Mohawk![]() , Algonquian for "eaters of men,"one of the five original tribes of the Iroquois League. The Mohawk self-designation was Kaniengehawa, "People of the Place of Flint." They were the Keepers of the Eastern Door of the Iroquois League. The name Iroquois ("real adders") comes from the French adaptation of the Algonquian name for these people. Their self-designation was Kanonsionni, "League of the United (Extended) Households." Iroquois today refer to themselves as Haudenosaunee, "People of the Longhouse."

, Algonquian for "eaters of men,"one of the five original tribes of the Iroquois League. The Mohawk self-designation was Kaniengehawa, "People of the Place of Flint." They were the Keepers of the Eastern Door of the Iroquois League. The name Iroquois ("real adders") comes from the French adaptation of the Algonquian name for these people. Their self-designation was Kanonsionni, "League of the United (Extended) Households." Iroquois today refer to themselves as Haudenosaunee, "People of the Longhouse."

Location The Mohawk were located mainly along the middle Mohawk River Valley but also north into the Adirondack Mountains and south nearly to Oneonta. At the height of their power, the Iroquois controlled land from the Hudson to the Illinois Rivers and the Ottawa to the Tennessee Rivers. Today, Mohawks live in southern Quebec and Ontario, Canada, and extreme northern New York.

Population There were perhaps 15,000-20,000 members of the Iroquois League around 1500 and roughly 4,000 Mohawks in the mid-seventeenth century. About 70,000 Iroquois Indians were living in the United States and Canada in the mid-1990s. Of these, about 28,000 were Mohawks: about 13,000 in Canada and 15,000 in the United States.

Language Mohawks spoke a Northern Iroquois dialect.

Historical Information

History The Iroquois began cultivating crops shortly after the first phase of their culture in New York was established around 800. Deganawida, a Huron prophet, and Hiawatha, a Mohawk shaman living among the Onondaga, founded the Iroquois League or Confederacy some time between 1450 and 1600. It originally consisted of five tribes: Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca; the Tuscarora joined in the early eighteenth century. The league’s purpose was to end centuries of debilitating intertribal war and work for the common good. Both Deganawida and Hiawatha may have been actual or mythological people.

Iroquois first met non-natives in the sixteenth century. There were sporadic Jesuit missions in Mohawk country throughout the mid-seventeenth century. During these and subsequent years, the people became heavily involved in the fur trade. Trading, fighting, and political intrigue characterized that period. Although they were good at playing the European powers off against each other, the Iroquois increasingly became British allies in trade and in the colonial wars and were instrumental in the ultimate British victory over the French.

Shortly after 1667, a year in which peace was concluded with the French, a group of Mohawk and Oneida Indians migrated north to La Prairie, a Jesuit mission on the south side of the St. Lawrence River. This group eventually settled south of Montreal at Sault Saint Louis, or Kahnnawake (Caughnawaga). Although they were heavily influenced by the French, most even adopting Catholicism, and tended to split their military allegiance between France and Britain, they remained part of the Iroquois League. Some of this group and other Iroquois eventually moved to Ohio, where they became known as the Seneca of Sandusky. They ultimately settled in Indian Territory (Oklahoma).

At about the same time, a group of Iroquois settled on the island of Montreal and became known as Iroquois of the Mountain. Like the people at Caughnawaga, they drew increasingly close to the French. The community moved in 1721 to the Lake of Two Mountains and was joined by other Indians at that time. This community later became the Oka reserve. Other Mohawks traveled to the far west as trappers and guides and merged with Indian tribes there.

Early in the eighteenth century, the first big push of non-native settlers drove into Mohawk country. Mohawks at that time had two principal settlements and were relatively prosperous from their fur trade activities. The establishment of St. Regis in the mid-eighteenth century by some Iroquois from Caughnawaga all but completed the migration to the St. Lawrence area. Most of these people joined the French in the French and Indian War, and their allegiance was split during the American Revolution.

The British victory in 1763 meant that the Iroquois no longer controlled the balance of power in the region. Despite the long-standing British alliance, some Indians joined anti-British rebellions as a defensive gesture. The confederacy split its allegiance in the Revolutionary War, with most Mohawks, at the urging of Theyendanegea, or Joseph Brant, siding with the British. This split resulted in the council fire’s being extinguished for the first time in roughly 200 years.

