age twelve). The first games were played in Yardville and Trenton on May 14, 1951. Later that summer, the organization established a nationwide Little-Bigger League with its leaders as the first national board. The league’s first nationwide championship, or "world series,” was held in Trenton in August 1952. Before the start of the 1954 season, the organization changed its name to Babe Ruth Baseball, Inc., to honor George Herman "Babe” Ruth, America’s greatest baseball player, who had died in 1948.

Babe Ruth Baseball has grown steadily and now operates throughout North America and Europe. It had more than a million players worldwide in 2002. A twelve-and-younger division, now known as the Cal Ripken Division in honor of the former Baltimore Orioles shortstop, was added in 1982. Trenton teams won the Babe Ruth World Series in 1956 and 1962, and a Ewing team did so in 1970.

Baby M case. As the first major trial to address surrogate motherhood and reproductive-technology questions, the Baby M case was the focus of national media attention in 1987 and 1988. At issue was custody of so-called Baby M (Melissa Stern), the biological child of William Stern, a biochemist, and Mary Beth Whitehead, a housewife married to a sanitation worker. Baby M was conceived through artificial insemination using Stern’s sperm and Whitehead’s egg after they signed a contract stipulating that Whitehead would terminate her parental rights and turn the child over to Stern and his wife, Elizabeth, a pediatrician. Whitehead was to be paid $10,000 upon surrendering the infant.

Soon after the birth, Whitehead decided that she could not give up the child, whom she had named Sara. Drama ensued as first Whitehead, then the Sterns, then Whitehead had custody of the child. Whitehead then fled with the baby to Florida for four months, while the Sterns took legal action to enforce the surrogacy contract and were awarded temporary custody. Whitehead was given limited visitation rights. A trial followed, and a lower-court judge ruled in the Sterns’ favor, terminating Mrs. Whitehead’s parental rights and granting custody to Stern. Mrs. Stern was allowed to adopt the baby and become her legal mother.

Many opposed the ruling, arguing on Whitehead’s behalf that involuntary termination of parental rights was legal only in cases of abandonment or abuse. Others noted inherent socioeconomic bias, since the well-off Sterns had better resources to fight in court and were able to provide an arguably "better” life for the baby. Critics worried that contractual surrogacy would create a "breeder class” of lower-income women.

On appeal the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled seven to zero to invalidate the surrogacy contract, calling it "baby-selling.” Whitehead’s parental rights were restored and Mrs. Stern’s adoption of the baby annulled. The court granted Mr. Stern custody to spare the baby further disruption, but allowed Whitehead expanded visitation rights.

Bacon, Henry (b. Nov. 28,1866; d. Feb. 14, 1924). Architect. Henry Bacon, son of Henry and Elizabeth Kelton Bacon, was born in Watseka, Illinois, in 1866 and married Laura Florence Calvert in 1893. He trained at the architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White from 1888 to 1896, studied in Europe from 1889 to 1891, and established his own firm in 1897. A devotee of the classical vocabulary for public architecture, Bacon was most notably the designer of the simple yet majestic Lincoln Memorial (1922) in Washington, D.C. He also designed humbler municipal buildings in New Jersey including the Public Library (c. 1900) in Jersey City and the Dansforth Memorial Public Library (1906) in Paterson.

Bakelite. In 1904 a Belgian scientist and university lecturer working in the United States, Leo HenrikBaekeland (1863-1944), succeeded in producing a synthetic shellac by combining formaldehyde, a wood alcohol used by morticians as embalming fluid, and phenol, a coal-tar distillate used as a turpentine substitute. Called "Bakelite,” it was the first of the thermosetting plastics—it could be molded into any shape but, after it had solidified, it could not be melted again. Once hard, it could be machined into any shape and it was waterproof and resistant to heat, cold, and acid.

