For people who have never lived there (and for some who have), the word "Arctic" conjures up a landscape almost incredibly forbidding. The Inuit, however, over the course of thousands of years, learned to live successfully in that cold, rugged country. Inuit (plural of Inuk) means "People" in the native language. In recent years, and especially in Canada and Greenland, it has replaced Eskimo, an Algonquian word meaning "eaters of raw meat" and one that many Inuit find offensive. The Unangan, or Aleut, are also generally considered to be Arctic, rather than Subarctic, residents.

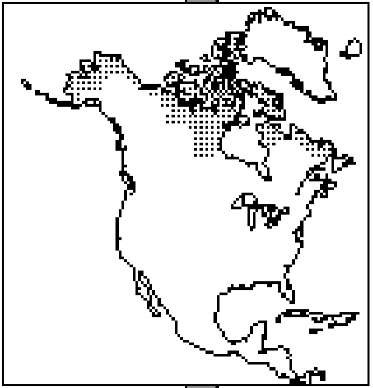

The Arctic is a remarkable region in several ways. It stretches 5,000 miles from Asia (Siberia) to Greenland and 1,800 miles from southeast Labrador to the Queen Elizabeth Islands. It encompasses well over 2,000 miles of the Alaska coast and is generally considered to include the 1,000-mile-long Aleutian Island chain. Another way to think of the vastness of the Arctic region is that it is roughly 12,000 miles (20,000 kilometers) from the eastern Aleutian Islands and along the coast of northern Alaska and Canada to Greenland. The total aboriginal population—including perhaps 15,000 Unangans, 31,000 Yup’iks, and 35,000 Inuits—was probably in the vicinity of 80,000 people. Four modern nations claim Arctic lands: Canada, Denmark, Russia, and the United States.

Arctic winters are long, dark, and extremely cold, except less cold right along the Pacific Ocean and adjacent waters. Although the interior may be colder in winter, fierce winds blow relentlessly along the coast. The flat tundra is covered with ice and snow in winter, but owing to poor drainage and the presence of permafrost it becomes boggy in summer, a perfect environment for mosquitoes, black flies, and other such insects. Although there are few or no trees in most of the Arctic, there are, during the brief summer, dwarf flowers, mosses, and lichens. As little as four inches of precipitation may fall in a year, except for Labrador and especially southwest Alaska. It is fortunate that ocean ice tends to lose its salinity after a year or so; otherwise finding fresh water would have been a serious problem for many Arctic residents.

Edward S. Curtis’s photo of an Inuit hut and family. In the summer, the Inuit constructed summer tents of seal or caribou skin over bone or wood frames.

All native Arctic people speak languages belonging to the same family, known as Eskimo-Aleut, or Eskaleut. Aleut is considered a separate language with two main dialects. The Eskimo language is made up of Inuit-Inupiaq (Eastern Eskimo), or Inuktitut, and Yup’ik. Yup’ik is divided into five branch languages and several dialects, whereas Inuktitut is broken merely into mutually intelligible dialects. The Inuit also maintained a nonverbal language based on body expression and other cues.

Some Arctic peoples were forced to deal with non-natives in the 1780s, whereas others did not experience direct contact until almost the twentieth century. The initial results of contact were mixed: They included disease epidemics, the breakdown of traditional structures and morality, and growing economic dependence as well as a new and acceptable religion and helpful trade goods. In many cases, native people continued to live in at least a semitraditional way until after World War II. Since then they have experienced many changes but not, as in the south, genocidal wars and the wholesale confiscation of their land.

Anthropologists remain uncertain whether the various native Arctic people came directly from Siberia or adapted to their environment from the Subarctic. Many believe that ancestors of the Inuit arrived in North America far later than did ancestral American Indians—perhaps only about 4,000 years ago—and in fact were preceded by at least 10,000 years by paleo-Indians. Along the Alaskan Peninsula and parts of the Aleutians, two cultures—Kodiak (circa 2500 B.C.E.) and Aleutian (circa 2000 B.C.E.)—continued approximately unchanged until the Russians arrived in the eighteenth century. Both were characterized by the use of poisoned lances for whaling, detachable barbed-head harpoons, an emphasis on clothing and personal decoration, and the development of woodworking, painting, and weaving.

