Owens Valley Paiute is the name given to a number of Paiute groups distinguished in part by their semisettled, cooperative lifestyle as well as their irrigation practices. They were largely responsible for bringing elements of California culture into the southern Great Basin. Non-natives formerly included them with the Monache or Mono Indians. "Paiute" may have meant "True Ute" or "Water Ute" and was applied only to the Southern Paiute until the 1850s. Their self-designation was Numa, or "People."

Location Traditionally, the groups now known as Owens Valley Paiute controlled the Owens River Valley, more than 80 miles long and an average of 7 miles wide. The fertile and well-watered region, east of the southern Sierra Nevada, contains a wealth of environmental diversity. Presently, Owens Valley Paiutes live on a number of their own reservations (see "Government/Reservations" under "Contemporary Information"), on other nearby reservations, and among the area’s general population.

Population In the early nineteenth century there were about 7,500 total Paiutes (perhaps 1,500-2,000 Owens Valley Paiutes). In the 1990s, about 6,300 Paiutes, including about 2,500 Owens Valley Paiutes, lived on reservations.

Language The Owens Valley Paiutes’ dialects of Mono are, with Northern Paiute, part of the Western Numic (Shoshonean) branch of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family.

Historical Information

History Owens Valley Paiutes first saw non-natives in the early nineteenth century (although they may have seen Spanish explorers earlier). These early explorers, trappers, and prospectors encountered Indians who were already irrigating wild crops.

Military and civil personnel surveyed the region in the late 1850s with an eye toward establishing a reservation for local Indians. The first non-Indian settlers arrived in 1861. These ranchers grew crops that fed nearby miners and other whites. As the white population increased, so did conflicts over water rights and irrigated lands. Whites cut down vital pinons for fuel. Hungry Indians stole cattle, and whites retaliated by killing Indians. As of early 1862, however, the Indians still controlled the Owens Valley, because they formed local military alliances.

Camp Independence was founded in July 1862 as a military outpost. Fighting continued well into 1863, until whites got the upper hand by pursuing a scorched earth policy. Many Indians surrendered but were back in the valley within a few years. By this time, however, whites had taken over most of their best lands, and a diminished Indian population was left to settle around towns, ranches, and mining camps, working mostly as laborers. Indians on newly reserved lands, increasingly including Western Shoshone families, worked mainly as small-scale farmers.

Indian schools opened in the late nineteenth century, although formal reservations were not established until the twentieth. Too small for ranches, the early reservations supported small-scale farming as the main economic activity. However, many Indians still lived on nonreservation lands and on other, non-Paiute reservations.

From the early twentieth century through the 1930s, the city of Los Angeles bought most of Owens Valley, primarily for water rights. This development destroyed the local economy, eliminating the low-level Indian jobs. The city also proposed new ways to dispossess and consolidate the remaining Indians at that time. Ultimately, most Indian people approved of the series of land exchanges (those at Fort Independence rejected the plans). During the 1940s, the federal government built new housing and sewer and irrigation systems on the new Indian lands.

Religion Religious observances centered on round dances and festivities associated with the fall harvest. Professional singers in elaborate dance regalia performed in a dance corral. The girls’ puberty ceremony was also important.

The cry was an annual Yuman-derived mourning ceremony for those who had died during the previous year. A ritual face washing (the first time since the death that the face was washed) marked the end of the official spousal year of mourning.

Male and female shamans were primarily doctors and religious leaders. Their power often came in a recurring dream. They cured by sucking, retrieving a wandering soul, or administering medicines. Disease was caused by soul loss, mishandling power, or sorcery. Special objects as well as songs, mandated by the power dream, helped them perform their tasks. They might acquire a good deal of clandestine political power by making headmen dependent on them.

Government Owens Valley Paiutes lived in semipermanent base camps, or hamlets, named for natural features. The camps were semipermanent in that (usually) the same families occupied them intermittently throughout the year and year to year. This level of social organization showed some similarities to California "tribelets." Within the camps families were completely independent. Families might share or coordinate in subsistence activities, but doing so was informal and unstructured.

