Powhatan, "falls in a current of water," part of a group of Algonquian speakers from North Carolina to New Jersey known as Renape ("human beings") or Lenape in the L dialect. The Powhatan tribes (Renape of Virginia) were culturally intermediate between the southeast and northeast regions.

Powhatan was also the main tribe and village of the roughly 30-tribe Powhatan Confederacy. Other prominent tribes included the Pamunkey, Chickahominy, and Mattaponi.

Location Powhatans traditionally lived in the Chesapeake Bay region of present-day Virginia. Today, most live in the Delaware Valley of Pennsylvania and New Jersey as well as in Oklahoma and Canada.

Population The confederacy numbered between 9,000 and 14,000 people in the early seventeenth century. That number had declined to about 500 in 1705. Today, about 600 people claim membership in the Powhatan-Renape Nation. There were roughly 450 Pamunkeys in the early 1990s.

Language Powhatan Indians spoke an Algonquian language.

Historical Information

History Aside from a short-lived Spanish mission in 1570, the British were the first European power in the region. By 1607, Chief Wahunsonacock (known to early British colonists as Powhatan) had expanded the confederacy by conquest from 6 or 8 tribes to more than 30. Shortly after the establishment of the Jamestown colony in 1607, the settlers began wide-scale cultivation of tobacco to sell in Europe. Because tobacco rapidly depletes the soil, the British constantly needed more land and did not shrink from obtaining it by fraud and trickery from the Indians.

According to legend, Pocahontas, daughter of Chief Wahunsonacock, intervened with her father to save the life of the leader of the Jamestown colonists, Captain John Smith. Smith was among a group captured in part because of Wahunsonacock’s anger at the colonists’ land grabbing and released after Wahunsonacock was crowned king in a British-style ceremony. Meanwhile, the colonists had captured Pocahontas and held her as surety against the other prisoners’ release. During her captivity she converted to Christianity and married a settler, inaugurating a period of peace between the two groups. Pocahontas traveled to Britain and died there in 1617, and Wahunsonacock died shortly thereafter.

In this nineteenth-century sketch, Pocahontas, the daughter of Chief Wahunsonacock, intervenes to save the life of the leader of the Jamestown colonists, Captain John Smith. Smith was among a group captured in part because of Wahunsonacock’s anger at the colonists’ land grabbing and released after the chief was crowned king in an English-style ceremony.

In 1622, the Powhatans determined to break the cycle of land thefts. Now led by Opechancanough, Wahunsonacock’s brother, they organized a revolt that killed almost 350 colonists and destroyed all settlements except Jamestown. In response, the colonial militia began a push to sweep the Indians farther inland. At one point, the British attacked a group of Indians who had come to attend a peace council. After years of bitter fighting, during which the Powhatans lost many people, peace was restored in 1636, but Opechancanough organized another revolt in 1644, at which time he may have been over 100 years old. Over 500 colonists died during this campaign. After Opechancanough was captured and shot in 1644, his people were forced out of Virginia or placed on reservations, and the confederacy came to an end.

Powhatan people were attacked by whites in 1675 after being falsely accused of depredations; the following year the whites massacred a large number of Powhatan men, women, and children living at a fort near Richmond. By this time, most Powhatan people and towns had disappeared. The people lost several of their reservations in the early eighteenth century. In 1722, Iroquois Indians agreed to stop attacking the Powhatans. Beginning in the 1770s, surviving Powhatans began migrating north to New Jersey, a movement that accelerated during and after the Civil War.

Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations of about 800 and 1,000 acres, respectively, remained in 1800. The reservations existed as a result of treaties signed with colonial governments. In 1831, most surviving Powhatans, many of whom had intermarried with African Americans, were chased away by whites in the aftermath of the Nat Turner slave rebellion. Few Powhatan Indians fought in the Civil War; those that did mainly did so on the Union side.

Following the Civil War, Virginia’s Indians fought successfully for a social—and legal—status higher than that of African Americans; the result was a three-way segregation system. This negotiation affected their legal identity as Indians. For instance, during World War I, Pamunkey and Mattaponi Indians protested the fact that they were drafted, since they were not citizens. The courts ruled in their favor. Having made their legal point, many proceeded to enlist.

Prior to World War II, many Pamunkeys continued to live by fishing, hunting, and trapping. Also during that time, attention paid to Virginia Indians by anthropologists stimulated a renewal of their ethnic identity and political organization, although this soon provoked a fierce white backlash. Powhatans began a community in the Philadelphia-Camden area, maintaining their native identity in part through a close network of families. They frequently intermarried with Nanticokes of Delaware and members of other tribes. Formal organization began in the 1930s, culminating in the emergence of the Powhatan Indians of the Delaware Valley in the 1960s and the Powhatan-Renape Nation in the 1970s.