Meanwhile, a hunting tradition known as Arctic Small Tool (Denbigh) arose around the Bering Sea from the Paleo-Arctic peoples of the rest of Alaska and northern Canada around 5,000 years ago. After about 1,000 years it had diffused throughout much of Alaska and Canada. These people made small flint blades, skin-covered boats, bows and arrows, needles, semiexcavated houses, and stone lamps. In the east, this complex was further refined into the somewhat more sea-oriented Dorset Tradition by about 1000 B.C.E. Dorset people also adapted well to snow and ice, possibly originating the snow house.

Again beginning in the Bering Sea area, the Norton culture materialized about 2,000 years ago. It in turn gave way to the Thule culture, which gradually overtook all other cultural traditions save the Aleutian by about the twelfth century. Thule people had dogs and sleds, umiaks and kayaks, the bow and arrow, and the harpoon thrower (atlatl), and they hunted whales. Through increased specialization and adaptation to local environments, this culture led directly to those found by non-natives.

With the possible exception of Native Alaskans, Arctic peoples were not organized into tribes. Instead, they saw themselves as members of groups that were tied to the land but whose definition nevertheless depended on perspective. These groups carried the suffix -miut, "people of." The smallest and most basic unit was the nuclear family. The extended family generally formed a household. Camps, or settlements,were seasonal constructions comprising one or more households. The larger of these groups might be considered bands.

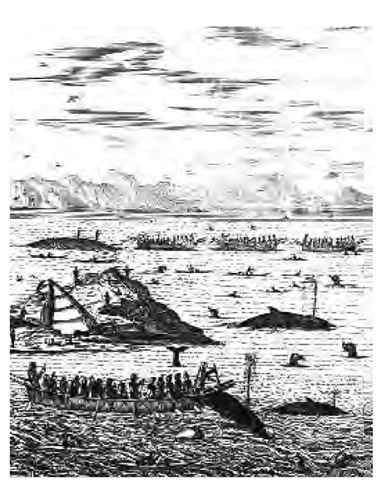

Whaling was a special occupation practiced mainly in northwest Alaska. The whaling umiaks were led by a captain and chief harpooner. This eighteenth-century drawing depicts whaling off the coast of Greenland.

Leadership was generally undeveloped in the Arctic. In certain temporary situations, such as whaling expeditions, strong leaders emerged, but there was little formal structure. Leaders were usually older, experienced men who might be heads of leading households and excellent hunters and who, in whaling cultures, probably owned an umiak. Authority was more formalized in southwest Alaska, owing partly to the influence of Northwest Coast cultures.

Hunting sea mammals—ringed and bearded seals, walrus, narwhal, and whales—was the main occupation of most Inuit men. Hunting walrus was considered inordinately dangerous, owing to the animals’ size and aggressive nature. (Polar bears presented the same problem and were taken, if at all, mainly for their hides.) Most men hunted seals from ice floes in winter. This was an extremely demanding task. Seals must come up for air, so men waited with their dogs and various equipment (see discussion of key technologies that applied to hunting) at breathing holes. In order to catch one seal, a man might have to guard a hole for hours, motionless in the dark and bitter cold. Breathing-hole sealing was done communally, so that a number of holes could be covered at once.

Whaling was a special occupation practiced mainly in northwest Alaska. The whaling umiaks were led by a captain and chief harpooner. Once the great animal was fatigued by the initial thrust and from the drags, it would slow down enough for other men to spear it to death. The whale was then either towed to shore or left to drift back. In the case of seals and whales, the kill was divided according to very precise and respected formulas.

In other seasons, a number of subsistence activities took place. Men stalked seals on the ice or harpooned them on open water from kayaks. Birds such as ptarmigan, ducks, and geese were taken, as were their eggs. In some areas, people gathered berries. Fishing was a three-season or in some areas a four-season activity.

Among the land animals, caribou were by far the most important source of food. Most groups took advantage of the great seasonal migrations, particularly those in late summer and fall. Men working together generally shot or speared the beasts from land or from kayaks as they crossed bodies of water or forced them, with corrals and/or stone cairns, into narrow places and shot them there. Other land animals used for meat and/or fur included musk ox, wolf, fox, wolverine, and squirrel.