The British-educated Mohawk Joseph Brant proved an able military leader in the American Revolutionary War. Despite his leadership and that of others, however, the Mohawks suffered depredations throughout the war, and by war’s end their villages had been permanently destroyed. When the 1783 Treaty of Paris divided Indian land between Britain and the United States, British Canadian officials established the Six Nations Reserve for their loyal allies, to which most Mohawks repaired. Others went to a reserve at the Bay of Quinte, which later became Tyendinaga (Deseronto) Reserve.

The Iroquois council officially split into two parts during that time. One branch was located at the Six Nations Reserve and the other at Buffalo Creek. Gradually, the reservations as well as relations with the United States and Canada assumed more significance than intraconfederacy matters. In the 1840s, when the Buffalo Creek Reservation was sold, the fire there was rekindled at Onondaga.

In Canada, traditional structures were further weakened by the allotment of reservation lands in the 1840s; the requirement under Canadian law, from 1869 on, of patrilineal descent; and the transition of league councils and other political structures to a municipal government. In 1924, the Canadian government terminated confederacy rule entirely, mandating an (all male) elected system of government on the reserve.

The native economy gradually shifted from primarily hunting to farming, dependence on annuities received for the sale of land, and some wage labor. The people faced increasing pressure from non-natives to adopt Christianity and sell more land. The old religion declined during that time, although on some reservations the Handsome Lake religion grew in importance. During the nineteenth century, Mohawks worked as oarsmen with shipping companies, at one point leading an expedition up the Nile in Egypt. They also began working in construction during that period, particularly on high scaffolding.

At Akwesasne (see "Government/Reservations"), most people farmed, fished, and trapped during the nineteenth century. Almost all resident Indians were Catholic. Government was provided by three U.S.-appointed trustees and, in Canada, by a mandated elected council. With other members of the confederacy, Mohawks resisted the 1924 citizenship act, selective service, and all federal and state intrusions on their sovereignty.

Religion The Mohawk recognized Orenda as the supreme creator. Other animate and inanimate objects and natural forces were also considered to be of a spiritual nature. The Mohawk held important festivals to celebrate maple sap and strawberries as well as corn planting, ripening (Green Corn ceremony), and harvest. These festivals often included singing, male dancing, game playing, gambling, feasting, and food distribution.

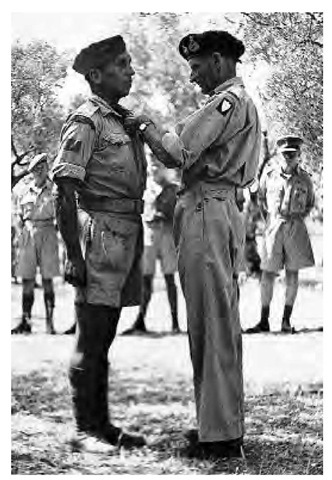

Private Huron Eldon Brant, a Mohawk, served with the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment during World War II. He is pictured here receiving the military medal for courage in action during the Sicilian campaign.

The eight-day new year’s festival may have been most important of all. Held in midwinter, it was a time to give thanks, to forget past wrongs, and to kindle new fires, with much attention paid to new and old dreams. A condolence ceremony had quasi-religious components. Medicine groups such as the False Face Society, whose members wore carved wooden masks, and the Medicine, Dark Dance, and Death Feast Societies (the last two controlled by women) also conducted ceremonies, since most illness was thought to be of supernatural origin.

In the early nineteenth century, many Iroquois embraced the teachings of Handsome Lake. This religion was born during the general religious ferment known as the Second Great Awakening and came directly out of the radical breakdown of Iroquois life. Beginning in 1799, the Seneca Handsome Lake spoke of Jesus and called upon Iroquois to give up alcohol and a host of negative behaviors, such as witchcraft and sexual promiscuity. He also exhorted them to maintain their traditional religious celebrations. A blend of traditional and Christian teachings, the Handsome Lake religion had the effect of facilitating the cultural transition occurring at the time.