Religion The chief deity was known as Okee. There were carved images of various kings and deities in the temples, as well as carved idols, dressed in various clothing and ornaments. There were at least one priest and temple in every village. Priests as well as conjurers were considered holy men. Chiefs had their own, private temples. Constructed like the houses, and partitioned with mats, these were used for worship as well as for burials of kings and for storehouses.

Priests made sacrifices of meat and tobacco at outdoor stone altars. Two or three children may have been sacrificed annually to propitiate the gods. There were regular communal ceremonies, including singing and dance, especially in times of triumph or crisis and at the harvest. Common people were thought to have no afterlife, but chiefs and priests were said to inhabit a western paradise until they were born again.

Government Each town, or kingdom, was led by a chief, or king. Sometimes, when kings controlled more than one town, a regent did the king’s bidding in his absence and paid him tribute. Chiefly descent was mainly matrilineal. Chiefs regularly poisoned their rivals.

The Powhatan Confederacy was an alliance of about 30 tribes (200 villages) at its peak in the early seventeenth century. Wahunsonacock, at least, was an absolute authority and inflicted torture or death at will. He also took a high tribute or tax from the people and was well guarded around the clock.

Customs Children were bathed daily in cold water for strengthening. Also for this purpose, various concoctions were rubbed into their skin. Furthermore, male children may have been beaten as part of a general toughening ceremony. Some of these young men may have been killed, perhaps as a sacrifice to the gods, while others were cast out into the wilderness for nine months, afterward to become priests or conjurers.

Men provided animal food, conducted ceremonies, fought, and probably made tools and weapons as well as houses and canoes. Women (except upper-class women) prepared food; grew and harvested crops; dressed skins; made mats, baskets, pots, and (perhaps) mortars; and carried burdens. As a rule, men and women did not eat together. Murder, certain thefts, and adultery were capital crimes. Goods and food were stored in holes in the ground. Doctors could cure certain wounds quite well. Sweating cured some sicknesses.

Corpses of commoners were wrapped in mats and buried in the ground, following which women wailed for a full day. Dead chiefs were ornamented with necklaces of beads and pearls. Baskets containing their valuables were placed at their feet. They were then wrapped in mats and placed on a scaffold. There was a period of public mourning, followed by a feast. Later, their bones were collected, hung from their houses, and buried with the remains of the houses when the latter fell apart or were destroyed.

Men had many wives; Wahunsonacock is said to have had over 100. Men announced their intentions by bringing the women a quantity of fresh food. After her family received presents and promises of more to come, the women was brought to the man for a small wedding ceremony, followed by a feast. Once she had a baby, the king’s wife was given a quantity of goods and dismissed, after which she was free to marry someone else; the child was taken from her and raised in the king’s household.

Dwellings Villages, often palisaded in the early seventeenth century, were usually located along a river. There were between 2 and about 100 houses and between 50 and 500 families per village/kingdom. Houses were constructed by bending and tying off saplings and then covering them with bark or woven mats. Roofs were rounded, with a smoke hole over the central fire. There were generally two mat doors that may have faced east. Beds, with skin covers, were placed along the walls.

Houses were generally built under trees. They may have had windows. Some elongated houses may have reached more than 100 feet in length, but most were much smaller. Several families lived in each house. There may also have been a combination raised storage/drying area under which men congregated.

Diet Fish and shellfish constituted a major part of the diet. Agriculture was somewhat less intensive than in other parts of the southeast. Women grew corn (three varieties), beans, and squash in fields of up to 200 acres. Corn was roasted or boiled and eaten fresh or pounded into cornmeal cakes. The people also gathered acorns and other nuts, fruits, and berries.

Some nuts and fruits were dried and stored for winter. A milky drink was made from walnuts. Men hunted deer, beaver, opossums, otters, squirrels, and turkeys, among other animals. Meat was broiled on a spit or boiled. The people also ate birds’ eggs.

Key Technology Men hunted using bows and arrows, spears, clubs, snares, and rings of fire. They speared and netted fish from their canoes; nets came from tree bark or grass woven with sinew. Digging sticks and hoes were the main farming tools. Women pounded grain in wooden mortars. Pottery, baskets, and mats were used for many purposes. Reeds and shells were fashioned into razors. Men carved pots and platters from wood. Musical instruments included rattles, drums, and reed flutes. Pipes were of both clay and stone. The people also built wooden bridges over creeks.