Hamlets within a given area cooperated in intermarriage, irrigation, rabbit and deer drives, funerals, and the use of the sweat house. The headmen or chiefs directed these communal activities. Their other duties included conducting festivals and ceremonies, overseeing construction of the assembly lodge, and determining the death penalty for a shaman accused of witchcraft. The position was hereditary, usually in the male line.

Customs Although many people maintained the dams, an elected irrigator was responsible for watering a specific area. In summer, most families pursued hunting and gathering activities. They generally occupied their valley dwelling places in spring, the time of irrigation; fall, the time of social activities; and winter, unless the pine nut or Indian rice grass crops failed.

People held athletic contests and played a number of games, such as the hand game, shinny, the four-stick game, hoop and pole, and dice games.

Dwellings The Owens Valley Paiutes built several kinds of structures. The circular, semisubterranean sweat house served as an assembly house, a dormitory for young men, and a place for men to sweat. It was built, under sponsorship and supervision of local chief, of a central ridgepole supported by forked posts. A framework of poles was covered with earth and grass. Heat was by direct fire. The building also contained a central smoke hole, and the doorway faced east.

The winter family dwelling, 15 to 20 feet in diameter, was conical, semisubterranean, and built on a pole framework (no center ridgepole) covered with tule, grass, and sometimes earth. At mountain pine nut gathering winter camps, people built a wooden structure, perhaps with a gabled roof, consisting of poles of dead timber covered with bark slabs and boughs. In summer, ramadas of willow poles supporting a rectangular roof and covered with tule or brush, as well as semicircular brush windbreaks, served as the main living spaces.

Diet Diet also varied according to season and specific location. In general, the staple was pine nuts, harvested in autumn. Other important foods included acorns (prepared California-style); wild seeds, roots, and bulbs; berries; nuts; grasses (such as rice grass, ground into meal); cattails; and greens. Seeds were harvested in summer. Roots were either eaten raw or sand dried and stored. There was also some intentional irrigation of wild roots and seed-bearing plants.

In addition to the all-important plant resources, there was some fishing of suckers, minnows, and pupfish. The larvae and pupae of brine shrimp and fly were gathered, dried, shelled, and stored. People who had the assistance of a supernatural power hunted squirrels, quail, and other small game. The meat of small mammals was either pit roasted, boiled, or dried for storage. Rabbits were hunted in communal drives, deer in hunting teams. Caterpillar larvae were baked and sun dried.

Key Technology For irrigation, Owens Valley Paiutes used temporary dams and feeder streams of summer floodwaters. Their main tool was a long wooden water staff. They used nets to catch rabbits and fish. Fish were also speared or poisoned and often dried and stored for winter.

The Owens Valley Paiutes built several kinds of structures. Winter dwellings like this (early 1900s) were conical, semisubterranean, and built on a pole framework covered with tule, grass, and sometimes earth.

Hunting technology differed according to location, but usually featured a sinew-backed juniper bow, arrows, nets, snares, and deadfalls. Twined and coiled basketry included burden baskets with tumplines for distance (even transmountain) carrying and seed beaters. Fire was made with a drill, and smoldering, cigar-shaped fire matches were used to transport it. Roots were dug with mountain mahogany digging sticks. Nuts were ground and shelled with manos and metates or wood or stone mortars and stone pestles. Some women made pottery, from the mid-seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth century.

Trade The Monache, Miwok, Tubatulabal, and Yokuts of California were important trade, marriage, and ceremonial partners. Strung shell beads served as a medium of exchange. Acorns were usually imported, from the Monache, for example, in exchange for salt and pine nuts. The Owens Valley Paiute also traded shell money to the Western Shoshone for salt and rabbit-skin blankets.

Notable Arts Local rock art is at least several thousand years old. Art objects were also made from a variety of materials, including stone, wood, and clay.

Transportation Some groups plied the lakes and marshes with tule boats.