Government The Iroquois League comprised 50 hereditary chiefs, or sachems, from the constituent tribes. Each position was named for the original holder and had specific responsibilities. Sachems were men, except where a woman acted as regent, but they were appointed by women. The Mohawk sent nine sachems (three from each clan) to meetings of the Iroquois Great Council, which met in the fall and for emergencies. Their symbol at this gathering was the shield.

Debates within the great council were a matter of strict clan, division, and tribal protocols, in a complex system of checks and balances. Politically, individual league members often pursued their own best interests while maintaining an essential solidarity with the other members. The creators of the U.S. government used the Iroquois League as a model of democracy.

Locally, the village structure was governed by a headman and a council of elders (clan chiefs, elders, wise men). Matters before the local councils were handled according to a definite protocol based on the clan and division memberships of the chiefs. Village chiefs were chosen from groups as small as a single household. Women nominated and recalled clan chiefs. Tribal chiefs represented the village and the nation at the general council of the league. The entire system was hierarchical and intertwined, from the family up to the great council. Decisions at all levels were reached by consensus.

There were also a number of nonhereditary chiefs ("pine tree" or "merit" chiefs), some of whom had no voting power. This may have been a postcontact phenomenon.

Customs The Mohawk recognized a dual division, each composed of three matrilineal, animal-named clans (Wolf, Bear, and Turtle). The clans in turn were composed of matrilineal lineages. Each owned a set number of personal names, some of which were linked with particular activities and responsibilities.

Women enjoyed a high degree of prestige, being largely equated with the "three sisters" (corn, beans, and squash), and they were in charge of most village activities, including marriage. Great intravillage lacrosse games included heavy gambling. Other games included snowsnake, or sliding a spear along a trench in the snow for distance. Food was shared so that everyone had roughly the same to eat.

Personal health and luck were maintained by performing various individual rituals, including singing and dancing, learned in dreams. Members of the False Face medicine society wore wooden masks carved from trees and used rattles and tobacco. Shamans also used up to 200 or more plant medicines to cure illness. People committed suicide on occasion for specific reasons (men who lost prestige; women who were abandoned; children who were treated harshly). Murder could be revenged or paid for with sufficient gifts.

Young men’s mothers arranged marriages with a prospective bride’s mother. Divorce was possible but not readily obtained because it was considered a discredit. The dead were buried in sitting position, with food and tools for use on the way to the land of the dead. A ceremony was held after ten days. The condolence ceremony mourned dead league chiefs and installed successors. A modified version also applied to common people.

Dwellings In the seventeenth century, Mohawks lived in three villages (Caughnawaga, Kanagaro, and Tionnontoguen) of 30 or more longhouses, each village with 500 or more people, as well as roughly five to eight smaller villages. The people built their villages near water and often on a hill after circa 1300. Some villages were palisaded. Other Iroquois villages had up to 150 longhouses and 1,000 or more people. Villages were moved about twice in a generation, when firewood and soil were exhausted.

Iroquois Indians built elm-bark longhouses, 50-100 feet long, depending on how many people lived there, from about the twelfth century on. They held around 2 or 3 but as many as 20 families, related maternally (lineage segments), as well as their dogs. There were smoke holes over each two-family fire. Beds were raised platforms; people slept on mats, their feet to the fire, covered by pelts. Upper platforms were used for food and gear storage. Roofs were shingled with elm bark. The people also built some single-family houses.

Diet Women grew corn, beans, squash, and gourds. Corn was the staple and was used in soups, stews, breads, and puddings. It was stored in bark-lined cellars. Women also gathered a variety of greens, nuts, seeds, roots, berries, fruits, and mushrooms. Tobacco was grown for ceremonial and social smoking.

After the harvest, men and some women took to the woods for several months to hunt and dry meat. Men hunted large game and trapped smaller game, mostly for the fur. Hunting was a source of potential prestige. They also caught waterfowl and other birds, and they fished. The people grew peaches, pears, and apples in orchards from the eighteenth century on.

Key Technology Iroquois used porcupine quills and wampum belts as a record of events. Wampum was also used as a gift connoting sincerity and, later, as trade money. These shell disks, strung or woven into belts, were probably a postcontact technological innovation.

