Ute (Yut), roughly 11 autonomous Great Basin bands. In the eighteenth century, eastern bands included the Uncompahgre (or Tabeguache), Yampa and Parusanuch (or White River Band), Mouache, Capote, and Weeminuche, and western bands included the Uintah, Timpanogots, Pahvant, Sanpits, and Moanunts. The word "Utah" is of Spanish derivation, probably borrowed originally from an Indian word. Their self-designation was Nunt’z, "the People."

Location Aboriginally, Utes lived in most of present-day Utah, except the far western, northern, and southern parts; Colorado west of and including the eastern slopes of the Rockies; and extreme northern New Mexico. Today, the three Ute reservations are in southwest Colorado, the Four Corners area, and north-central Utah.

Population From roughly 8,000 in the early nineteenth century, the Utes declined to about 1,800 in 1920. In 1990 approximately 5,000 lived on reservations, and roughly another 2,800 lived in cities and towns.

Language With Southern Paiute, Ute is a member of the southern Numic (Shoshonean) division of the Uto-Aztecan language family. All dialects were mutually intelligible.

Historical Information

History The Utes and their ancestors have been in the Great Basin for as many as 10,000 years. They lived along Arizona’s Gila River from about 3000 B.C.E. to about 500 B.C.E. At that time, a group of them began migrating north toward Utah, growing a high-altitude variety of corn that had been developed in Mexico. This group, who grew corn, beans, and squash and also hunted and gathered food, is known as the Sevier Complex. Another, related group of people, known as the Fremont Complex, lived to the northeast.

Many Utes came to Washington in 1868 to discuss the creation of the tribe’s first two reservations. Chief Ouray is seated to the right of an unidentified man. The U.S. government considered Ouray "head chief of the Utes," paid him an annual salary, and supplied him with expensive goods.

In time, Fremont people migrated into western Colorado. When a drought struck the Great Basin in the thirteenth century, the Fremont people moved into Colorado’s San Luis Valley, where they later became known as the Utes. They became one of the first mounted Indian peoples when escaped Spanish captives brought horses home in the mid-seventeenth century. Communal buffalo hunts began shortly thereafter. Mounted warriors brought more protection, and larger camps meant more centralized government and more powerful leaders as well as a rising standard of living. Utes also facilitated the spread of the horse to peoples of the Great Plains.

Southern and eastern Ute bands raided New Mexico Indians and hunted buffalo on the Plains during the seventeenth into the nineteenth centuries. Utes also raided Western Shoshones and Southern Paiutes for slaves (mostly women and children), whom they sold to the Spanish. Moreover, they were forced to defend some hunting territory against the Comanche (formerly an ally) and other Plains tribes around that time. As a result of relentless Comanche attacks, the Southern Utes were prevented from developing fully on the Plains. Driven back into the mountains, they lost power and prestige, and the northern bands, enjoying a more peaceful and prosperous life, increased in importance.

A Spanish expedition in 1776 was the first of a line of non-native explorers, trappers, traders, slavers, and miners. Non-natives established a settlement in Colorado in 1851, and a U.S. fort (Fort Massachusetts) was built the following year to protect that settlement. Utes considered non-native livestock grazing on their (former) land fair game. In the midst of growing conflicts, treaties (which remained unratified) were negotiated in the mid-1850s.

The flood of miners that followed the 1858 Rockies gold strikes overwhelmed the eastern Utes. At the same time, Utes were allied with the Americans and Mexicans against the Navajo. Mormons, fighting the western Utes for land from late 1840s on, had succeeded by the mid-1870s in confining them to about 9 percent of their aboriginal territory. The United States created the Uintah Reservation in 1861 on land the Mormons did not want. They made most Utah Utes, whose population had been decimated, settle there in 1864.

In 1863, some eastern bands improperly signed a treaty ceding all bands’ Colorado mountain lands. Five years later, the eastern Utes, under Chief Ouray, agreed to move west of the continental divide provided about 15 million acres was reserved for them. Soon, however, gold discoveries in the San Juan Mountains wrecked the deal, and the Utes were forced to cede an additional 3.4 million acres in 1873 (most of the remainder was taken in 1880). The U.S. government considered Ouray "head chief of the Utes," paid him an annual salary, and supplied him with expensive goods.

