Tlingit, meaning "human beings," is taken from the group’s name for themselves. The Coastal Tlingit were a "nationality" of three main groups—Gulf Coast, Northern, and Southern—united by a common language and customs. The Interior Tlingit have never considered themselves a cohesive tribe.

Of the three major groups of coastal Tlingits, the Gulf Coast group included the Hoonah of Lituya Bay; the Dry Bay people at the mouth of the Alsek River, who were established in the eighteenth century by a conglomeration of Tlingits and Athapaskans; and the Yakutat, who were composed of Eyak speakers from the Italio River to Icy Bay. In 1910 the Yakutat merged with the Dry Bay people. Northern Tlingits included the Hoonah on the north shore of Cross Sound, the Chilkat-Chilkoot, Auk, and Taku; the Sumdum on the mainland; and the Sitka and Huntsnuwu, or Angoon, on the outer islands and coasts. The Southern Tlingit included the Kake, Kuiu, Henya, and Klawak on the islands and the Stikine or Wrangell, Tongass, and Sanya or Cape Fox along the mainland and sheltered waters.

Location Coastal Tlingit groups lived along the Pacific coast from roughly Icy Bay in the north to Chatham Sound in the south, or roughly throughout the Alaskan panhandle. This country, no more than 30 miles wide, but roughly 500 miles long, is marked by a profusion of fjords, inlets and bays, and islands, most of which are mountainous. The climate is marked by fog, rain, snow, and strong winds in fall and winter. Most Coastal Tlingits live in Alaska and in cities of the greater Northwest.

Interior Tlingits lived along the upper Taku River, although during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and in response both to the fur trade and the gold rush, most moved to the headwaters of the Yukon River. Many contemporary Interior Tlingit live in Teslin Village (Yukon Territory) and Atlin (British Columbia). Some also live in Whitehorse (Yukon) and Juneau (Alaska).

Population Total Tlingit population was at least 10,000 in 1740. Inland Tlingits probably never numbered more than 400. In the early 1990s there were roughly 14,000 Tlingits in the United States and 1,200 in Canada.

Language Tlingit is remotely related to Athapaskan languages.

Historical Information

History Humans have lived in Tlingit country for at least 10,000 years; continuous occupation of the region began around 5,000 years ago. People probably came from the south, with Tlingit culture perhaps having its origins near the mouths of the Nass and Skeena Rivers about 800 years ago. The earliest Tlingit villages had disappeared by historic times, however, and a new migration into the area began in the eighteenth century, as the Haida displaced southern Tlingit groups.

Russian explorers in 1741 were the first non-natives to enter the region. Spanish explorers heralded the period of regular interracial contact in 1775. The Russians had established a regular presence in 1790. They built a fort at Sitka in 1799 that fell to the Indians three years later. The Russians rebuilt in 1805, however, and made the fort the headquarters of the Russian-American Company from 1808 until 1867. Although the Tlingits maintained their independence during the Russian period, they did acquire tools and other items. Many fell to new diseases (a particularly severe smallpox outbreak occurred from 1835 to 1839), and some were converted to the Russian Orthodox Church.

In 1839, when the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired trading rights in southeastern Alaska from the Russian-American Company, the region saw an influx of European-manufactured goods. The advent of steel tools had a stimulating effect on traditional wood carving. During this time, the Tlingit successfully resisted British attempts to break their trade monopoly with the interior tribes. By the 1850s, Tlingits were trading as far south as Puget Sound and had regular access to alcohol and firearms from the Americans.

Tlingits protested the U.S. purchase of Alaska in 1867, arguing that if anyone were the rightful "owner" of Alaska, it was they and not the Russians. In any case, the soldiers, miners, and adventurers who arrived after the purchase severely mistreated and abused the Indians. For much of the last half of the nineteenth century, U.S. naval authorities persecuted shamans thought to be involved with witches. Although Tlingits owned southeast Alaska under aboriginal title, they were prevented from filing legal claims during, and thus profiting from, the great Juneau gold rush of 1880. The mines ultimately yielded hundreds of millions of dollars worth of gold, of which wealth the Tlingit saw little or none.

Commercial fishing and canning as well as tourism in the area became established in the 1870s and 1880s, providing jobs (albeit at wages lower than those earned by white workers) for the Indians. The Klondike gold rush of 1898-1899 brought more money and jobs to the region. Meanwhile, Christian missionaries, especially Presbyterians, waged an increasingly successful war against traditional Indian culture.

By 1900 many Tlingit had become acculturated. They had given up their subsistence economy and abandoned many small villages. Many worked in canneries in British Columbia or picked hops in Washington. Potlatches began to diminish in number and significance, and many ceremonial objects were sold to museums. Despite this level of acculturation, however, some mid-nineteenth century Tlingit villages continued to exist into the twentieth century.