Hunting equipment included snares, bow and arrow, stone knife, and bentwood pack frame. Fish were caught using traps, nets, bone hooks, and spears. Farming tools were made of stone, bone, wood (spades), and antler. Women wove corn-husk dolls, tobacco trays, mats, and baskets.

Other important material items included elm-bark containers, cordage from inner tree bark and fibers, and levers to move timbers. Men steamed wood or bent green wood to make many items, including lacrosse sticks.

Trade Mohawks obtained birch-bark products from the Huron. They imported copper and shells and exported carved wooden and stone pipes. They were extensively involved in the trade in beaver furs from the seventeenth century on.

Notable Arts Men carved wooden masks worn by the Society of Faces in their curing ceremonies. Women decorated clothing with dyed porcupine quills or moose-hair embroidery.

Transportation Unstable elm bark canoes were roughly 25 feet long. The people were also great runners and preferred to travel on land. Women used woven and decorated tumplines to support their burdens. They used snowshoes in winter.

Dress Women made most clothing from deerskins. Men wore shirts and short breechclouts and a tunic in cooler weather; women wore skirts. Both wore leggings, moccasins, and corn-husk slippers in summer. Robes were made of lighter or heavier skins or pelts, depending on the season. These were often painted. Clothing was decorated with feathers and porcupine quills. Both men and women tattooed their bodies extensively. Men often wore their hair in a roach, whereas women wore theirs in a single braid doubled up and fastened with a thong. Some men wore feather caps or, in winter, fur hoods.

War and Weapons Boys began developing war skills at a young age. Prestige and leadership were often gained through war, which was in many ways the most important activity. The title of Pine Tree Chief was a historical invention to honor especially brave warriors. Mohawks were known as particularly fierce fighters. Their enemies included Algonquins, Montagnais, Ojibwas, Crees, and tribes of the Abenaki Confederacy. In traditional warfare, at least among the Mohawk, large groups met face to face and fired a few arrows after a period of jeering, then engaged in another period of hand-to-hand combat using clubs and spears.

Weapons included the bow and arrow, ball-headed club, shield, rod armor, and guns after 1640. All aspects of warfare, from the initiation to the conclusion, were highly ritualized. War could be decided as a matter of policy or undertaken as a vendetta. Women had a large, sometimes decisive, say in the question of whether or not to fight. During war season, generally the fall, Iroquois war parties ranged up to 1,000 miles or more. Male prisoners were often forced to run the gauntlet: Those who made it through were adopted, but those who did not might be tortured by widows. Women and children prisoners were regularly adopted. Some captives were eaten.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Kahnawake/Caughnawaga (5,0599.17 hectares) and Doncaster (7,896.2 hectares) Reserves, Quebec, Canada, were established in 1667 as a Jesuit mission for mostly Oneida and Mohawk Indians. The mid-1990s population was about 6,500, of a total population of almost 8,000. The reserves are administered by a band council.

Oka/Kanesatake/Lake of Two Mountains, Quebec, Canada, established in 1676 by residents of Kahnawake, is populated mainly by Algonquians and several Iroquois tribes. It is roughly 10 square kilometers in size and is governed by a band council. The mid-1990s Mohawk population was about 1,800.

Gibson Reserve (Watha Mohawk Nation), Ontario, Canada, was established in 1881 at Georgian Bay by people from Oka/Kanesatake who resented resistance offered by the Sulpician Catholics to their cutting timber from the home reserve. The mid-1990s population was about 800.

St. Regis Reservation/Akwesasne Reserve, Franklin County, New York, and Quebec and Ontario, Canada, was formerly a mission established on the St. Lawrence River in the mid-eighteenth century for Mohawks and other groups. The resident Indian population in 1990 was 1,923, but the enrolled population approached 13,000. A tribal council provides local self-government. The 14,600 acres of this community straddle the international border.

Six Nations/Grand River, Ontario, Canada, was established in 1784. It is governed by both an elected and a hereditary council, although only the first is officially recognized by Canada.

Tyendinega Reserve (Deseronto), Hastings County, Ontario, Canada, is mainly a Mohawk reserve. The mid-1990s population was around 3,000.