In addition to food, caribou also provided the single most important source of raw material. From the caribou, and other animals as well, came clothing, shelter, bedding, boats, thread, and lines (sinew). The people made a variety of tools and weapons, such as harpoons, bow and arrow, needles, thimbles, knives, axes, adzes, drills, scrapers, and shovels, primarily from bone and antler. The defining women’s tools, reflecting their main activities, were the ivory or bone needle, the semilunar, sinew-backed knife, and the stone skin scraper.

People used a number of chipped stone (flint, slate, or quartz) items, such as points, blades, pots, and scrapers. Some copper was also used around Coronation Gulf. Many people depended on soapstone (pottery in southwest Alaska) oil- or blubber-burning lamps with moss wicks for heat and cooking. Wood, mainly driftwood, might provide boat and house frames, boxes, tool and weapon handles, and dishes. Depending on location, baleen could also be worked into boxes or other items. Other key technologies included movement indicators (for breathing-hole sealing), various types of harpoons (especially with detachable heads), throwers (atlatls), seal nets, bird bolas, three-pronged spears, fishhooks, stone fish weirs, and small animal traps and snares. Most people started a fire either by striking two pieces of pyrite or by friction generated with a thong drill.

Chipped stone work was well developed among the Native Arctic people, but they were particularly adept at carving figurines, amulets, toys, and other items out of bone, antler, and ivory. Tailored clothing was decorated with finely sewn furs. Some groups, mainly in Alaska, carved and painted wooden ceremonial and dance masks. Baskets were particularly fine among the Unangan, but people in southwest Alaska and in Labrador made them as well. In some areas, music and storytelling were considered high arts.

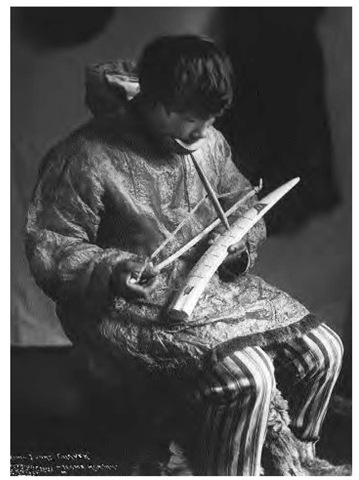

This ivory carver uses a bow to cause his wooden drill to burn into and penetrate a walrus tusk (1912).

Although they varied somewhat from place to place, kayaks were basically one-man, closed-deck hunting canoes. A wooden frame was lashed with sinew and covered with sewn seal or caribou skin. Men propelled them with double-bladed paddles, as shown in this 1906 photograph, and used them mainly for hunting.

Although kayaks varied somewhat from place to place, they were basically one-man, closed-deck hunting canoes. They were made of a wooden frame lashed with sinew and covered with sewn seal or caribou skin. Men propelled them with double-bladed paddles and used them mainly for hunting. Skin-covered umiaks were larger, open boats, used either for whale hunting or simply for transportation, depending on the region. In the latter case they were rowed or paddled by women. Sleds, pulled by dogs and/or people, were used for winter travel. These were built of a wood frame lashed together with rawhide. The wood, hide, or bone runners were often covered with moss and then ice to ensure a smooth ride.

Inuit built two basic types of winter houses, depending on location. Primarily in the central region, snow houses were the rule. Two men could build one in a hour or so. Snow blocks were cut,placed on a circle about 10 to 15 feet in diameter, stacked in an inward-moving spiral, and knocked into place. Small porches were generally used for storage. Women chinked the gaps with snow. People entered through a passageway built underground to trap the cold air and keep it out. A sheet of clear ice or gut served as a window. Benches and tables were made of snow. Snow platforms, covered with willow twigs or baleen and then thick, warm skins and furs, served as beds. Women tended the lamp, over which was placed a cooking pot or drying rack. Snow houses often were attached to one another in the interests of sociability and added warmth. They were also used temporarily by travelers and hunters in other parts of the Arctic.

The other major winter house type was the semiexcavated nonsnow dwelling. This square or oblong house was constructed of a wood or whale bone frame covered by sod and snow. As with the snow house, entrance was generally gained through an underground or tunnel-like passageway. In some areas people entered these houses through the roof. Other structures included the kashim, or men’s large ceremonial house, and summer tents of seal or caribou skin over bone or wood frames.