Trade Powhatans traded dried oysters for various furs and skins, deer fat cakes, vegetables, and possibly buffalo-horn spoons.

Notable Arts The main arts were basketry, beadwork, and pottery as well as ceremonial clothing woven from turkey feathers. Men carved religious images from wood.

Transportation Dugout canoes were up to 50 feet long.

Dress Women made the clothing, mostly from skins. Married women wore hairstyles that were different—longer in front—than those of unmarried women. They may have worn flowers and feathers in their hair. Men wore their hair long on the left side. They also wore earrings of bone and pearl as well as animal parts. Both sexes painted their bodies, particularly black, yellow, and red. The chief priests wore turkey feather cloaks and snake and weasel skin headdresses. Priests, but not common men, may have worn beards.

War and Weapons Weapons included tomahawks, bows and arrows, clubs, and shields. Priests had the final say about making war. The war chief and soldiers were generally appointed. The purpose of warfare was generally for revenge and to capture women and children; men were killed, often after torture. Women prepared the warriors’ hair with bear grease and special ornamentation, and they painted their faces. War parties left signs marking their presence and deeds.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Pamunkey State Reservation, located in King William County, Virginia, was established in 1658. It consists of about 1,200 acres and was home to about 30 families in the mid-1990s. The 1990 Indian population was 35. Other Pamunkeys live in nearby cities and towns and in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Government consists of an all-male seven-member tribal council, six non-Indian appointed trustees, and several committees. There is also a Pamunkey Indian Baptist Church governing board.

William Terrill Bradby, a Pamunkey Indian, at Pamunkey Reservation in 1899. The Pamunkey State Reservation, located in King William County, Virginia, was established in 1658. It consists of about 1,200 acres and was home to about 30 families in the mid-1990s.

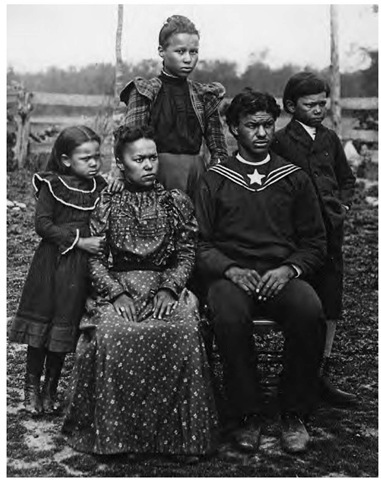

A turn-of-the-century Powhatan family from Virginia poses for a portrait in non-Indian dress. Prior to World War II, Powhatans began a community in the Philadelphia-Camden area, maintaining their native identity in part through a close network of families. They frequently intermarried with Nanticokes of Delaware and members of other tribes.

The Mattaponi State Reservation, King William County, Virginia, was established in 1658 and consists of 150 acres. There were 65 Indian residents in 1990.

A group of Chickahominy Indians lives along the Chickahominy River in New Kent and Charles Counties, Virginia.

The Powhatan-Renape Nation is a group of about 600 Chickahominys, Eastern Chickahominys, Mattaponis, Pamunkeys, Nansemonds, Nanticokes, Upper Mattaponis, and Rappahannocks living in the Delaware Valley of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The Nation acquired a 350-acre reservation (the Rankokus Reservation) in 1981 from the state of New Jersey.

Economy Pamunkeys and Powhatan-Renapes are fully integrated into the regional economy.

Legal Status The Powhatan-Renape Nation is a state-recognized, nonprofit tribal entity. The Pamunkey Nation is recognized by the state of Virginia. The Eastern Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, and the Nansemond Indian Tribal Association are state-recognized tribal entities. The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe is recognized by the state of Virginia and has petitioned for federal recognition. The United Rappahannock Tribe and the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Indians of New Jersey are state recognized and have petitioned for federal recognition.

Daily Life Facilities on the Powhatan-Renape Nation Reservation include an education center, conference center, art gallery, nature center, museum, and reconstructed traditional village. The people hold various crafts, language, and traditional culture classes. There is also an annual arts festival.

As mandated in the 1677 treaty on which their reservation is based, the Pamunkey continue every fall to deliver a quantity of fresh game to the Virginia legislature. This tribe won a land claim settlement in 1979; other cases are pending. The Pamunkey Indian museum, completed in 1979, forms the core of the people’s efforts to preserve their traditions. The Pamunkey Pottery Guild has helped revitalize pottery traditions and market the product.

Although many or most Powhatans resemble their non-native neighbors in looks and lifestyle, there is still an awareness of the key role of their Indian identity. The nature of this identity remains for many a matter of very personal negotiation. The Chickahominy hold a fall festival in September.