Ganienkeh Reservation, Altoona, New York, had a mid-1990s population of about 300.

There is a small population of Mohawk high-steel workers in Brooklyn, New York.

In 1993, a small group from Akwesasne reestablished a Mohawk presence in New York’s Mohawk Valley, for the first time in 200 years. Known as Kanatsioharehe, the Mohawk population in the mid-1990s was about 50.

The Mohawk (Kahniakehaka) Nation does not recognize the U.S.-Canadian border, nor do they consider themselves U.S. or Canadian citizens. Their communities are governed under authority of the Grand Council of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

Economy At Kahnawake/Caughnawaga, most people engage in small-scale farming, high-steel work, factory work, and reservation government. There are also four schools on the reserve as well as a radio station, a newspaper, a hospital, and a credit union. At St. Regis/Akwesasne there is mainly high-steel work; small businesses, including bingo halls; and tribal government.

Legal Status The St. Regis Band of Mohawk Indians is a federally recognized tribal entity. The Canadian reserves listed under "Government/ Reservations" are provincially and federally recognized.

Daily Life Mohawks, particularly those from Kahnawake, have earned a first-rate reputation as high-steel workers throughout the United States since the late nineteenth century. People from Kahnawake have pursued self-determination particularly strongly. In 1990 there was a major incident, sparked by the expansion of a golf course, that resulted in an armed standoff involving local non-natives and the communities of Oka, Kahnawake, and Kanesatake. Akwesasne Mohawks have continued to battle the U.S. and Canadian governments over a number of issues. In 1968, by blocking the Cornwall International Bridge, they won concessions making it easier for them to cross the international border. The same year, a Mohawk school boycott brought attention to the failure of Indian education. In 1974, they and others established a territory called Ganienkeh on a parcel of disputed land. In 1977, New York established the Ganienkeh Reservation in Altoona.

The Akwesasne community has also been beset by fighting from within. In 1980, after the New York State Police averted a bloody showdown between traditionalists and "progressives," that body replaced the tribal police. In the late 1980s, violence was rampant over the issue of gambling. This situation had quieted but had not been resolved by the mid-1990s. Community leaders have had difficulty uniting around these and other divisive issues such as state sales and cigarette taxes, pollution, sovereignty, and land claims.

As a result of generations that have worked in high steel, Mohawk communities exist in some northeastern cities. Most of these people remain spiritually tied to their traditions, however, and frequently return to the reserves to participate in ceremonies, including Longhouse ceremonies, which have been active at least since the 1930s.

Akwesasne Mohawks publish an important journal, Akwesasne Notes. There is a museum and library at St. Regis. Many Mohawks still speak the native language, which remains the people’s official language. Akwesasne Mohawks face a barrage of administrative barriers, owing to their location in two U.S. counties and two Canadian provinces. Since the 1968 boycott, dropout rates have plunged from about 80 percent to about 10 percent. Major educational reforms have included the establishment of the Akwesasne Freedom School, the North American Indian Traveling College, language and culture courses, and an Indian library.

In general, traditional political and social (clan) structures remain intact. One major exception is caused by Canada’s requirement that band membership be reckoned patrilineally. The political structure of the Iroquois League continues to be a source of controversy for many Iroquois (Haudenosaunee). Some recognize two seats—at Onondaga and Six Nations—whereas others consider the government at Six Nations a reflection of or a corollary to the traditional seat at Onondaga. Important issues concerning the confederacy in the later twentieth century include Indian burial sites, sovereignty, gambling casinos, and land claims.

The Six Nations Reserve is still marked by the existence of "progressive" and "traditional" factions, with the former generally supporting the elected band council and following the Christian faith and the latter supporting the confederacy and the Longhouse religion. Traditional Iroquois Indians celebrate at least ten traditional or quasi-traditional events, including the midwinter, green corn, and strawberry ceremonies. Iroquois still observe condolence ceremonies as one way to hold the league together after roughly 500 years of existence. The code of Handsome Lake, as well as the Longhouse religion, based on traditional thanksgiving ceremonies, is alive on the Six Nations Reserve and other Iroquois communities. Roughly 15 percent of Canadian Mohawks speak their native language.