Dress, as might be imagined, was well constructed for warmth. Most clothing was made of tailored caribou skin, although polar bear, wolverine, squirrel, or even bird or fish skins were occasionally used by some groups. In general, people wore both inner and outer garments in winter, with the inner garment fur side in and the outer garment fur side out, although in summer only the inner garment was worn, fur side out. Outer shirts (parkas) were cut away at the sides and featured a long tail at the rear and a hood, which women wore extra large to shelter babies. Both sexes wore pants, stockings, insulated mittens, and sealskin boots or low shoes, depending on the season. Raincoats were carefully sewn of waterproof gut. Clothing was often decorated with colored furs or fringe. Items of personal adornment included labrets (lip plugs), ear pendants, nose rings, and tattoos.

An Arctic dwelling made of sod (right) and a storehouse (left) beside the Naknek River (1899). In this particular region of the Arctic, dwellings were mainly inhabited by related women and children. This photo also reveals the flatness of the tundra terrain. While there are few or no trees in the region, there are, during the brief summer, dwarf flowers, mosses, and lichens.

Although regional variations must be acknowledged, some common threads concerning religious belief among native Arctic people may be discerned. Most people believed that all things, animate and inanimate, had souls, or spirits. These beings varied in appearance. In order to maintain a positive and respectful relationship with them, particularly with the spirits of game animals, people observed any number of taboos or behavioral proscriptions and rules. Observing the taboos was considered an essential aspect of health maintenance. In order to enlist the aid of helpful spirits or to ward off bad spirits, people also used magic or wore amulets (identified with specific spirits and functions). The loss of an individual’s soul not only gave offense to other souls or spirits but might also cause illness or death.

Female and especially male shamans were in touch with and could control various beings of the spirit world. A long period of training was required before one could be considered a shaman. Shamans cured individual disease, and they saw to the overall health of the community, in part by ascertaining who broke which taboo when disaster befell the community. Performance was central to their method. They also exercised a degree of leadership in the community group. Their authority, however, was inspired more by fear than respect, as they were thought to be able to harm people through the agency of their supernatural powers.

In a more general sense, most native Arctic people recognized a dichotomy between the worlds of the land and the sea. There were various rules against using the same weapons to hunt land and sea animals, for example, and other taboos designed to maintain separation between the two realms. (This is one reason why the polar bear, which inhabited both land and sea, was considered so awesome.) There was also a general recognition (except in western Alaska and northwestern Hudson Bay) of an undersea female deity. Some western Alaska communities observed the Bladder and the Memorial Feasts. The Midwinter Feast was central to the ceremonial season in the central Arctic.

In terms of family and social customs, descent was generally bilateral. Kinship was of primary importance to these people, so much so that "strangers"—those who could not immediately document kin affiliations—were perceived as potentially hostile and might be summarily killed. Other groups of people subject to willful death were infants, especially females, and old people. Suicide was not uncommon, nor was cannibalism, but only in the most extreme cases of need. Prospective husbands often served a future bride’s parents for a period of time (bride service). Wife stealing, committed in the overall competition for supremacy, might end in death, as might other conflicts, although murders were subject to revenge. Corpses were generally wrapped in skins and left on the ground. In southwest Alaska and the Aleutians, mummification was also practiced. Pastimes included kickball, acrobatics, string games, and storytelling.

Traditional life began to change for most Arctic natives only with the introduction of fox fur trapping in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Trading posts sprang up in many native communities. Credit for food and other items extended in the fall was repaid with fox pelts in the spring. With more and more effort and resources going into trapping, and as opportunities for wage labor slowly increased, people began to drift away from their traditional lives. Residential areas around the posts grew in size, although most remained small until after World War II. Most included missionaries and, in Canada, a detachment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The former opened schools and clinics, and both worked to reduce violence among the Inuit.