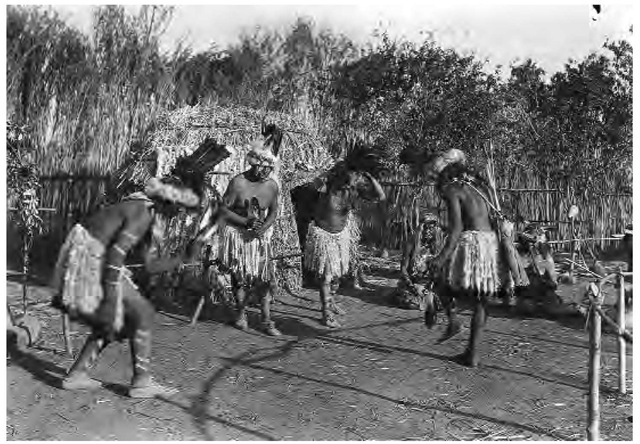

Dress Type and style of clothing varied according to location. In general, women wore tule or skin skirts, aprons, or dresses. Some women wore relatively large basket caps. Men favored a breechclout and perhaps a buckskin (or rabbit-skin or twined-sagebrush) shirt.

In winter, both sexes wore rabbit-skin or hide capes, hide or sagebrush-bark leggings, tule or hide moccasins, and fur caps. Other winter wear included rabbit-skin socks and twined sagebrush-bark or badger-skin boots. Both sexes wore sagebrush sandals and socks, headbands, and feather decorations in their hair. Men plucked their facial hair and eyebrows.

Men wove rabbit-skin blankets on a vertical frame. Shell necklaces and face and body paint were usually reserved for dances. Diapers and other such items were made of softened bark or cattail fluff.

War and Weapons The aboriginal Owens Valley Paiute seldom fought.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Significant numbers of Owens Valley Paiutes live on the following reservations:

Bishop Colony, Inyo County, California (1912; Owens Valley Paiute-Shoshone): 875 acres; 934 resident Indians (1990); 1,350 enrolled members (1991); five-member tribal council.

Fort Independence Reservation, Inyo County, California (1915; Owens Valley Paiute and Shoshone): 356 acres; 38 resident Indians (1990); 123 enrolled members (1991); three-member business council.

Lone Pine Reservation, Inyo County, California (1939; Owens Valley Paiute-Shoshone): 237 acres; 168 resident Indians (1990); 296 enrolled members (1991); five-member tribal council.

Big Pine Reservation, Inyo County, California (1939; Owens Valley Paiute and Shoshone): 279 acres; 331 resident Indians (1990); 413 enrolled members (1991); five-member tribal council.

Benton (Utu Utu Gwaitu) Paiute Reservation, Mono County, California (1915): 160 acres; 52 resident Indians (1990); 84 enrolled members (1991); five-member tribal council.

Each Owens Valley reservation is governed by a tribal council. Another administrative body, the Owens Valley Paiute-Shoshone Band of Indians (Big Pine, Lone Pine, Bishop, and Fort Independence) administers grant funds and valley-wide programs.

Economy The museum-cultural complex at Bishop provides some employment. Indians are also employed with the tribes and with a number of tribal businesses. Lone Pine, Fort Independence, and Benton have few current economic resources. There is some employment in local mines as well as some tourism.

Legal Status The following Paiute bands, locations, and peoples are federally recognized tribal entities:

Fort Independence Indian Community, Paiute-Shoshone Indians of the Bishop Community of the Bishop Colony, Paiute-Shoshone Indians of the Lone Pine Community, and Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute Tribe. The Washoe/Paiute of Antelope Valley, California, have petitioned for government recognition.

Daily Life The Bishop Colony maintains a culture center, a museum, and other facilities and programs. With the Owens Valley Paiute-Shoshone Band, they sponsor a summer powwow and rodeo. In the 1980s, elders persuaded the forest services not to apply pesticides against a Pandora moth infestation of nearby pinon pines; the moth’s larvae are still gathered and eaten, as are pine nuts and other traditional foods. Much of the Owens River and its watershed has been diverted to Los Angeles. Few people still speak Owens Valley Mono, although individual reservations sponsor cultural awareness and language programs. Other ongoing traditional activities include the cry ceremony, food gathering, and crafts. Outmigration remains a problem, as are poverty, poor health, and the continuing lack of job opportunities.

Paiute men of California’s Owens Valley wear ceremonial skirts of magpie feathers and twisted eagle down for a dance staged in 1932. Shell necklaces and face and body paint were usually reserved for dances.