Baekeland was the first to put together a series of small molecules in a chain to form a commercially useful artificial substance. On February 5,1909, at the Chemist’s Club in New York, Baekeland introduced his new product, calling it the "Material of a Thousand Uses.” One of its first uses was in the manufacture of billiard balls, replacing rare and expensive ivory. The material became the ideal component for the emerging electronics industry in need of new kinds of insulators. Bakelite was quickly used to form telephones, airplane propellers, electrical plugs and sockets, pot handles, toasters, cheap radios, electronic ignitions for automobiles, and, eventually, heat shields for spaceships. Baekeland’s work unleashed a flurry of chemical research into synthetic material, work that would produce celluloid, nylon, and polyvinyl chloride.

This work had been bankrolled by an earlier discovery. In the 1890s Baekeland had invented Velox, an improved photographic paper that freed photographers from having to use sunlight for developing images. With Velox, they couldrely on artificial light. George Eastman, whose camera and developing services would make photography an almost everyday activity, bought full rights to Velox from Baekeland for the then astonishing sum of $1 million.

Soon after he had presented Bakelite to a worldwide audience, a flash fire consumed Baekeland’s home garage, torching most of his adjacent laboratory. When he learned that the Perth Amboy Chemical Works in Perth Amboy had space to rent, he relocated the General Bakelite Company to safer quarters. Bakelite also helped Heyden Chemical Works to thrive in Garfield, where workers eventually perfected a new process for making formaldehyde.

Bakelite products dominated the plastics industry throughout the 1920s. The company bought the old Swayze Farm in Bound Brook in 1930, and in 1932 merged full operations in the new plant, which was turning out more than 30 million tons of finished product annually. By 1936 the editors of Fortune magazine had crowned Bakelite the "King of Plastics.”

Control of Bakelite passed to Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation in 1939. Bakelite’s use continued during World War II, including use in the design of the atomic bomb. But the company also developed a material it called Vinylite. Going beyond military uses, the material grew in less than a decade into an immense postwar enterprise dedicated to making swimming pools, beach balls, raincoats, shower curtains, and automobile upholstery.

Baker, Hobart "Hobey" Amory Hare (b. Jan. 15,1892; d. Dec. 21,1918). Athlete. Considered the greatest U.S. hockey player of his era, Hobey Baker was born in Wissahickon, Pennsylvania. He starred at the rover position for Princeton (1911-1914), where he captained the team to two intercollegiate championships. He was also an all-American football player. After graduation, Baker played amateur hockey for the Saint Nicholas Skating Club in New York City and led the team to a Ross Cup victory over Montreal. While serving as a military pilot, Baker died in a crash at Toul, France, during a test flight one month after the end of World War I. In 1922 Princeton dedicated the Hobey Baker Arena for ice hockey, and the Hobey Baker Memorial Award is given annually to the nation’s best college hockey player.

Baldanzi, George (b. Jan. 23,1907; d. Apr. 16,1972). Labor union leader. At the age of sixteen, Baldanzi began working as a coal miner alongside his father. After moving to Paterson, he became an active textile unionist and organized the Dyers’ Federation, of which he bald eagle. Haliaeetus leucocephalus, a member of the Accipitridae family, is among New Jersey’s largest birds, with a wingspan between 6.5 and 8 feet. Adults have a brown body and wings, gaining their characteristic white head and tail at five years of age.