In 1915, Alaska enfranchised all "civilized" natives, but severe economic and social discrimination continued, including a virtual apartheid system during the first half of the twentieth century. Some villages incorporated in the 1930s under the Indian Reorganization Act and acquired various industries. After World War II the issue of land led to the formation of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida, which in 1968 won a land claims settlement of $7.5 million ($0.43 an acre).

Despite Tlingit efforts, Alaska schools were not integrated until 1949. The Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB), founded in Sitka in 1912 by some Presbyterian Indians, was devoted to rapid acculturation; economic opportunity, including land rights; and the abolition of political discrimination. The Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS) was founded soon after. Both organizations reversed their stand against traditional practices in the late 1960s.

Religion Animals and even natural features had souls similar to those of people. Thus they were treated with respect, in part to win their help or to avoid their malice. Hunters engaged in ritual purification before the hunt, and during the hunt the hunter as well as his family back home engaged in certain formal rules of behavior.

Shamans were very powerful. Most were men. Shamans could cure, control weather, bring success in hunting, tell the future, and expose witches, but only if they were consulted in time and not impeded by another shaman. Their powers came from spirits that could be summoned by a special song. A shaman underwent regular periods of physical deprivation to keep spiritually pure. Neither he nor his wife could cut their hair.

Government The basic political units were matrilineal clans of two divisions, Raven and Eagle. Each clan was subdivided into lineages or house groups. Thus, the tribes, or groups, listed above lacked any overall political organization and were really local communities made up of representatives of several clans. All territory and property rights were held by the clans. Clan and lineage chiefs, or headmen, assigned their group’s resources, regulated subsistence activities, ordered the death of trespassers, and hosted memorial ceremonies.

Customs The two divisions served as opposites for marriage and ceremonial purposes. Some clans and lineages moved among neighboring groups such as the Haida, Tsimshian, and Eyak. A clan’s crest represented its totem, or the living things, heavenly bodies, physical features, and supernatural beings associated with it. Crests were displayed on house posts, totem poles, canoes, feast dishes, and other items. All present members of an opposite division received payment to view a crest, because in so doing they legitimated both the display and the crest’s associated privileges. All clan property could be bought and sold, given as gifts, or taken in war.

In general, spring brought hunting on the mainland, halibut fishing in deep waters, and shellfish and seaweed gathering. Seal hunting began in late spring, about the time of the first salmon runs. Summer activities generally included catching and curing salmon, berrying, and some sealing. Summer was also the time for wars and slave raids. Fall brought some sea otter hunting (land otter were never killed). In the late nineteenth century, fall was also the time for more salmon fishing and curing, potato harvesting, and hunting in the interior. Winter villages were established by November. Winter was the season for potlatches and trading.

Individuals as well as lineages were ranked, from nobility to commoners. Slaves were entirely outside the system. (Slaves were freed after the United States purchased Alaska and were brought into the social system on the lowest level.) Women had high status, probably because they controlled the food supply (not catching fish but the much harder and more laborious jobs of cutting, drying, smoking, and baling it). Any injury to someone in another clan required an indemnity. Clan disagreements were usually but not always settled peacefully. The three important feasts were the funeral feast, memorial potlatch feast, and childrens’ feast.

All babies were believed to be reincarnations of maternal relatives. At about age eight, a boy went to live with his maternal uncle, who saw that he toughened and purified himself and learned the traditions and responsibilities of his clan and lineage. Girls were confined in a dark room or cellar for up to two years (according to rank and wealth) at their first period, at which time they learned the traditions of their clan, performed certain rituals, and observed behavior restrictions. At the end of this time their ears were pierced, high-status families gave a potlatch, and girls were considered marriageable.

Only people of opposite divisions but similar clans and lineages could marry. Marriage formalities included mutual gift giving. Southerners erected tall mortuary totem poles near their houses. Death initiated a mourning period and several rituals, including singing and the funeral. Cremation occurred on the fourth day, except possibly longer for a chief. Widows observed particularly restrictive mourning rituals. A person’s slaves were sometimes killed. The evening after the cremation, mourners held a feast for their division opposites. Dead slaves were simply cast onto the beach. Burial was adopted in the late nineteenth century.

Dwellings Tlingits usually lived in one main (winter) village and perhaps one or more satellite villages. In the early nineteenth century, the former consisted of a row of rectangular, slightly excavated, gable-roofed planked houses facing the water. Each house could hold 40-50 people, including about six families and a few unmarried adults or slaves. Each family slept on partitioned wooden platforms that could be removed to make a larger ceremonial space.

