Omaha ("0 ms ha) comes from Umon’hon, "those going against the current," a reference to the people’s migration down the Ohio River and then north on the Mississippi. They were closely related to the Ponca.

Location The Omaha inhabited the Ohio and Wabash Valleys in the fifteenth century. In the late eighteenth century they had migrated to northeast Nebraska. Today, most Omahas live along the Iowa-Nebraska border.

Population The late-eighteenth-century Omaha population was about 2,800 people. In the early 1990s, about 6,000 people were enrolled in the tribe.

Language Omaha is a member of the Dhegiha division of the Siouan language family.

Historical Information

History The group of Siouan people known as Omaha left the Wabash and Ohio River regions in the early sixteenth century. Shortly thereafter, they reached the Mississippi River and split into five separate tribes. The initial exodus was prompted in part by pressure from the Iroquois. Those who continued north along the Mississippi became known as Osage, Kaw, Ponca, and Omaha; the people who headed south were known as Quapaw.

The Omaha and Ponca, accompanied by the Skidi Pawnee, followed the Des Moines River to its headwaters and then traveled overland toward the Minnesota catlinite (pipestone) quarries, where they lived until the early to mid-seventeenth century. Then, driven west by the Dakota, they moved to near Lake Andes, South Dakota, where the Omaha and Ponca briefly separated.

Reunited, the two tribes traveled south along the Missouri to Nebraska, where they separated once again, probably along the Niobrara River, in the late seventeenth century. The Omaha settled on Bow Creek, in northeast Nebraska. After acquiring horses about 1730, the people began to assume many characteristics of typical Plains Indians.

During the eighteenth century, the Omaha visited French posts as far north as Lake Winnipeg. Well supplied with horses (from the Pawnee) and guns (from French traders), the Omaha were able to resist Dakota attacks, even acting as trade intermediaries with their enemies. In 1791-1792, the two warring groups signed a peace treaty.

By the early nineteenth century, heavy involvement in the non-native trade had altered Omaha material culture. A severe smallpox epidemic in 1802 reduced the population to around 300. In 1854 they were forced to cede their land and, the following year, to take up residence on a reservation. In 1865 the government created the Winnebago Reservation from the northern Omaha Reservation. In 1882 the reservation was allotted.

By 1900 most Omahas knew English, and many spoke it well. All lived in houses, and nearly all wore nontraditional clothing. Most children attended school, and a significant number of adults were succeeding as farmers or in other occupations in the nontraditional economy. Still, throughout the twentieth century, the Omaha fought further encroachments on the reservation and tribal sovereignty. Well-known twentieth-century Omahas include Francis La Flesche, who coauthored the classic ethnographic study The Omaha Tribe (1911); Susan La Flesche Picotte, the first Native American woman to earn a medical degree; and Thomas L. Sloane, mayor of Pender, Nebraska, and president of the Society of American Indians in the 1920s.

Religion Wakonda was the supreme life force, through which all things were related. People sought connection to the supernatural world through visions, which were usually requisite for membership in a secret society.

Two pipes featuring mallard heads attached to the stems were the tribe’s sacred objects. There were two religious organizations, the Shell and Pebble societies, which enacted a classic Woodlands ceremony of "shooting" a candidate with a shell and having him revived by the older members.

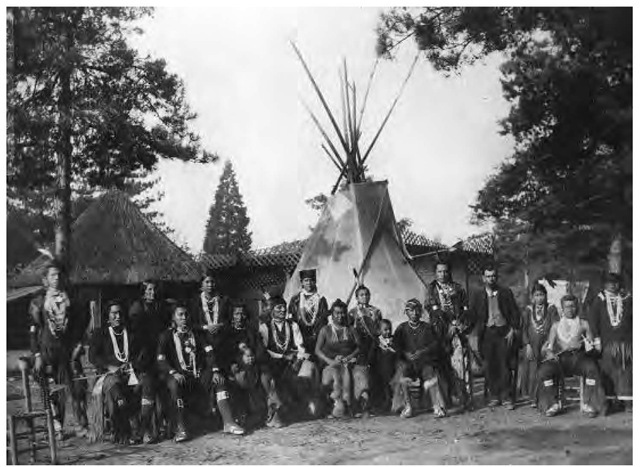

An Omaha group representing the North American Indians at the Colonial Exposition in Amsterdam in 1883. In the late eighteenth century the Omaha migrated to northeast Nebraska. Today, most Omahas live along the Iowa-Nebraska border.