Meanwhile, Russians had colonized southwestern Alaska and parts of the Aleutian Islands from the mid-eighteenth century on. The natives put up a fierce resistance to the Russians’ general brutality. After becoming wealthy from sea otters and seals, and defeating the people into the bargain, the Russians "sold" Alaska to the United States in 1867. By then, Yankee whalers were plying the north Alaska coast, bringing alcohol, disease, and trade items as well as some jobs and a measure of cosmopolitanism to the natives.

The near extinction of the whale population by the early twentieth century coincided with the beginning of fox trapping, commercial fishing and canning, and various gold rushes. These activities all brought severe disruption to Native Alaskans, along with some employment. At about the same time, the U.S. government required all native children to be removed from their families and educated at remote boarding schools. It also attempted to force the people to "settle down" by pressuring them to maintain domestic reindeer herds—not to farm, as was the case with Native Americans to the south.

At about the same time, the Canadian government, under the auspices of the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources (DNANR; 1954), assumed responsibility for comprehensive public assistance as well as compulsory education and health care. As part of these programs, it encouraged natives to settle down in permanent communities. In theory, settlements were self-governing, but decisions were subject to review by Canadian officials. School curricula were culturally and practically inappropriate. Local jobs, where they existed, were generally unskilled and poorly paid. Progress with diseases such as tuberculosis was gradually offset by the rise of substance abuse and other health problems caused by a less healthy diet as well as a general moral breakdown.

Since the 1960s, native people of the Arctic have become increasing active politically. In Canada, organizations like the Committee for Original People’s Entitlement (COPE, 1970) and the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (ITC, 1971) have taken the lead in advocating for land claims, appropriate resource management, language and educational rights, and other similar issues. In 1993, the Tungavik Federation of Nunavut (an outgrowth of the ITC) convinced the Canadian government to divide the Northwest Territories at the tree line and to establish in 1999 a new, mainly Inuit territory of roughly 350,000 square kilometers—roughly one-fifth of the land mass of Canada—to be known as Nunavut ("our land"). The settlement also includes over $1 billion in compensation as well as a strong Inuit role in decision making regarding land use and resource royalties. Other groups have claims pending as well.

A nineteenth-century woodcut depicts an Arctic version of a ball game using a stuffed sealskin.

Huge oil deposits were located on Alaska’s North Slope in the 1960s, and plans for an 800-mile pipeline were begun. People began to organize around this and other issues, such as their exclusion from discussions about Alaska’s native land claims as well as the low levels of opportunity for and the degree of poverty experienced by both rural and urban natives. In 1966, eight regional native organizations joined together to form the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) and proceeded to push a claim for almost 400 million acres of land.

Despite the growth of local cities and towns, most of the roughly 70,000 (1990) native Arctic people living on the Aleutian Islands and in Alaska (45,000) and Canada (25,000) still live in small communities in or near their traditional lands. Communities generally feature frame houses with all modern amenities. For reasons of survival as well as identity, many people still engage in subsistence activities, although guns, power boats, and snowmobiles have radically changed the hunting dynamic. Important economic activities in the far north also include commercial fishing, guiding, tourism, oil-related work, mining, construction, and government work and assistance. Various cooperative and traditionally organized businesses increase access to markets as well as goods and services. Arts and crafts, including sculpture, carvings, prints, and woven items, are a key part of the native economy.

In Canada, Inuktitut is spoken in all Inuit communities. Education is locally controlled, as it is in Alaska. Health problems, including substance abuse, death by accident and violence, malnutrition, and infectious disease, persist among Canadian Inuit. In general, Native Alaskans have access to good stores, transportation, and infrastructure. They face many of the same problems as do Canadian Inuit, however.

Building on a tradition of Inuit cooperation, and as part of a general pan-Inuit movement, the Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) held its first assembly in Barrow, Alaska, in June 1977. The ICC holds NGO (nongovernmental organization) status within the United Nations. It represents the interests of native Arctic people of Greenland (Denmark), Scandinavia, Canada, Alaska, and Russia. Major issues facing Arctic natives include land claims, sustainable economic development, environmental pollution, climate change, and sovereignty. Pollution—mainly from oil spillage, industrial chemicals such as PCBs, nuclear waste, and other sources—remains a big threat and a major issue in the Arctic. Despite the vast size of the Arctic, regional cooperation may offer the best hope for these people to make significant gains in the twin goals of political sovereignty and economic self-sufficiency.