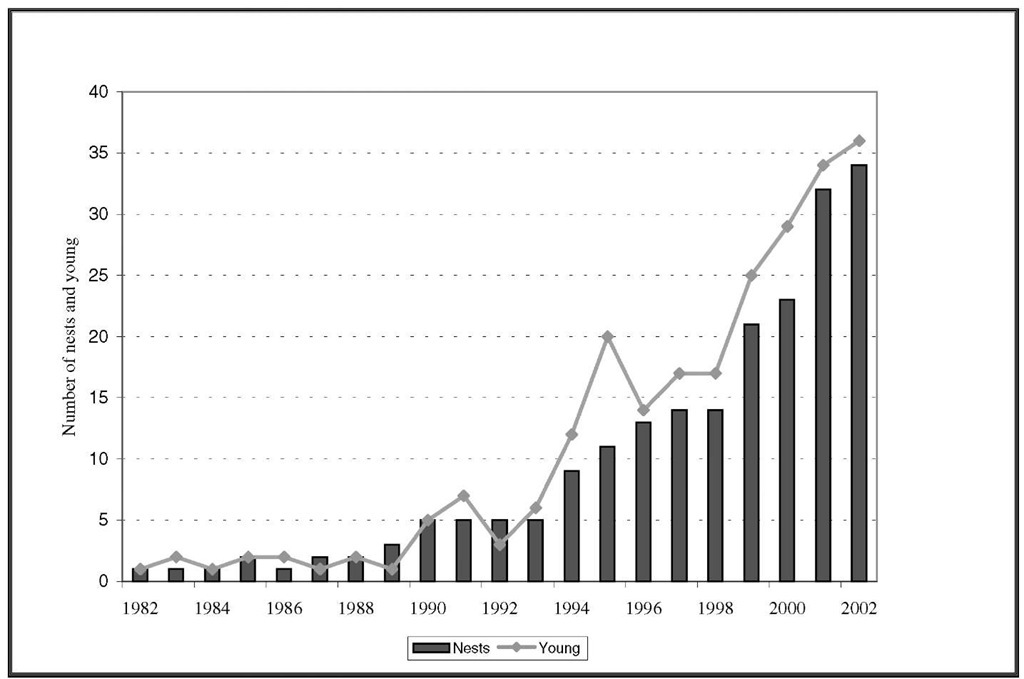

The bald eagle population in New Jersey declined to just one nest due to contamination by DDT in the 1950s. As a result of recovery efforts that included habitat protection and release of young eagles from Canada, the population has rebounded to a new high of 34 pairs in 2002. Biologists continue to monitor threats such as habitat destruction and environmental contaminants.

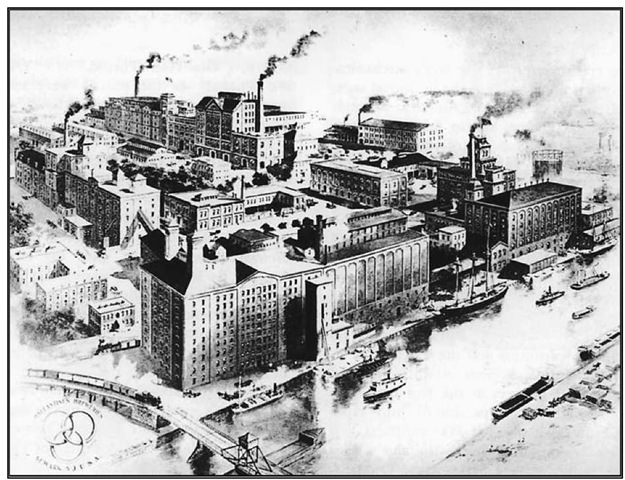

Ballantine, Peter (b. Nov. 16,1791; d. Jan. 23, 1883). Brewer. Born in Ayrshire, Scotland, Peter Ballantine immigrated to Albany, New York, in 1820 and spent ten years learning the brewery business. He married Julia Wilson in 1830; they had three sons. Ballantine ran a brewery in Albany for ten years before relocating to Newark. In partnership with Erastus Patterson, he rented a brewery on High Street from Gen. John R. Cumming. In 1850 he opened a large facility, noted for its ale, on the Passaic River. By the 1870s Peter S. Ballantine & Sons was the fourth largest brewery in the country.

Ballantine Brewery, Newark, 1905.

Ballantine House. Built in 1885 for beer brewer John Holme Ballantine and his wife, Jeannette Boyd Ballantine, the twenty-three-room Ballantine House is the only restored urban mansion in New Jersey open to the public. Designed by John Edward Harney of New York City and Newburgh, New York, the house combines a Renaissance exterior with an interior featuring rich Renaissance, Colonial Revival, and Aesthetic movement woodwork, wall coverings, and furnishings. Bought by the Newark Museum in 1937, it was restored in 1976 and in 1994, and presently serves as the decorative arts wing for the museum.