Government Each of the two tribal divisions, sky people and earth people, were represented by a head chief and a sacred pipe, symbolized by a sacred pole. A tribal council of seven chiefs acted as arbitrators of disputes, with the ability to pronounce sentences that included banishment and the death penalty, and as representatives to other tribes. They also chose the buffalo hunt leader and a group of camp and hunt police.

Customs The two divisions were each composed of five patrilineal clans. There were numerous social and secret societies. Marriage took place outside the division. A man might have as many as three wives. The dead were placed in trees or scaffolds or were buried in a sitting position facing east. In the latter case, mounds of earth covered the grave.

Homicide was considered a crime against the wronged family; murderers were generally banished but allowed to return when the aggrieved family relented. The people played shinny and other games, including guessing/gambling games. During the communal buffalo hunt, tipis were arranged by clan in a circle. People gained status both in war and through their generosity.

Dwellings In villages located along streams, men and women built earth lodges similar to those of (and probably adopted from) the Arikara. About 40 feet in diameter, they were built of willow branches tied together with cords around a heavy wooden frame. The whole was covered with grass and sod. Skin curtains covered either side of the 6-to-10-foot entranceway. The fireplace was located in the middle, with an opening at the top for smoke.

In the nineteenth century, the Omaha built embankments around four feet high around their villages when they learned of an impending attack. Women also built skin tipis, which were mostly used during hunting trips—including the tribal spring and late-summer buffalo hunt—or in sheltered winter camps.

Diet Women grew corn, beans, and squash. Dried produce was stored in underground caches. After planting their crops, people abandoned the villages to hunt buffalo. The spring and summer buffalo hunts provided meat as well as hides for robes and tipis and many other material items. Men also hunted deer and small game. The people ate fish.

Key Technology Especially after the mid-eighteenth century, most material items were derived from buffalo parts. Hoes, for instance, came from buffalo shoulder blades. The Omaha made pottery until metal containers became available from non-Indian traders. They speared fish or shot them with tipless arrows. Nettle fibers were made into ropes. Bowls, mortars and pestles, and utensils were fashioned occasionally from horn but usually from wood. Hairbrushes were made of stiff grass.

Trade In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the Omaha traded regularly and often with French, British, and U.S. traders as well as local Indians.

Notable Arts Omaha artists made items using quills, paints, and beads. Black, red, and yellow were the traditional colors.

Transportation Horses were acquired about 1730. The people used hide bull-boats to cross bodies of water.

Dress Women dressed the skins for and made all clothing. They wore fringed tunics that left the arms free. Men wore leggings and breechclouts. Tattoos were used, especially ceremonially (such as a sun on the forehead and a star on the chest). Both sexes wore smoked skin moccasins as well as cold-weather gear such as robes, hats, and mittens.

War and Weapons Men’s warrior societies existed, although they were not as important as other religious and social organizations. Men fought with bow and arrow, clubs, spears, and hide shields. Enemies included the Dakota, at least from the eighteenth century on. The Skidi Pawnee were early (seventeenth-century) allies.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Omaha Reservation (Monona County, Iowa, and Burt, Cuming, and Thurston Counties, Nebraska), established in 1854, contains 26,792 acres, about 8,500 of which are tribally owned. There were 1,908 resident Indians in 1990. Authority is vested in an elected council of seven members plus a tribal chair.

Economy The Omaha tribal farm raises livestock. There is also income from the Chief Big Elk Park recreation area.

Legal Status The Omaha Tribe is a federally recognized tribal entity. The tribe gained civil and criminal jurisdiction over the reservation from Nebraska in 1970.

Daily Life Omaha children learn Omaha in schools, and roughly half of the people speak the language. Many former ceremonies have been lost. Some people are active in the Native American Church. Omahas also participate in traditional activities such as the hand game and the Gourd Dance. Traditional gift giving forms an important part of the annual tribal powwow. Omaha traditional music, especially warrior songs, has influenced the contemporary music of other Plains tribes.

In 1989, the tribe obtained the return of its sacred pole from Harvard’s Peabody Museum. Two years later the people effected the return, from the Museum of the American Indian in New York, of their sacred White Buffalo Hide. Plans for an interpretive center to house these and other items and exhibits are under way. Omahas have also worked for the return from museums and schools of human remains.