Other features included a central smoke hole and a low, oval front doorway. The four main house posts were carved and painted in totemic or ancestral designs. Palisades often surrounded houses or whole villages. Other village structures included smokehouses, small houses for food and belongings, sweat houses, and menstrual huts.

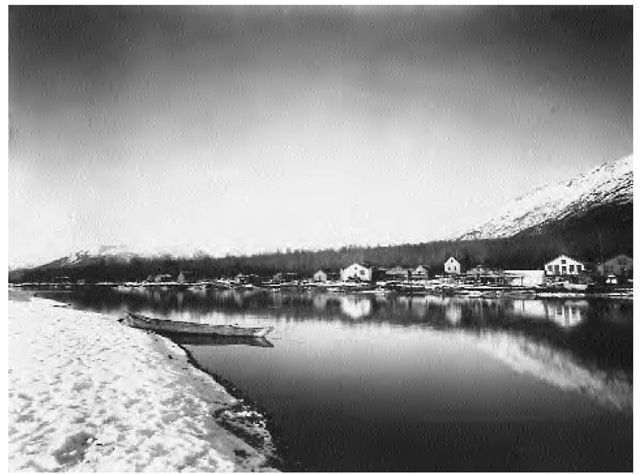

The Tlingit village of Klukwan in 1895. Tlingits usually lived in one main (winter) village and perhaps one or more satellite villages. In the early nineteeenth century the former consisted of a row of rectangular, slightly excavated, gable-roofed planked houses facing the water.

In the nineteenth century, Inland Tlingits lived in rectangular houses similar to those of the coastal people. They also built brush lean-tos that could shelter up to 10 or 15 people.

Diet Fish was the staple, especially all five species of salmon, as well as eulachon, halibut, and herring. Fish was boiled, baked, roasted, or dried and smoked for winter. Whole salmon might be frozen for winter use. Other important seafoods included shellfish, seaweed, seal, sea lion, sea otter, and porpoise.

The people also ate land mammals such as deer, bear, and mountain sheep and goat. Dogs assisted in the hunt. Inland Tlingit hunted caribou, moose, and some wood bison. Beaver were speared or netted under ice. Migrating waterfowl provided meat as well as feathers, eggs, and beaks. Some groups gathered a variety of berries, plus hemlock inner bark, roots (riceroot, fern), and shoots (salmonberries, cow parsnips). They began cultivating potatoes after the Russians introduced the food in the early nineteenth century.

People sucked cultivated tobacco mixed with other materials; they began smoking it when the Russians introduced leaf tobacco and pipes in the late eighteenth century.

Key Technology Salmon were caught in rectangular, wooden traps; trapped behind stone walls; or impaled on wooden stakes in low water. Other fishing equipment include hook and (gut) line, harpoons, and copper knives. Men hunted with spears, bow and arrow, a whip sling, and darts. Raw materials included horn (spoons, dishes, containers), wool (blankets), and wood (fire drill, watertight storage and boiling boxes). Tlingits began forging iron in the late eighteenth century, although some iron was acquired from intercontinental trade or drift wreckage in aboriginal times. Some foods were baked in earth ovens.

Trade Imports included walrus ivory from Bering Sea Eskimos, copper from interior tribes, dentalia shell from the south, Haida canoes, Tsimshian carvings, slaves, furs, skin garments decorated with porcupine quills, and various fish products. Exports included Chilkat blankets, seaweed, leaf tobacco, and fish oil. Intragroup trade was largely ceremonial in nature. When the whites came, Tlingits tried to monopolize that trade, even going so far as to travel over 300 miles to destroy a Hudson’s Bay Company post.

Inland Tlingit trade partners included the Tahltan, Kaska, Pelly River Athapaskan, and Tagish.

Notable Arts Tlingits excelled at wood carving, especially ceremonial partitions in house chiefs’ apartments, bentwood boxes, chests, and bowls, house posts (usually shells fronting the structural posts), masks, weapons and war regalia, and utilitarian and ceremonial items used by nobles.

Chilkat Tlingit blankets were the most intricate and sought-after textiles of the Northwest Coast. They were really ceremonial robes, and the ceremonies, in which myth was dramatized through dance, were fully as artistic as the crafts themselves.

Weaving of shirts, aprons, and leggings may have come originally from the Tsimshian. Rock art probably served functions similar to those of totems. Beadwork was of very high quality. Shamans used many art objects, including carved ivory and antler and bone amulets. Baskets were also an important Tlingit art.