The Southern Ute Reservation was established on the Colorado-New Mexico border in 1877. At that time, the Mouache and Capote Bands settled there, merged to form the Southern Ute tribe, and took up agriculture. Resisting pressure to farm, the Weeminuche, calling themselves the Ute Mountain tribe, began raising cattle in the western part of the Southern Ute Reservation (the part later called the Ute Mountain Reservation).

In the late 1870s, a new Indian agent tried to force the White River Utes to give up their traditional way of life and "become civilized" by setting up a cooperative farming community. His methods included starvation, the destruction of Ute ponies, and encouraging the government to move against them militarily. When the soldiers arrived, the Indians made a defensive stand and a fight broke out, resulting in deaths on both sides (including Agent Nathan Meeker and U.S. Army Commander Thomas Thornburgh). Chief Ouray helped prevent a general war over this affair. The engagement was subsequently called by whites the Thornburgh "ambush" and the Meeker "massacre" and led directly to the eviction of the White River people from Colorado.

By 1881, the other eastern bands had all been forced from Colorado (except for the small Southern and Mountain Ute Reservations), and the other eight bands, later known as the Northern Ute, were assigned to the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in northern Utah (the Uintah Reservation was expanded in 1882 to include the removed Weeminuche Band).

Government attempts to force the grazing-oriented Ute to farm met with little success, owing in part to a lack of access to capital and markets and in part to unfavorable soil and climate. Irrigation projects begun early in the twentieth century mainly benefited non-Indians who leased, purchased, or otherwise occupied Ute land. The government also withheld rations in an effort to force reservation Utes to send their children to boarding school. During the mid-1880s, almost half of the Ute children at boarding schools in Albuquerque died. In 1911, the Ute Mountain Utes increased their acreage while ceding land that became Mesa Verde National Park.

The last traditional Weeminuche chief, Jack House, assumed his office in 1936 and died in 1971. Buckskin Charley led the Southern Utes from Ouray’s death in 1880 until his own in 1936. His son, Antonio Buck, became the first Southern Ute tribal chair. During the 1920s and 1930s, Mountain Utes formed clubs to promote leadership and other skills. Disease remained a major killer as late as the 1940s.

By 1934, the eastern Utes controlled about .001 percent of their aboriginal lands. In 1950, the Confederated Ute Tribes (Northern, Southern, and Mountain) received $31 million in land claims settlements. During the 1950s, Ute Mountain people began to assume greater control over their own money, and mineral leases provided real tribal income. Funds were expended on a per capita basis and invested in a number of enterprises, mostly tourist related. The 1960s brought federal housing programs and more land claims money, but the effectiveness of tribal leadership declined considerably. A group of mixed bloods, called the Affiliated Ute Citizens, were legally separated from the Northern Utes in 1954.

Religion Utes believed that supernatural power was located within all living things. Curing and weather shamans, both men and women, derived additional power from dreams. A few shamans, influenced by Plains culture, undertook vision quests.

One of the oldest of Ute ceremonies, the ten-day Bear Dance was a welcome to spring. Bear is a mythological figure who provides leadership, wisdom, and strength. Perhaps originally a hunting ritual, the dance, directed by a dance chief and his assistants, signaled a time for courtship and the renewal of social ties. It was also related to the end of the girls’ puberty ceremony. An all-male orchestra played musical rasps to accompany dancers. The host band sponsored feasting, dancing, gambling, games, and horse racing.

The Sun Dance, of Plains origin, was held in midsummer.

Government Before the mid-seventeenth century, small Ute hunting and gathering groups were composed of extended families, with older members in charge. There may also have been some band organization for fall activities such as trading and hunting buffalo.

With the advent of horses, band structure strengthened to facilitate buffalo hunting, raiding, and defense. Each band now had its own chief, or headman, who solicited advice from constituent group leaders. By the eighteenth century, the autonomous bands came together regularly for tribal activities. Each band retained its chief and council, and within the bands, family groups retained their own leadership.

Customs Western Utes were culturally similar to the Paiutes and Shoshones, whereas eastern Utes adopted many Plains traits. The southeastern Utes, in turn, were influenced by the Pueblos and the Jicarilla Apache. Resource areas were owned communally. Games included shinny (women), hoop-and-pole, and dice.