Transportation Tlingits preferred the great Haida canoes that were purchased by wealthy Tlingit headmen. The most common type of canoe was of spruce, except in the south, where they used red cedar. Styles included ice-hunting canoes for sealing, forked-prow canoes, shallow river canoes, and small canoes with upturned ends for fishing and otter hunting. Some Inland Tlingits also used skin canoes, but most used rafts or small dugouts when they could not walk.

The Tlingits’ wood-carving expertise is exemplified in these totem poles in front of Chief Kadashan’s house in Wrangell, Alaska (1902).

Tlingits purchased Eyak and Athapaskan snowshoes. They carried burdens using skin packs with tumplines. Only a few coastal groups used Athapaskan-style sleds.

Dress In warm weather, women wore cedar-bark aprons, whereas men went naked. Blankets of woven cedar bark, mountain goat wool or dog hair, or tanned, sewn skins kept people warm in cold weather. Women wore waterproof basket caps and cedar bark ponchos in the rain. Conical twined spruce-root hats also served as prestigious crest objects.

Inland Tlingits wore pants with attached moccasins. Tailored shirts were made of caribou or moose skin. Winter clothing included goat wool pants, hooded sweaters made of caribou or hare skin, and fur robes.

War and Weapons War occurred between clans in different groups or tribes for reasons of plunder or, more often, revenge. Warfare included killing, torture, and the taking of women and children as slaves. Settlement involved the ceremonial kidnapping and ransom of high-ranking individuals, dancing, and feasting. Weapons included daggers, spears, war clubs, and bows and arrows. Fighters also wore hide and rod armor over moose-hide shirts as well as head and neck protection.

Chilkat Tlingit blankets, such as this one collected on Douglas Island off Alaska’s southwest coast in the late nineteenth century, were the most intricate and sought-after textiles of the Northwest Coast. They were really ceremonial robes, and the ceremonies, in which myth was dramatized through dance, were fully as artistic as the crafts themselves.

Although a considerable degree of intermarriage took place between the two groups, Interior Tlingits fought with Tahltans and Kaskas in the nineteenth century, mainly over trapping territory.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Many Tlingits live in their traditional villages, although many also live in urban centers in Alaska and the Northwest. In the Yukon, Tlingits form a part of the Carcross Tagish First Nation (Da Ka Nation Tribal Council). The Teslin Tlingit Council Band (part of the Da Ka Nation) controls three reserves on 187 hectares of land in the southwest part of Teslin. The 1993 population was 482 (119 houses). Elections have been mandatory (imposed by the Department of Indian Affairs) since the late 1940s. The clan leadership is composed of a chief and five counselors. Children attend band and provincial schools. Facilities on the reserves include two administration buildings, a longhouse, a clinic, a recreation center, and a drop-in center.

Economy At its founding in the early 1970s, Sealaska Corporation received 280,000 acres of timberland and $200 million. Each native village received surface land rights, and the corporation received subsurface rights to the same land. These corporations became active in logging, fishing, and land development.

Important economic activities of the Teslin Tlingit Council Band include a coin laundry. The band plans to organize a development corporation.

Legal Status The Sealaska Regional Corporation (Tlingit-Haida Central Council) is a federally recognized tribal entity. The council itself is composed of elected delegates from 14 communities in southeast Alaska and of representatives from other communities. The Hydaburg Cooperative Association is a federally recognized tribal entity.

Under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, 12 regional for-profit corporations (e.g., Sealaska Corporation) and roughly 200 village corporations were created and given nearly $1 billion and fee-simple title to 44 million acres in exchange for the extinction of aboriginal title to Alaska. The not-for-profit Sealaska Heritage Foundation supports a number of cultural activities.

Tlingit and Haida native villages include Angoon, Craig, Hoonah, Hydaburg, Juneau (Juneau Fishing Village), Kake, Klawok, Klukwan, Saxman, Sitka Village, and Yakutat.

The Teslin and Atlin Bands of Tlingit Indians are formally recognized by Canada.

Daily Life Most villages now have full electric service as well as amenities such as satellite television. Every village has a grade school, some have high schools, and all have at least one church. The traditional clan system still exists but has declined in importance. Relatively few people speak the Tlingit language, although it is now being taught in school. Most Tlingits are Christian. Urban Tlingits show a markedly greater level of assimilation than do those away from cities.

The ANB and the ANS now work toward cultural renewal. Some aspects of traditional culture and ceremonialism, such as potlatching (the memorial for the dead), singing and dancing, and crest arts (especially woodworking and carving) have undergone a revival in recent years.

Inland Tlingits became formally linked with the "outside" world when the Alaska Highway opened in the 1940s and again in the 1960s when radio and television became generally available. Most, especially the younger people, speak only English. There is still some traditional potlatching.