People chose their own spouses with some parental input. Divorce was easy and common. In general, men could have multiple wives. There were various taboos and food restrictions during and immediately after pregnancy for both men and women. Minor rituals were meant to ensure a child’s industriousness. Although children were welcomed, twins were considered an unlucky sign, and one or both were often allowed to die. Naming might take place any time, and names were not fixed for life. Nicknames were common.

A menstruating woman was secluded and observed several behavioral restrictions, including the common one of not being allowed to scratch herself with her own hands. There were few puberty customs per se, although girls sometimes danced the Bear Dance, and boys could not eat their first kill. Corpses were wrapped in their best clothes and buried in rock crevices, heads to the east. Their possessions were destroyed (or occasionally given away), and their horses were killed or had their hair cut.

Dwellings The western Utes lived year-round in domed willow houses. Weeminuches used them only in summer, and all groups also used brush and conical pole-frame shelters 10-15 feet in diameter, covered with juniper bark or tule. Sweat houses were of similar construction and heated with hot rocks. In the east, after the seventeenth century, people lived in buffalo (or elk) skin tipis, some of which were up to 17 feet high.

Diet Bands generally regrouped into families to hunt and gather during spring and summer. Important plant foods included seeds, pine nuts, yampa, berries, and yucca. Some southeastern people planted corn in the late prehistoric period. Some groups burned areas to encourage the growth of wild tobacco.

Buffalo were native to the entire area and were important even before the horse. Other important animal foods included elk, antelope (stalked or driven over cliffs), rabbit (hunted with throwing sticks or communally driven into nets), deer, bear, beaver, fowl, and sage hens. Meat was eaten fresh, sun dried, or smoked. Coyote, wolf, and bobcat were hunted for their fur only.

Other important foods included crickets, grasshoppers, and locusts (dried with berries in cake form). Some western groups ate lizards and reptiles.

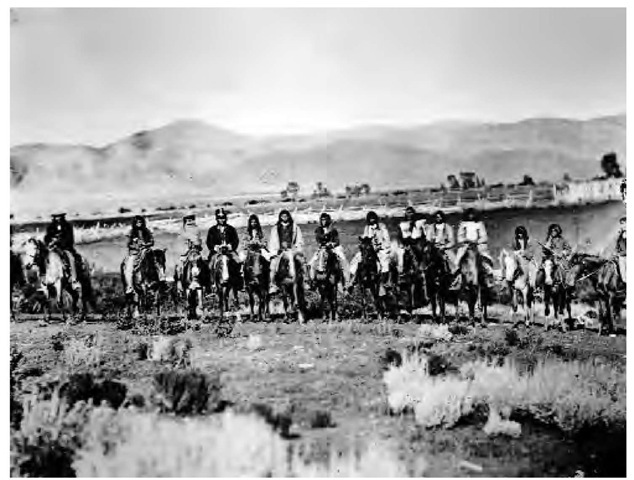

A Ute camp near Denver, Colorado.

Some bands also fished, especially in the west, using weirs, nets, basket traps, bow and arrow, and harpoons. Important fish included cutthroat trout, whitefish, chubs, and suckers.

Key Technology Musical instruments included flutes, rasps, and drums. Later prehistoric eastern groups obtained shelter, food, clothing, glue, containers, tools, bow strings, and more from the buffalo. Baskets, often made of willow and squawbush twigs, were used for a variety of purposes, especially in seed and berry gathering and preparation. Wood, stone, and horn were other common raw materials. People made cedar, chokecherry, or sheep horn bows, flint knives, and coiled pottery, mostly in the west. They wove tule sleeping mats and made cordage of various barks and plant fibers.

Trade Some southeastern bands traded at Taos and Pecos, perhaps exchanging meat and buckskin for agricultural products. Utes traded with the Spanish when they were not at war. They also acquired blankets and other items from the Navajo for buckskins and buffalo parts.

Notable Arts Fine and performing arts included music, especially singing and drumming; basket making; leather tanning (by women); rock art; and assorted art objects made from materials such as stone, wood, and clay.

Transportation Dogs pulled small travois before horses arrived in the region. Later, goods were moved on full-sized horse-pulled travois made from tipi poles. Winter hunters wore snowshoes, and some western groups used tule rafts or balsas.

Dress Eastern groups wore tanned buckskin clothing. Shirts were plain before increased contact with Plains groups added beads, fringe, and other designs. Twined sagebrush bark was the preferred material in the west. Blankets were made especially of rabbit and buffalo (especially in the east). Men protected their eyes against the sun with rawhide eye shields. They also wore beaver or weasel caps, and both sexes wore hard-sole moccasins over sagebrush socks in winter. Personal decoration included face painting (mostly for special occasions) tattooing, ear ornaments, and necklaces.

War and Weapons Before the horse, warfare was generally defensive in nature. Utes became mounted raiders in the late seventeenth century. Their usual targets were Pueblo, Southern Paiute, and Western Shoshone Indians. Weapons included a three- to four-foot bow (chokecherry, mountain mahogany, or mountain sheep horn was preferred) and arrows. Eastern Utes also used spears as well as buffalo-skin shields.

Some bands were allied with the Jicarilla Apache and the Comanche against both the Spanish and the Pueblos. Utes had generally poor relations with the Northern and Eastern Shoshone, although they were generally friendly with the Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute, especially before they began raiding these groups for slaves in the eighteenth century. Navajos were alternately allies and enemies. Eastern Utes observed ceremonies before and after raids.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Southern Ute Reservation is located in Archuleta, La Plata, and Montezuma Counties, Colorado. Established in 1873, it contains 310,002 acres. The 1990 Indians population was 1,044. A constitution adopted in 1936 provides for an elected tribal council.

The Uintah and Ouray Reservation is located in Carbon, Duchesne, Grand, Uintah, Utah, and Wasatch Counties, Utah. Founded in 1863, it contains 1,021,558 acres and had a 1990 Indian population of 2,647. It is governed by a business council.

The Ute Mountain Reservation, including the White Mesa Community, is in La Plata and Montezuma Counties, Colorado; San Juan County, New Mexico; and San Juan County, Utah. Created in 1873, it contains 447,850 acres. The 1990 Indians population was 1,262. A 1940 constitution provides for a tribal council.

Economy Important economic activities include oil and gas leases (all Ute reservations are members of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes), stock raising (Ute Mountain and Uintah and Ouray), some timber sales, interest on tribal funds, tribal and government agencies and programs, and tourism, especially on the Southern Ute and Uintah and Ouray Reservations. The Southern Utes are planning a casino and gambling complex. They have also purchased and operate natural gas wells.

The Ute Mountain high-stakes casino joins a bingo hall and pottery cooperative as important economic activities. Ute Mountain has also been able to restore some of its some year-round hunting rights and to negotiate model mineral leases, including provisions for job training. The Ute Mountain Tribal Park features Anasazi ruins. On the Southern Ute Reservation, the Sky Ute Convention Center has had trouble showing a profit. Up to one-half of Utes work for the tribal or federal government. Unemployment remains high on all Ute reservations, and household incomes remain well below those of neighboring non-natives.

Utes became mounted raiders in the late seventeenth century. Before the advent of the horse, warfare was generally defensive in nature.

Legal Status The Southern Ute Indian Tribe, the Ute Mountain Tribe, and the Ute Indian Tribe (of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation) are federally recognized tribal entities.

Daily Life The Ute language is still widely spoken, although less so among the Southern Ute and among young people in general. There are annual performances of the Bear and Sun Dances. Most housing on all reservations is relatively modern and adequate, although it is considered insufficient on the Southern Ute Reservation. The Southern Ute Reservation also holds a fair and a rodeo and features a newspaper, a library, and a Head Start program. It is the most acculturated of the three communities.

All tribes have scholarship programs for college-bound young people. The White Mesa people at Ute Mountain have become mixed with Navajos and Paiutes. Water there has been contaminated by nearby uranium mills. Most White Mesa people are Mormons. At Ute Mountain, life expectancy remains below 40 years, and alcoholism rates may approach 80 percent. Job discrimination remains a formidable obstacle to employment. Basketry and beadwork remain important artistic activities.

The Animas-La Plata water settlement may mean considerable additional water resources for drinking and possibly farming for the Southern and Mountain Utes. The Native American Church is active among the Southern and Mountain Utes. Factionalism based on tribal membership requirements and deep-seated political disputes, many based on government policy, still threatens the tribes. The quasi-official Affiliated Ute Citizens, with low blood quantums, remain ineligible for most tribal benefits.